Journal of Theoretical & Computational Science

Open Access

ISSN: 2376-130X

ISSN: 2376-130X

Research Article - (2023)Volume 9, Issue 1

Hydrolysis of phosphate containing compounds is the key chemical reaction in biology that requires the breaking of O–H bond of water and P–O bond of the substrate. Latest computations reveal two proton transfer modes from the attacking water to the phosphate containing substrate during hydrolysis, i.e., a) direct proton transfer, and b) proton relay via a mediating base. We point out that the hydrolysis mechanisms can be classified based on the sequence in which O–H and P–O bonds break, the strength of the leaving nucleophile, and the modes of proton transfer. This results into a scheme that can be used to understand two specialized catalytic strategies utilized by the enzymes to hydrolyze the P–O–X (X=P, C) linkages: 1) Enzymes lower the nucleophile strength of the leaving group to facilitate the breaking of the scissile P–Ol bond and shift one formal negative charge from phosphate reaction center to the leaving nucleophile. 2) Many enzymes avoid direct proton transfer from the attacking water molecule to the phosphate reaction center. The direct proton transfer puts an excess proton (positive charge) on the phosphate reaction center that hinders the breaking of the P–Ol bond between phosphate and the leaving nucleophile. On the contrary, the indirect proton transfer from attacking water to the phosphate reaction center via helping water or an assisting catalytic base does not hinder the P–Ol bond breaking. These two strategies are present in many phosphate hydrolyzing enzymes.

Phosphate ester hydrolysis; Catalytic mechanism; Adenosine triphosphate; Biomolecular motors

containing compounds are the energy storehouses of life on earth. Life processes such as cytokinesis, organelle movement, muscle contraction, nucleic acid metabolism, signaling, protein synthesis, biochemical cycles and electron transport chain reactions depend on the hydrolysis of phosphate containing compounds [1-11]. The hydrolysis reaction in phosphate esters and phosphate anhydrides involves the breaking of very strong Oa–H bond of the attacking water molecule and the P–Ol bond of substrate (Oa and Ol denote attacking and leaving oxygen atoms, respectively) [12]. Phosphate esters and phosphate anhydrides undergo the hydrolysis of the P–O–C and P–O–P linkages, respectively (some phosphate- containing compounds also undergo the hydrolysis of a C–O–C linkage, e.g., 6-phosphogluconolactone in the second step of pentose phosphate pathway) [13]. P–O–C linkages in phosphate- esters are extremely high resistant to the spontaneous hydrolysis: The rate of hydrolysis (k) of phosphate esters is extremely low, e.g., 2 × 10−20 s1 for phosphate monoesters [14] and 10-15 s-1 for phosphate diesters [15]. Despite the wealth of structural X-ray, cryo-electron microscopy, kinetic [16], biochemical and mutagenesis experiments [17,18], the mechanism of hydrolysis of phosphate containing compounds can’t be solved using experimental techniques [19]. Indeed, an array of possible reaction mechanisms exists for the hydrolysis of phosphate containing compounds. Here computational quantum chemical studies have stepped in to study the hydrolysis mechanism of a wide range of phosphate esters (phosphate mono-, di- and triesters) as well as phosphate anhydrides (e.g., methyl pyrophosphate, and nucleoside triphosphates in vacuum, solution and protein environment using standard quantum mechanical or combined quantum mechanical/classical calculations that employ Empirical Valance Bond, SCC-DFTB, meta-dynamics, and Conjugate Peak Refinement approaches [4,19,20-44]. The aim of these computations is to understand the mechanism of the deceptively simple reaction of phosphate hydrolysis [45]. The non-enzymatic models of phosphate hydrolysis reactions provide appropriate mechanistic details in non-protein environment and their results are comparable to the experimental un-catalyzed reactions [12,20,46]. Computational studies of enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis reactions provide an insight into the strategies adapted by the proteins to effectively catalyze these substrates. Here, based on the most recent computational studies by us and others, we point out that modulating/lowering the strength of the P–Ol bond by lowering the nucleophile strength of the leaving nucleophile is one key strategy that has evolved in many enzymes and results in the breaking of the P–Ol bond before the breaking of Oa–H bond of the attacking water. Second key strategy observed in most enzymes is to avoid the direct proton transfer from the attacking water molecule to the phosphate reaction center. This second strategy also promotes the cleavage of P–Ol bond and lowers the barrier to the breaking of Oa–H bond.

