Journal of Communication Disorders, Deaf Studies & Hearing Aids

Open Access

ISSN: 2375-4427

ISSN: 2375-4427

Research Article - (2020)Volume 8, Issue 2

This research started in Puerto Rico in December 2017, two months after Hurricane Maria in which art, like painting and drawing, was used as an expression strategy for Deaf students to share how they felt after this catastrophic event. Two years have passed since hurricane María, and still, there are Deaf students who demonstrate repressed feelings towards this event. It was necessary to continue exploring the drawing technique with Deaf students because this population did not receive assistance (emotional assistance) to express their feelings like hearing students received as part of the intervention protocols after disasters, such as hurricane María. Agencies and organizations like Red Cross, and the American Child and Adolescents Psychiatric Association identified the emotional needs of children and adolescents in the Island and provided psychological support to handle the emotional challenges faced. However, none of the interventions were geared to support the Deaf community. This lack of support motivated me to continue the investigation with Deaf students to aid in their need to express their fears and insecurities resulting from a catastrophic event to develop an appropriated intervention suitable to their communication style.

Deaf education; Catastrophic events; Art for comunication

On September 20, 2017 Puerto Rico was stroke with a category 4 hurricane, (María). Due to the severe damages to structures and services, many activities were put on hold for more than four months. Schools, for example, resumed classes in January 2018. Many people, including students, needed to receive emotional support to handle the fear and anxiety resulted from this catastrophic event. Local and Federal assistance took a long time to aid needy people, because streets and highways were blocked. However, for people with deafness those services were nonexistent because of the communication challenges that they have. The first interpreters used to provide access to information related to relief services, used American Sign Language, but many members of the Puerto Rican Deaf community, specially the older members, and did not understand the messages. The emotional aid was not available to the Deaf. Their communication needs were not met because professionals like psychologists do not know the manual communication used by the majority of Deaf people in Puerto Rico.

Information shared by agencies and organizations like Red Cross and [1]reported the identified emotional needs of children and adolescents in the Island and the psychological services provided to handle the emotional challenges faced. However, none of the interventions were geared to support the Deaf community. Thus, some Deaf students, after two years of hurricane María, still have repressed feelings about the event. This lack of support motivated me to continue exploring how the use of art could aid Deaf students to express their fears and insecurities resulting from a catastrophic event. As a teacher it was evident the need to develop an appropriated educational intervention suitable to their communication style. Specifically, this action research explored how art serves as a means of communication for Deaf students. Art was used as scaffold to assist Deaf students to create artistic expression of their feelings.

The problem addressed in this study is that Deaf students lack the communication skills to express their feelings, especially after a natural disaster or catastrophe, like a hurricane. Many of the students with deafness uses sign language as their prefer mode of communication. [2] states that sign language in Puerto Rico are the first language of the Deaf and not Spanish. Yet, most of the hearing population is unaware of this visual gesture language that Deaf people use as their first language. Moreover, their sign language is not known by the professionals that provide emotional aid, which in turn limits their access to such kind of services.[3]Found that the Deaf students in Puerto Rico face great challenges in their reading development, which is shown through inferior levels of reading comprehension compared to their hearing peers. On the other hand, [4] found that “deaf students [in Puerto Rico] have differences in their reading development”. [4,5]confirmed that the Deaf have a lag in their reading development. In a study done with Deaf pre-school children in Puerto Rico, [6]found that the lag in the language development shows that the deaf reach the school age without language skills, therefore they arrive in schools without the linguistics skills to develop reading and writing skills. These studies stress the difficulties encountered by the Deaf population in their reading development, which must be dealt with, in order to guaranty that they learn how to read and write.

Several investigations highlight that people with deafness present difficulties in language acquisition, not only in their oral form, but also in their written form [7,8]Mentions that this population presents serious challenges for language acquisition, not only in the oral form, but also in its written form.

In a world where most information is transmitted orally, for the deaf community, mainly the written word becomes one of the most valuable means to receive information, access knowledge and, as mentioned above, to be able to integrate to the society to which they belong. This is supported by [9], who say that "written language has the potential to provide the deaf child with an alternative mode of communication that allows him to access a lot of information ..." even so, being a very useful tool for this community, "... a large proportion of deaf subjects never reach competent reading levels." For the most part, deaf people graduate illiterate or with low performance from the written language, as well as from the pragmatics, syntax, and sociocultural elements of this oral language [10].

