Journal of Perioperative & Critical Intensive Care Nursing

Open Access

ISSN: 2471-9870

ISSN: 2471-9870

Research Article - (2023)Volume 9, Issue 1

Background: In Japan, in 1999, there was a "patient mix-up" in which two patients undergoing surgery had their lung and heart operations mistaken for each other. This medical malpractice triggered a growing concern for patient safety and became a social issue as the cause of the accident and the fragility of the medical care delivery system were revealed. Subsequently, the sedatives that had been administered preoperatively were no longer used, and patients began to walk into the operating room. With these changes, circulating nurses are expected to do their best to identify patients and care for them so that they can safely, and faces their surgeries in peace of mind.

Objective: This study aims to describe how circulating nurses in the OR (Operating Room) determine patients’ needs and provide care from the time a patient enters the OR to when they undergo general anesthesia. Methods: Fourteen OR nurses were observed during interactions with their respective patient and were later interviewed after the surgery. Data were analysed using thematic analysis.

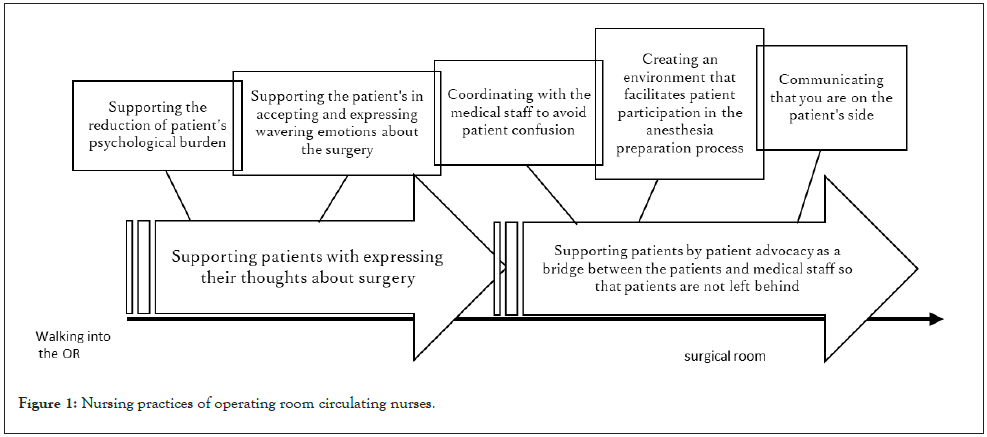

Results: The analysis revealed that the circulating nurses spent approximately 30 minutes with patients, doing their best to create an environment in which patients felt safe and peace of mind during the surgical procedure. Two major themes emerged in the analysis, including {Supporting patients with expressing their thoughts about surgery} until they entered the surgical room as well as when they were in the surgical room, and {Supporting patients by patient advocacy as a bridge between the patients and medical staff so that patients are not left behind}.

Conclusion: The OR (Operating Room) is an extraordinary place for patients that creates tension and anxiety, however for OR nurses it is an everyday space. Nurses need to be aware of this temperature difference in patient care. Nurses' interest in, and detailed observations of patients based on their professional knowledge and experience enable them to provide appropriate care, even within a limited period.

OR nursing; Circulating nurses; Nursing practice; Patient support; Patient-centered nursing; Thematic Analysis; Japan

In Japan, dedicated Operating Room (OR) nurses, who first emerged in practice in 1955, are placed into two categories: scrub and circulating nurses [1]. Scrub nurses assist the surgeon to ensure that the operation proceeds smoothly, while circulating nurses prepare for the induction of anaesthesia and provide physical and psychological support to ensure the patient's safety and peace of mind during the operation. In Japan, awareness regarding the importance of communication between patients and circulating nurses within the OR was initiated by a medical accident. In 1999, a "patient mix-up” occurred in which two patients undergoing surgery, one scheduled for a lung operation, the other for their heart, were mistaken for each other. Despite numerous opportunities, checks on the patient’s identities were not executed effectively [2]. Concern for patient safety heightened as the nature of this accident became public. It is now a common practice for patients to be carefully identified and verified. Pre-medications are no longer administered, and patients enter the OR on foot. Their identities are then confirmed by the OR nurses [3].

