Rheumatology: Current Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2161-1149 (Printed)

ISSN: 2161-1149 (Printed)

Case Report - (2021)

Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis (AAV) is a systemic necrotizing inflammation of the small vessels that commonly involves kidney, lung, upper respiratory tract, skin, gastrointestinal and occasionally peripheral nervous system. Central Nervous System (CNS) is less commonly affected(less than 10% of patients) and is generally part of a multi-organ scenario. Angiography (CT angiography, MRA, or digital subtraction angiography) should be performed but can be normal in half of the patients given the involvement of small-sized vessels, which are beyond the detection capacity of the procedure. Biopsy is rarely performed in clinical practice but can help diagnosis. A complete workup including infective and autoimmune serologies as well as cerebrospinal fluid analysis is required, especially in patients with isolated or inaugural CNS manifestations. Finally, in absence of biopsy and/or demonstration of CNS vascular involvement, diagnosis is often probabilistic and relies on the systemic context and the ANCA positivity. Treatment of AAV-related CNS involvement requires combination of high-dose glucocorticoids and an immunosuppressant, mainly cyclophosphamide. Rituximab may be another option in patients with a contraindication for cyclophosphamide.

ANCA; Vasculitis; CNS; Immunosuppressant; Glucocorticoid; Cyclophosphamide

Central Nervous System (CNS) vasculitis, with its myriad and evolving presentations, always poses a great diagnostic challenge for neurologists. It occurs either as part of a systemic vasculitis, or a primary disorder restricted to the CNS [1]. Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis (AAV) is a collection of relatively rare autoimmune diseases of unknown cause, characterized by inflammatory cell infiltration causing necrosis of small vessels, with few or no immune deposits [2,3]. Serologically, it is associated with a specific ANCA for myeloperoxidase (MPO-ANCA/P-ANCA) or proteinase 3 (PR3- ANCA/C-ANCA). In the clinical practice, AAV mainly includes Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA), Microscopic Polyangiitis (MPA) and Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA) or renal limited vasculitis [1]. AAV is rare with incidence ranging from 15 to 25/1 million in the general population [4]. AAV have a peak incidence at 65-75 years old, but may occur at any age, with a slight male predominance. Approximately one fourth to one half of patients with AAV will experience a relapse within several years. Clinical presentation comprises a wide spectrum of manifestations from the common nephrological, respiratory, dermatological, gastrointestinal symptoms to infrequent neurological and cardiac complications. Neurologic involvement is not uncommon in AAV throughout the disease course. CNS is affected in <15% of patients with AAV 5 but accounts for much of the morbidity in those patients [5-7]. However, the heterogeneous CNS symptoms in AAV may hinder early diagnosis among neurologists, causing treatment delays and disease progression, leading to relapses, or even death. Clinical presentation may be characterized by headache, focal neurologic deficits, seizures, ischemic stroke or subarachnoid hemorrhage [8-12]. Diagnosis is usually based on clinical CNS manifestations and multiple ischemic (sometimes hemorrhagic) MR lesions mainly affecting the white matter.

A 42-years old, normotensive, non-asthmatic lady, known to have poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (on insulin) for 20 years presented to us with intermittent headache, vertigo, blurring of vision for 3 months and unsteadiness of gait for last 1 month.