For this reason, diverse strategies must be used to achieve effective communication in and with this community, because communication is not an obligation, but a right. At present, in Puerto Rico, there is no strategy specially designed to facilitate the communication of feelings and emotions experienced by the Deaf population in catastrophic events. Worse, there are no strategies for this population to acquire reading skills that guarantee access to information, especially that related to catastrophic events. Art could be a scaffold for the Deaf people to communicate their feelings.

An additional aspect of the problem is the lack of professionals capable to meet communicative and emotional needs of Deaf people that emerge after traumatic events. Furthermore, the General Curriculum in Puerto Rico does not address the affective domain in any of the basic subjects (Spanish, Mathematics, Science, Social Studies/History and English), only the cognitive domain.

In 2017 I was studying a master’s degree in Differentiated and Special Education-Deaf Education at the University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras Campus. The first semester, which was supposed to startin August, started in December 2017, two months after Hurricane María. The course Education and Psychology of The Deaf (EDUC 6707) had the requirement to carry out a project where we must choose a problem faced by the Deaf community. The field experience was a real challenge because schools were not opened. My field experience was with two Deaf persons that I knew from the San Juan Metro area of the Deaf community. For me, the bigger problem was that the Deaf community was facing a lack of information related to Hurricane María, especially where to get the services that they needed.

During the hurricane, the Islands electric power collapsed, and there were no internet or cellular phone services. Given the fact that many Deaf people have a different language than the rest of the hearing community, access to information was, and still is the biggest challenge. Most of the communication was face to face, but many roads and high ways were blocked or destroyed by the hurricane. The social activities, as well as the social media that I used to socialize within the Deaf community with my Deaf friends, were also nonexistent for more than five months. Most of the hearing population in Puerto Rico was unaware that Deaf people in the Island were not receiving the information nor could get access to the services offered by the local and federal agencies to aid in the disaster. They were invisible to those in charge. After a month, I managed to meet in person with some of my Deaf friends and learned about their challenges and fears.

In order to help my friends and to meet my course requirements, I decided to use art to facilitate the expression of their feelings after the hurricane. I have a B.A in Special Education with a minor in Art education. I have used art in communication with my students in the mental health clinic that I worked as a teacher, for in-patient students. The findings I have gained from integrating art affirm my position on art as a universal language. Art is considered as a universal language that has a broad spectrum of manifestations to meet the skills and interest of anyone. Ernst Kris was a psychologist and art historian, known for his psychoanalytic studies of artistic creation and for combining psychoanalysis and direct observation of children in child psychology. In 1952he wrote that “the study of art is part of the study of communication, because there is always a sender, a receiver and a message”.

Kris added: “Painting is expressed through its composition and colors. The content of the work is the message you are trying to convey. Art, in the case of painting, is a type of non-verbal communication, which despite not being as clear as the verbal, communicates something. All forms of communication consist of at least two fundamental components, in the case of painting, including four: (1) the sender, in this case, the artist, who in painting tries to transmit and / or communicate through colors something; (2) the message, which is the work, its composition, are the ideas it tries to convey; (3) the recipient, who is the person who receives the message; and (4) the viewer, who is the absent object, is the theme, motive, or source of inspiration.

Other authors have considered art as an alternative means to achieve communication. [11], for example, tell us that art has the advantage of providing a means to express and communicate beliefs and feelings that the person may find difficult to express. It can be understood as a more private perception of your feelings. Also[12], professor of art psychology says that images, drawings, and paintings optically reproduce perceptions. Furthermore, the true value of images lies in the ability to transmit information that cannot be encoded in any other way. In the same way [13] expresses it in his book: “each art speaks a language that transmits what cannot be said in another language, what cannot be fully expressed - it gathers the feeling that another language cannot collect. In this sense, the importance that the transmitter can fully express so that the receiver can understand is valued and known.” Therefore, art can be a viable medium for other possibilities besides communication. Artistic creation is not only an act of expression of a feeling, it is also a way for motivation, a way of working awareness, a way to acquire new knowledge and attitudes, and a form of communication [14]. Given that art is a creative and motivational mode of expression, it is justified to explore this strategy as a means of communication for the Deaf population, within the framework of action research.