When surgery is performed under general and epidural anaesthesia, the duration from entering the OR to induction of general anaesthesia is generally 30 minutes. During this time, the circulating nurses meet the patient, perform an identity check, then guide the patient to the surgical room, and prepare them for the anaesthesia induction [4]. The reaction of OR nurses to patients entering the OR in a conscious state varies. Some nurses welcome the opportunity to communicate with patients and provide reassurance before surgery [5]. Conversely, reports suggest that "nurses do not have time to even keep patients safe because there is no time to spare,” and "nurses struggle to engage and pay attention to patients when they are so occupied with their safety [6,7].” Such differences in nurses' perceptions may reflect differences in priorities of care. What is the situation of experienced patients who undergo surgery? One study interviewed patients who had undergone surgery and reported that they described their experience upon entering the OR as becoming bewildered in the unfamiliar environment of the OR and they were unable to concentrate on anything other than the idea that they were about to have surgery since they were unable to hear anything else and further, they described their experience of undergoing surgery as "a realistic perception of the situation and a mixture of negative and positive emotions due to diverse factors, including the anticipation of the surgery [8].” In contrast, patients cared for by nurses who are trained in patient centered care, report that they feel reassured by the nurses’ knowledge, and that their dignity is protected by the nurses' willingness to be involved [9]. In consideration of the above, one might question the kind of support circulating nurses practice for patients who are about to undergo surgery in a state of anxiety and nervousness? The current study interviewed circulating nurses that reported: "they tried to predict the patient's condition upon entering the OR based on prior information about the patient and to provide reassurance by making eye contact and listening attentively [10,11].” In another study, it was reported that "they were striving to fulfill the security needs of their patients by providing a safe environment [12].” Despite such studies, no existing literature has reported a detailed description of how circulating nurses understand the situation, assess patients’ needs, and implement care through their interactions with patients.

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to specifically describe how circulating nurses in the OR (Operating Room) observe patients’ behaviour to determine their needs and respond appropriately from, when a patient enters the OR until the induction of general anaesthesia.

Design

This study is a qualitative study that utilizes thematic analysis.

Protection of Participants' Rights

This study was conducted with the approval of the Research Ethics Review Committee of the Graduate School of Health Management, Keio University (Approval No. 2018-11). To recruit participants, we first asked the OR head nurse of the three hospitals who cooperated in the study to introduce nurses with at least five years of OR experience who would fit the objectives of the study. Once identified and recruited, participants signed a consent form after receiving written and oral explanations regarding the purpose and procedures of the study, their voluntary participation, and withdrawal and confidentiality details. In addition, patients under the participants signed a consent form after receiving written and oral explanations of the purpose and procedures of the study and their voluntary participation.

Data collection

Data were collected from interviews with the study participants as well as from the interactions they had with their patients. Observational data were collected from the time the patient entered the OR (Operating Room), until the induction of general anesthesia. Interviews were conducted after the surgery, and the participants were asked to confirm their observations and intentional involvement as well as discussing their thoughts on nursing care as OR nurses. To begin the study, the researcher conducted preliminary training at the three cooperating hospitals to understand the OR environment, form relationships, and obtain recording consent from the medical staff associated with the study.

Data analysis

We performed a thematic analysis on the data [13]. First, we created a verbatim transcript from the data and examined it. Next, we extracted themes, focusing on the behaviors that were observed by the circulating nurses throughout their interactions with the patients to determine their needs and how they responded to them.

Rigor

This study used Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) guidelines and Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklists to ensure the quality of data analysis [14,15]. Data analysis and theme extraction were conducted by interviewing participants to confirm their perceptions of the observed situations, minimizing the researcher's subjective influence. In addition, data were analyzed by multiple qualitative researchers to collect and analyze data through triangulation.

In this study, 14 participants (all female) were observed during their involvement from patient entry into the OR (Operating Room) to the induction of general anesthesia at the three hospitals. Participants had 7-25 years of OR nursing experience (average: 14 years) and 7-27 years of nursing experience (average: 17 years). The 14 patients assigned to the study participants were 7 male and 7 female. Their ages ranged from 40-80 years, and their departments were respiratory surgery, gastroenterology, urology, gynecology, and orthopedics (Table 1).