Modes of proton transfer from the attacking water to substrate

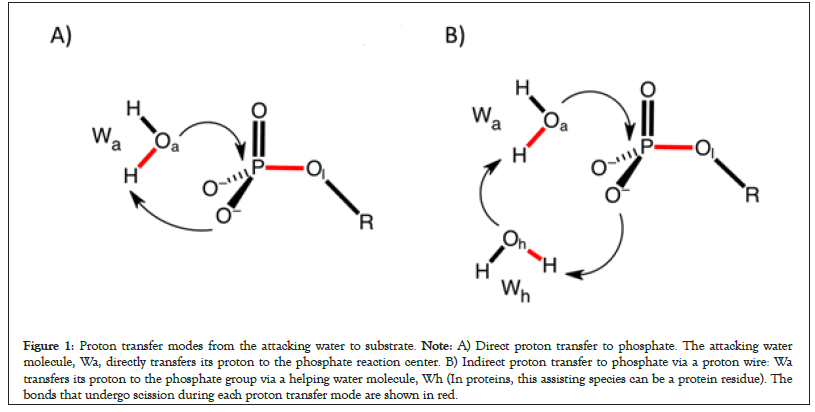

Two proton transfer modes from the attacking water molecule to the substrate have been reported for model reactions of phosphate hydrolysis in solutions (Figure 1). The direct proton transfer is head-on attack of the attacking water molecule (Wa) in which it directly transfers its proton to the phosphate (Figure 1A) [26,47]. In the proton relay mode, a helping water molecule or a protein residue mediates proton transfer from the attacking water to the phosphate (Figure 1B) [48]. Thus, the phosphate reaction center is the immediate proton acceptor in the direct proton transfer mode (Figure 1A) but proton transfer to the phosphate center is delayed in the proton relay mode (Figure 1B).

Figure 1: Proton transfer modes from the attacking water to substrate. Note: A) Direct proton transfer to phosphate. The attacking water molecule, Wa, directly transfers its proton to the phosphate reaction center. B) Indirect proton transfer to phosphate via a proton wire: Wa transfers its proton to the phosphate group via a helping water molecule, Wh (In proteins, this assisting species can be a protein residue). The bonds that undergo scission during each proton transfer mode are shown in red.

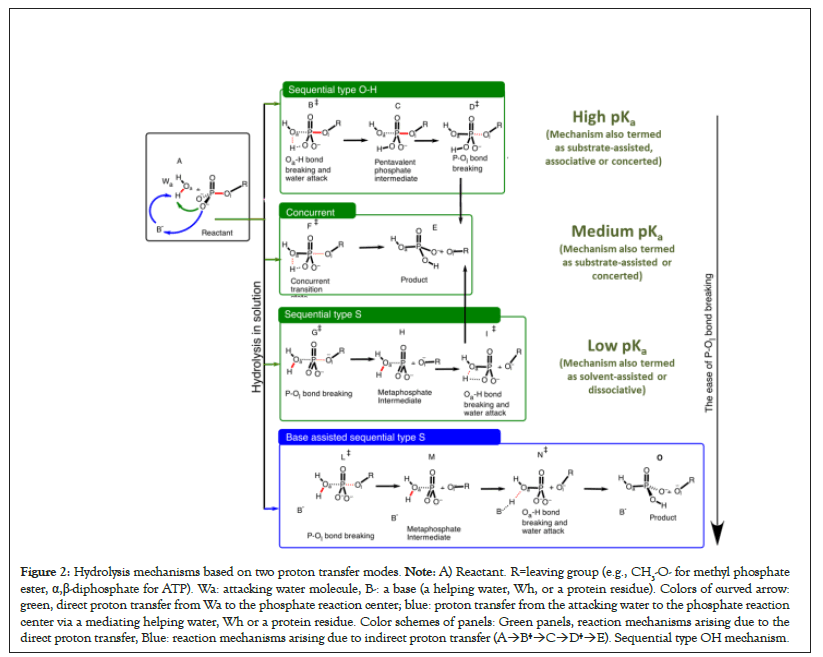

The Oa–H bond of Wa breaks before the P–Ol bond of the phosphate-containing compound. B‡ and D‡ correspond to the breaking of Oa–H and P–Ol bond, respectively (A→F‡→E). Concurrent mechanism. Transition state F‡ corresponds to the concurrent breaking of Oa–H and P–Ol bonds. A→G‡→H→I‡→E): Transition state for the sequential type S mechanism: The breaking of P–Ol bond (G‡) occurs before the breaking of Oa–H bond (I‡). A→J‡→K→L‡→M) Base assisted sequential type S mechanism. The attacking water molecule indirectly transfers its proton to the phosphate reaction center via a base, B-(a protein residue or a water molecule) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Hydrolysis mechanisms based on two proton transfer modes. Note: A) Reactant. R=leaving group (e.g., CH3-O- for methyl phosphate ester, α,β-diphosphate for ATP). Wa: attacking water molecule, B-: a base (a helping water, Wh, or a protein residue). Colors of curved arrow: green, direct proton transfer from Wa to the phosphate reaction center; blue: proton transfer from the attacking water to the phosphate reaction center via a mediating helping water, Wh or a protein residue. Color schemes of panels: Green panels, reaction mechanisms arising due to the direct proton transfer, Blue: reaction mechanisms arising due to indirect proton transfer (A→B‡→C→D‡→E). Sequential type OH mechanism.

