Journal of Oceanography and Marine Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2572-3103

ISSN: 2572-3103

Short Communication - (2019)Volume 7, Issue 1

Vanadium is – next to molybdenum – the second-to-most abundant transition metal in sea water. Oxygenated sea water commonly contains 24-45 μM of vanadate H2VO4ˉ (and is thus – next to molybdenum – the second-to-most abundant transition metal in sea water) with the levels mainly fluctuating with the season. Depletion by about 60% can occur as reduction to VIVO2+ takes place which forms a sparingly soluble hydroxide, VO(OH)2, that is readily absorbed by particulate organic matter [1]. Consequently, the factors influencing the occurrence of vanadium are redox conditions (such as dissolved O2 and Fe2+, the presence of NH3 and S2), and – of course – its uptake by marine organisms. Vanadate is mainly taken up by marine algae, the most prominent one being knotted wrack (also known as rockweed) Ascophyllum nodosum, (Figure 1), by ascidians and, to some extent, also by some Polychaeta fan worms [2]. The significance of vanadium as an essential element in these organisms will be addressed.

Figure 1. Examples for algae that produce hypohalous acids: Left Corallina officinalis, right Ascophyllum nodosum, the alga where the vanadatedependent haloperoxidase was originally characterized by Vilter in 1983.

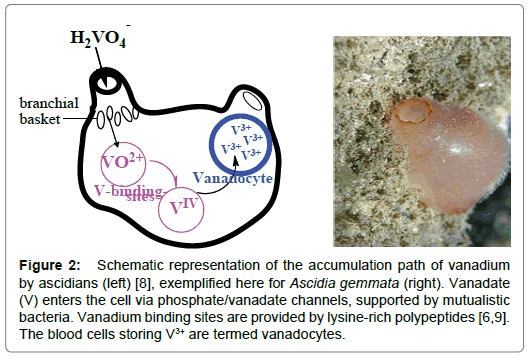

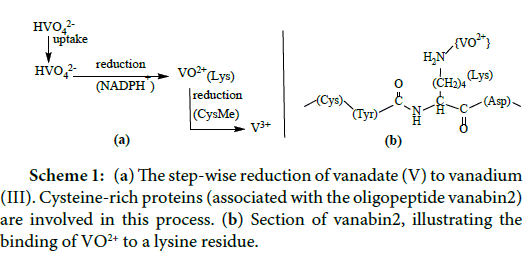

In 1911, Henze discovered vanadium in the blood cells (the coelemic cells; singlet ring cells and vacuolated amoebocytes) of the Mediterranean sea-squirt (ascidian) Phallusia mamillata [3]. The vanadium compound present in these cells actually is hydrated vanadium in the oxidation states of (predominantly) high-spin +III, such as V3+(H2O)x; the counter ion commonly is H2SO4ˉ. Vanadium is taken up by the ascidians (Figure 2) in the form of vanadate. After uptake, it migrates – via phosphate channels – into the cytoplasm of the organism in the form of H2VO4ˉ. Concomitant reduction takes place, which apparently occurs in two steps, i.e. (1) reduction of vanadate (V) H2VO4 - to oxidovanadium (IV) VO2+ by NADPH+ and (2) reduction of VO2+ to (hydrated) V3+ by cysteinylmethionine (CysMe) (Scheme 1) [4]. In addition, vanadium accumulating ascidians dispose of an enhanced capacity to metabolize glucose-6 phosphate (G6P); the activity of G6P-dehydogenase is markedly elevated when compared to ascidians with low accumulation rates [5]. The intermittently formed VO2+ binds to the lysine NH2 residues of the vanabins. Vanabins are lysinerich polypeptides of about 10 thousand kDa, attaining a bow-shaped conformation, with four α-helices connected by nine disulfide bonds [6-8].

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the accumulation path of vanadium by ascidians (left) [8], exemplified here for Ascidia gemmata (right). Vanadate (V) enters the cell via phosphate/vanadate channels, supported by mutualistic bacteria. Vanadium binding sites are provided by lysine-rich polypeptides [6,9]. The blood cells storing V3+ are termed vanadocytes.

Scheme 1: (a) The step-wise reduction of vanadate (V) to vanadium (III). Cysteine-rich proteins (associated with the oligopeptide vanabin2) are involved in this process. (b) Section of vanabin2, illustrating the binding of VO2+ to a lysine residue.

