Journal of Depression and Anxiety

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-1044

ISSN: 2167-1044

Review - (2019)Volume 8, Issue 4

Background: The delivery of interventions for traumatic stress disorders by paraprofessionals is of interest across mental health systems as decision-makers work to meet growing need for services and demand for evidence-based care. Given the need for any system change to reflect scientific evidence, our scoping review aimed to identify and summarize the research on paraprofessional-delivered trauma-focused psychological interventions for adults, with a particular focus on the role and training of paraprofessionals. Method: We searched seven databases for peerreviewed published studies that employed controlled trial designs to evaluate paraprofessional-led interventions for traumatic stress. Using Covidence software, we completed iterative eligibility screening and extracted study data. Descriptive statistics were used to identify trends and gaps in the literature and inform synthesis of findings.

Results: Fourteen studies met inclusion criteria. The majority of studies (71%; 10/14) evaluated interventions that were delivered face-to-face across a diverse patient populations and clinical contexts. Training of paraprofessionals ranged in length from two training sessions (approx. 16 hours) to a 6-week full day, in-person course. Ongoing supervision of paraprofessionals during the intervention was reported in 64% (9/14) of the studies, but few details of supervision processes were reported.

Conclusion: Paraprofessionals are taking on therapeutic roles in the delivery of trauma-focused psychological interventions but there are significant knowledge gaps around training and supervision they require. Lack of consensus on the defining characteristics of a “paraprofessional” makes synthesizing this literature particularly challenging.

Paraprofessional; Non-Specialist Health Worker; Post-traumatic Stress; Psychological Intervention; Health Service Planning; Review

AUDIT: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; ADHD-CSS: ADHD Current Symptoms Scale; BCQ: Brief Copes Questionnaire; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; Bespoke: Measures Without Validity Reported; CAPS: Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale; CBA: Controlled Before-After Trial; FACIT-Sp: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale; FFMQ: Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire; GHQ-12: General Health Questionnaire; HSCL-25: Hopkins Symptom Checklist 25; HTQ: Harvard Trauma Questionnaire; IES: Impact of Event Scale; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MOSSS=Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale; MPSS: The Modified PTSD Symptom Scale; NR: Not Reported; NRCT: Non-Randomized Controlled Trial; PC-PTSD: Primary Care-PTSD Screen; PCL-5: The PTSD Checklist for DSM-V-Civilian Version; PCL-M: PTSD Checklist-Military; PDS: The Post-traumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale; PSQ: Perceived Stigmatization Questionnaire; PSS: Post-Traumatic Stress Scale; PTSD: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder;

Prevalence, comorbidity, and burden

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a significant health problem that may develop following the experience of a traumatic event (e.g., combat, childhood abuse, sexual assault, accidents and natural disasters). Individuals with PTSD may not only experience aversive trauma-related symptoms (e.g., intrusive memories, distress when exposed to trauma reminders, negative changes in cognitions and arousal) but 62-92% also experience comorbid depression, anxiety, and substance abuse, which increase impairment, and distress [1,2]. Epidemiological research identified the lifetime prevalence of PTSD to be 6.8% among the general US population aged 15–54 years [3]. The effects of traumatic stress disorders extend far beyond the healthcare sector and affect quality of life and social and occupational functioning. Furthermore, the US Congressional Budget Office found that soldiers with (vs. without) PTSD incurred approximately four times more health care costs in the year post deployment. In a population study of Northern Ireland, the average cost of PTSD was $7118 CAD/year (productivity losses about two thirds of costs) [4,5]. The economic and social impact of PTSD is felt not only by those who experience the disorder, but also by families, co-workers, employers and the wider society [6].

Access to treatment

With current medications purported to have only a modest benefit [7], new psychiatric drugs still in early clinical trials, and some studies suggesting medication can do more harm than good [8], there are calls to revisit how we can better allocate existing human resources to meet the growing need for evidence-based psychotherapeutic interventions. Efficacious and cost-effective mental health treatments for PTSD have been well established [9,10], particularly the use of trauma-focused cognitive-behaviour therapy including exposure therapies. Despite the existence of evidence-based therapies, however, many people living with these disorders do not access these treatments. Barriers to accessing traditional psychological treatments include a lack of trained interventionists, limited insurance coverage and infrastructure, inequitable distribution of services, geographic isolation, lack of evidence-based protocols used by clinicians, social stigma associated with help-seeking, and lack of cultural appropriateness and acceptability of mental health care generally [11-15]. An epidemiological study in the US suggested that only 53% of individuals with a history of PTSD had received any type of treatment [16]. Low service utilization rates are also evident in lowand middle-income countries; a study in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa found that just under half of those who qualified for PTSD had accessed health care services [17].