| Nurse | ORN experience (Nurse experience) Year |

Patients | Age (male/ female) |

Clinical department |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kanazawa | 21 (24) | A | 74 (F) | Respiratory surgery |

| Yamaguchi | 14 (18) | B | 66 (F) | Gastroenterology |

| Matsue | 15 (15) | C | 68 (M) | Urology |

| Yokohama | 16 (16) | D | 77 (M) | Gastroenterology |

| Kamakura | 8 (25) | E | 56 (F) | Gynecology |

| Matsuyama | 17 (19) | F | 68 (M) | Gastroenterology |

| Kobe | 14 (14) | G | 44 (F) | Gynecology |

| Takamatsu | 9 (20) | H | 85 (M) | Orthopedics |

| Mito | 9 (9) | I | 69 (F) | Gastroenterology |

| Sendai | 7 (7) | J | 74 (F) | Gynecology |

| Maebashi | 11 (15) | K | 62 (F) | Gynecology |

| Utsunomiya | 8 (9) | L | 47 (M) | Gastroenterology |

| Osaka | 24 (25) | M | 80 (M) | Gastroenterology |

| Morioka | 25 (27) | N | 51 (M) | Respiratory surgery |

Table 1: Participants’ background information (n=14).

All study participants valued the first contact in establishing a trusting relationship with patients and anticipated the degree of tension and anxiety of patients based on prior information and experience. Accordingly, they devised approaches to alleviate patients' tension and anxiety, such as lowering the tone of voice and speaking gently, or using a cheerful and energetic voice, while carefully observing their reactions and considering the next steps in their involvement. In addition, when checking the patient's name band for identification, all participants were attentive to the patient, supporting the patient's arm gently from below.

Next, we describe the relationship between the circulating nurses and their patients. As a result of the analysis, two themes were extracted: {Supporting patients with expressing their thoughts about surgery} and {Supporting patients by patient advocacy as a bridge between the patients and medical staff so that patients are not left behind} (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Nursing practices of operating room circulating nurses.

{Supporting patients with expressing their thoughts about surgery}

The main part is nurses’ involvement with the patient from the time they enter the OR until they are moved to the recovery room. The purpose is to understand the patient's complex emotion in the OR, which is an unusual environment for the patient, and to support the patient in expressing their honest emotions about the surgery. This theme was generated from two sub-themes: [Supporting the reduction of the patient’s psychological burden] and [Supporting the patient's in accepting and expressing wavering emotions about the surgery.]

[Supporting the reduction of the patient’s psychological burden]: To support patients who have courageously verbalized requests that are difficult to express in a tense atmosphere, to understand the emotions of the patient, and to reduce the psychological burden so that they can remain calm.

Nurse Kanazawa's involvement with Ms. A after they entered the OR: Ms. A, aged 74, female, underwent thoracoscopic-assisted lobectomy. The anesthesiologist and resident physician quickly approached Ms. A as she entered the room and began to speak rapidly, while Ms. A, nodded to what the physician was saying with a nervous expression as if she was overwhelmed. After the anesthesiologist had finished speaking, Ns. Kanazawa quietly approached the nervous Ms. A. In a slow tone to ease her tension, she asked, "May I ask your name for confirmation?" she explained the purpose of the procedure and asked for her consent. Then, Ms. A's expression changed from a nervous one to a pleasant smile. Following this, and just before entering the surgical room, Ms. A stopped and asked with an awkward expression, in a low voice that only Ns. Kanazawa could hear, "Where is the restroom?" she asked.

Deciding on the need for support: Ns. Kanazawa decided that, regarding Ms. A's request to go to the restroom before entering the surgical room, there would be little impact on the overall surgery in terms of time. However, she surmised that it would have required a great deal of courage for Ms. A to request to go to the restroom at this time. Ns. Kanazawa considered that there was a risk that the elderly Ms. A would feel a psychological burden of shame by the medical staff, who were waiting for her, and decided on the necessary measures to deal with this situation.

Ns. Kanazawa's response and Ms. A's change: Ns. Kanazawa expressed her sympathy for Ms. A's need to go to the restroom as she walked quickly to the restroom, saying, "Its cold..." and "You're so nervous...”. Ms. A replied shyly, "I should have gone before I came,” Ns. Kanazawa waved her hand to the side to let her know that “It is okay,” and reiterated that she had plenty of time to go to the restroom, to which Ms. A responded with a "thank you,” clasping her hands in front of her face as if to express her gratitude. After several minutes, Ms. A came out of the restroom in a hurry, and Ns. Kanazawa extended the end of her sentence, "Please take your time..." in a slow tone of voice to convey that "there was no need to hurry.” Ns. Kanazawa saw Ms. A's awkward expression upon her return and intentionally mentioned the surgical site, and Ms. A stopped, smiled, and showed the markings of the surgical site, recovering her composure and walking at a slower pace.

