Anesthesia & Clinical Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-6148

ISSN: 2155-6148

Case Report - (2022)Volume 13, Issue 4

Lymphangiomas are congenital benign malformation of the lymphatic system, most commonly located in the head and neck region. The definitive treatment of lymphangiomas is surgery. Airway management in such patients is challenging in view of difficulty in visualizing the airway, difficult mask ventilation and intubation. The postoperative challenges include laryngospasm and airway obstruction due to airway edema caused by surgical manipulation. We report a case of massive lymphangioma of the neck in a 24-day old baby. Awareness of potential airway problems and possible complications is key to providing safe anesthesia to patients with lymphangioma.

Lymphangioma; Airway; Pediatric; Anesthesia

Lymphatic proliferation is a congenital defect that happens during early embryonic development when the lymphatic vessels are not formed properly [1]. The vessels may become blocked and enlarged as lymphatic fluid collects in the vessels. This forms as mass or cyst. There are two main types of lymphatic malformation: a) Lymphangioma, b) Cystic hygroma.

Airway management in these patients is always challenging especially in view of difficulty in visualizing the airway, distortion caused by extrinsic and intrinsic pressure on the airway, bleeding, enlarged upper airway structures and risk of sudden complete airway obstruction.

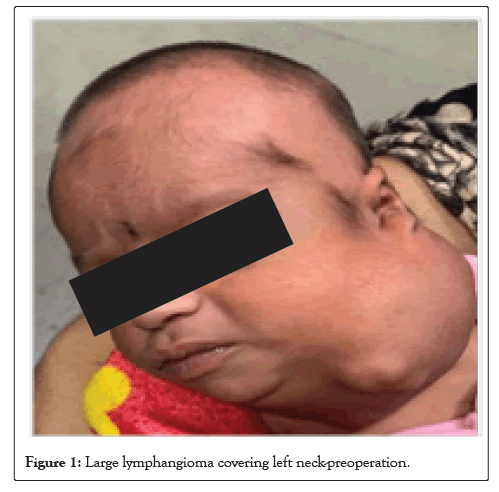

A 24-day old baby girl weighing 2.8 Kg presented with a huge swelling on the left side of the neck, sized approximately 15 × 13 cm, it was a full term normal vaginal delivery. Prenatal diagnosis was not done. On Clinical examination a large, smooth nontender mass covering the entire left neck up to infra auricular region (Figure 1). The skin looked normal with no signs of inflammation. Thorough preop evolution was done. Baby was warm, pink, and afebrile. Vitals were noted, heart rate 142/min and respiratory rate 42/min. No murmurs were present, and lung was clear. Abdomen was soft. Evaluation for concurrent anomalies like down syndrome or congenital heart defects was done.

Figure 1: Large lymphangioma covering left neck-preoperation.

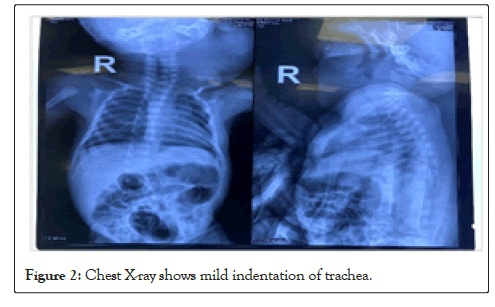

Chest X-ray was advised to assess the size and extent of neck mass to detect any potential for airway compromise thus avoiding soft tissue trauma during intubation (Figure 2) [2].

Figure 2: Chest X-ray shows mild indentation of trachea.

Cent neck

Evidence of a large well defined lobulated complex lesion in the left neck, involving the left parotid, sub mandibular, carotid, and parapharyngeal spaces, extending superiorly from infra auricular region to thoracic inlet inferiorly. It was seen to cause indentation and mild displacement of oropharynx, hypopharynx, and trachea. Lesion was predominately cystic, however, shows few hypodense areas, and calcific foci.

Investigation revealed a HB level of 18.4 g/dl and TLC count of 9800/mm3. Urine albumin and sugar was absent.

Her parents were counselled concerning the surgical procedure and fasting status. High risk consent was taken in view of possible difficult airway.

On arrival in operating room, routine monitoring (ECG, pulse oximeter, neonatal NIBP) were attached. Difficult airway cart and pediatric bronchoscope were kept ready to encounter any difficulty during intubation. A rescue tracheostomy by the ENT surgeon was available as a standby during induction [3].