Task-sharing models of mental health care and the increasing role of paraprofessionals and non-specialized health workers

Providing accessible, affordable, evidence-based psychotherapy for PTSD (and other mental health problems) is an ongoing public health challenge and one that has persisted for decades [18,19]. Fifty years ago policy advocates were making comments that eerily echo modern concerns:

"Professional manpower cannot meet the mental health needs of the population through present methods and there is no reasonable hope that such manpower can be sufficiently increased to do so in the future" [20].

“The resources available to tackle the huge burden of these disorders are insufficient, inequitably distributed and inefficiently used, which leads to a treatment gap of more than 75% in many countries” [21].

The enormous scarcity and inequality in the distribution of specialist mental health professionals [22,23] underscores the growing interest in new models for mental health services and addressing the system level issues that have resulted in these decades long issues.

A redistribution of mental health services, known as task-sharing/ task-shifting from specialist mental health professionals to nonspecialist health workers in community settings [24], is gaining momentum. Researchers and practitioners have proposed transforming the role of psychiatrists, psychologists, and psychiatric nurses from service-delivery to public mental health leadership to overcome this shortage of specialist care [25]. This role involves designing and managing mental health treatment programs, building clinical capacity in primary care settings, supervision and quality assurance of mental health services, and providing consultation and referral pathways that support self-management and skill building through stepped care [26]. To complement this change, licensed non-mental health specialist professionals (teachers, nurses) or unlicensed paraprofessionals would take on more aspects of direct mental health service delivery, a practice that is increasingly legitimized through expanded insurance coverage for peer and allied health professional programs [27,28].

The public are already access a variety of mental health services and supports from non-professionals (typically less than a master’s level degree) through peer support, coaching, advocacy, case management or outreach, crisis worker or assistive community treatment workers [29]. Paraprofessional-led interventions are increasingly more socially accepted in health fields, and have demonstrated no significant differences in service satisfaction when compared to professionally led interventions [30]. As these services become more mainstream increased attention has been put on credentialing, establishment of formal associations, and structured curriculum and training processes. For example, in the US the Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute and the Institute for Public Health Innovation both offer community-health worker and paraprofessional courses or certification.

To date, systematic reviews have examined the impact of paraprofessional-delivered interventions for other medical and wellness-focused domains including parenting programs [31], general mental health and illness [32,33], health and wellness coaching [34]. Across studies, equivalent, and at times superior, outcomes have been reported for paraprofessional-delivered interventions when compared to professionally led treatments [35- 38]. Despite these promising findings, given the variability in the characteristics and severity of illnesses investigated, it is important not to assume that paraprofessional-delivered interventions will be as promising when applied to PTSD populations. Given the potential severity of PTSD and its comorbidities, professionals may have concerns about paraprofessionals working with such complex problems. As such, a specific focus on the use of paraprofessionaldelivered interventions for PTSD is warranted.

Interventions for traumatic stress disorders using non-mental health specialists are growing across a diverse range of clinical contexts including for women who have experienced domestic violence [39], first responders [40], refugees [41], and survivors of natural disasters [42]. There have been a few reviews exploring the effectiveness of paraprofessionals in delivering mental-health care in low- and middle-income countries [43,44] but none involving the research in North America or European countries where many “coaching” and “wellness navigator” programs are being commercially offered. A 2013 Cochrane review summarizing this body of research for low to middle income countries indicated that task-sharing models may improve clinical outcomes for Post-traumatic stress disorder [45], and may be cost-effective [46]. As mental health funding becomes more contingent on evidence-based practices, paraprofessionaldelivered support programs for PTSD need to articulate standards and define the ways in which they create new operational processes and therapeutic roles as well as clarify the kinds of paraprofessional tasks and support that people find useful. Other health fields are quickly advancing consensus around core competencies and skills for paraprofessional coaches within their scope of work [47-49].

Given current problems with access to evidence-based PTSD interventions and the promising role of paraprofessionals in psychological intervention delivery, the present scoping review aimed to explore existing research on paraprofessional-led psychological interventions for PTSD specifically. We sought to expand previous reviews to consider studies from high income countries, include the most current research in the field, and include controlled but non-randomized study designs to capture a wider range of intervention research. In addition, as previous reviews have not given attention to the training and supervision protocols used with paraprofessionals within intervention studies, our review maps those gaps. Results will inform future work and have practical implications for communities, clinics, insurance providers, and healthcare systems interested in the implementation of paraprofessional-delivered interventions.

We conducted a scoping review following the framework of Arksey and O’Malley [50] comprising the five stages discussed below. Our approach adhered to recently updated reporting guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [51].