[Supporting the patient's in accepting and expressing wavering emotions about the surgery]: To support the patient in expressing their feelings and emotions that are muddled by a mixture of anxiety and anticipation as the patient enters the OR, an unusual environment, and the reality of the surgery becomes more real.

Nurse Yamaguchi's involvement with Ms. B after they entered the OR: Ms. B, aged 66, female, underwent a pancreatoduodenectomy. Ms. B was initially feeling positive about the surgery; however, on the day she entered the OR with a stiff expression. Ns. Yamaguchi approached Ms. B with a cheerful voice and a smile to ease her nervousness, but Ms. B only nodded, her expression remaining stiff. As they began walking toward the surgical room, Ms. B looked at her feet as if to avert her gaze from the medical equipment in the hallway of the OR.

Deciding the need for support: Ns. Yamaguchi believed that Ms. B was becoming increasingly anxious owing to her few words and stiff facial expression, so she observed her carefully. Ms. B walked with a stiff expression, looking at her feet as she walked to the surgical room. Ns. Yamaguchi thought that Ms. B might be harboring shaky feelings about the surgery and looked for an opportunity for her to talk about these feelings before entering the surgical room.

Ns. Yamaguchi's response and Ms. B's change: Ns. Yamaguchi asked Ms. B "how were you last night?" while looking into her face as they walked. She replied, "I was able to sleep, but, well; I got nervous when I came here,” while her gaze remained downcast at her feet. Ns. Yamaguchi replied, "You got nervous..." Ns. Yamaguchi repeated just as Ms. B had said and slowed down her walking pace. Ms. B then looked at Ns. Yamaguchi and replied, "There are so many things in the hallway, and I am definitely nervous." Ns. Yamaguchi, perhaps thinking that Ms. B might speak her mind, stopped at the edge of the hallway, looked Ms. B in the eyes, and replied, "You get nervous when you see so many different things?" As if in response to these words from Ns. Yamaguchi, Ms. B began to talk about her expectations and anxieties about the surgery. Ns. Yamaguchi, based on her personal experience, thought it would be more effective to listen to Ms. B's nervousness while gently touching her, first rubbing her arm, and then putting her hand on her shoulder. That time was a minute or two, but when the talk was over, Ms. B looked refreshed and smiled at Ns. Yamaguchi, saying, "Mmm-hmm." Ns. Yamaguchi placed her hands on both of Ms. B's shoulders, looked her in the eye, and said, "I will explain every step in the surgical room as I go. Please ask me anytime if you need anything." Ms. B nodded twice happily, looked up, and began to walk slowly.

{Supporting patients by patient advocacy as a bridge between the patients and medical staff so that patients are not left behind}

This theme was generated from three subthemes [Coordinating with the medical staff to avoid patient confusion], [Creating an environment that facilitates patient participation in the anesthesia preparation process], and [Communicating that you are on the patient's side].

[Coordinating with the medical staff to avoid patient confusion]: Coordinating to avoid confusion in situations where a patient is forced to respond to requests from multiple medical staff at the same time.

Nurse Matsue's involvement with Mr. C after they entered the OR: Mr. C aged 68, male, underwent a laparoscopic nephrectomy. When he entered the OR, he was sitting with his legs together; hands on knees, back straight with a stiff expression, and his hands were sweaty when he touched them during the identification. In contrast, Mr. C sometimes joked with the resident and scrub nurse. Ns. Matsue, while understanding that Mr. C was highly nervous, was cheerful from the way he was joking and involved Mr. C and the other medical staff so that they could chat and laugh. Upon arriving at the surgical room, the novice nurse tried to start assisting Mr. C, who was sitting on the operating table and talking with the anesthesiologist, by guiding him to undress.

Deciding the need for support: In a surgical room, work sometimes proceeds at the pace of the medical staff. While Mr. C was talking with the anesthesiologist, the novice nurse instructed him to change his clothes and began assisting him. Ns. Matsue decided that it was necessary to accommodate Mr. C so that he would not become confused trying to meet the demands of two medical staff at the same time.