Sequential versus concurrent mechanisms

We recently pointed out that the main contribution to the energy barrier during the hydrolysis reaction of phosphate esters and phosphate anhydrides arises due to the breaking of two strong bonds, i.e., the Oa–H bond of the attacking water and the P–Ol of the substrate [12,49,50]. We also proposed that the reaction mechanisms may be classified based on the sequence in which P–O and O–H bonds break during hydrolysis.

Here we reiterate the mechanistic scenarios arising due to the direct proton transfer mode, i.e., the mode in which the attacking water molecule directly transfers its proton to the phosphate reaction center (Figures 1A, also see green arrow in Figure 2A).

For this direct proton transfer, there can be situations in which P–Ol and Oa–H bonds break separately: If the Oa–H bond of the attacking water molecule breaks before the breaking of P–Ol bond of the substrate, the mechanism is referred to as sequential type OH mechanism A→B‡→C→D‡→E in Figure 2B, also see Figure 3 [51]. If the P–Ol bond of the phosphate-containing substrate breaks before the breaking of Oa–H bond, the mechanism is sequential type S mechanism (A→G‡→H→I‡→E) in Figure 2. There can be cases in which a single transition state corresponds to the breaking of P–Ol and Oa–H bonds (concurrent mechanism, Figure 2, A→F‡→E) [52]. Thus, the hydrolysis mechanism depends on the sequence in which Oa–H and P–Ol bonds break. Three cases mentioned in green panels in Figure 2 correspond to the direct proton transfer mode (Figure 1A) in which the phosphate reaction center of the substrate directly accepts proton from the attacking water.

Dependence of the phosphate ester hydrolysis on the nucleophile strength of the leaving group

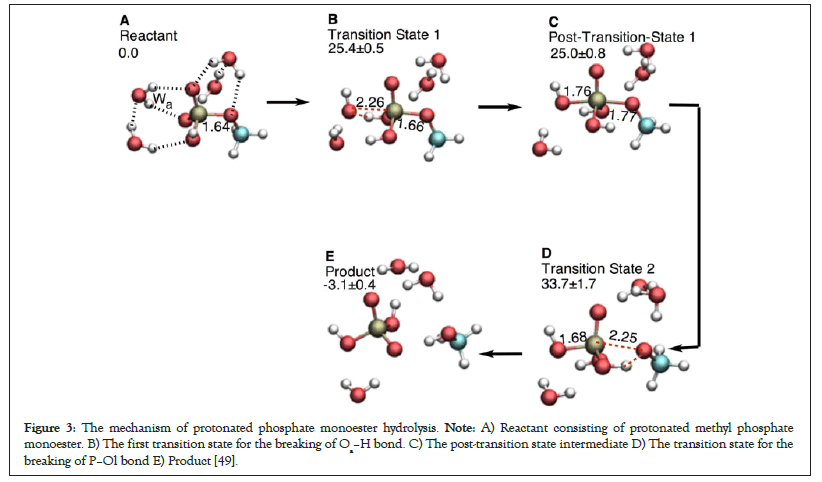

Kamerlin et al. greatly contributed in understanding the dependence of the hydrolysis reactions on the nucleophile strength of the leaving group in phosphate esters. It can be concluded from their work and from our calculations that the energetically favorable reaction mechanism in the direct proton transfer mode (Figures 1A and 2A) with the strong CH3-Oleaving nucleophile (pKa=15.5) is sequential type OH, i.e., the P–Ol bond breaking is delayed and the Oa–H bond breaks before the breaking of the P–Ol bond (see A→B‡→C→D‡→E, Figure 2, also see Figure 3) [53-55]. The energy profile of the sequential type OH mechanism has two saddle points corresponding to the breaking of Oa–H bond of the attacking water molecule before the breaking of P–Ol bond of the substrate [49].

Figure 3: The mechanism of protonated phosphate monoester hydrolysis. Note: A) Reactant consisting of protonated methyl phosphate monoester. B) The first transition state for the breaking of Oa–H bond. C) The post-transition state intermediate D) The transition state for the breaking of P–Ol bond E) Product [49].