Stage 1: Review aims and research questions

This scoping review helps describe the evidence base for this service approach (i.e., paraprofessional-delivered psychological interventions for Post-traumatic stress among adults) and distill key professional contexts, activities, and training protocols in the research of paraprofessional-delivered interventions. The research question guiding the scoping review was: What are the characteristics of paraprofessional-delivered interventions for traumatic stress disorders? Secondary questions were:

(1) What are the demographic characteristics (clinical, socioeconomic etc.) of the populations in which the use of paraprofessionals to treat traumatic stress disorders has been studied?

(2) What specific therapeutic activities does the paraprofessional facilitate in these interventions for traumatic stress disorder?

(3) What adverse events do paraprofessionals encounter in the administration of traumatic stress interventions?

(4) What methods and approaches to training and supervision of paraprofessionals are used in traumatic stress interventions?

(5) What are the educational background and prior experience of paraprofessionals delivering traumatic stress interventions?

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

The search strategy for the present scoping review was developed in consultation with a trained librarian and evidence synthesis expert. The expert played a key role in determining and testing appropriate keywords, MESH terms, and filters to maximize sensitivity and specificity within the search. Publication titles from a preliminary search were reviewed to inform refinement of search terms in consultation with our team. The expert was instrumental in modifying and applying search terms to comply with the various bibliographic databases. We identified seven relevant databases: Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, CINAHL, Ovid PsycINFO, Ovid Cochrane CENTRAL, and Scopus. Search terms used included combinations of population (e.g., “traumatic stress”, “PTSD”); provider (e.g., “paraprofessional”, “community health worker”) and study design (e.g., “trial”, “controlled”) key words). Supplemental File 1 provides an example of a search strategy used for one of the included databases. The search was performed in May 2018. We included studies published since 1995. We reviewed the references of included studies to ensure that no additional studies should be included.

Step 3: Selecting the studies

We included only original/primary research articles published in English. Studies included in the present review could be randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized controlled trials (NRCTs), or controlled before-after trials (CBAs). Eligible studies evaluated interventions among a sample of adult participants (majority of participants over 18 years of age) with a primary diagnosis of a “secondary” (sub-clinical, mild-moderate) or “tertiary” (recovery or disability stage) stress-related disorder or other specified trauma and stressor-related disorders. We did not a priori define what constituted a traumatic disorder but consistent with scoping review methods reported how the study authors reported and measured traumatic stress. We included studies that investigated the efficacy of a psychosocial (i.e., non-medicationbased) intervention delivered by a non-licensed paraprofessional via individual, group, or web-based modalities at inpatient, outpatient, crisis, outreach telehealth, community-based, or wellness clinics/ centres. At least 50% of the intervention had to be delivered by a paraprofessional and the study had to report some form of outcome data (e.g., level of functioning, symptoms, diagnosis, quality of life, etc.).

We excluded commentaries, systematic reviews and study protocols. We excluded studies published in non-peer reviewed publications (including grey literature and government reports). We also excluded studies in which participants had an overarching organic disease (e.g., HIV, cancer, diabetes) which was identified by the authors as the primary health condition of the population under study. Studies were excluded if the intervention was

(1) Delivered by family members or professionals (i.e., psychologists, social workers, nurses, teachers, physicians, psychiatrists),

(2) Not self-contained (e.g., could not be isolated from other treatments or interventions), or

(3) Focused on primary prevention or reducing the risk of exposure to a risk factor.