Ns. Matsue’s response and Mr. C's change: The novice nurse was attempting to encourage and assist Mr. C to undress, in spite of Mr. C being in the middle of a conversation with the anesthesiologist. Mr. C seemed to accept the assistance with a nervous expression. Ns. Matsue, who was a short distance away, saw this and immediately approached the novice nurse to quietly restrain him. She then made the environment conducive to Mr. C being able to concentrate on his conversation with the anesthesiologist. Later, when the anesthesiologist asked Mr. C a question, who was supine on the operating table, Mr. C's answer with gestures did not reach the anesthesiologist because the anesthesiologist's gaze was not directed toward him. Ns. Matsue noticed this and casually informed the anesthesiologist and Mr. C about his answer and that it would not affect the induction of anesthesia. Later, Mr. C gradually began to talk with the anesthesiologist while turning his attention to Ns. Matsue. When Ns. Matsue explained that "We are going to start preparing for anesthesia," Mr. C quickly held out his arm and cooperated with the blood pressure measurement, saying, "Thank you I’m counting on you.” Mr. C's expression was calm, a complete change from the stiff expression on his face when he entered the room.

[Creating an environment that facilitates patient participation in the anesthesia preparation process]: To help ensure that no patient is left behind by providing an environment that facilitates the patient's participation in the anesthesia preparation process, and by understanding the overall situation in the surgical room.

Nurse Yokohama's involvement with Mr. D after they entered the OR: Mr. D aged 77, male, with mild hearing loss, underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ns. Yokohama bent down and approached Mr. D. When she told him that she was the nurse who had visited him before the surgery, his expression softened with an "aha" sound. During the transfer to the surgical room, Ns. Yokohama asked Mr. D, who was walking with a serious expression, "Did you have a good night's sleep last night?" Mr. D seemed surprised that Ns. Yokohama was talking to him about a topic not directly related to the surgery. Consequently, when Mr. D arrived at the surgical room after a series of daily life conversations with Ns. Yokohama, his expression had softened.

Deciding the need for support: Ns. Yokohama anticipated that although Mr. D's nervousness was reduced, it would take time for him to move around, given his old age, hearing loss, drains being inserted, and infusions also being given. Therefore, Ns. Yokohama considered it necessary to support Mr. D in easily participating in the anesthesia preparation process so that the medical staff could work at their own pace and not leave Mr. D behind, potentially harming his dignity.

Ns. Yokohama's response and Mr. D's change: Ns. Yokohama assisted Mr. D, who was sitting on the operating table to undress, saying clearly, "Shall I undress from the right side where there is no intravenous drip?" Mr. D said, "Right," and pulled out the sleeve of his right arm himself. Ns. Yokohama then explained in easy to understand language, including precautions before the action, "Well, let's lie down slowly," and "Please take your time since the bed is small unlike a hospital room," and waited for Mr. D to start moving and assisted him. Gradually, Mr. D looked at Ns. Yokohama and listened to her explanation before acting, moving at his own pace. In preparation of the epidural anesthesia, when Mr. D took a lateral position for the epidural anesthesia, the resident doctor was about to touch Mr. D to correct his position. Ns. Yokohama anticipated that Mr. D would be startled and confused if he was suddenly touched without explanation, so before the resident corrected his position, asked Mr. D "I'm going to step back a little bit." Mr. D listened to Ns. Yokohama's explanation and cooperated in correcting his position without any confusion.

[Communicating that you are on the patient's side]: The nurse should always take an interest in the patient and convey that the nurse is on the patient's side so that the patient does not have to be reserved and patient with the health care provider.

Nurse Kamakura's involvement with Ms. E after they entered the OR: Ms. E aged 56, female, patient with a shy personality, underwent an extended hysterectomy. She had pain associated with the left iliopsoas muscle metastasis and had been informed in advance that an epidural catheter might not be placed due to her obese body type (BMI of 37). When Ns. Kamakura saw Ms. E, enter the OR with a stiff expression on her face, she cheerfully greeted her in a bright voice to ease her nervousness, but there was no change in her expression. Therefore, first Ns. Kamakura asked Ms. E how she had been last night to create an atmosphere in which it was easy to talk. Ms. E stated that she had not been able to sleep and that she had taken painkillers this morning. When Ns. Kamakura told her that "I am glad that you are able to take the painkiller internally" and that she acknowledged Ms. E's concerns as if they were her own, saying, "Let me check the pain each time”. Ms. E smiled and nodded, and the tense atmosphere in the room eased.