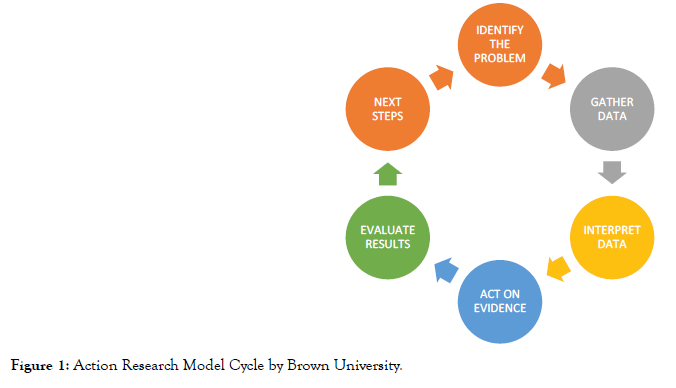

This action research follows Ferrance model [15] (Figure 1). This model has five steps of continuous research. (1)identify the problem, (2)collect and organize the data, (3) interpret the data, (4) action based on the data, and (5) mirror. The figure shows the action research model (Figure 1). Data collection utilized a phenomenological approach to explore and describe a social phenomenon, for which there is not enough information. Based on Husserl, phenomenology, as explained by [16], describes a phenomenon as lived by the participant. In accordance with [17], phenomenology studies the structure of various types of experience ranging from perception, thought, memory, imagination, emotion, desire, and volition to bodily awareness, embodied action, and social activity, including linguistic activity.

Figure 1. Action Research Model Cycle by Brown University.

In this case the phenomenon was the socioemotional burden suffered by Deaf students when hurricane María stroke Puerto Rico in 2017. It describes the psychological burden that many students and adults from the Deaf community in Puerto Rico still have after two years of the Hurricane. This action research aims to present a strategy that I designed using art as an alternative means for Deaf students to communicate their feelings and to foster rewriting skills.

A total of five students with deafness participated in this study during a two-year period. Protocols were followed when conducting human research. The students and their parents received information on the case study and signed a consent form to participate in each intervention. They also accepted to make the findings public since the participants names does not appear. The IRB allows investigations and case studies under the university courses. An investigation can take place taking into consideration confidentiality and informed consent, among others. Furthermore, the study was carried out under the supervision of the professor of the courses. For the sampling method, I spoke to the parents of my Deaf students about the investigation and the participants were selected according to their availability. This sample does not represent the entire school population that receives services in regular schools from the Department of Education in Puerto Rico.

I worked individually with each participant in school. They were given identification in order to protect their identity. In Table 1 there is a summary of their demographic data. After explaining, orally and in sign language, the purpose of the study, I used photos published in various newspapers in Puerto Rico after the hurricane to help the participants remember the event. Then he/she was asked to make drawings based on the following two questions: (1) how you felt when it happened? and (2) what impacted you the most? After the participants finished the drawing, I asked them to explain what those drawing meant to them. I took notes on their responses. The participants parents/guardians were informed about the findings (Figure:1).

| Participant - ID | Gender | Age | Type of hearing loss | Communication mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP001 | Male | 10 | Mild (26-40 dB HL) |

Oral |

| YJ002 | Female | 21 | Moderately Severe (56-70fB HL) |

Oral and sign language |

| DS003 | Male | 8 | Profound (91 dB HL +) |

Sign language |

| GR004 | Male | 12 | Moderate (41-55 dB HL) |

Oral and sign language |

| BL005 | Male | 17 | Mild (26-40 dB HL) |

oral |

Table 1: Participants.

Identification of the problem

After a month of hurricane María, I approached my friends from the community of Deaf adults, and when they mentioned me how was their experience during the hurricane, as a teacher, I got worried for my students. I identified the problem and developed a three-stage-intervention strategy to help Deaf students communicate what they felt, or still feel after this natural disaster. The first stage is to establish rapport. Getting to know the student could provide a more comfortable experience, identify his or her prefer mode of communication (oral, sign language, other), and it will give you tips of possible interest that can be used for further data gathering. In this stage, I explained to each participant the activity. The second stage is about giving the participant a choice. Present various art materials (play-do, paint, colored pencils, colored paper, white paper, music instruments, others) on a table so he or she can select the art material to carry out the activity. In my case, the participants chose paint and charcoal pencil to draw. In this second stage, I presented a short story, pictures, and video clips to stimulate dialogue, followed by asking them to draw or paint to answer the two main questions: (1) how you felt when it happened? and (2) what impacted you the most? The third and last stage was to reflect and think over what they drew or painted, explaining their paintings and drawings. I asked some questions when necessary in order to understand better.