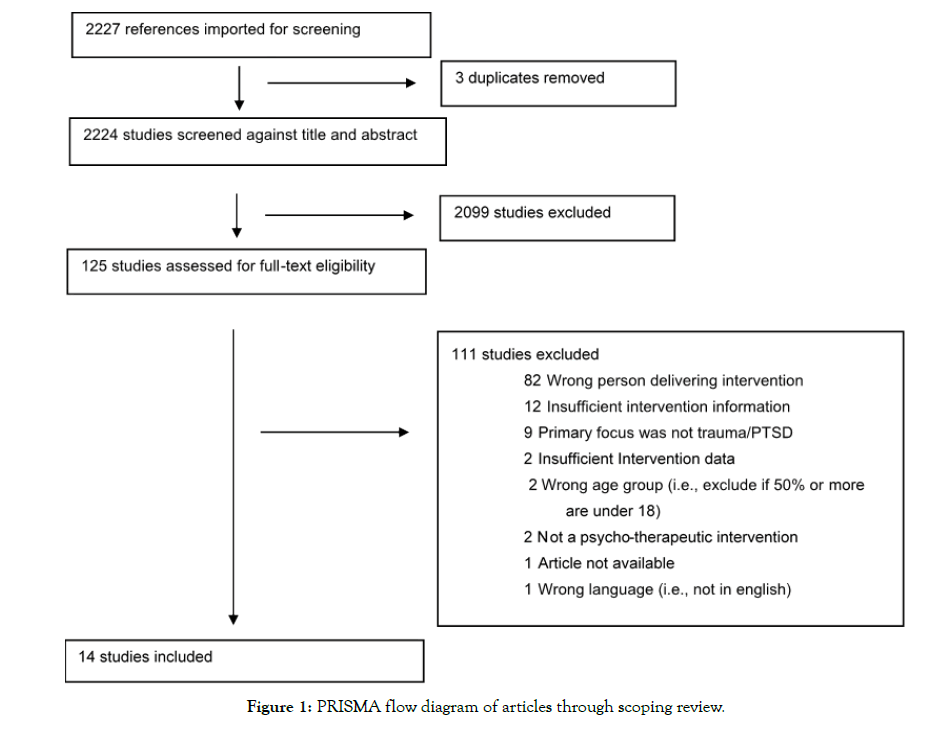

Selection of studies involved a two-phase screening process (Figure 1). After removing duplicates, we imported retained studies into Covidence software available through the Cochrane Collaboration (Covidence, Veritas Health Innovation). First, two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts based on inclusion criteria. Second, full text articles were reviewed and either accepted or rejected for data charting. Consistent with scoping review methods, inclusion and exclusion criteria were refined as familiarity with the literature increased [52]. Two reviewers independently screened 25 full-text articles to pilot-test our inclusion/exclusion criteria. Consensus and a third reviewer were applied to arbitrate disagreements and refine the parameters of studies to be included. After the initial 25 were reviewed, only one author screened the remaining full-texts. Any articles in which the reviewer was unsure were discussed with another team member.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of articles through scoping review.

Stages 4 and 5: Charting the data and reporting

We followed scoping review guidance [53] and extracted and reported on a comprehensive array of study variables that focus not only on outcomes but design characteristics, population characteristics, and other critical factors that inform interpretation. Relevant information was extracted into a data charting form (created in Microsoft Excel) to organize details useful for answering our research question. The full form, including a description of data categories, is available upon request.

All members of the team were involved in the development of the data extraction form. The form was piloted test independently by two researchers (TX, SR) for 7 articles. The form was then revised in consultation with an experienced reviewer (LW) to promote consistent and reliable extraction. Once the data extraction form was finalized, data extraction was performed independently by one researcher (TX) and reviewed by a senior researcher with extensive review experience (LW). Conflicts were discussed and where necessary a third author (PM) was consulted. The categories on the extraction form were based on the PICO mnemonic [54] (PICO: Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome).

Population characteristics: the country in which the study was conducted; disorder targeted; sample size; age, sex, and ethnicity/ race of participants; and methods used to identify psychiatric morbidity (e.g., diagnostic interview, self-report questionnaire).

Intervention and control characteristics: the person delivering the intervention; number of sessions prescribed; unit of intervention (minutes); number of sessions in total (actual); frequency of sessions (actual, in weeks); coaching/theoretical model(s) underpinning the intervention; delivery setting; peer involvement; types of activities involved (group session, homework, one-on-one counseling, physical activity); and paraprofessional qualifications, training, and supervision.

Comparator and study characteristics: lead author names; publication date; study aims; study design; data collection methods; follow-up assessments.

Outcome measures: severity and frequency of adverse events; specific measures used; and category of primary outcome measure (i.e., clinical, physical, cognitive, emotional, functional, work impact, relationships, relaxation skills, health system, acceptability of intervention, engagement with intervention)

A total of 14 studies met our inclusion criteria (Table 1). All studies were published after 2000 with 4 (29%) published in the last two years. The majority of studies (71%; 10/14) were RCTs with prepost data collection. Six of the studies (43%) conducted at least one follow-up at 6 months post-intervention or later. Most studies combined bespoke and validated measurement instruments with the two most common measures being the PTSD Checklist for DSM-V [55] and the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire [56]. The reviewed studies involved participants who had been exposed to both acute and complex repeated trauma. Paraprofessionals delivered interventions to war-and combat exposed refugees (5/14), survivors of natural disasters (3/14), survivors of gender or sexual violence (2/14), military veterans (2/14), care-providers (1/14), and pregnant women with postpartum PTSD (1/14).

| Authors | Country | Participants (N) | Study Design | Measures | Timing of Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuner et al. [57] | Uganda | Refugees with war-related PTSD (N=277) | RCT | PDS Bespoke: physical health checklist | Pre--test; post-test; 3-month f/u; 6-month f/u |

| Vijayakumar & Kumar [58] | India | Tsunami survivors (N=102) | Non-randomized control study | WHO-5; GHQ; BDI | Pre-test; Post-test |

| Becker et al. [59] | India | Women tsunami survivors (N=200) | Quasi-experimental design | IES Bespoke questionnaire | Pre-test; Post-test |

| Ertl et al. [60] | Uganda | Former child soldiers (N=85) | RCT | VWAES; CAPS; MINI; PSQ | Pre-test; 3-month f/u; 6-month f/u;12-month f/u |