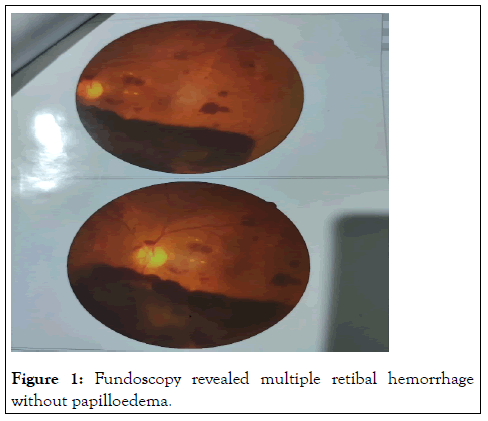

She denied any limb weakness, vomiting, altered sensorium, fever, seizure, speech swallowing or memory disturbances. She also reported short-term use of medications for suspected vascular headache with different NSAID’s, amitriptyline and propanolol but there was no history of taking any oral contraceptive of late. There was also no H/O cough, runny nose, nasal block, joint pain, skin rash, photosensitivity, oral or genital ulcer, hematuria, hemoptysis, epistaxis. She is a mother of two healthy children with no history of any abortion. Her family history was insignificant for any auto immune disease. On physical examination, she was hemodynamically stable with no skin rash or joint swelling. Neurological examination was suggestive of right sided cerebellar lesion as evidenced by presence of impaired finger nose test, heel shin test, and dysdiadochokinesis on right and horizontal nystagmus with fast phase towards the right. There was a bilateral retinal hemorrhage on fundoscopy without any papilloedema (Figure 1). Rest of the physical examination was normal.

Figure 1: Fundoscopy revealed multiple retibal hemorrhage without papilloedema.

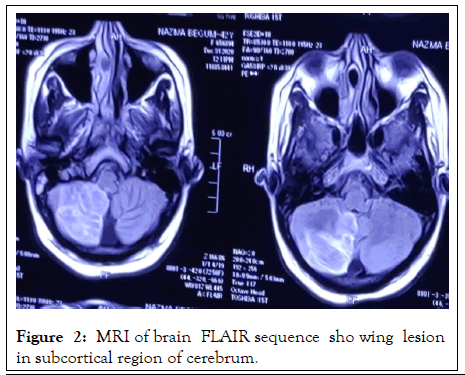

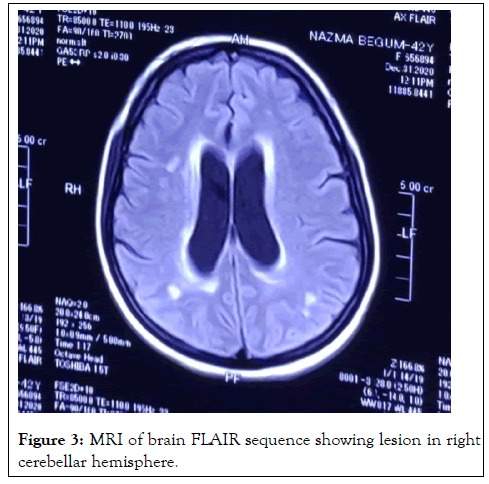

On investigation, complete blood count: mild normocytic normochromic anemia with Hb-10.93 gm% (MCV 83, MCH-27), ESR 60 mm in 1st hour, TC-10000/cmm (N-38%, L-54%), TPC-160000/cmm, CRP-58.5 mg/dl, PBF-normocytic normochromic anemia. Random blood sugar was high 21 mmol/L with HbA1c-11.8%. Urine R/E revealed; no proteinuria, RBC-2-3/HPF, but there were no granular, RBC or tubular cast. Serum ferritin was raised 535 ng/L. Serum albumin, SGPT, renal function tests (blood urea, serum creatinine, serum electrolyte), CPK, DCT, LDH, Blood C/S, Urine C/S all were noncontributory. CXR P/A, x-ray PNS, Echocardiography, X-ray of hands, USG of W/A revealed no abnormalities. Serological investigations for HBV and HCV were negative, VDRL non-reactive. On immunological test, ANA, Anti ds DNA, RA factor, Anti CCP, ENA profile, p- ANCA all came negative. Complement levels were normal. But c-ANCA came positive (10.5 U/ml, Normal <3 U/ml). MRI brain revealed white matter changes in subcortical region and over right cerebellar hemisphere (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: MRI of brain FLAIR sequence sho wing lesion in subcortical region of cerebrum.

Figure 3: MRI of brain FLAIR sequence showing lesion in right cerebellar hemisphere.