Deciding the need for support: Ns. Kamakura anticipated the appearance of physical pain within Ms. E due to the procedures required for anesthesia and position holding. As Ms. E's patient nature may have prevented the open expression of pain, she felt it necessary to check in as needed, letting her know that she was there.

Ns. Kamakura's response and Ms. E's change: Ms. E was in the left lateral position for epidural anesthesia. When Ns. Kamakura asked her about the pain, she said in a feeble voice, "A little (painful).” Ns. Kamakura immediately checked with Ms. E about the pain in her left lumbar region, adjusted her position with the anesthesiologist, and gently told Ms. E to not exert herself. Ns. Kamakura continued to monitor Ms. E’s pain by talking to her and making eye contact in between procedures. When the epidural anesthesia puncture began, Ns. Kamakura noticed that Ms. E's hand was straining. Given that speaking to her during the puncture might cause her to move, she chose instead to gently hold her hand. Ms. E squeezed Ms. Kamakura's hand, so Ns. Kamakura responded in kind.

This study showed that circulating nurses in the OR (Operating Room) spent approximately 30 minutes in proximity to patients, doing their best to create an environment in which the patients felt safe and had peace of mind during surgery. Specifically, they practiced {Supporting patients with expressing their thoughts about surgery} both before and within the surgical room, and {Supporting patients by patient advocacy as a bridge between the patients and medical staff so that patients are not left behind}. This section discusses the characteristics of such nursing practices.

Supporting patients with expressing their thoughts about surgery

Preoperative anxiety has been shown to affect intraoperative and postoperative outcomes, highlighting the importance of care within a circulating nurse's role [16]. However, the degree of anxiety and its expressions may or may not vary among individuals. Furthermore, it is not uncommon for OR nurses to either meet patients in the OR for the first time, or shortly before the induction of anesthesia, leading to a difficulty in determining the appropriate help toward reducing anxiety while building a trusting relationship.

The OR (Operating Room) can be an unusual environment for patients that is not easy to adapt to. When patients enter the OR, they are introduced by the nurse in charge; however, they do not know what the nurse will do for them nor what their level of involvement will be. Some patients believe they should not talk to medical staff in the OR about anything other than the surgery, particularly if the nurse in charge looks busy or in a bad mood [8]. In addition, some circulating nurses do not have time to focus on the patients as they are busy performing their routine tasks. However, the nurses in this study exhibited a deep interest in the patient, devising ways to approach the patient at first contact based on preoperative information, assessing the degree of their tension and anxiety, and utilizing touch and communication skills at the right time.

In this study, when Ms. A, an elderly woman, expressed her desire to go to the restroom before entering the surgical room, the nurses made sure that she did not act hastily because she felt ashamed for making the medical staff wait for her. The nurse, in an empathetic manner, told her “There was no need to rush,” enabling Ms. A to regain her composure.

In addition, the nurse, who carefully observed the change in Ms. B's walking posture, line of sight, and walking speed, found an opportunity for conversation on a casual topic, stopped at the edge of the hallway while demonstrating active listening, and matched her steps in an empathetic manner. This gradually led to Ms. B opening up and expressing her thoughts and feelings.

The commonality within these practices was the nurses’ ability to find clues to support the patients. Through closely observing patients’ reactions via casual conversation, and by responding promptly, the nurses created an environment in which the patients "could talk to each other.” Nurses who are interested in, and willing to, care for their patient can be expected to transform the patient-nurse relationship into a person-to-person relationship. Such involvement led to the patient's feeling cared for as a person, and in the surgical room, nurses were perceived as a dependable presence due to the trust that had been established.

Supporting patients by patient advocacy as a bridge between the patients and medical staff so that patients are not left behind

When the patient arrives in the surgical room, preparations for anesthesia begin, and the process tends to proceed at the pace of the anesthesiologist and other medical staff. However, often at this stage, the patient is not sure what to do, and their nervousness is high. According to previous research, patients can be so nervous that they are unable to understand anything other than what they are instructed to do [8]. It is easy to infer the patient's emotional state in this way. It was also reported "even though nurses are aware that they are practicing patient-centered care, in reality, they are mainly engaged in routine tasks and patients are not able to participate, and the reason for this is lack of communication with other medical staff and time constraints [17].” While a relationship is not formed with the patient, "even if you tell patients to ‘ask anything’, it is difficult for them to say anything, and they are likely to feel lonely and alienated as if they are being left behind.” To avoid putting patients in difficult situation, nurses should assume the role of a bridge between patients and medical staff.

