Family Medicine & Medical Science Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2327-4972

ISSN: 2327-4972

Research Article - (2020)Volume 9, Issue 3

Background: Despite the improvement in healthcare services provided for mentally-ill individuals, yet they often choose not to seek such care or stop taking their medicines due to the surrounding stigma. Many tools in the last years have been developed to assess stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental illness.

Objectives: To assess public attitude towards mental disorders in Egypt and its association with their sociodemographic characteristics. Subjects and Methods: This is a cross-sectional study conducted at the Family Medicine outpatient clinic of Suez Canal University Hospital, Ismailia, Egypt. Two hundred and fifteen participants were interviewed and requested to fill in three questionnaires; demographic questionnaire, socioeconomic status questionnaire, and Attitude to Mental Illness questionnaire. Results: Participants had negative attitudes concerning the fear and exclusion of people with mental illness (19.03 ± 3.86 points). However, they had more positive attitude towards causes of mental illness and the need for special services (11.14 ± 2.02 points), integrating people with mental illness into the community (25.02 ± 4.09 points), understanding and tolerance of mental illness (27.38 ± 3.41 points).

Conclusion: Public attitude towards mental illness can be variable. Although the attitudes regarding their fear and exclusion of patients with mental illness were negative; however, we found a huge understanding and tolerance towards mental illness and supported integrating patients with mental illness into the community. Recommendation: Anti-stigma programs are needed to boost people's acceptance of mental illness and strategies to increase social contact of the public with mentally-ill should be considered.

Attitudes, Mental illness, Public

Mental illnesses have been receiving increasing attention from the science community during the past decades due to the burden they pose on people's lives. In Egypt, almost one-fifth of the adult population struggle with mental illness [1]. And despite the improvement in healthcare services provided for mentallyill individuals, yet they often choose not to seek such care or stop taking their medicines. One of the most important reasons behind this reluctance to seek support and treatment is the stigma mentally-ill people have to face every day (2). Stigma is a negative label frequently attached to persons who deviate from social norms in some aspects, such as mental health [3]. People with mental illness face difficulties in social relationships, experience social isolation and withdrawal, homelessness and unemployment [2,4].

Moreover, one in four families has at least one member struggling with a mental or behavioral disorder. These families are expected to provide physical and emotional support for their member, and also bear the negative impact of the disease, ranging from the economic and emotional difficulties, the stress of coping with this disturbed behavior, the disruption of household routine and the restriction of social activities [5]. Therefore, mental illness stigma hurts mentallyill individuals and their families and sadly, it will sometimes lead to very devastating consequences [2], and thus, many tools in the last years have been developed to assess stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental illness [6].

Considering the increasing prevalence of mental illness worldwide and the high burden of the disease in Egypt, we conducted this study in order to assess the public attitude towards mental illnesses and the impact of their socio-demographic characteristics on this attitude.

This is a cross-sectional study conducted at the Family Medicine outpatient clinic of Suez Canal University Hospital, Ismailia, Egypt from July 2018 to October 2018. The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University before commencement and informed consents were obtained from each participant before their enrollment. Two hundred and fifteen participants met our selection criteria and were selected by a convenience sampling technique from the adult population attending the outpatient clinic at SCU hospital. Meanwhile, patients of mental illnesses or those using any medications that might cause depression as a side effect were excluded.

Study Procedure

Every participant was interviewed in order to fill in three questionnaires; demographic questionnaire, socioeconomic status (SES) questionnaire, and Attitude to Mental Illness questionnaire. The demographic questionnaire surveyed data related to the participant's age, gender, marital status. Then participant's SES was assessed using the modified scoring system of Fahmy and El- Sherbini for measurement of SES in health research in Egypt [7]. It consists of 7 domains with a total score of 84. The final scores were categorized into very low, low, middle, and high.