| Connolly & Sakai [61] | Rwanda | Genocide survivors (N=171) | RCT | MPSS; TSI | Pre-test; Post-test; 2-year f/u |

| James & Noel [62] | Haiti | Earthquake survivors (N=60) | Non-randomized study (Pre--post) | HTQ | Pre-test; Post-test |

| Bass et al. [63] | Democratic Republic of Congo | Survivors of sexual violence (N=405) | RCT | HSCL-25; HTQ Bespoke: functional impairment assessment | Pre-test; Post-test; 6-month f/u |

| Church [64] | United States | Veterans (N=59) | RCT | PCL-M; SA-45; SUDs | Pre-test; interim; Post-test; 3-month f/u; 6-month f/u |

| Bolton et al. [65] | Thailand | Refugees (N=347) | RCT | HSCL-25 dePre-ssion subscale; HTQ; AUDIT Bespoke: sex-specific functional impairment scales; aggression questionnaire | Pre-test; Post-test |

| Dawson et al. [66] | Kenya | Women survivors of gender-based violence (N=91) | RCT | GHQ-12; WHO-DAS2.0; WHO-VAW; PCL-5 | Pre-test; Post-test |

| Bremner et al. [67] | United States | Individuals with combat-related PTSD (N=26) | RCT | CAPS; FFMQ; FACIT-Sp | Pre-test; Post-test; 6-month f/u |

| Jarero et al. [68] | Bolivia | Staff members who provide care for vulnerable people (N=37) | RCT | PCL-5 | Pre-test; Post-test; 90-day f/u |

| Weinreb, Wenz-Gross & Upshur [69] | United States | Pre-gnant women with postpartum PTSD (N=149) | RCT | PC-PTSD; SLESQ; BCQ; MOSSS; PSS Bespoke; overall health and substance use | Pre-test; Post-test |

| Rice et al. [70] | United States | Active military or veterans (N=133) | Pseudo-randomized control study | PCL-M; ADHD-CSS | Pre-test; Post-test |

Table 1: Characteristics of studies reporting on paraprofessional-led interventions for post-traumatic stress.

Most studies (71%; 10/14) evaluated interventions that were delivered face-to-face for at least 50% of the intervention duration. The remaining studies did not report on the method of intervention delivery with enough detail to make a determination (Table 2). Two interventions involved hybrid delivery. One studieds an intervention with face-to-face as well as phone-based support [57- 64] and another involved face-to-face and online support [65-70]. Five of the studies (36%) involved peers, not as the intervention deliverer but through some form of group-delivered activities. Interventions ranged considerably in intervention exposure (intensity and frequency of treatment) from brief (a single 40 min session) to intensive (36 two-hour sessions over several months). Among studies reporting sufficient detail on the level of exposure to the intervention, 82% (9/11) involved interventions with 5 sessions or more. A few interventions combined a typical weekly session with an intense full weekend or multi-day activity [67,70] (Table 2).

Descriptions of the specific therapeutic activities’ paraprofessionals facilitated were limited and heterogeneous. In one intervention, paraprofessionals were enlisted to provide befriending and “listening therapy” in which they did not provide advice but could explore pros/cons and possible courses of action with the participant and generally convey warmth and concern [58-60]. In another intervention, coaches delivered a fully structured manualized treatment program [60]. Interventions typically involved some form of counseling (64%; 9/14), group discussion (21%; 3/14), and/or written homework activities/manual (21%; 3/14). Two interventions incorporated physical movement (i.e., yoga) and one intervention incorporated artistic expression. None of the studies reported adverse events associated with the intervention. None of the studies reported on remuneration of paraprofessionals and only two studies explicitly described them as “volunteers”.

| Study | Duration of intervention | Single exposure duration | Freq. of exposure | Method of delivery | Format (ind. or group) | Peer support | Therapeutic activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuner et al. [57] | 6 sessions | 60-120 min | 2/week | NR | Individual | N | Counseling |

| Vijayakumar & Kumar [58] | NR | 60-90 min | 1/month | Face-to-face | Individual | N | Counseling |

| Becker et al. [59] | 36 sessions | 120 min | 3/week | Face-to-face | Both | N | Group discussion |

| Ertl et al. [60] | 8 sessions | 90-120 min | 3/week | Face-to-face | Individual | Y | Counseling |

| Connolly & Sakai [61] | 1 session | mean 40 min | NR | NR | Individual | Y | Demonstrations (e.g. role plays); counseling |

| James & Noel (2013) [62] | 12 sessions | 120 min | 3/week | Face-to-face | Group | N | Group discussion (seminars) |

| Bass et al. [63] | 12 sessions | 120 min | NR | Face-to-face | Both | N | Homework; counseling |

| Church [64] | 5 sessions | 90 min | NR | 52% face-to-face, 48% by telephone | NR | N | Counseling |