Data gathering

The data was collected during three periods: (1) two months after hurricane María in November 2017, (2) a year after hurricane María, and (3) two years after the hurricane. For each period, I used a different approach. In the first period, and after explaining the purpose of the activity and getting their consent, I presented three published media pictures about hurricane. Picture #1 was of a woman dragging a small suitcase through a broken road. Picture #2was of houses without roofs and families climbing in the remains of the house due to flooding, including children and dogs. Picture #3, showed a street destroyed with a serious natural deforestation. During the second period in September 2018, I used a short story on the topic of a hurricane. The short story was Germancito the Hermit Crab, a short story published by the Federal Emergency Management Administration, FEMA, where “Germancito”, a crab, lost his shell due to a hurricane. To help with the comprehension I asked questions about the book before, during, and after reading the book. Questions before, were to activate their prior knowledge. During the reading, the questions were to develop comprehension and provide time for them to express their opinion. And after reading, the questions aim to give an opportunity to comment. At this moment, the students started answering comprehension questions with drawings until he or she achieve a pre-writing stage.

For the third and last intervention, I played a news video where Puerto Rico is presented flooded with most of the roads destroyed and many houses without roofs. The activities for this third intervention were done on September 2019. “Some studies have shown that deaf people have visuospatial advantages” [18] After watching a news video from YouTube, I provided the opportunity for the participants to comment about it. Then, I asked them to paint their feelings based on the two main questions mentioned before.

Interpretation of data

The results of this action research are presented in the sequence of the interventions. Their drawings and or paintings are included with their responses to the questions posed. A brief interpretation of the psychologist is also included.

Intervention #1

Student id: NP001

Date: November 17, 2017

Items used: Published media pictures about hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Question #1:How did you feel?

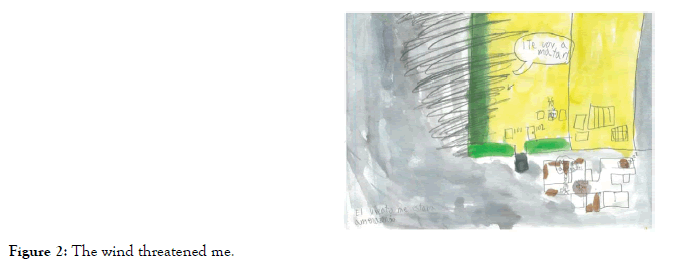

Painting #1:"The wind threatened me!" (Figure:2)

Figure 2. The wind threatened me.

In his first drawing, NP001 drew a building. He drew it from the inside, and from the outside. Next to the building he drew a moving hurricane. On the inside of the building, he drew himself, his grandmother, and his pet dog, Jupiter. The background of the drawing is dark, and he only painted with brown color his grandmother and his pet, he preferred not to paint himself and leave it blank, in charcoal pencil. Then he wrote on the bottom right side of the paper that the wind was threatening him. After reading what he wrote, I said: "Oh, you felt threatened by the wind", to which he replied “no, the wind threatened me”. Both are not the same. I asked about the person who had the “zZz’s” on the head and he explained that it was his grandmother who slept during the whole hurricane. Dr. Muriel, the psychologist, interpreted the black background as a signal of fear and loneliness. The swirls and size of the hurricane indicate distress and a possible mild disorder in his mental health. He explained that the hurricane and the wind were so strong that NP001gave him “life”, in such a way that it threatened him.

Question #2: What happened to you that impacted you the most?

Painting #2:"Windows” (Figure:3)

Figure 3. Windows.

To answer the second question, NP001 drew windows representing the most shocking moment he went through. The kitchen windows, which are made of wood, were opened by the strong wind. The background, which can be thought as the wall of the house, has brown lines. I asked about the walls, but NP001 said that he wanted to do one more painting, “the walls are not important.” He mentioned that the rest of the windows, which were not in wood, vibrated more than a horn. And when he explained to me the painting he expressed: “Suddenly the wind opened the kitchen windows that are made of wood. I thought he (the wind) was going to take me there "..." I had to close them by myself, I felt like a super hero, like Spiderman, because it was difficult for me, but I did it." Once again Dr. Muriel emphasizes the possible mental disorder NP001 presents in his paintings.