So final diagnosis of ANCA associated CNS vasculitis was made and she was started induction therapy with high dose oral corticosteroid (1 mg/kg/day) and oral Cyclophosphamide (CYC) (2 mg/kg/day). Blood sugar was appropriately controlled, bisphosphonates was also given. Argon laser therapy was performed to both eyes. On follow up after 4 weeks, her condition was improving. Tapering of steroid was initiated. There is a plan to continue induction therapy with tapering glucocorticoid and oral CYC for 3 months in total followed by maintenance therapy with azathioprine.

In general, extra-axial lesions involving the dura or pituitary gland are mainly attributed to granulomatous inflammation, while parenchyma pathologies are mediated by vasculitis and breakdown of blood brain barrier [13-18]. However, it remains unclear whether pathogenic ANCAs are produced intrathecally or from the systemic circulation and how the two ANCA serotypes contribute to different CNS manifestations.

Cranial nerves are rarely involved in MPA and EGPA (<5% of patients), however more frequently in GPA (up to 15% of patients) [15,18]. Optic and olfactory nerves are affected by spreading granulomas and peripheral cranial nerves (III-XII) can be involved because of pachymeningitis or other inflammatory process [19-23]. Clinical presentation involves visual impairment, olfactory impairment, facial nerve palsy, dysphagia and sensory disorders. Diagnosis is made upon neurological investigation and imaging studies (MRI).

This neutrophil-activation process is further augmented by the complement system, especially the alternative pathway, with C5a playing a key role in-between [24-30]. By contrast, the pathogenesis of extravascular granulomatosis is less wellunderstood. Current thinking holds that the chronic inflammation is initiated by the acute neutrophil-mediated necrosis [31]. Subsequently, defects in the cell death machinery and aberrant reaction of monocytes and macrophages contribute to the chronic inflammation and granulomatosis formation in AAV.

Neurological involvement is in majority of cases a part of generalized systemic disease, and as such should be treated. There is no specific treatment directed solely toward the neurological symptoms. The key issue is initiating AAV treatment as early in the disease course as it is possible [31-33]. Maintenance therapy is based on low-dose corticosteroids, Azathioprine (AZA) or Methotrexate (MTX) [34-36]. Recent studies proved efficacy of rituximab (RTX, monoclonal anti- CD20 antibody) in induction as well as maintenance therapy and according to the latest British AAV treatment guidelines it can be used interchangeably with CYC [37-39]. There are also encouraging reports about beneficial effects of intravenous immunoglobulins, especially for EGPA patients with residual neurological manifestations [40]. Therefore interdisciplinary approach is essential throughout whole patient care process and requires cooperation of the internists and neurologists. As there is no definite treatment for AAV, and the best thing we can achieve is remission, early treatment initiation or escalation in case of is lapse, can prevent from long-term, chronic organ damage, including neurological deficits. Although it is clear there are different phenotypes of the AAV, treatment regimens are now universal. Considering increasing research on systemic vasculitis, future will bring more therapeutic options for particular manifestations. Hopefully we will also be able to reduce complications of corticosteroids and highly potent immunosuppressant treatment.

AAV is a pauci-immune small-vessel vasculitis characterized by neutrophil-mediated vasculitis and granulomatosis. Hypertrophic pachymeningitis is the most frequent CNS presentation. Cerebrovascular events, hypophysitis, Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) or isolated mass lesions may occur as well. Spinal cord is rarely involved. Early recognition of AAV as the underlying cause for various CNS disorders is important for neurologists. Positive ANCA testing is highly suggestive of the diagnosis. Pathological evidence is the gold standard but not necessary. Once diagnosed, prompt initiation of induction therapy, including steroid and other immunosuppressants, can greatly mitigate the disease progression. Future studies are needed to better delineate the clinical spectrum of CNS involvement in AAV.

Conflict of interest

None declared

Citation: Gomes RR (2021) ANCA Associated Cerebral Vasculitis: A Rarest Presentation. Rheumatology (Sunnyvale). S18.004.

Received: 05-Oct-2021 Accepted: 19-Oct-2021 Published: 26-Oct-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2161-1149.21.s18.004

Copyright: © 2021 Gomes RR. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.