| Bolton et al. [65] | NR | 60 min | 1/week | Face-to-face | NR | Y | Counseling |

| Dawson et al. [66] | 5 sessions | 90 min | NR | Face-to-face | NR | Y | Counseling |

| Bremner et al. [67] | 9 sessions | 30 min and 360 min during week 6 | 1/week | NR | Both | N | Homework; self-help manual; media, physical movement (breathing and yoga exercise) |

| Jarero et al. [68] | 4 sessions | NR | NR | NR | Both | Y | Group discussion; art (draw pictures) |

| Weinreb, Wenz-Gross & Upshur [69] | 8 sessions | 30-40 min | NR | Face-to-face | Individual | N | Counseling |

| Rice et al. [70] | 8 sessions | In-person group: 120-150 min, 420 min between weeks 5-7; Online group: 90 min, 210 min between weeks 6-7 | 1/week | 49% in person, 44% online | Both | N | Homework; lecture; physical movement (yoga movement) |

Table 2: Overview of features and structure of paraprofessional-led interventions for posttraumatic stress disorders.

How the role of the paraprofessional was defined and described in the included studies was wide-ranging (Table 3). Almost every study defined the interventionist differently; the terms “lay workers,” “lay counselors,” “lay therapists,” “assistants,” “volunteers,” “advocates,” “mental health workers,” “community trainees,” and “instructors” were all used. Some of the studies (21%) did not report on the number or gender of the paraprofessionals delivering the intervention or whether the paraprofessional had prior experience in delivering that type of treatment. We were not able to determine typical caseload, the ratio of paraprofessional to intervention participant, or typical size of groups in group-delivered formats. Forty-three percent of the studies reported explicitly that the paraprofessionals had no prior experience in that role. All studies in our review reported that paraprofessionals “received training” but in 43% (6/14) of the studies no further detail on training was provided.

| Study | Intervention deliverer | Number and gender | Prior experience | Training | Training provider | Supervision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuner et al. [57] | lay counselors | 5 women, 4 men | No prior experience | 6-week course in general counseling skills and specific methods | 5 post-doctoral-and doctoral-level personnel | Case discussions in supervision meetings |

| Vijayakumar & Kumar [58] | volunteers | 4 women, 2 men | more than 4 years | 48 hours of training | NR | NR |

| Becker et al. [59] | community trainees | 10 | No prior experience | 3-day experimental train-the-trainee program | 3 psychiatric social workers; 1 psychiatrist | No supervision |

| Ertl et al. [60] | local lay therapists | 7 women, 7 men | NR | Received training | NR | Monitored by case discussions via video recordings |

| Connolly & Sakai [61] | paraprofessional therapists | 28 women, 1 man | NR | 2 day training | NR | Supervision conducted by the authors |

| James & Noel [62] | local earthquake survivors as mental health workers | 4 women, 4 men | No prior experience | Received training | Social workers, psychologists, and researchers | NR |

| Bass et al. [63] | psychosocial assistants | NR | 1-9 years of experience providing case management and individual supportive counseling | 2-weeks of in-person training. | NR | Employees of International Rescue Committee provided supervision through weekly telephone or in-person meetings |

| Church [64] | coaches | NR | NR | Received training | Licensed practitioners | NR |

| Bolton et al. [65] | lay workers | 11 women, 9 men | Two had prior general counseling experience | 10-day in-person training | Clinical team | NR |

| Dawson et al. [66] | lay health workers | 23 | No prior experience | 8-day training program and four weeks of practice cases under close supervision | Master trainer | Three Kenyan psychologists provide supervision for 1-2 hours a week |

| Bremner et al. [67] | instructors | NR | NR | Received training | A research psychologist with expertise in MBSR | The supervisor reviewed the recordings of sessions |

| Jarero et al. [68] | non-specialist mental health care providers | 12 | No prior experience | Received training | A certified therapist | Received supervision |

| Weinreb, Wenz-Gross & Upshur [69] | paraprofessional Pre-natal care advocates | 9 | NR | Received training | A certified seeking safety trainer | Two co-authors became certified seeking safety supervisors |

| Rice et al. [70] | experienced MBSR instructors | 2 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Table 3: Training and supervision characteristics of paraprofessional-led interventions for posttraumatic stress disorders.

Among those studies that did report more information on the type of training received by paraprofessionals, the smallest number of training sessions reported was two days [61] for an intervention with Rwandan Genocide survivors. The most extensive training provided was a 6-week in-person course [57] for paraprofessionals delivering an intervention to refugees with war-related PTSD.

Thirty-six percent (5/14) of the studies did not report who was responsible for the training of the paraprofessional(s). The remaining studies reported a variety of trainers including licensed professionals (psychologist, therapist, social worker) (6/14), a certified “seeking safety trainer” (1/14), or a “master trainer” (1/14). We found no information on the theoretical principles underlying training in any of the included studies.