There can be situations in which the two bond breaking events can’t be resolved in two separate transition states and the corresponding energy barrier involves contributions from both bond-breaking events (Figure 2, A→F‡→E). This concurrent mechanism has been observed for the leaving groups with moderate or low pKa (e.g., 3,5-nitrophenyl: pKa=6.68, 4-nitrophenyl: pKa=7.14 [55]), a single transition state is isolatable.

For even better leaving groups like CH3COO-, sequential type S mechanism (A→G‡→H→I‡→E in Figure 2) in which P–O bond breaks before the breaking of OH bond. This mechanism is energetically much more favorable over the concurrent mechanism for the CH3COO- leaving nucleophile [53].

Taking proton transfer by the proton relay into account

Taking into account the second proton transfer mode i.e., the proton relay or the indirect proton transfer in which the direct proton acceptor is not the substrate itself, but a base located in the vicinity of the attacking water (Figure 1B, respectively) one additional mechanism, i.e., base-assisted sequential mechanism type S mechanism (A→J‡→K→L‡→M, Figure 2) emerges. In neutral solution, this base is usually a water molecule [27,28]. In protein environment, this base can potentially be either a helping water molecule (Wh), or a protein residue or both [29,32,43,56- 59]. Enzymes also use some additional strategies to lower the energy barrier. The base-assisted sequential type S mechanism can have at least three bond breaking events.