In another painting, NP001 drew one of the newspaper photos that I presented him. He chose the image where the road no longer existed. His painting was very similar to the original photo; instead, he painted blurred mountains. When he finished his drawing, he commented to me: “This is how it looked when the wind opened the windows. Just like that picture. I was scared; it looked like The Walking Dead” (Figure: 4).

Figure 4. The Walking Dead.

Student id: YJ002

Date: November 21, 2017

Type of approach: Published media pictures about hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Question #1:How did you feel?

Painting #1& #1.2:“Alone”

YJ002 decided to do two paintings to express how she felt physically and mentally during the hurricane (Figure: 5).

Figure 5. Alone.

In this painting, she drew a face of pain and behind her was hurricane María lifting the roof of a house. She later explained that even though she is Deaf, she could hear and feel the wind against the house ceiling. Although the hurricane did not take the roof of her house, this is how she felt. She drew palms that reclined to the right side in the wind. She commented that, physically, she felt bad. Her massive nerves gave her a stomachache.

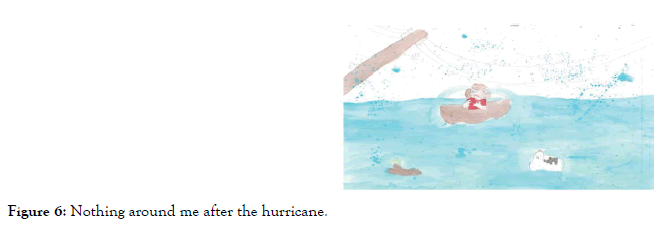

In the second painting YJ002 made to answer the first question, she made a painting of how she felt mentally. She drew herself surrounded by water while she was in a small boat, with nothing else around, just her pet, a dog that was floating on her bed, and a fallen electricity pole. For this drawing she commented the following: “I felt without strength. I felt like I was going to drown and that I was surrounded by water. It was like there would be nothing around me after the hurricane” (Figure: 6).

Figure 6. Nothing around me after the hurricane.

Question #2: What happened to you that impacted you the most?

Painting #2:"Windows” (Figure:7)

Figure 7. Windows.

YJ002 drew herself in the interior of her house. She drew a broken window, an upside-down sofa, and herself trying to close a door. She explained that she, her family, and neighbors had to go outside to uncover the sewers. It was a matter of time for all the houses got flooded. After uncovering the sewers, YJ002 and her family rushed back inside of the house, but they could not close the door because of the wind. It took five people (all the family) to close the door. YJ002 expressed that even though she knew her siblings and parents where closing the door with her, she felt she was closing it without help due to the strength she had to use. She even had to put her foot on the wall in order to close the door.

Dr. Muriel, the psychologist, analyzed the three paintings and her explanation of each. He understands that YJ002 had a moment of relief while painting. He added: “Painting gave her the opportunity to “get out” of her system everything that had her anxious. The way she painted and what she communicated about these paintings could be signs of anxiety that started with hurricane María and continue after the hurricane due to her repressed feelings.”

With these findings, is clear that both participants had not had the opportunity to reflect on the damage caused to them by the hurricane. NP001 expressed in his drawings that the experience of Hurricane María affected him in such a way that he thought that the hurricane wanted to kill him. YJ002 expressed that she felt she was drowning and that she was the only thing left of everything she owned. A year after Hurricane María, I asked YJ002, at that moment 22 years old, how she felt a year after the hurricane. Summarizing our conversation, she told me that when it rains and /or thunders, she becomes anxious and her digestive system is altered.

Intervention #2

After reading the short story book, I asked the student, DS003, if he has experienced a hurricane. He answered signing the word “hurricane” and spelling “María”. I also asked them to main questions about the hurricane. He decided to answer both questions in one drawing.

Student id: DS003

Date: September 13, 2018

Type of approach: Story book

Questions: (1) How did you feel? and (2) what happened to you that impacted you the most?

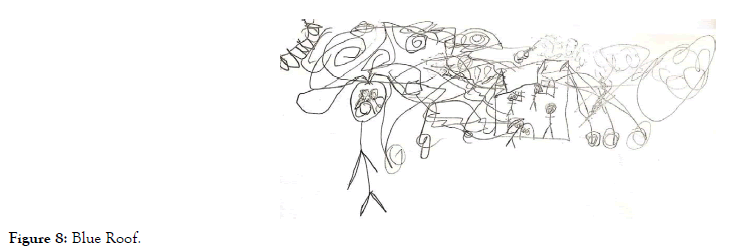

Painting: “Blue Roof” (Figure:8)

Figure 8. Blue Roof.