Finally, the participant's attitude towards mental illness was evaluated by Attitudes to Mental Illness questionnaire [8]. The questionnaire included a number of statements about mental illness. Participants were asked to indicate how much they agreed or disagreed with each statement through a 5-point Likert scale. The questions also included other aspects such as descriptions of people with mental illness and the participant's relationships with them, personal experience of mental illness, and perceptions of mental health-related stigma and discrimination. The questionnaire was translated into Arabic language by a certified translation office without any alteration or loss of its concepts. The translated version of the questionnaire was examined for accuracy and piloted to assure its clarity.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (SPSS), 23rd edition. Continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical data as percentage. T-test was used to compare between quantitative, while Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used to to find the relations between adult attitudes toward mentally ill patients versus different demographic characteristics of the participants. Results were considered statistically significant at a p-value of less than 0.05.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the studied group. Mean age of participants was 47±13.4 years. They were predominantly females (71.6%), housewives or unemployed (67.4%), lived in urban areas (85.6%), and were of low socioeconomic status (58.6%). About 40% of the participants were illiterate and those who only can read and write formed 20%. About half of the participants were only able to meet their routine expenses. Regarding health care, 38.1% of them had an access to more than one health care facility and 27% had an access to private health facilities. A total of (n=10,223) married women were interviewed in 2016 EDHS. Among these married women 4451 (43.54%) were within the age group of 25-34 years. The mean age of the respondents was 27 years (SD ± 9 years). More than half of the respondent 6253 (61.2%) were not educated. About 3,401 (33.26%) of respondents had more than four children and large proportion of respondents 7400 (72.39%) had cohabitation before age of 18 years. Regarding to partner’s education level, 4,685 (45.82%) were not educated (Table 1).

| Variables | n = 215 |

| Age (years), Mean ± SD | |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 61 (28.4) |

| Female | 154 (71.6) |

| Residence, n (%) | |

| Rural | 184 (85.6) |

| Urban slum | 26 (12.1) |

| Urban | 4 (1.9) |

| Occupation, n (%) | |

| Housewife/ unemployed | 145 (67.4) |

| Unskilled manual work | 21 (9.8) |

| Skilled manual work | 10 (4.7) |

| Trades | 9 (4.2) |

| Semiprofessional/clerk | 28 (13) |

| Professional | 2 (0.9) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Illiterate | 84 (39.1) |

| Read and write | 43 (20) |

| Primary school | 29 (13.5) |

| Secondary | 29 (13.5) |

| Intermediate | 17 (7.9) |

| Graduate | 10 (4.7) |

| Postgraduate | 3 (1.4) |

| Economy, n (%) | |

| In debt | 60 (27.9) |

| Just meet routine expenses | 105 (48.8) |

| Meet routine expenses and emergencies | 35 (16.3) |

| Able to save/invest | 15 (7) |

| Health care, n (%) | |

| More than one source | 82 (38.1) |

| Free governmental health services | 57 (26.5) |

| Health insurance | 18 (8.4) |

| Private health facilities | 58 (27) |

| Crowing index | |

| ≤ 1 person per room | 105 (48.8) |

| > 1 person per room | 110 (51.2) |

| Family Equipment | |

| < 5 equipment | 78 (36.3) |

| ≥ 5 equipment | 137 (63.7) |

| Socioeconomic status category | |

| Very low | 43 (20) |

| Low | 126 (58.6) |

| Middle | 40 (18.6) |

| High | 6 (2.8) |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the studied sample.

Table 2 shows adult attitude towards mental illness. Regarding fear and exclusion of people with mental illness, the overall total score for this domain was 19.03 ± 3.86 points, which points out to the negative attitude of the participants concerning that domain. Statements 3, 15 and 18 had the highest percent of agreeing in that domain (95%, 92.6% and 93%, respectively), which reflects high negative attitudes. Meanwhile, as for their understanding and tolerance of mental illness, the overall total score for that domain was 27.38 ± 3.41 points, reflecting positive attitudes. Statements 9, 10 and 23 had the highest percentage of agreeing (89%, 92% and 94% respectively). However, statement 11 and 13 showed a high percent of disagreeing (92% and 91%, respectively), which all reflects a positive attitude towards mental illness concerning that domain.

| Statement | Mean ± SD | Agree (%) | Disagree (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear and Exclusion of People with Mental Illness | |||||

| . As soon as a person shows signs of mental disturbance, he should be hospitalized | 2.57 ± 0.68 | 204 (94.9) | 11(5.1) | ||

| . People with mental illness are a burden on society | 3.28 ± 0.15 | 113 (52.6) | 102 (47.4) | ||

| . People with mental illness should not be given any responsibility | 1.21 ± 0.97 | 16 (92.6) | 199 (7.4) | ||

| . A woman would be foolish to marry a man who has suffered from mental illness, even though he seems fully recovered | 2.39 ± 1.32 | 51 (76.3) | 164 (23.7) | ||

| . I would not want to live next door to someone who has been mentally | 2.33 ± 1.14 | 36 (16.7) | 179 (83.3) | ||

| . Anyone with a history of mental problems should be excluded from taking public office | 1.94 ± 0.91 | 14 (93.5) | 201 (6.5) | ||

| . It is frightening to think of people with mental problems living in residential neighborhoods | 2.13 ± 0.99 | 87 (40.5) | 128 (59.5) | ||