The direction of charge shift in phosphate hydrolysis reactions

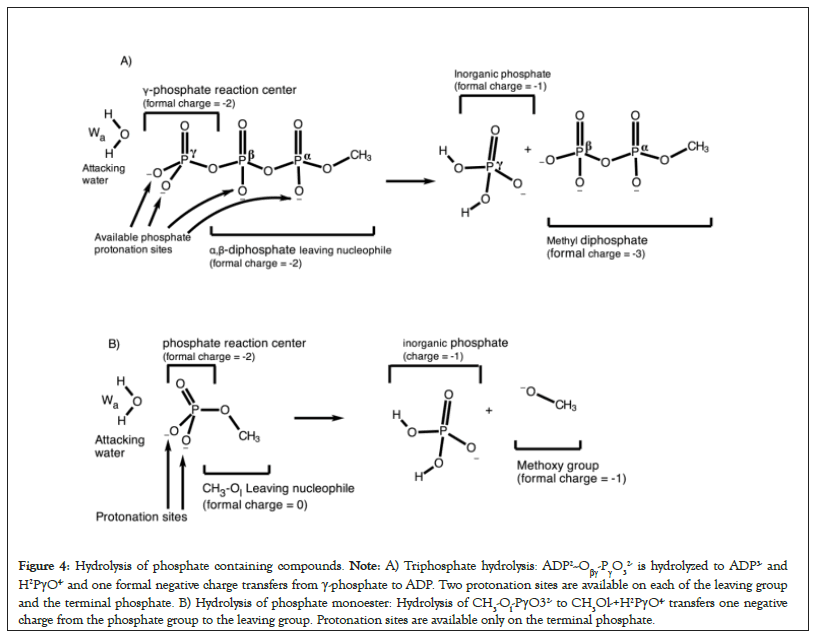

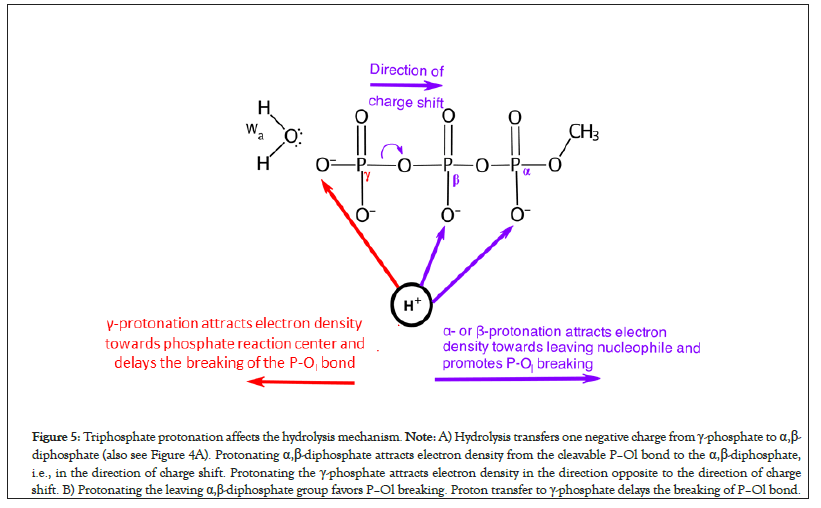

In the pre-hydrolysis state of ATP, two formal negative charges are present on each of the γ-phosphate and the leaving α,β- diphosphate nucleophile (Figures 4A and 4B). During the net ATP hydrolysis reaction (H2O+ADP2-Oβγ-PγO32- → ADP3- + H2PγO4-), the breaking of Pγ-Oβγ bond shifts one formal negative charge from the γ-phosphate to the ADP (see the direction of charge shift in Figure 5) [60]. Consequently, one formal negative charge is present on the γ-phosphate and three formal negative charges are present on ADP in the post-hydrolysis product (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Hydrolysis of phosphate containing compounds. Note: A) Triphosphate hydrolysis: ADP2--Oβγ-PγO32- is hydrolyzed to ADP3- and H2PγO4- and one formal negative charge transfers from γ-phosphate to ADP. Two protonation sites are available on each of the leaving group and the terminal phosphate. B) Hydrolysis of phosphate monoester: Hydrolysis of CH3-Ol-PγO32- to CH3Ol-+H2PγO4- transfers one negative charge from the phosphate group to the leaving group. Protonation sites are available only on the terminal phosphate.

Figure 5: Triphosphate protonation affects the hydrolysis mechanism. Note: A) Hydrolysis transfers one negative charge from γ-phosphate to α,β- diphosphate (also see Figure 4A). Protonating α,β-diphosphate attracts electron density from the cleavable P–Ol bond to the α,β-diphosphate, i.e., in the direction of charge shift. Protonating the γ-phosphate attracts electron density in the direction opposite to the direction of charge shift. B) Protonating the leaving α,β-diphosphate group favors P–Ol breaking. Proton transfer to γ-phosphate delays the breaking of P–Ol bond.

In the pre-hydrolysis state of phosphate monoesters, the phosphate group occupies two formal negative charges. The breaking of P– Ol bond shifts one negative charge from the phosphate reaction center to the methoxy group during the net hydrolysis reaction (H2O+CH3-Ol-PγO32- →CH3Ol-+H2PγO4, Figure 4B). Thus, the post-hydrolysis pre-product has one formal negative charge on the phosphate as well as on the leaving methoxy group. This directionality of charge shift from the phosphate reaction center to the leaving group in both reactions is crucial (Figure 4). In the next sections, we show that any protonation event of the substrate or its electrostatic interaction with the binding site that favors this charge shift by attracting electron density in the direction of charge transfer promotes sequential type S mechanism (e.g., see the effect of protonation of α or β-phosphate groups on the mechanism, Figure 5). On the contrary, any protonation event that hinders or opposes this charge shift from the reaction center to the leaving nucleophile, e.g., by attracting electrons in the direction opposite to the direction of the charge shift transforms the mechanism from sequential type S → concurrent → sequential type OH.

Protonation of phosphate reaction center delays P–Ol bond cleavage

When γ-phosphate is protonated in model reactions of triphosphate hydrolysis but alpha- and beta-phosphates are not, sequential type S mechanism could not be obtained [49]. This is because when γ-site is protonated, the extra positive charge on γ-site in ADP2--Oβγ-PγO3H- attracts electron density towards the phosphate reaction center, i.e., in the direction opposite to the direction of the desired charge shift (Figure 5). Thus, adding protons to the γ-phosphate in ATP delays the onset of P–Ol bond breaking during hydrolysis (Figure 5).

Similar trend can be observed in the hydrolysis of methyl phosphate ester (Figure 3). The CH3O- leaving group in methyl phosphate ester is a strong leaving nucleophile (pKa=15.5). The hydrolysis mechanism of deprotonated methyl phosphate ester is inclined towards sequential type Oa–H (Figure 2) [49,54]. Protonating the phosphate reaction center in methyl phosphate increases the strength of the P–Ol bond. The P–Ol bond distances of the reactant, transition state 1, post transition state 1, and transition state 2 in protonated case (Figure 3) are smaller than those in the deprotonated phosphate monoesters (Table 1). This is because the phosphate protonation attracts electron density towards the protonated terminal phosphate thus hindering the departure of the leaving group. The energy difference in going from the post-hydrolysis intermediate to the transition state for P–Ol bond breaking also marginally increases from 7.0 (compare 33.8 ± 0.7 kcal mol-1 with 40.8 ± 1.9 kcal mol-1) in deprotonated case to 8.7 (compare 25.0 ± 0.8 kcal mol-1 with 33.7 ± 1.7 kcal mol-1) in protonated case (Table 1). Recent studies in Ras protein are suggestive that the γ-phosphate in GTP is not protonated [61].