For example, when the nurse saw Ms. C was being assisted by a novice nurse to undress during a conversation with the anesthesiologist, she quietly restrained her by hand rather than her words. Thereafter, by acting casually, such as connecting the conversation between the anesthesiologist and the patient at the perfect moment, the environment was adjusted so that the work was not delayed, and the atmosphere was not disrupted.

In addition, when Mr. D was positioning himself to receive anesthesia, the nurses attempted to have him move on his own without assistance. Mr. D was able to participate proactively in the process of listening to the nurse's explanations and then performing the procedure. He said the following regarding his relationship with the OR nurses, "It was very important to me to feel that I had my own personal nurse in charge [9].” We consider that Mr. D recognized the nurse as a person who understood him and developed trust in her. In addition, when Ms. E was in pain during the epidural anesthesia position, the nurse in charge consistently checked on her pain from the time she entered the room, and the nurse gently touched Ms. E’s hand, which was strained during the anesthesia, and Ms. E held the nurse’s hand back. Gently touching the hand is an act of caring for the person, and when Ms. E shook her hand back, the nurse said, “I could feel her unspoken feelings, and I strongly felt that I wanted to take care of her as much as possible.” They had an experience of sharing their pain through their hands. Ms. Kawashima continues to appeal to the nurses to "describe the art of healing through the allowance and reevaluate the value of hands [18].”

The participants in this study had more than seven years of experience and were able to act autonomously in caring for their patients. They had a good understanding of the role of each medical professional engaged in the OR and the OR as a whole. They interacted and communicated with patients calmly and actively, consistently involved them to build a relationship, and assumed the role of a bridge between patients and medical staff.

In summary, we consider that the nurses' involvement with patients undergoing surgery described in this study was a practice made possible by their knowledge, experience, and strong will to care, even within a limited time frame.

The data for this study were collected from nurses working in large hospitals. In addition, the fact that the study participants were exclusively female may have influenced the results. Therefore, future studies should include nurses from hospitals with varying OR (Operating Room) sizes and types of work, as well as the inclusion of male nurses.

The OR (Operating Room) is an extraordinary place for patients that creates tension and anxiety, but for OR nurses, it is an everyday space. Nurses need to be fully aware of this temperature difference in patient care. The nurses who participated in this study did their best to encourage patients who felt overwhelmed by the OR atmosphere and found it difficult to express their feelings. They were also able to adjust the environment so that the patients did not feel left behind. In addition, the nurses in this study were found to be interested in their patients, meticulous in their observations based on their professional knowledge and experience and utilized effective communication techniques tailored to their patients to provide patient-centered care.

The novelty of this study is that, it specifically describes how circulating nurses observe the behavior of patients to determine their needs and respond appropriately during the time between the patient's entry into the OR and the induction of general anesthesia.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the ORs of the three hospitals that cooperated with our study. Among them, we thank Yumi Akiba, OR nurse, Asahi General Hospital; Satsuki Fukuyama, OR nurse, Yokohama Rosai Hospital; and Etsuko Horikoshi, certified nurse “perioperative nursing,” formerly of Nagaoka Red Cross Hospital, for their efforts in coordinating hospital management and OR staff. These three nurses have not disclosed any affiliation that would pose a potential conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

We would also like to thank Editage for English language editing.

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

This study was funded by the Japan Perioperative Nursing Academy.

Citation: Matsuzaki A, Miyawaki M (2023) A Study of Nursing Practices of Operating Room Circulating Nurses in Japan: A Focus on Patient Support. J Perioper Crit Intensive Care Nurs. 9:218

Received: 20-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. JPCIC-23-21482; Editor assigned: 23-Jan-2023, Pre QC No. JPCIC-23-21482 (PQ); Reviewed: 06-Feb-2023, QC No. JPCIC-23-21482; Revised: 14-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. JPCIC-23-21482 (R); Published: 22-Feb-2023 , DOI: 10.35248/2471-9870.23.9.218

Copyright: © 2023 Matsuzaki A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.