| . Locating mental health facilities in a residential area downgrades the neighborhoods | 3.16 ± 1.03 | 96 (44.7) | 119 (55.3) | ||

| Total | 19.03 ± 3.86 | ||||

| Understanding and Tolerance of Mental Illness | |||||

| . Virtually anyone can become mentally ill | 2.40 ± 1.13 | 53 (24.7) | 162 (75.3) | ||

| . People with mental illness have for too long time been the subject of ridicule | 3.31 ± 1.36 | 124 (57.7) | 91 (42.3) | ||

| . We need to adopt a far more tolerant attitude toward people with mental illness in our society | 4.22 ± 0.77 | 192 (89.3) | 23 (10.7) | ||

| . We have a responsibility to provide the best possible care for people with mental illness | 4.43 ± 0.82 | 198 (92.1) | 17 (7.9) | ||

| . People with mental illness don’t deserve our sympathy | 4.35 ± 0.85 | 199 (7.4) | 16 (92.6) | ||

| . Increased spending on mental health services is a waste of money | 4.37 ± 0.83 | 197 (8.4) | 18 (91.6) | ||

| . As far as possible, mental health services should be provided through community-based facilities | 4.30 ± 0.65 | 203 (94.4) | 12 (5.6) | ||

| Total | 27.38 ± 3.41 | ||||

| Causes of Mental Illness and the Need for Special Services | |||||

| . One of the main causes of mental illness is a lack of self-discipline and willpower | 3.69 ± 1.06 | 129 (60.0) | 86 (40.0) | ||

| . There is something about people with mental illness that makes it easy to tell them from normal people | 4.07 ± 0.90 | 184 (85.6) | 31 (14.4) | ||

| . There are sufficient existing services for people with mental illness | 3.39 ± 1.01 | 124 (57.7) | 91 (42.3) | ||

| Total | 11.14 ± 2.02 | ||||

| Integrating People with Mental Illness into the Community | |||||

| . Mental illness is an illness like any other | 3.92 ± 1.15 | 166 (77.2) | 49 (22.8) | ||

| . Less emphasis should be placed on protecting the public from people with mental illness | 3.08 ± 1.27 | 105 (48.8) | 110 (51.2) | ||

| . Mental hospitals are an outdated means of treating people with mental illness | 2.58 ± 1.05 | 52 (24.2) | 163 (75.8) | ||

| . No one has the right to exclude people with mental illness from their neighborhoods | 3.71 ± 1.30 | 143 (66.5) | 72 (33.5) | ||

| . People with mental illness are far less of a danger than most people suppose | 3.07 ± 1.06 | 98 (45.6) | 117 (54.4) | ||

| . Most women who were once patients in a mental hospital can be trusted as babysitters | 1.78 ± 0.97 | 19 (8.8) | 196 (91.2) | ||

| . The best therapy for many people with mental illness is to be part of a normal community | 3.91 ± 1.12 | 165 (76.7) | 50 (23.3) | ||

| . Residents have nothing to fear from people coming into their neighborhoods to obtain mental health services | 3.61 ± 0.87 | 139 (64.7) | 76 (35.3) | ||

| . People with mental health problems should have the same rights to a job as anyone else | 3.08 ± 1.15 | 93 (43.3) | 122 (56.7) | ||

Table 2: Adult attitude towards mental illness (n=215).

Regarding the participants' attitude towards the causes of mental illness and the need for special services, the overall total score for that domain was 11.14 ± 2.02 points; thus, participants had positive thoughts regarding the causes of mental illness and the need for special services. Statement 2 had the highest scores in that domain with mean scores 4.07 ± 0.90 points with a percentage of agreeing 85.6% reflecting a positive attitude. Finally, regarding integrating people with mental illness into the community, the overall total score for that domain was 25.02 ± 4.09 points; therefore, participants supported integrating people with mental illness into the community. Statements 4, 22 and 19 had the highest scores in that domain with mean scores 3.92 ± 1.15, 3.91 ± 1.12 and 3.71 ± 1.30 points, respectively and percentage of agreeing 77.2%, 76.7% and 66.5%.