| Structure | P–Ol distance | Relative energies (ΔE) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protonated | Deprotonated | Protonated | Deprotonated | |

| Reactant | 1.64 | 1.71 | 0 | 0 |

| Transition state 1 | 1.66 | 1.78 | 25.4 ± 0.5 | 33.6 ± 0.8 |

| (O–H breaking) | ||||

| Post-transition state 1 | 1.77 | 1.8 | 25.0 ± 0.8 | 33.8 ± 0.7 |

| Transition state 2 | 2.25 | 2.52 | 33.7 ± 1.7 | 40.8 ± 1.9 |

| (P–O breaking) | ||||

| Product | - | - | -3.1 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.7 |

Table 1: P–Ol distance and relative energies of stationary points during the hydrolysis of protonated and deprotonated phosphate monoesters.

α and β-diphosphate protonation of ATP promotes P–Ol bond cleavage

Computations reveal that protonating α- or β-phosphate groups of triphosphate facilitates the breaking of P–Ol bond before the breaking of Oa–H bond of water (sequential type S mechanism, Figure 2). This is because additional protons on the leaving α,β- diphosphate decreases its nucleophile strength by attracting electron density away from the P–Ol bond towards the leaving group (in the direction of the charge shift). This reduces the strength of the P–Ol bond and results in facile departure of the leaving nucleophile by breaking the P–Ol bond of ATP before the Oa–H bond of water molecule (sequential type S mechanism, Figure 2).

Indirect proton transfer from attacking water to the terminal phosphate promotes P–Ol bond cleavage

Reactions that employ an indirect proton transfer from the attacking water to the phosphate reaction center via a helping water molecule or a catalytic base are biased towards a sequential type S mechanism (i.e., P–Ol bond breaks first), for instance [27]. Furthermore, when attacking water molecule transfers its proton to the γ-phosphate using direct transfer mode, the sequential type OH mechanism or a concurrent mechanism is energetically favorable (i.e., P–Ol bond breaking is delayed) [49]. Since, the direct proton transfer from the attacking water to the γ-phosphate in the hydrolysis of ADP2--Oβγ-PγO32- also puts an excess proton on the γ-phosphate, this extra proton increases partial positive charge on the phosphorus center thus strengthens the P–Ol bond by attracting electron density towards the γ-phosphate (in the direction opposite to the charge transfer) and thus delays the onset of cleavage of the P–Ol bond. In addition, stereo electronic factors are also important: The four-centered transition state formed in the direct proton transfer may not be ideal energetically as compared to the six-centered transition state formed as a result of proton relay [32,62-66].

Lowering the nucleophile strength in phosphate monoesters promotes P–Ol bond cleavage

The sequential type OH mechanism in which Oa–H bond breaks before the breaking of the P–Ol bond during the hydrolysis of methyl phosphate ester (Figures 3 and 6) is energetically much more favorable [54]. This is because the departure of the strong leaving CH3-Ol-nucleophile (or a poor leaving group) is difficult therefore Oa–H bond breaks slightly before the breaking of the P–Ol bond [49]. For the triphosphate hydrolysis in solution, the leaving group phosphates can be protonated to decrease its nucleophile strength. The leaving nucleophile in phosphate esters has no negatively charged phosphate moiety that can be protonated (Figure 4B). Therefore, it is not possible to use phosphate protonation to study the effect of nucleophile strength in phosphate monoester. However, the effect can be studied by directly substituting the strong leaving nucleophile with a week leaving nucleophile in phosphate monoester. Kamerlin et al. studied the hydrolysis of phosphate monosters by replacing the strong CH3-Ol group with relatively weaker nucleophiles [56]. Replacing the strongly nucleophile methyl group by a weak nucleophile changed the mechanism from sequential type O–H (A→B‡→C→D‡→E in Figure 2, nucleophile=CH3O-, pKa=15.5) to concurrent (A→F‡→E, nucleophile=3,5- nitrophenyl, pKa=6.68). Similar effect has been found in alkaline phosphatases. Substrates with a weak leaving nucleophile have larger P–Ol distances whereas substrates with a strong leaving nucleophile have smaller P–Ol distances [67,68]. Changing the nucleophile strength in non-enzymatic systems with different central electrophilic atoms (including phosphorus) and different leaving groups has been recently reviewed [69].