The amount of vanadium accumulated by ascidians strongly differs. An extraordinary degree of vanadium – up to 350 mM and hence the about 107 fold of vanadate in sea water (~35 nM) – can be absorbed. In the intestinal lumen, the concentration can reach 0.7 mM. This particularly effective accumulation of vanadium, occurring in the greater part of the ascidians, apparently is supported by bacterial genera such as Pseudomonas and Ralstoni (in the tissues of the branchial sacs of the ascidians), and Treponema and Borrelia (in the intestines) [9-12] – a fact which is in line with the general ability of certain strains of bacteria from deep-sea hydrothermal vents (such as Pseudomonas vanadiumreductans) that reduce vanadate to vanadium in the +IV (and +III) state, using lactate as electron donor [13].

Several species of macro-algae in the marine environment (Figure 2) are able to catalyze the oxidation of the halide Xˉ (Xˉ = Iˉ, Brˉ, Clˉ) to hypohalous acid [14-17], as exemplified for the bromide oxidation in eqn. (1). The oxidant employed by these algae is hydroperoxide (H2O2, HO2ˉ); the oxidation is supported by heme-type or by vanadatedependent enzymes, viz. haloperoxidases. Pseudohalides, such as cyanide and thiocyanate (eqn. (2)) can also be substrates. By producing hypohalous acid, the algae protect themselves against parasite infestation, in particular fungi. A few other groups of organisms also oxidize halides to hypohalite, among these marine Streptomyces [18], bacteria and cyanobacteria [19,20]. In the latter case, chlorinated compounds are formed that function as antibodies.

Brˉ + H2O2 → BrOˉ + H2O (1a)

Brˉ + H2O2 + H+ → HOBr + H2O (1b)

SCNˉ + H2O2 → OSCNˉ + H2O (2)

The production of volatile, highly oxidative hypohalous acids HOX by some macroalgae does also have implications for the climate, since – once released into the atmosphere – HOX is subjected to UV irradiation and forms radicals that contribute to the depletion of atmospheric ozone [21]; eqns. (3) and (4).

CH3Br + hν → Br + CH3• (3)

Br• + O3 → BrO +O2 (4)

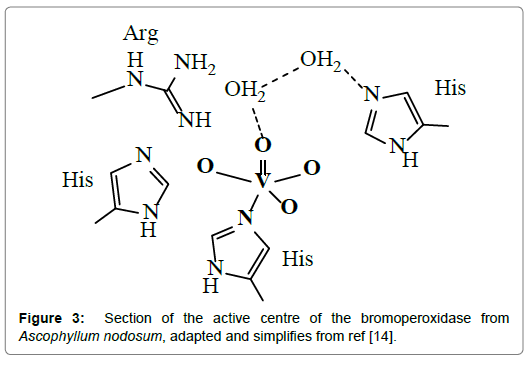

The active site (Figure 3) in all of these algae contains vanadium in an essentially trigonal-bipyramidal environment, in close hydrogen bonding interaction with surrounding water molecules and amino acid residues, cooperating with the active center via hydrogen bonds.

Figure 3. Section of the active centre of the bromoperoxidase from Ascophyllum nodosum, adapted and simplifies from ref [14].

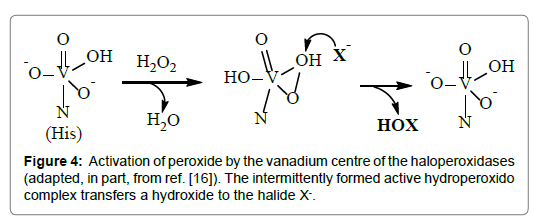

During turn-over, the VHPOs are self-supporting in the sense that they only marginally change their coordination environment. In the course of the reaction, a peroxido intermediate is formed, in which the trigonal-bipyramidal arrangement at the vanadium centre is essentially retained. H2O2 docks to the vanadium centre as hydroperoxide in a monodentate fashion, followed by the releases of one or two proton to form a η2-peroxido and/or -hydro-peroxido intermediate. This intermediate undergoes a nucleophilic attacked by the substrate, such as bromide, and finally releases hypobromous acid. The several steps of this sequence are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Activation of peroxide by the vanadium centre of the haloperoxidases (adapted, in part, from ref. [16]). The intermittently formed active hydroperoxido complex transfers a hydroxide to the halide X-.

Citation: Rehder D (2019) A Role for Vanadium in Ascidians and in Marine Algae. J Oceanogr Mar Res 7:190. doi: 10.35248/2572-3103.19.7.190

Received: 23-Feb-2019 Accepted: 13-Mar-2019 Published: 20-Mar-2019 , DOI: 10.35248/2572-3103.19.7.190

Copyright: © 2019 Rehder D. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.