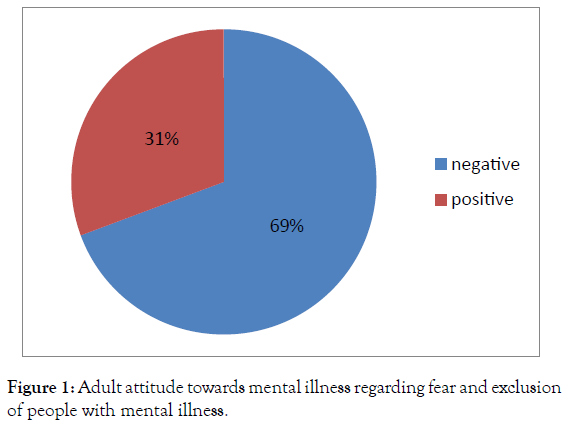

Regarding fear and exclusion of people with mental illness, 69% of the participants expressed negative attitudes, while only 31% were positive one (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Surgical training questionnaire

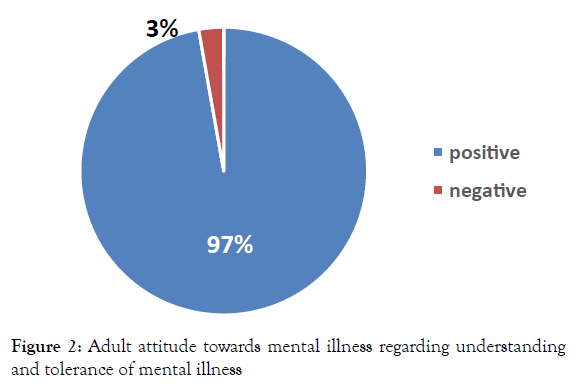

Almost all the participants (97%) had a positive attitude concerning understanding and tolerance of mental illness (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Surgical training questionnaire

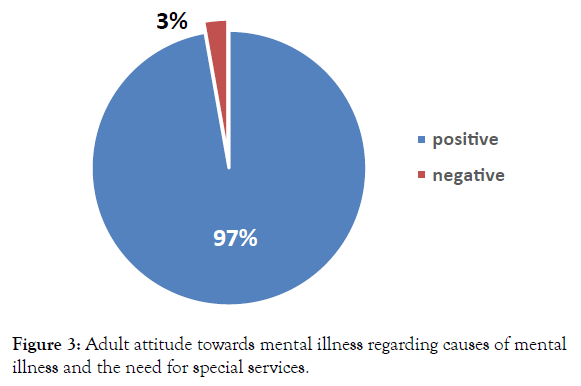

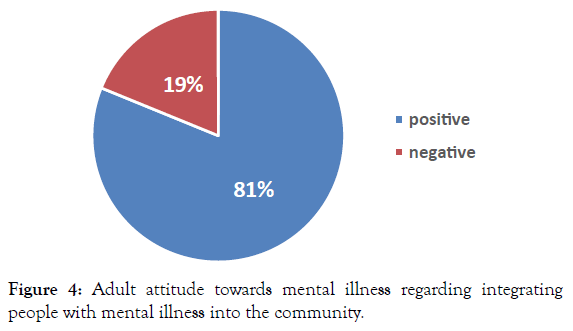

Figure 3 shows adult attitude towards mental illness regarding causes of mental illness and the need for special services, where 97% of the participants showed positive attitudes.The majority of the participants (81%) had positive attitudes concerning integrating people with mental illness into the community.

Figure 3. Adult attitude towards mental illness regarding causes of mental illness and the need for special services.

Figure 4. Adult attitude towards mental illness regarding integrating people with mental illness into the community.

Table 3 shows the relationship between adult attitude regarding fear and exclusion of mental illness domain and their sociodemographic characteristics. We found that those with a low crowding index had significantly more positive attitude than those with a high crowding index (p=0.023). Moreover, participants with a higher socioeconomic status had significantly more positive attitude than those with lower ones (p=0.041).Regarding understanding and tolerance of mental illness and its association to their socio-demographic characteristics, we found that those in debt had significantly more negative attitudes than those with better financial status (p=0.048) (Table 4).

| Variables | Attitude | Test-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | |||

| (n= 149) | (n= 66) | |||

| Age (years), Mean ± SD | 42.09 ± 13.11 | 44.45 ± 11.83 | -1.525a | 0.21 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 49 (32.9) | 12 (18.2) | 4.86c | 0.033* |