Ongoing supervision of paraprofessionals during the intervention was reported in 64% (9/14) of the included studies. Very little information on the nature of the supervision was provided. Where some details of the supervision were reported, they included monitoring audio/video recordings of sessions (2/14) and individual case review with a psychologist or other allied healthcare worker (3/14). In at least two of the studies, the article author had acted as the supervisor.

Our scoping review sought to identify and summarize existing knowledge of the role of paraprofessionals in delivering psychological interventions for adults with traumatic stress disorders. The majority of studies included in our review were conducted in low to middle income countries, highlighting the paucity of knowledge about implementation within middle to high income countries where prevalence of traumatic stress remains high and access remains far below demand [71,72]. Within the public domain, even in middle to high income countries, there is a strong appeal for new ways of organizing trauma-focused mental health service delivery to increase access, reduce costs, relieve burden on overtaxed mental health care professionals, and connect clients with providers who are culturally competent and knowledgeable about the community. Yet, the systemization and integration of psychological interventions delivered by paraprofessionals have been slow within formal public health care systems.

Our review affirms that paraprofessionals are, in some instances, performing duties and processes related to treating traumatic disorders that were once considered solely the domain of the professional. Paraprofessionals in the included studies in our review completed such tasks as conducting in-depth one-onone counseling over multiple sessions, administering clinical assessments, and leading group-delivered psychoeducation. Many were completing these tasks without prior experience and only limited preparatory training.

While the studies included in our scoping review highlight the upcoming and ongoing use of paraprofessionals in Post-traumatic stress interventions, our review also highlights how far we, as a field, are away from understanding how to effectively use paraprofessionals as interventionists. Perhaps the diversity in even the word used to describe the paraprofessional (e.g., lay counsellor, non-specialist health worker, psychosocial assistant) is a perfect illustration of the heterogeneity of this field. The diversity of precipitating traumatic events participants experienced is also significant. The largest number of interventions were those targeting combat exposure or natural disaster related traumas – those experienced at a broad community level. Future research could provide important insights into why paraprofessional-delivered interventions are studied more often for community experienced trauma (e.g., war, earthquake) than for individually experienced trauma (sexual assault, parental abandonment). How traumatic experiences are socially and culturally interpreted in different communities may moderate and amplify the perceived “necessity” of relying on paraprofessional services. Our results highlight the need to explore this heterogeneity to uncover implementation facilitators at the community level that have not been previously considered.

This review raises many questions in terms of the role of paraprofessionals in traumatic stress interventions including

a) Exactly what roles paraprofessionals are taking on, including what intervention techniques and strategies they are delivering,

b) What the necessary and ideal amount and nature of training is needed to best prepare paraprofessionals to deliver interventions,

c) What, if any, background experience is necessary for paraprofessionals to be effective,

d) How supervision of paraprofessionals should be executed to be effective, evidence-based, and ethical, and

e) How paraprofessional delivery can be integrated with peer and/or professional involvement in intervention delivery.

Importantly, none of the previous reviews and meta-analysis on paraprofessional treatment delivery have explored the impact of different training and supervision models on treatment fidelity or efficacy and these mechanisms of change are a widely understudied area of research.

Our limited ability to map roles, training infrastructure, supervision structures, and remuneration models for paraprofessional-led traumatic stress interventions points to several directions for future policy and research initiatives. It is unclear within the research literature who is making determinations about qualifications outside of individual study authors and investigators. Our results point to a need to describe the qualifications and competencies of paraprofessionals and identify who within the health system is responsible for “fit for purpose” decisions around their work. Other health domains have undertaken processes to map consensus and disconsensus on core competencies [73,74] and may offer a template for how the field of mental health might transparently and comprehensively debate these important issues. The World Health Organization has suggested that for paraprofessionals to fulfill their role successfully, they require ‘regular training and supervision’ [75] but in the decade since that was advocated there remains little guidance around what form that should take. The included studies similarly provide little further insight.

Our review highlights limited knowledge sharing about the resources invested in selecting, training, and equipping paraprofessionals before they start providing services and the long-term and supervisory models that maintain the interventions as stable over time. This lack of reporting makes it exceedingly challenging for decision and policy-makers to mobilize evidencebased programs in new communities safely and with fidelity to the therapeutic frameworks believed to produce improved outcomes. Concerted efforts are needed to clarify best practices for training and supervision in the treatment of traumatic disorders via paraprofessionals.