Strategies employed by proteins to hydrolyze phosphate- containing compounds

Enzymes employ specific strategies to reduce the rate to the hydrolysis reaction of phosphate containing compounds (for instance the rate of hydrolysis of phosphate anhydride P–O–P linkage of ATP in the myosin motor is 3.2 × 10-5 s-1) [70,71]. Many recent computational quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical studies that employ very sophisticated quantum mechanical methods to study the hydrolysis mechanism in several proteins show a base assisted sequential type S mechanism in which P–Ol bond breaks before the breaking of the Oa–H bond. The examples include ATP hydrolysis in myosin, kinesin, and F1-ATPase [33,52,72]. This protein-catalyzed sequential type S mechanism employs two main strategies:

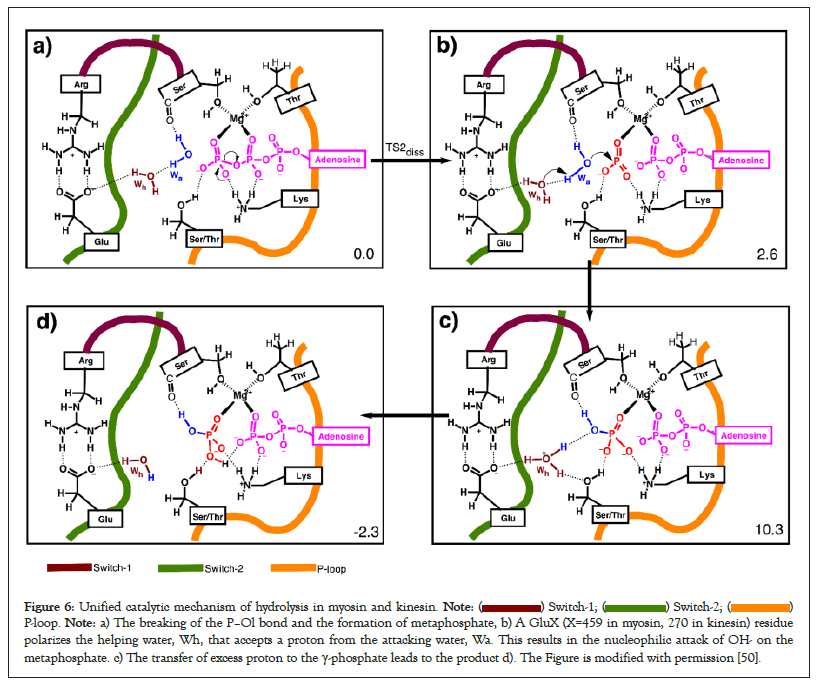

Strategies to facilitate P–O bond breaking: The phosphate- binding loop promotes P–Ol bond cleavage in ATPases Walker, et al. first pointed out in 1981 that the sequence of amino acids in the phosphate-binding loops (P–loop) of ATP hydrolyzing proteins (ATPases) is conserved [73]. We recently mentioned that the NH groups of these P-loop amino acids in ATPases form hydrogen bonds with the leaving α,β-diphosphate moiety of ATP (not displayed) to modify the nucleophile strength of the leaving nucleophile [50]. During hydrolysis, one negative charge has to shift from the terminal γ-phosphate to the leaving α,β-diphosphate group (Figure 4A). The direct hydrogen bond interaction of the NH groups of the P-loop with the leaving α,β-diphosphate attracts electron density away from the scissile P–Ol bond towards the leaving α,β-diphosphate group [50, 74-76]. Consequently, the departure of leaving α,β-diphosphate group and the shift of negative charge from γ-phosphate to ADP is made facile. This produces a meta-phosphate hydrate as an intermediate during the hydrolysis reaction (see unified mechanism of ATP hydrolysis in kinesin and myosin in Figure 6). Our calculations show that each peptide group significantly contributes in stabilizing the formation of a metaphosphate in myosin [33]. In the enzymes that hydrolyze phosphate esters (e.g., CRISPR and EcoRV), the leaving group is poor (strong nucleophile) (Figure 4B). In such cases, protonation of a leaving group by an Mg2+-coordinated water to the bridging P–O–C oxygen has been suggested to break the P–O bond and facilitate the charge shift from the phosphate reaction center towards the leaving group [48]. In the case of Alkaline Phosphatase (AP), however, stabilization from active site residues and water molecules appears to be sufficient to make AP one of the most proficient enzymes [68] (Figure 4).

Figure 6: Unified catalytic mechanism of hydrolysis in myosin and kinesin.  P-loop. Note: a) The breaking of the P–Ol bond and the formation of metaphosphate, b) A GluX (X=459 in myosin, 270 in kinesin) residue

polarizes the helping water, Wh, that accepts a proton from the attacking water, Wa. This results in the nucleophilic attack of OH- on the

metaphosphate. c) The transfer of excess proton to the γ-phosphate leads to the product d). The Figure is modified with permission [50].