| Female | 100 (67.1) | 54 (81.8) | ||

| Occupation, n (%) | 96 (64.4) | 49 (74.2) | ||

| Housewife | 15 (10.1) | 6 (9.1) | ||

| Unskilled manual work | 8 (5.4) | 2 (3) | ||

| Skilled manual work | 7 (4.7) | 2 (3) | ||

| Trades | 21 (15.4) | 7 (10.6) | ||

| Semiprofessional/clerk | 2 (1.3) | 0 | ||

| Professional | 2.14c | 0.852 | ||

| Education, n (%) | 32 (48.5) | |||

| Illiterate | 52 (34.9) | 14 (21.2) | 9.79c | 0.117 |

| Read and write | 29 (19.5) | 10 (15.2) | ||

| Primary school | 19 (12.8) | 7 (10.6) | ||

| Secondary | 22 (14.8) | 3 (4.5) | ||

| Intermediate | 14 (9.4) | 0 | ||

| Graduate | 10 (6.7) | 0 | ||

| Postgraduate | 3 (2) | |||

| Economy, n (%) | ||||

| In debt | 34 (22.8) | 26 (39.4) | 6.25c | 0.097 |

| Just meet routine expenses | 78 (52.3) | 27 (40.9) | ||

| Meet routine expenses and emergencies | 25 (16.8) | 10 (15.2) | ||

| Able to save/invest | 12 (8.1) | 3 (4.5) | ||

| Health care, n (%) | ||||

| More than one source | 60 (40.3) | 22 (33.3) | 4.77b | 0.19 |

| Free governmental health services | 33 (22.1) | 24 (36.4) | ||

| Health insurance | 13 (8.7) | 5 (7.6) | ||

| Private health facilities | 43 (28.9) | 15 (22.7) | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | 125 (83.9) | 59 (89.4) | 2.08c | 0.393 |

| Urban Slum | 19 (12.8) | 7 (10.6) | ||

| Urban | 5 (3.4) | 0 | ||

| Crowding index | ||||

| ≤ 1 person per room | 80 (53.7) | 25 (37.9) | 4.58b | 0.023* |

| > 1 person per room | 6 (46.3) | 41 (62.1) | ||

| Family Equipment | ||||

| < 5 equipment | 52 (34.9) | 26 (39.4) | 0.4b | 0.542 |

| ≥ 5 equipment | 97 (65.1) | 40 (60.6) | ||

| Socioeconomic status category | ||||

| Very low | 35 (23.5) | 8 (12.1) | 7.98c | 0.041* |

| Low | 79 (53) | 47 (71.2) | ||

| Middle | 29 (19.5) | 11 (16.7) | ||

| High | 6 (4) | 0 | ||

Table 3: Association between adult attitude regarding fear and exclusion of people with mental illness subscale and their socioeconomic characteristics.

| Variables | Attitude | Test-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n=209) |

Negative (n=6) |

|||

| Age (years), Mean ± SD | 43.02 ± 12.85 | 45.67 ± 11.51 | -1.51a | 0.13 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 61 (29.2) | 0 | 2.45b | 0.187 |

| Female | 148 (70.8) | 6 (100) | ||

| Occupation, n (%) | ||||

| Housewife | 139 (6.5) | 6 (100) | 2.47b | 0.891 |

| Unskilled manual work | 21 (10) | 0 (0) | ||

| Skilled manual work | 10 (4.8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Trades | 9 (4.3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Semiprofessional/clerk | 28 (13.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Professional | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| Illiterate | 79 (37.8) | 5 (83.3) | 3.961b | 0.69 |

| Read and write | 42 (20.1) | 1 (16.7) | ||

| Primary school | 29 (13.9) | 0 (0) | ||

| Secondary | 29 (13.9) | 0 (0) | ||

| Intermediate | 17 (8.1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Graduate | 10 (4.8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Postgraduate | 3 (1.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Economy, n (%) | ||||

| In debt | 55 (26.3) | 5 (83.3) | 6.48b | 0.048* |

| Just meet routine expenses | 104 (49.8) | 1 (16.7) | ||

| Meet routine expenses and emergencies | 35 (16.7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Able to save/invest | 15 (7.2) | 0 (0) | ||

| Health care, n (%) | ||||

| More than one source | 78 (37.3) | 4 (66.7) | 2.93b | 0.423 |

| Free governmental health services | 55 (26.3) | 2 (33.3) | ||

| Health insurance | 18 (8.6) | 0 (0) | ||

| Private health facilities | 58 (27.8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | 178 (85.2) | 6 (100) | 0.72b | 0.9 |

| Urban slum | 26 (12.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Urban | 5 (2.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Crowing index | ||||

| ≤ 1 person per room | 102 (48.8) | 3 (50) | 0.003b | 0.9 |

| > 1 person per room | 107 (51.2) | 3 (50) | ||

| Family Equipment | ||||

| < 5 equipment | 74 (35.4) | 4 (66.7) | 2.46b | 0.19 |

| ≥ 5 equipment | 135 (64.6) | 2 (33.3) | ||

| Socioeconomic status category | ||||

| Very low | 41 (19.6) | 2 (33.3) | 1.89b | 0.53 |

| Low | 122 (58.4) | 4 (66.7) | ||

| Middle | 40 (19.1) | 0 (0) | ||

| High | 6 (2.9) | 0 (0) |

Table 4: Association between adult attitude regarding understanding and tolerance of mental illness and their socioeconomic characteristics.