This gap in knowledge is particularly notable given concerns and cautions about professional credentials in delivering mental health services discussed in the popular press [76] and research commentaries [77]. Ethical issues, privacy and confidentiality, liability, risk/suicidality, and lack of psychotherapeutic knowledge are all pointed to as the critical pitfalls in having paraprofessionals deliver mental health services to adults with traumatic stress disorders. Yet, these issues are given cursory attention in the reporting of intervention studies. For example, no adverse events were reported in the included studies but without clear reporting guidelines it is conceivable that adverse events occurred but were not seen as a reporting priority. Given the diversity of paraprofessionaldelivered psychological interventions and the scarcity of resources for mental health research future clear reporting guidelines for paraprofessional intervention studies would be beneficial [78].

Another important question raised from our findings is what falls under the umbrella of “paraprofessional”. Many studies in our review were excluded at the point of full-text screening because graduate students in psychology or other non-mental health professionals or (e.g., teacher, nurse) were the intervention deliverers. If the goal of a complimentary, integrated paraprofessional workforce is to massively open access to traumatic stress treatments then almostprofessionals and pro bono work by other professional worker groups seem a precarious sustainability plan. Unclear systems for remunerating the work of paraprofessionals even though they are providing clinical care raises important questions of equity fairness. Authors of the Cochrane Collaboration review of mental health services delivered by non-specialist health workers in low-middle income countries recommended future work focus on identifying strategies to integrate effective services and improve uptake within the health system. The conceptual and measurement dimensions proposed by Proctor (e.g., acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, penetration, and sustainability) [79] could be one lens from which to design and evaluate paraprofessional-led interventions in future research. This implementation science approach has been recommended in other recent reviews as well and could have a major contribution to closing the research to practice gap for treatment of Post-traumatic stress [80,81].

Finally, the body of literature from which to identify paraprofessional-led interventions is highly fragmented in terminology around the labeling of the role (e.g., non-specialist health worker, coach, lay counselor). Recent work by Olaniran to systematically map definitions of “community health workers” is an encouraging new development that needs to be further distilled within mental health specifically [82]. Without models and frameworks for understanding the paraprofessional role within the larger system and in relation to other health professionals, researchers will continue to struggle in defining, isolating, and evaluating the primary treatment ingredients of paraprofessional programs. Without theoretical clarity about the construct of “paraprofessional” work, we cannot further illuminate the nature of the paraprofessional's therapeutic influence. With increasing demand for trauma-focused care around the world, there is an urgency to close these knowledge gaps.

This scoping review has a few important limitations, which may impact its validity. First, due to the resources available, a systematic search of the grey literature and non-English published studies was not conducted. Second, the lack of standardized language, key terms, and labels to describe paraprofessionals may have resulted in some relevant studies being erroneously omitted. Third, we excluded studies which did not employ traditional experimental or quasi-experimental designs. It is possible that including different research designs may have expanded the number of studies in the review but may have also provided lower quality evidence. Third, following recommendations of the PRISMA- ScR protocol we did not generate summary statistics derived from meta-analyses so we cannot speak to the efficacy of the interventions in the included studies overall or in relation to the paraprofessionals’ role or level of training. Given the methodological heterogeneity of studies identified, however, a meta-analysis at this stage likely would be premature. As more primary studies become available in this field, future research could explore their combined efficacy and investigate dose-response relationships. Despite these limitations, this scoping review demonstrates that some paraprofessional-led interventions are being delivered with a diverse range of Posttraumatic stress populations and in many cases are being evaluated in controlled research studies.

Paraprofessionals may play an important role in broadening access to appropriate, evidence-based care. These findings will inform better reporting guidelines, bring focus to the training, supervision, remuneration, and qualification details of paraprofessional-led interventions, and inform ways to better integrate paraprofessionalled interventions into existing health care systems.

Not applicable

Not applicable

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Dr. McGrath is the founder and volunteer Board Chair of the strongest Families Institute that extensively employs paraprofessionals in mental health services.

Ting Xiong was supported by a Mitacs Globalink Research Internship with Dr. McGrath.

TX – Methodology, formal analysis, data collection and curation, investigation, writing original draft

LW – Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing original draft, review and editing, supervision, project administration

JO – Conceptualization, methodology, writing- review and editing

SR – Data collection and curation, visualization, writing- review and editing

PJM – Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing review and editing

We would like to acknowledge the evidence synthesis support provided by Leah Boulos at the Maritime SPOR Support Unit.

Citation: Xiong T, Wozney L, Olthuis J, Swati Singh R, McGrath P (2019) A Scoping Review of The Role and Training of Paraprofessionals Delivering Psychological Interventions for Adults with Post-traumatic Stress. J Dep Anxiety 8:342. doi: 10.35248/2167-1044.19.8.342

Received: 23-Aug-2019 Accepted: 06-Sep-2019 Published: 13-Sep-2019 , DOI: 10.35248/2167-1044.19.8.342

Copyright: © 2019 Xiong T, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Sources of funding : Ting Xiong was supported by a Mitacs Globalink Research Internship with Dr. McGrath.