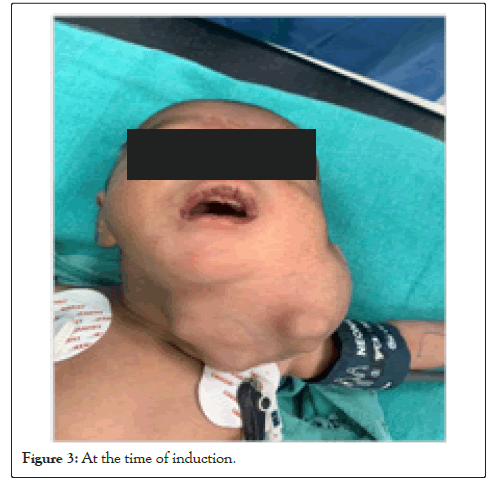

After securing intravenous access premedication was given with IV glycopyrrolate and fentanyl 3 mcg. Preoxygenation was done for 5 minutes. After ensuring adequate mask ventilation, inhalational of anesthesia was done with sevoflurane in titrated concentration (Figure 3).

Figure 3: At the time of induction.

When the patient was anesthetized, a gentle check laryngoscopy was done to visualize the glottis, but vocal cord was not seen and only the epiglottis could be visualized. The child was ventilated with mask and a second attempt of laryngoscopy was made with one assistant pushing the soft tissues towards left side. The glottis was visible, and trachea was successfully intubated with uncuffed ETT size 3.5 mm. It was confirmed with capnography and five- point auscultation.

Anesthesia was maintained with oxygen, nitrous oxide (66%) and sevoflurane. Injection fentanyl (2 mcg) and injection atracurium (1.5 mg) were administered and supplemental doses of atracurium (0.1 mg/kg) were used when necessary.

Blood loss was approximately 100 ml and was replaced. The duration of surgery was 2 hours. At the end of the surgery, neuromuscular blockade was reversed with injection neostigmine (0.05 mg/kg) and glycopyrrolate (0.01 mg/kg) and patient was extubated. Patient was shifted to post-operative care unit for observation and nursed in lateral position (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Post induction.

The incidence of lymphangioma has been reported to be 1.4 – 2.8 per thousand newborns [4]. Lymphangioma has a predilection for head and neck region, which accounts for about 75% of all cases. About 50% of all these lesions are noted at birth and around 90% develop by 2 years of age [5]. Airway obstruction occurs more frequently in newborns and young infants, although this tendency has not been statistically demonstrated [6]. Congenital lymphangioma may occur in association with Down syndrome, Turner’s syndrome, Noonan’s syndrome, and fetal hydrops [7].

The airway management in such type of cases always poses challenges for anesthesiologists. The major anesthetic concerns in our patient were regarding bag and mask ventilation, securing the airway by tracheal intubation, prevention of post-op respiratory difficulty and history of chest infection. Options for securing airway were awake intubation with intact reflex, inhalational induction with spontaneous breathing and invasive technique like tracheostomy. Since we could do proper bag and mask ventilation, we ruled out the possibility of an awake technique. We performed a check laryngoscopy to look if the visualization of the glottis was possible. Initially glottis was not seen but with adequate external manipulation it was visualized.

As in all potentially difficult airway cases, a thorough airway examination should be done. A complete history of recent upper recent respiratory infections is also necessary, as respiratory infections may exacerbate the lymphangioma by causing edema enlargement [8,9].

Frequent infection in the airway can lead to scarring and fibrosis, which can further block lymphatic drainage. The difficult airway cart needs to be well equipped before surgery. We should ensure the availability of face mask, nasal, and oral airway bougie, stylet, supraglottic airway device when anesthetizing such patients. There was an alternate plan for fiberoptic intubation in the event, that bag and mask ventilation was not feasible. Muscle relaxant should be used only after the airway has been secured due to possibility of complete airway obstruction. Extubating should be planned only in the fully awake active infants and without suspected airway edema. The patient should be shifted to NICU after observation as there is high risk of reintubation.

Anesthetic management of neonate with lymphangioma requires meticulous planning, preparation, and vigilance. It requires through knowledge of the disease and expertise in pediatric airway management. The definitive treatment of lymphangiomas is surgery. Airway management in such patients is challenging in view of difficulty in visualizing the airway, difficult mask ventilation and intubation. An effective communication and coordination between anesthesiologist and surgical team is the key to managing such difficult cases.

[Google Scholar][ Pubmed].

[Cross ref][Google Scholar][ Pubmed].

[Google Scholar][ Pubmed].

[Cross ref][Google Scholar][ Pubmed].

[Cross ref][Google Scholar][Pubmed].

[Google Scholar][Pubmed].

Citation: Kumar G, Sharma M, Kamal G (2022) Anesthetic Management of a Neonate with a Massive Lymphangioma. J Anesth Clin Res. 13:1056.

Received: 12-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. JACR-22-16740; Editor assigned: 14-Apr-2022, Pre QC No. JACR-22-16740 (PQ); Reviewed: 28-Apr-2022, QC No. JACR-22-16740; Revised: 03-May-2022, Manuscript No. JACR-22-16740 (R); Published: 16-May-2022 , DOI: 10.35248/2155-6148.22.13.1056

Copyright: © 2022 Kumar G, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.