Regarding integrating people with mental and it association with their socio-demographic characteristics, we found that females had significantly more positive attitudes than males (p=0.001) (Table 5). Moreover, participants with low crowding index had significantly more positive attitude regarding the causes of mental illness and the need for special services, compared to those with high crowding index (p=0.023) (Table 6).

| Variables | Attitude | Test-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n= 183) |

Negative (n= 32) |

|||

| Age (years), Mean ± SD | 42.12 ± 12.68 | 46.84 ± 12.59 | -1.95 | 0.053 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 59 (32.2) | 2 (6.3) | 9.05b | 0.001* |

| Female | 124 (67.8) | 30 (93.8) | ||

| Occupation, n (%) | ||||

| Housewife | 116 (63.4) | 29 (90.6) | 8.44c | 0.11 |

| Unskilled manual work | 20 (10.9) | 1 (3.1) | ||

| Skilled manual work | 10 (5.5) | 0 | ||

| Trades | 8 (4.4) | 1 (3.1) | ||

| Semiprofessional/clerk | 27 (14.8) | 1 (3.1) | ||

| Professional | 2 (1.1) | 0 | ||

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| Illiterate | 66 (36.1) | 18 (56.3) | 9.25c | 0.12 |

| Read and write | 36 (19.7) | 7 (21.9) | ||

| Primary school | 24 (13.1) | 5 (15.9) | ||

| Secondary | 28 (15.3) | 1 (3.1) | ||

| Intermediate | 17 (9.3) | 0 | ||

| Graduate | 9 (4.9) | 1 (3.1) | ||

| Postgraduate | 3 (1.6) | 0 | ||

| Economy, n (%) | ||||

| In debt | 47 (25.7) | 13 (40.6) | 5.51c | 0.13 |

| Just meet routine expenses | 95 (51.9) | 10 (31.3) | ||

| Meet routine expenses and emergencies | 28 (15.3) | 7 (21.9) | ||

| Able to save/invest | 13 (7.1) | 2 (6.3) | ||

| Health care, n (%) | ||||

| More than one source | 70 (38.3) | 12 (37.5) | 3.69c | 0.29 |

| Free governmental health services | 46 (25.1) | 11 (34.4) | ||

| Health insurance | 14 (7.7) | 4 (12.5) | ||

| Private health facilities | 53 (29) | 5 (15.6) | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | 156 (85.2) | 28 (87.5) | 0.34c | 0.92 |

| Urban slum | 22 (12) | 4 (12.5) | ||

| Urban | 5 (2.7) | 0 | ||

| Crowing index | ||||

| ≤ 1 person per room | 91 (49.7) | 14 (43.8) | 0.389b | 0.57 |

| > 1 person per room | 92 (50.3) | 18 (56.3) | ||

| Family Equipment | ||||

| < 5 equipment | 62 (33.9) | 16 (50) | 3.06b | 0.11 |

| ≥ 5 equipment | 121 (66.1) | 16 (50) | ||

| Socioeconomic status category | ||||

| Very low | 36 (19.7) | 7 (21.9) | 4.85c | 0.16 |

| Low | 103 (56.3) | 23 (71.9) | ||

| Middle | 38 (20.8) | 2 (6.3) | ||

| High | 6 (3.3) | 0 | ||

Table 5: Association between adult attitude regarding integrating people with mental illness and their socioeconomic characteristics.

| Variables | Attitude | Test-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n= 208) |

Negative (n= 7) |

|||

| Age (years), Mean ± SD | 42.81 ± 12.81 | 43.28 ± 11.93 | 0.034a | 0.92 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 59 (28.4) | 2 (28.6) | 0.001c | 0.91 |

| Female | 149 (71.6) | 5 (71.4) | ||

| Occupation, n (%) | ||||

| Housewife | 139 (66.8) | 6 (85.7) | 2.42c | 0.84 |

| Unskilled manual work | 20 (9.6) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| Skilled manual work | 10 (4.8) | 0 | ||

| Trades | 9 (4.3) | 0 | ||

| Semiprofessional/clerk | 28 (13.5) | 0 | ||

| Professional | 2 (1) | 0 | ||

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| Illiterate | 79 (38) | 5 (71.4) | 3.12c | 0.84 |