DS003 drew himself with his family outside of the house during the hurricane. Compared to his family, DS003 drew himself apart, bigger than his family, accompanied with big tears on his face. I asked him about details in his drawings. He explained that his family and he had to step out of the house to put the “blue ceiling” (tent) on their roof. He could not see the sun, but wished it were there, because outside he felt cold. That is why he drew the sun. This moment, for DS003, was one that marked his life, because he said that he still re-lives it as a memory when it pours rain in Puerto Rico.

The swirls that are not clouds are the heavy wind he felt, and the long lines with circles at the end are ropes that hold the houses “new blue roof”. DS003, who is now learning sign language, signed that he felt sad, cold, and lonely since his family does not know sign language, or at least the words he knows. Following a written first word besides his name: “cold”.

Intervention #3

Student id: GR004

Date: September 19, 2019

Type of approach: News video about after hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Question #1: How did you feel?

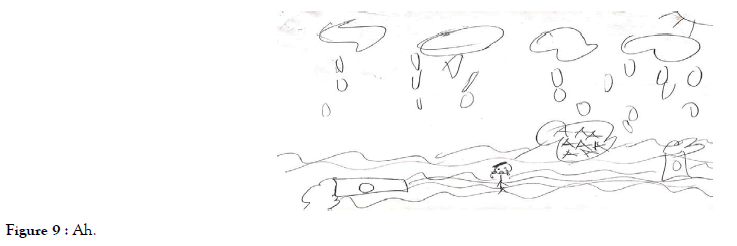

Painting: “Ah!” (Figure: 9)

Figure 9. Ah.

GR004 drew himself in a water stream, clouds on top with pouring rain and two trees that the wind took down. He also drew a comment bubble that said “Ah!” and a sun on the top right. I asked him if he went outside of his house during the hurricane and he answered that he did not. When I asked him why he was surrounded by a body of water he expressed: “So much water came in that I felt like I was in the river that’s behind my house. The water was up to my knees, I wanted to scream, because it was a lot and cold, but I knew I should not worry my parents.” I also asked about the sun he drew, since there was no sun during the hurricane. He answered that sun was needed that day and since it was his drawing, he drew a sun because he still thought it was needed. What Dr. Muriel finds interesting about this drawing and about the drawing done by DS003 is that both drew a Sun, and both expressed that they felt cold due to the absence of it.

Student id: GR004

Date: September 19, 2019

Type of approach: News video about after hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Question #2: What happened to you that impacted you the most?

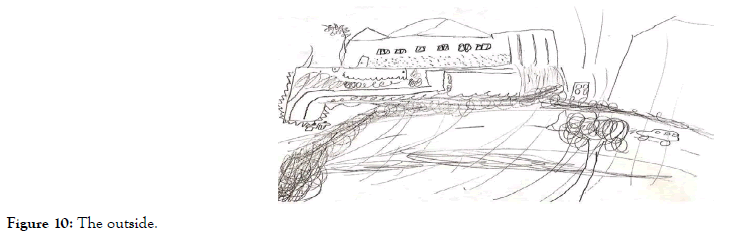

Painting: “The outside” (Figure: 10)

Figure 10. The outside.

GR004 took more time to do this second drawing. If both drawings are side by side, you can see that he took his time to draw every little detail. I asked him why he spent more time drawing the second one and he answered that he needed to let others see exactly what he saw. “It was a sad and grey day. I still remember the crowdedness of everything and the brown colored river that covered the streets.

Student id: BL005

Date: September 19, 2019

Type of approach: News video about after hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Question #1: How did you feel?

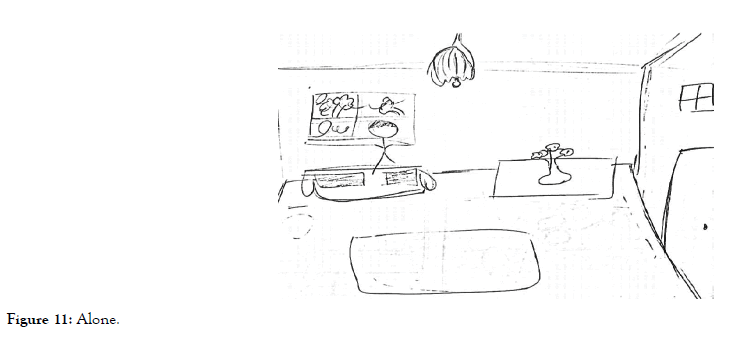

Painting: “Alone” (Figure:11)

Figure 11. Alone.