P-loop. Note: a) The breaking of the P–Ol bond and the formation of metaphosphate, b) A GluX (X=459 in myosin, 270 in kinesin) residue

polarizes the helping water, Wh, that accepts a proton from the attacking water, Wa. This results in the nucleophilic attack of OH- on the

metaphosphate. c) The transfer of excess proton to the γ-phosphate leads to the product d). The Figure is modified with permission [50].

Strategies to lower the energy barrier to the OH bond breaking: Proteins employ a catalytic base to avoid direct proton transfer from the attacking water to γ-phosphate: Direct proton transfer from the attacking water to the γ-phosphate results in an extra proton (positive charge) on terminal phosphate. This direct proton transfer attracts electron density away from the P–Ol bond in the direction opposite to direction of charge transfer (see the pulling effect of γ-protonation and the direction of the charge shift in Figure 6). This delays the breaking of P–Ol bond and leads to a sequential type Oa–H mechanism if the leaving nucleophile is also a strong nucleophile (Figure 2, top panel) or a concurrent mechanism if the leaving nucleophile is mild or weak (left panel in the second row of Figure 2). Many enzymes use a proton relay mode so that the phosphate reaction center indirectly accepts a proton later during the reaction after the breaking of the P–Ol bond (see base-assisted sequential type S mechanism in Figure 2). This results in the formation of a hydronium ion during the reaction. Existence of hydronium ions in proteins has also been confirmed experimentally [76].

Hydrolysis reaction of phosphate containing compounds is subject to extensive computational and experimental research. Based on the most recent computational studies by us and others, we present a unified theoretical model in which hydrolysis reactions are arranged on the basis of a) the sequence in which O-H and P-O bonds break b) the nucleophile strength of the leaving group and c) the modes of proton transfer from the attacking water molecule to the phosphate reaction center. The salient features of the presented scheme are as follows:

• Hydrolysis reaction of phosphate containing compounds requires the breaking of two bonds i.e. the O-H bond of the attacking water and the P-O bond of the phosphate containing species. Enzymes have specialized residues to catalyze both bond breaking events.

• There exist two mechanisms for proton transfer from the attacking water to the phosphate containing substrate during hydrolysis, i.e., a) direct proton transfer from the attacking water to the phosphate reaction center, and b) indirect proton transfer from the attacking water to the phosphate reaction center via a mediating water molecule or a protein residue.

• For the direct proton transfer, hydrolysis reaction of phosphate containing compounds can be classified based on the sequence in which O–H bond of the attacking water molecule and the P–O bond of the substrate break.

• The resulting mechanisms of hydrolysis can be arranged based on the strength of the leaving nucleophile.

• Enzymes avoid direct proton transfer mode from the attacking water to the phosphate containing compounds. They rather use indirect proton transfer mode by placing a suitable base in the vicinity of the attacking water that accepts proton from the lytic water to facilitate the Oa–H bond breaking and later transfers it to the phosphate reaction center. In the indirect mode, the proton transfer from the attacking water proton to the phosphate containing compound is delayed. This further facilitates the departure of the leaving nucleophile.

• Enzyme catalytic strategies are further fine-tuned to the substrate being hydrolyzed. For instance, ATPases place suitably oriented P-loop NH groups to directly polarize the leaving α,β-diphosphate moiety and decrease its nucleophile strength and facilitates P–Ol bond breaking.

These insights into the mechanism of hydrolysis have been made possible due to the fact that larger quantum mechanical regions containing catalytically critical protein residues or larger explicit solvation shell can now be included in the QM or QM/ MM setups. Increased computational power also means that calculations with computationally expensive methods such as the refinement of whole minimum energy paths can also be carried out.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref ] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar].

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar].

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar].

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref ] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Hassan HA, Rani S, Kiani FA, Fischer S, Aslam S, Sikandar A (2023) A Comprehensive Theoretical Model for the Hydrolysis Reactions of Phosphate Containing Compounds. J Theor Comput Sci. 09:179.

Received: 21-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. JTCO-23-21871; Editor assigned: 24-Feb-2023, Pre QC No. JTCO-23-21871 (PQ); Reviewed: 10-Mar-2023, QC No. JTCO-23-21871; Revised: 17-Mar-2023, Manuscript No. JTCO-23-21871 (R); Published: 24-Mar-2023 , DOI: 10.35248/2376-130X.23.09.179

Copyright: © 2023 Hassan HA, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.