| Read and write | 42 (2.2) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| Primary school | 28 (13.5) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| Secondary | 29 (13.9) | 0 | ||

| Intermediate | 17 (8.2) | 0 | ||

| Graduate | 10 (8.2) | 0 | ||

| Postgraduate | 3 (1.4) | 0 | ||

| Economy, n (%) | ||||

| In debt | 56 (26.9) | 4 (57.1) | 2.68c | 0.35 |

| Just meet routine expenses | 102 (49) | 3 (42.9) | ||

| Meet routine expenses and emergencies | 35 (16.8) | 0 | ||

| Able to save/invest | 15 (7.2) | 0 | ||

| Health care, n (%) | ||||

| More than one source | 77 (37) | 5 (71.4) | 3.71c | 0.23 |

| Free governmental health services | 57 (27.4) | 0 | ||

| Health insurance | 18 (8.7) | 0 | ||

| Private health facilities | 56 (26.9) | 2 (28.6) | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | 177 (85.1) | 7 (100) | 0.74c | 0.66 |

| Urban slum | 26 (12.5) | 0 | ||

| Urban | 5 (2.4) | 0 | ||

| Crowing index | ||||

| ≤ 1 person per room | 105 (50.5) | 0 | 9.6c | 0.014* |

| > 1 person per room | 103 (49.5) | 7 (100) | ||

| Family Equipment | ||||

| < 5 equipment | 74 (35.6) | 4 (57.1) | 1.29c | 0.43 |

| ≥ 5 equipment | 134 (64.4) | 3 (42.9) | ||

| Socioeconomic status category | ||||

| Very low | 43 (20.7) | 0 | 3.77c | 0.27 |

| Low | 119 (57.2) | 7 (100) | ||

| Middle | 40 (19.2) | 0 | ||

| High | 6 (2.9) | 0 |

Table 6: Association between adult attitude regarding causes of mental illness and the need for special services and their socioeconomic characteristics.

The current study assessed the attitude of the adult population towards mental illnesses. In general, people adopted a negative attitude regarding their fear and exclusion of patients with mental illness. Siu et al. assessed the attitude of Chinese community towards mental illness and found that less than one-third felt afraid of talking to people with mental illness and opposed the presence of residential hostels for people with mental illness near to their households [9]. In a similar study in Ghana, the majority of the participants agreed that mentally-ill individuals should be hospitalized as soon as they show any signs. More than half of the participants thought that mentally-ill were a burden on the society; however, more than half of the participants also disagreed that it was foolish to marry a previously mentally-ill man or that people with mental illness should be excluded from taking public office [10]. On the other hand, in an Ethiopian study, the majority of participants agreed that a woman would be foolish to marry a someone who was mentally-ill and that they wouldn't live next door to someone with mental illness [11]. Interestingly, Rusch et al examined the link between endorsing genetic versus neurobiological causes and attitudes toward people with mental illness. They found that participants who regarded mental disorders as genetic in origin reported to fear mentally-ill individuals and to socially avoid them more than participants who adopted a neurobiological model of mental illness [12].

Participants showed a huge understanding and tolerance towards mental illness and mentally-ill people. Similarly, Barke et al reported that the Ghanaian community adopted a tolerant attitude towards mental illness. In particular, more than half of their participants felt that mentally-ill persons deserve sympathy and have for too long been the subject of ridicule, Moreover, the majority felt responsible to provide the best possible care for the mentally-ill [10]. Meanwhile, in the English community, people were even more tolerant. Over 90% felt responsible to provide the best possible care for mentallyill [13]. Contrary to these findings, the Ethiopian study reported that the majority of their participants rejected the statement “We need to adopt a far more tolerant attitude toward the mentally ill in our society” and agreed that mentally-ill didn't deserve sympathy and were better to be avoided [11]. These differences in attitude are probably due to socio-demographic variations of the studied populations.

Our participants supported integrating patients with mental illness into the community. They agreed that it's the best therapy for many mentally-ill people; however, they showed less support of trusting a previously mentally-ill woman as a babysitter and that mentally-ill should have equal job opportunities. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that people might want to help mentally-ill by providing them the best care, but due to public fear of mentally-ill, they wouldn't want to interact with someone mentally-ill or involve him/her into their daily life.