BL005 drew himself standing on his knees on his living room sofa looking out the window. He expressed that he was not good at drawing, but that he thought it was a good idea to discuss this situation. He remembers and expressed orally: “I heard a lot of noise; I had never heard the wind so loud. I took off my headphones and it was a vacuum. I felt like I was alone at that moment. I remember that I knelt on the sofa at home to look out the window. I was calm, but what I saw through the window was unbelievable. There was nothing, trees covered the floor. I didn't think the wind could do that.”

Student id: BL005

Date: September 19, 2019

Type of approach: News video about after hurricane María in Puerto Rico

Question #2:What happened to you that impacted you the most?

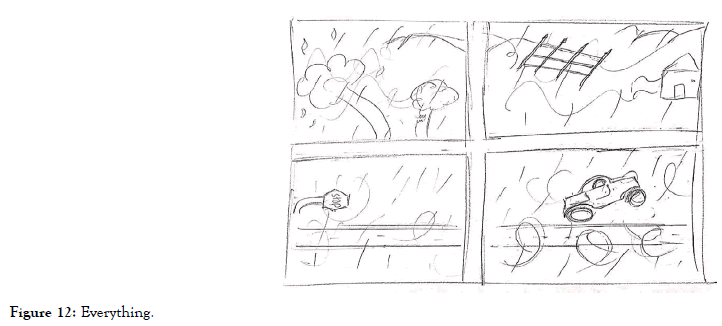

Painting: “Everything” (Figure:12)

Figure 12. Everything.

While drawing, BL005 commented that this activity was the only time he spoke about that day and his feelings. He had spoken with his friends about what they saw, but not about how they felt. He drew a window where you could see the outside. BL005 drew four different images in one drawing. He then said “there were heavy bars flying. The neighbor's car was moving with the wind. There were signs folded and on the floor. The trees lost their leaves, a trunk was almost black and as if splitting from as strong as the wind was.”

Act on evidence

The evidence of my action research as a teacher of the Deaf ,allow me to re-exam the strategy to act upon those needs of the Deaf students that are not identified in a general education curriculum or in the training of professionals who work with this population. Both the results and the design of the three-stage strategy that I used with the five participants could be used by to address emotional needs of Deaf students and adults. Thus, my goal is to share this strategy with other teachers and professionals that work with Deaf people. In addition of writing this article, later I plan to share the strategy on the web to outreach more professionals in the field of deafness. Teachers and other special lists should acknowledge the emotional needs of Deaf students and adults after traumatic events and be able to assist them in communicating those worries and fears.

The drawings and painting of these participants is a sample of the emotional needs that Deaf people have after a natural disaster like a hurricane. The lack of oral or sign skills to communicate their emotional needs seems to be a great challenge faced by the Deaf community in Puerto Rico. They are invisible to those planning and providing services after a natural disaster.

It is necessary to provide an alternative means of communication to Deaf people to express their feelings, especially after a traumatic event. Muriel, the psychologist who evaluated the drawings, suggested that some elements of the painting and drawings showed fear, insecurity, and anxiety. Almost all participants drew themselves alone during the event, even when they live with their families. It was also evident that a “one shot” aid is not enough to support the emotional needs of Deaf people.

From a teacher perspective, the use of drawings and paintings serve to facilitate dialogs with our students in the affective domain that are not addressed in a language curriculum. Photo or video clips on traumatic events have the potential to elicit that our Deaf students communicate with draw and paints about their fears and worries. Drawings and painting could serve as a scaffold to encourage them to start writing (one-word stage), about their fear or feelings. After using these strategies, one should follow up. One intervention is not enough. Another recommendation is to give the Deaf adult community the opportunity to share their traumatic experiences with our students. This empathic experience has the potential to support Deaf students’ emotions and to understand that is ok to share their feelings with others. In addition, our students will have the opportunity to learn the signs to express feelings and to feel that they are not alone.

Although this action research was carried out in Puerto Rico, the strategy tested could be used with other Hispanic Deaf children in any other country, because natural disasters could trigger fear and distress anywhere.

Received: 02-May-2020 Accepted: 05-Jun-2020 Published: 12-Jun-2020 , DOI: 10.35248/2375-4427.20.8.195

Copyright: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.