Evans-Lacko et al reported that about 78% of their participants viewed mental illness like any other illness and that mentally-ill should be a part of the community, but only 22.6% would trust a once mentally-ill women to be a babysitter [13]. Meanwhile, Barke et al found that 54.6% of their participants agreed that no one has the right to exclude the mentally-ill from their neighbourhood; yet, 42.1% believed that the mentally-ill should be isolated from the community [10]. In the current study, participants strongly believed that mentally-ill people can be easily distinguished from normal people. Barke et al found that 79.7% of their Ghanaian participants agreed with this, compared to 18.3% in the English population [10,13]. This may reflect the level of health care service provided. Barke et al suggested that the statement ‘‘there is something about mentally ill people that makes them easy to tell from normal people’’ does not necessarily reflect participants' stigmatizing attitudes, but reflects a context where psychiatric treatment is the exception rather than the rule [10].

Our participants thought that the lack of self-discipline and willpower were of the main causes of mental illness. Barke et al reported that 61.2 % of their Ghanaian participants saw the lack of moral strength and willpower as a cause of mental illness [10]. However, in the English study, Evans-Lacko et al reported that only 15.7 % of their participants agreed with this item [13]. The socio-demographic differences between the studied populations can explain the variation in results. Moreover, other studies reported public beliefs of other causes of mental illness. A study by Bener and Gholoum reported that the majority of the studied Arabs thought that alcohol or drug abuse may result in mental illness [14]. In Egypt, people thought mental illnesses were due to exposure to sudden fright, possession of evil spirits, use of magic, head accidents, emotional trauma, heredity, or due to the evil eye [15]. Meanwhile, there was less agreement of the statement “there are sufficient existing services for people with mental illness”. The English study reported that only 24% of their participants agreed with this statement [13], where as in the Ethiopian study, 65% agreed with the statements [11]. This may reflect people expectations and perceptions of sufficient services more than the true existing service. A study conducted in Egypt clarified that families of mentally-ill individuals reported lack of support and negative attitudes from health professionals. Moreover, they indicated that the majority of Egyptians prefer visiting private practitioners, if they can afford to, rather than being admitted to hospitals because of the stigma associated with psychiatric treatment [15].

In general, we found no significant association between age, gender and public attitude to mental illness, except for their beliefs of mental illness causes which were significantly related to age. Participants over 35 years strongly agreed that mental illness was due to lack of self-discipline and willpower, compared to younger individuals (<35 years). Pang et al clarified that youths were probably more exposed to information regarding mental illness through the internet and social media [16]. Meanwhile, other studies reported a significant association between age, gender and people attitude to mental illness. Holzinger et al demonstrated that women had more positive reactions and were less angry with mentally-ill people than men; however, women also reported more feeling more fear toward these people [17] Angermeyer et al reported that negative attitudes towards mental illness were positively associated with age [18]. Meanwhile, another study reported that those above 60 years of age agreed the most to allow their kids to befriend with psychiatric patients [19]. The attitude toward mental illness didn't differ significantly between people who don't know any person with mental disorders, those who know at least one person with mental disorders, and those who recognized themselves as being mentallyill. Similarly, Crisp et al found no significant difference in attitude between people who know someone mentally-ill and others [20]. Yet, another study reported an inverse correlation between familiarity and social distance, where individuals who were more familiar with mental illness were less socially distant [21]. Brynjolfsson clarified that less familiarity with mental illness predicted more prejudice attitudes [22]. The inconsistency of the results is probably due to the smaller sample size in the current study, where we only included 38 participants, while Brynjolfsson conducted a study on 218 participants and Corrigan et al included 151 participants.

This study was a cross-sectional regional study therefore; the findings of the current study cannot be generalized, and may not reflect the beliefs and attitudes of the Egyptian community.

This study revealed an inconsistent attitude of adult population. Although they adopted a negative attitude regarding their fear and exclusion of patients with mental illness, they showed a huge understanding and tolerance towards mental illness and mentallyill people and supported integrating patients with mental illness into the community. Anti-stigma programs are needed to boost people acceptance of mental illness and strategies to increase social contact of the public with mentally-ill individuals should be considered when designing these programs. Moreover, multicentric large studies are needed to have a clearer view of the Egyptian community attitude to mental illness.

Citation: Atta MS, Abdo HA, Nour-Eldein H, Tosson EE (2020) Assessmentof Adult Attitude towards Mental Illness among Attendees of Family Medicine Outpatient Clinic at Suez Canal University Hospital, Ismailia Governorate. Fam Med Med Sci Res 9: 253. doi:10.35248/2327-4972.20.9.253.

Received: 22-Jan-2020 Accepted: 07-Aug-2020 Published: 14-Aug-2020 , DOI: 10.35248/2327-4972.20.9.253

Copyright: © 2020 Atta MS, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited