Poultry, Fisheries & Wildlife Sciences

Open Access

ISSN: 2375-446X

ISSN: 2375-446X

Research Article - (2017) Volume 5, Issue 2

This study was carried out to evaluate the beekeeping husbandry practices and honey production in three districts of Waghimra Zone (Abergell, Sekota and Gazgibala). To collect the data, 332 respondents were selected using systematic random sampling from the three districts. Data were collected using semi-structured questionnaire, observation, key information interview and focus group discussion. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics and ANOVA using SPSS version-20. The overall trends of bee colony and honey production are declining over the last 5 years. The average honey yield per year/colony was 10.16, 13.61 and 23.32 kg for traditional, transitional and moveable frame hives, respectively. Most of the respondents (68.4%) in the study area practiced traditional beekeeping whereas 7.8 and 23.8% of the respondents practiced transitional and modern bee keeping system, respectively. There was a significant difference (p<0.05%) among the three agro-ecologies on traditional honeybee colonies holding per household. The major source of household income is from crop production 27.7%, livestock production 23.8%, beekeeping activities 16.9% and irrigation 15.4%. Therefore, beekeeping is the third ranking source of income for the households in the study area. Most of the respondents (bee keepers) visit their bees some times and rarely in months. Generally, beekeeping is still the 3rd major source of income for the households in the study area next to crop and livestock production, however, the expected output or income has not earned from this subsector due to various challenges existed in the study area. Thus, based on these findings, improving the awareness of the beekeepers through training is important to address the identified challenges and to improve the overall honey production in Waghimara Zone.

<Keywords: Bee colony; Beehives; Beekeeping practice; Honey production

Ethiopia is known for its tremendous variation of agro climatic conditions and biodiversity which favoured the existence of diversified honeybee flora and huge number of honeybee colonies [1]. It has the largest bee population in Africa with over 10 million bee colonies, out of which about 5 to 7.5 million are estimated to be hived while the remaining exist in the wild [2]. The country has a longstanding beekeeping practices that has been an integral part of other agricultural activities, where more than one million households keep honeybees [1,3]. Beekeeping subsector is dominantly for small-scale farmers and is contributing significantly to the increment off-farm income and toward poverty reduction in rural areas [2]. Honey is considered as a cash crop and only about 10% of the honey produced in the country is consumed by the beekeeping households [4]. The remaining 90% is sold for income generation [5].

Even though, Ethiopia has immense natural resources for beekeeping activity, this sub sector has been devastated by various complicated constraints as clearly stated by Geberetsadik and Negash [6]. According to Kinati et al. [7], drought, decline in vegetation coverage and subsequent changes in natural environments, pests and predators, indiscriminate applications of chemicals are causes for low honey productivity and improved beekeeping practices. In line with these impeding factors, there are also other major constraints that affect beekeeping subsector in Ethiopia such as: lack of beekeeping knowledge, shortage of skilled manpower, shortage of bee equipment’s, poor infrastructural development, and shortage of bee forage and lack of research extension [8].

To put in place appropriate remedial interventions that would lead to enhanced productivity of the beekeeping subsector, understanding the prevailing overall beekeeping husbandry practices and understanding the major constraints of honey production is very vital. This necessitates the need for generating site specific database under specific production scenarios. In this regard, little research has been done so far to identity the overall smallholder beekeeping husbandry practices and its major production constraints in Waghimara Zone. In this research, it is endeavoured to fill this existing information gap. Hence, the objective of this study was to investigate the smallholder beekeeping husbandry practice, production constraints and to suggest possible solutions for the identified constraints at their production environment.

This study was conducted in three sites namely Abergell, Sekota and Gazgibala districts in Waghimara Zone of Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. The three districts were selected among the many districts due to their potential for honey production.

The area is located at 12° N latitude and 38° E longitudes at an altitude of 500-3500 masl with annual rain fall of 150-700 mm which is an erratic type of rainfall. The annual average temperature ranges from 15°C to 40°C.

Cattle, small ruminant, poultry and equines are the major livestock species kept in the zone. In the Waghimara Zone there is huge potential of beekeeping, which is an integral part of the animal husbandry. It is a common culture and farming practice. Most of beehives are virtually kept at backyards and modern beehives are common that farmers’ have familiarized with its use nowadays (Table 1).

| No | Districts | Area Coverage | Bee Resource | Bee Colony Per Km2 (h/r) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km2 (h/r) | Zonal Share | Bee Colony | Zonal Share | |||

| 1 | Sekota town | 9375.96 | 1.07 | 1,544 | 2.02 | 0.165 |

| 2 | Sekota | 167156.3 | 19.03 | 21,702 | 28.37 | 0.13 |

| 3 | Dehana | 167631.4 | 19.09 | 12,105 | 15.82 | 0.072 |

| 4 | Ziquala | 170162.6 | 19.38 | 14,771 | 19.31 | 0.868 |

| 5 | Abergelle | 160658.6 | 18.29 | 3,393 | 4.44 | 0.021 |

| 6 | Sehala | 95077.15 | 10.83 | 8,106 | 10.6 | 0.085 |

| 7 | Gazgibala | 108133.2 | 12.31 | 14,874 | 19.44 | 0.138 |

| Subtotal Zonal | 878195.3 | 76,495 | 1.479 | |||

Source from: Waghimra Zone Animal and Fish Resources Department, 2016.

Table 1: Waghimra Zone bee colony distribution by districts.

Study design

Cross sectional study design was used for this assessment since the study was conducted in the three districts having different agroecologies (Highland, Midland and Lowland). Thus, the data were collected from three districts with different agro-ecology through data gathering instruments such as: household survey with semi-structured questionnaire, observation, key informant interview and focus group discussion. The design helped us to assess and make comparative analysis of the data collected from the three districts and nine peasant associations.

Sampling techniques and sample size

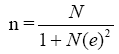

Purposive and systematic random sampling techniques were used for this study. From the total of 7 districts in Waghimra Zone, three of them were selected purposely based on their agro-ecology and beekeeping potentials. Totally nine PAs were selected out of 67 PAs from the targeted districts by considering their agro-ecology. The sample households (beekeepers) were selected using Systematic (Nth) sampling technique that gives equal chance for the Nth representative samples from a list of farmers participated in beekeeping activity within the nine PAs. Thus, a single household respondent was used as sampling unit and the total households included in this study were determined according to the formula given by Yamane (1967) with 95% confidence level of the households from the total beekeepers (1961) in the 9 PAs were selected as follow as:

Were n=Sample size; N=population size; e=the desired level of precision.

Totally, 332 sample households (beekeepers) were determined from the three target districts and hence, the representative samples from each district (Sekota=165, Gazgibala=105 and Abergelle=62) were also determined based on the number of beekeeper households in each district. In addition, sample size (N) was also tested by the formula recommended by Andrew et al. [9] as N=0.25/SE2, where N is sample size, and SE is the standard error in order to validate its significance level. Based on this, the SE was 3%, which is less than 5% that confirmed, as it was more significant and appropriate to represent the target total population.

Methods and data collection

In order to carry out this field survey study, discussion was undertaken initially with Waghimra Zone head of Livestock and Fisheries Resources Department and bee experts of the selected districts. In addition, the researcher made a discussion with the heads of targeted districts Livestock and Fish Resources Head Office and bee experts for the selection of nine PAs. In the study, primary and secondary data were used to generate qualitative and quantitative information. In addition, the secondary data that has relevance to this study was collected from both published and unpublished sources.

Questionnaire: The primary data were collected from 332 household beekeepers using semi-structured questionnaire on: demographic and socio-economic data, numbers of bee colonies, honey production potential, current practices, and other beekeeping practices were gathered from household beekeepers.

Focus group discussion: FGD was undertaken with PAs leaders; development agents (Das) and beekeeper farmers with best experience (30 participants, i.e., 10 participants in one district) were purposely selected and participated in three districts. The FGD was carried out with providing guidelines (checklists) for participants and the discussion focused on: the extent of current beekeeping practice, the techniques they used, trends of beekeeping practice, potential areas in beekeeping activities and honey production systems in targeted districts.

Key informant interview: Key informant interview was under taken with three Zone bee and livestock experts, nine bee and livestock experts in 3 districts, 9 model beekeeper farmers and 3 beekeeping researchers. Totally 24 key informants were interviewed in order to gather more of qualitative information deeply that was used to supplement, crosscheck and validate the data obtained through household survey.

Observation: Observation was anther instrument used in this study. From the total 4,250 beehives (traditional, modern and transitional), 366 sample hives were selected for field observation from 50 randomly selected households with in the 332 beekeeper sample household respondents. During observation, the researcher used guidelines on different beekeeping activities such as: framed and traditional hive placement, hives management, pest and predator, hive products, honeybee flora condition, dry season feeding and seasonal bee colony activities.

Method of data analysis

The quantitative data were organized and entered in to Microsoft Office Excel 2007 and analysed using descriptive statistics and one way ANOVA using IBM SPSS statistics version-20.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents

As presented in Table 2 from the total sample (332), 93.4% were male and 6.6% female headed beekeeper, respectively. This result agrees with Sebeho [10] who reported that 93% of the interviewed beekeepers were male and only 7% were female headed beekeeper. Similarly, Beyene and Verschuur [11] reported that 94.4% of the interviewed small scale beekeepers involved in honey value chain were males, where as 5.6% involved in honey value chain were females. Thus, it is possible to generalize that only few number of women participated in the beekeeping practice in the study area because there were different socio-cultural factors that impeded females to engage in beekeeping practice such as: beekeeping activities are mostly done at night; females cannot afford the current bee colonies and beekeeping equipment price; females could not resist the aggressive behaviour of bees. Almost half of 49.7% beekeeping participants lived in the high land agroecology whereas, the lowest number of beekeeping participants 18.7% lived in the low land areas and the rest 36.6% of them lived in mid land agro-ecology.

| Category | Variables | Study area | Over all (N=332) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL (N=165) | ML (N=105) | LL (N=62) | F | % | |||||

| F | % | F | % | F | % | ||||

| Sex | Male | 157 | 95.2 | 99 | 94.3 | 54 | 87.1 | 310 | 93.4 |

| Female | 8 | 4.8 | 6 | 5.7 | 8 | 12.9 | 22 | 6.6 | |

| Total | 165 | 100 | 105 | 100 | 62 | 100 | 332 | 100 | |

| Age (years) | 15-29 years | 33 | 20 | 19 | 18.1 | 2 | 3.2 | 54 | 16.3 |

| 30-49 years | 75 | 45.5 | 48 | 45.7 | 22 | 35.5 | 145 | 43.7 | |

| 50-64 years | 34 | 20.6 | 32 | 30.5 | 33 | 53.2 | 99 | 29.8 | |

| >65 years | 23 | 13.9 | 6 | 5.7 | 5 | 8.1 | 34 | 10.2 | |

| Marital status | Single | 5 | 3 | 6 | 5.7 | 3 | 4.8 | 14 | 4.2 |

| Married | 128 | 77.6 | 80 | 76.2 | 44 | 71 | 252 | 75.9 | |

| Widowed | 15 | 9.1 | 11 | 10.5 | 10 | 16.1 | 36 | 10.8 | |

| Divorced | 17 | 10.3 | 8 | 7.6 | 5 | 8.1 | 30 | 9 | |

| Educational status | Illiterate | 91 | 55.2 | 53 | 50.5 | 27 | 43.5 | 171 | 51.5 |

| Reading and writing | 30 | 18.2 | 18 | 17.1 | 11 | 17.7 | 59 | 17.8 | |

| Primary (1-4) | 30 | 18.2 | 20 | 19 | 14 | 22.6 | 64 | 19.3 | |

| Junior (5-8) | 10 | 6.1 | 10 | 9.5 | 6 | 9.7 | 26 | 7.8 | |

| Secondary (9-12) | 4 | 2.4 | 4 | 3.8 | 4 | 6.5 | 12 | 3.6 | |

| Experience in beekeeping activity (years) | 1-5 years | 38 | 23 | 24 | 22.9 | 15 | 24.2 | 77 | 23.2 |

| 6-10 years | 43 | 26.1 | 27 | 25.7 | 16 | 25.8 | 86 | 25.9 | |

| 11-20 years | 40 | 24.2 | 25 | 23.8 | 15 | 24.2 | 80 | 24.1 | |

| >21years | 44 | 26.7 | 29 | 27.6 | 16 | 25.8 | 89 | 26.8 | |

| Family size | 1-5 family | 52 | 31.5 | 33 | 31.4 | 20 | 32.3 | 105 | 31.6 |

| 6-10 family | 108 | 65.5 | 67 | 63.8 | 42 | 67.7 | 217 | 65.4 | |

| 11-15 family | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2.9 | 2 | 3.2 | 10 | 3 | |

| Position of household head in community | Political leader | 67 | 40.6 | 43 | 40.9 | 25 | 40.3 | 135 | 40.7 |

| Spiritual leader | 15 | 9.1 | 10 | 9.5 | 6 | 9.7 | 31 | 9.3 | |

| Elder | 17 | 10.3 | 11 | 3.3 | 6 | 9.7 | 34 | 10.2 | |

| Community member | 39 | 23.6 | 25 | 23.8 | 15 | 24.2 | 79 | 23.8 | |

| Kebele team leader | 12 | 7.3 | 7 | 6.7 | 4 | 6.5 | 23 | 6.9 | |

| Kebele police | 15 | 9.1 | 9 | 8.6 | 6 | 9.7 | 30 | 9 | |

Source: Field survey, December-March, 2016/17; HL: Highland; ML: Midland; LL: Lowland; N: Number of respondents; F: Frequency.

Table 2: Demographic characteristics of the sample household beekeepers.

The majority of beekeepers 59.9% age in the study area ranges between 15-49 years. This indicates more than half of the beekeepers in study area were under the productive age who can actively engage in beekeeping practice. This result was supported by the finding of Kinati et al. [7] who reported that average age of beekeeper in Gomma districts South West Ethiopia was 40.47 years.

As indicated in Table 2 from the total respondents, about 51.5% of them were illiterate, 19.3% attended primary education, 17.8% of them can read and write; 7.8% beekeepers attended junior education and the rest only 3.6% of beekeepers attended secondary education. This result was similar with the findings of Beyene and Verschuur [11] that they reported 33.3% of beekeeper respondents were illiterate. On the contrary, it varies from the findings of Belie [12] who reported that only 15.1% were illiterate whereas 84.9% of them were literate. The difference might be due to in accessibility of both formal and informal education in the Waghimara Zone especially in previous years.

Regarding respondents experience in beekeeping activity, 26.8% beekeepers have more than 21 years’ experience, 25.9% have from 6 to 10 years, 24.1% have between 11-20 years and the rest 23.2% of them had an experience of beekeeping from 1-5 years. Kinati et al. [7] reported as beekeper had an average experience of beekeeping 5.66 years. Therefore, beekeepers in this study area had better experience of beekeeping than Kinati’s report.

As indicated in Table 2, 65.4% of respondents had the family size of (6-10); (30.6%) them had family size of (1-5) and the rest (3%) of beekeepers had (11-15) family size. This indicated that the average family size of Waghimara Zone is so large that need diversified source of income in addition to crop production and animal husbandry for generating income like beekeeping activities in order to improve farmers economic status. The current study was supported by Geberetsadik and Negash [6] which revealed that the minimum and maximum family size of respondents were 5 and 7, respectively.

Socio-economic characteristic of the respondents

The major source of respondents households income were from crop production which accounted 27.7%, livestock production 23.8%, beekeeping activities 16.9% and irrigation which accounted 15.4% in descending order as shown in Table 3.

| Category | Variables | Study area | Over all (N= 332) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL (N=165) | ML (N=105) | LL (N=62) | Freq | % | |||||

| Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | ||||

| Source of income | Crop prod | 52 | 31.5 | 23 | 21.9 | 17 | 27.4 | 92 | 27.7 |

| Livestock prod | 43 | 26.1 | 21 | 20 | 15 | 24.2 | 79 | 23.8 | |

| Beekeeping | 36 | 21.8 | 10 | 9.5 | 10 | 16.1 | 56 | 16.9 | |

| Irrigation | 23 | 13.9 | 22 | 21 | 6 | 9.7 | 51 | 15.4 | |

| Trade | 7 | 4.2 | 15 | 14.3 | 5 | 8.1 | 27 | 8.1 | |

| Service | 4 | 2.4 | 14 | 13.3 | 4 | 6.5 | 22 | 6.6 | |

| Fish prod | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8.1 | 5 | 1.5 | |

| Major crop cultivation in the study area | Barley | 42 | 25.5 | 23 | 21.9 | 2 | 3.2 | 67 | 20.2 |

| Sorghum | 28 | 17 | 22 | 21 | 20 | 32.3 | 70 | 21.1 | |

| Teff | 22 | 13.3 | 21 | 20 | 16 | 25.8 | 59 | 17.8 | |

| Pea | 17 | 10.3 | 10 | 9.5 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 8.1 | |

| Wheat | 41 | 24.8 | 15 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 56 | 16.9 | |

| Bean | 15 | 9.1 | 14 | 13.3 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 8.7 | |

| Oil crop | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 24.2 | 15 | 4.5 | |

| Cowpea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 14.5 | 9 | 2.7 | |

Source: Field survey, December-March, 2016/17; HL: Highland; ML: Midland; LL: Lowland; N: Number of respondents; F: Frequency.

Table 3: Socio-economic characteristics of the sample household in beekeeping.

Therefore, beekeeping is the third ranking source of income for the households in the study area.

In relation to agro-ecology, beekeeping accounted 21.8% source of income for households next to crop and livestock production which accounted 30.5% and 26.1%, respectively in high land area of the study area and similarly beekeeping is third ranking source of income in low land area which accounted 16.1% next to crop and livestock production that accounted 27.4% and 24.2%, respectively. On the other hand in the mid land area, beekeeping accounted only 9.5% as source of income which is the lowest compare to high land and low land agro-ecologies as indicated in Table 3. In line with this result, Beyene and Verschuur [11] reported that beekeeping ranks second source of income accounted as 26.27% share of income.

Livestock and honeybee colonies holding of sample households

The major types of livestock owned by respondents on average were goats 22.34, sheep 21.12, bee colony 13.11, poultry 9.46, cattle 6.03 and equines 1.76 per household in descending order as stated in Table 4. Regarding the number of bee colonies per household, the minimum and the maximum bee colonies were 2 and 84, respectively with an average of 14.64 bee colonies. There is significant difference among beekeepers in having bee colonies. In supporting this finding, Gebru [13] confirmed that beekeeper owned a maximum of 100 bee colonies and a minimum of 1 bee colony and with an average bee colonies of 5.8 per household. Beekeepers revealed as they practiced beekeeping for getting cash income, consumption, dowry or gift and for breeding in descending order. This was similar with the findings of Yemane and Taye [14] who reported that the main purpose of beekeeping was for both income and household consumption depending on their importance.

| Variables | N | Min | Max | Mean | S.E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cattle per household head | 332 | 2 | 15 | 6.03 | 0.188 |

| Number of goat per household head | 332 | 5 | 100 | 22.34 | 0.974 |

| Number of sheep per household head | 332 | 3 | 84 | 21.12 | 1.182 |

| Number of pultry per household head | 332 | 4 | 30 | 9.46 | 0.226 |

| Number of bee colonies per household head | 332 | 2 | 84 | 14.64 | 0.937 |

| Number of equines per household head | 332 | 1 | 5 | 1.76 | 0.058 |

Source: Field survey, December-March, 2016/17; SE: Standard Error; N: Number of respondents.

Table 4: Average livestock and honeybees number per household head.

Source of bee colonies to start beekeeping activities

As presented in Table 5, 38.3% of respondents revealed that they started beekeeping by catching swarms. This means there is a potential in the area for starting beekeeping activities simply by catching swarms instead of purchasing. However, if the swarming is from farmer’s bee colonies this condition is a disadvantage. Most of the time swarming is takes place from August to September and March up to June. In line with this finding, as 38.7% households started beekeeping practice with catching swarms whereas 36% of them started it with both catching swarms and purchasing from the market in Hadya Zone. Moreover, 49.2% of beekeeper started by catching swarms.

| Category | Variables | % of the Respondents (N= 332) N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Placement of bee colonies in the study area | Back yard | 156 (47.0) |

| Under the eaves of the house | 51 (15.4) | |

| Inside the house with family | 67 (20.2) | |

| In area closure | 26 (7.8) | |

| Hanging near home stead | 22 (6.6) | |

| Hanging in the forest | 10 (3.0) | |

| Total | 332 (100%) | |

| Source of bee colonies to start beekeeping activities in the study area | Catching swarms | 127 (38.3) |

| Gift from parents | 58 (17.5) | |

| Buying | 48 (14.5) | |

| Training | 7 (2.1) | |

| Self interest | 37 (11.1) | |

| Agri office | 28 (8.4) | |

| NGO | 27 (8.1) | |

| Total | 332 (100%) | |

| Reason to engage in beekeeping activities | Income generating | 112 (33.7) |

| Easy to perform to gather with other activity | 60 (18.1) | |

| House expense | 53 (16.0) | |

| Inherited from parents | 53 (16.0) | |

| Training | 9 (2.7) | |

| As indication of wealth | 45 (13.6) | |

| Total | 332 (100%) |

NB: Placement of Transitional beehives and Modern beehive are 58.4% back yard and 41.6% in area closure, N: Number of sampled respondents.

Table 5: Placement, source and engage of bee colonies in the study area.

Placement of beehive colonies

As shown in Table 5, 47% beekeepers in the study area kept their traditional bee hives around their homestead (backyard); 20.2% put inside the house; 15.4% put under the eaves of the house; 7.8% put in the area closure; 6.6% hanging near homestead whereas 3% hanging their beehives in the forest. On the other hand, beekeepers of transitional and modern hives kept 58.4% in backyard and 41.6% in area closure. This result is in agreement with Belie [12] who reported that 47.1% of beekeepers kept their traditional hives in the backyard mainly to enable close supervision of colonies.

It is also similar with the findings of Yirga and Mekonen [15] who reported as the majority of beekeepers were keeping their bees in backyard and inside the house, which accounts 46.2% and 48.5%, respectively.

Reasons of beekeepers to keep honey bees

As indicated in Table 5, sampled beekeepers reported as they engaged in beekeeping activities for different reasons. 33.7% them reported as they engaged in beekeeping practice to generate income; 18.1% due to its easy nature to perform with other activities; 16% to cover house expense and inheriting from parent, respectively whereas 13.6% of beekeepers gave their reason of being engaged in beekeeping because it is an indication of wealth and the rest small number of beekeepers 2.7% engaged in this practice due to training. This is in line with the reports of CSA [16] from the total honey production in Ethiopia; about 54.68% was used for sale, 41.22% for household consumption, 0.34% used as payment for wage in kind and the rest 3.75% used it for other purposes. The findings of Yemane and Taye [14] ranked the purpose of keeping honeybees in descending order as follows: 75% of respondents practiced it both for income and household consumption; 16% for the purpose of only income generation and the rest 9% of them only for home consumption.

Experience of beekeeper on apiary site selection

Regarding apiary site selection, 23.8% of beekeepers reported as they selected apiary site by their own via adapting experience from their ancestors; 15.4% of beekeepers selected apiary site by considering site to be free from bees enemies and predators; 13.9% selected apiary site by considering site to be free from any disturbance; 8.1% prefer site with the feasibility of flora; 7.8% selected site prevailed area; 6.9% apiary site which is potential to beekeeping whereas 6.9% didn’t give any attention on apiary site selection; 6.3% selected apiary site by considering the availability of water and other 6.3% of them consider close supervision and the rest 4.5% of beekeepers selected apiary site with orientation to sunlight as indicated in Table 6. These result is in line with Belie [12] findings which states that the main criteria for apiary site selection of the sample household beekeepers were: close supervision, owned from ancestor’s, availability of flora, orientation to sunlight, availability of water, free from bee enemies and predators, free from any animals and human disturbances, combination of criteria, wind direction, and some beekeepers have no apiary site selection criteria at all.

| Category | Variables | Frequency of the respondents (N=332) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | ||

| Types of technology | Traditional hives | 227 | 68.4 |

| Transitional hives | 26 | 7.8 | |

| Modern hives | 79 | 23.8 | |

| Apiary site selected methods | Close supervision | 21 | 6.3 |

| Owned from ancestors | 79 | 23.8 | |

| Availability of flora | 27 | 8.1 | |

| Orientation to sun light | 15 | 4.5 | |

| Availability of water | 21 | 6.3 | |

| Free from bee enemies and predators | 51 | 15.4 | |

| Potentiality to beekeeping | 23 | 6.9 | |

| Free from any disturbance | 46 | 13.9 | |

| Area prevailing | 26 | 7.8 | |

| No selection | 23 | 6.9 | |

| Source of beehives | |||

| Traditional beehives | Constructed by him/her self | 189 | 83.4 |

| Constructed locally and bought | 38 | 16.6 | |

| Transitional beehives | Constructed by him/her self | 2 | 7.7 |

| Constructed locally and bought | 6 | 23.1 | |

| Supplied by Go on credit | 4 | 15.4 | |

| Supplied by GOs on free | 3 | 11.5 | |

| Supplied by NGO on credit | 5 | 19.2 | |

| Supplied by NGO on free | 6 | 23.1 | |

| Modern beehives | Bought from market | 8 | 10.1 |

| Supplied by GOs on credit | 28 | 35.4 | |

| Supplied by GOs on free | 5 | 6.3 | |

| Supplied by NGO on credit | 19 | 24.1 | |

| Supplied by NGO on free | 19 | 24.1 | |

Source: Field survey, December-March, 2016/17, N=number of respondents.

Table 6: Types of technologies, apiary site and source of beehives in the study area.

Types of technologies used in bee keeping activities

As illustrated in Table 6, most of 68.4% beekeepers reported as they used traditional beehives whereas 23.8% of them used modern beehives and the rest 7.8% used transitional hives for their beekeeping practice. Therefore, the majority of beekeepers in Waghimara Zone did not use improved technologies rather they practiced traditional way of beekeeping activity and hence, beekeepers have not been benefited as expected from this subsector. However, other management practices, pests, and predators, chemical spray also contributed for low productivity of honeybee in the study area.

In line to this study Beyene and Verschuur [11] reported that traditional beekeeping practice contributed to low yield and quality of bee products in Wonchi district South West Shewa Zone of Oromia. Moreover, low productivity and quality of bee products are the major economic impediments for beekeepers as Geberetsadik and Negash [6] justified in their study conducted in districts of Gedeo Zone, SNPRS.

Traditional beehives

As indicated in Table 6, 68.4% of beekeepers were used traditional hives for honey and bees wax production. This is due to lack of appropriate honey processing materials, lack of bee equipment’s and protective materials (like modern beehives, casting mold, frame wires, beeswax etc.) and skilled manpower. This result was in agreement with the findings of Yemane and Mekonen [14] as 87.80% of beekeeping practice covered by traditional beehives and the rest covered by 5.80%, 5.10% and 1.30% with traditional and transitional, traditional and modern beehives and all three types of beehives respectively. These indicated beekeepers highly depend on traditional beehives than modern and transitional beehives. Most of beekeepers 83.4% of them constructed their own traditional beehives from local materials such as: comb hives from lumber and others from mud (which is a mixture of clay, cow dung and ash), different trees, like Ekima (Terminalia glaucescens) and bamboo (Arundinaria alpine). However, the rest 16.6% beekeepers bought locally constructed beehives and some of them borrowed it from other beekeepers that had extra beehives.

As shown in Table 7, the average numbers of traditional hives owned per household were 8.79 ± 0.625 whereas the minimum and maximum hives per household were 2 and 84, respectively. The result indicated that there is no significant difference (P>0.05) among beekeepers in Waghimara Zone. According to Getu and Birhan [17] in and around Gonder, average numbers of traditional honeybee colony owned per household were 7.58 whereas the minimum and maximum beehives per household were 1 and 60. In relation to agro-ecology in the high land area, the average number of traditional hives per household was 9.3 ± 1.1, in the midland 7.2 ± 0.5 and in the lowland 10.13 ± 1.4. Beekeepers have more traditional beehives per household in low land area than other agro-ecologies. Specially, in the mid land area, beekeepers owning traditional beehives was less than high land and low land area.

| Type of Beehives | Min | Max | Study area | P –value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL | ML | LL | Over all | ||||

| N=165 | N=105 | N=62 | N=332 | ||||

| Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | ||||

| Taditional | 2 | 84 | 9.31 ± 1.105 | 7.18 ± 0.48 | 10.13 ± 1.36 | 8.79 ± 0.625 | 0.193NS |

| Transitional | 1 | 8 | 2.29 ± 0.302 | 2.04 ± 0.285 | 1.83 ± 0.306 | 2.11 ± 0.182 | 0.591NS |

| Modern | 1 | 21 | 3.78 ± 0.637 | 3.78 ± 0.44 | 7.38 ± 1.09 | 4.38 ± 0.414 | 0.001** |

**Significance at p<0.01%; NS: Non-significant at p>0.05; N: Number of respondents; SE: Standard Error; HL: Highland; ML: Midland; LL: Lowland.

Table 7: Number of beehive in the study area.

As shown in Table 8, in the highland area, the maximum and the minimum traditional beehives per household were 50 and 2, respectively with average number 13.59 ± 2.4 hives per household. In mid land area there was high variation of beekeepers in having traditional beehives per households with the minimum and maximum of 2 and 84, respectively, which was more than other two agro-ecologies and the average traditional hive per household was 26.6 ± 5.3. The average traditional hives per household in low land area was 16.4 ± 4.9 with SD (21.2) which is more than the high land area and less than the mid land area whereas the minimum and maximum beehives per household were 2 and 63, respectively. There were a significant difference (p<0.05%) on the practice of traditional beekeeping among the three agro-ecologies. In addition, traditional hives variability of having different shapes was attributed to the different climate conditions of the area and the beekeepers different honey production systems and techniques.

| Variables | Study area | N | Min | Max. | M ± SE | S.D | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional hives colony only owned/households | HL | 46 | 2 | 50 | 13.59 ± 2.37 | 16.11 | 0.037* |

| ML | 29 | 2 | 84 | 26.62 ± 5.33 | 28.708 | ||

| LL | 19 | 2 | 63 | 16.36 ± 4.99 | 21.211 | ||

| Transitional hive colony only owned/HH | HL | 16 | 1 | 8 | 3.38 ± 0.657 | 2.63 | 0.172NS |

| ML | 10 | 1 | 5 | 2.00 ± 0.471 | 1.491 | ||

| LL | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1.86 ± 0.553 | 1.464 | ||

| Framed hive colony only owned/HH | HL | 24 | 1 | 15 | 3.71 ± 0.724 | 3.544 | 0.03* |

| ML | 15 | 2 | 15 | 5.87 ± 1.032 | 3.998 | ||

| LL | 10 | 1 | 21 | 8.00 ± 2.006 | 6.342 | ||

| Traditional and Transitional hive colony owned/households | HL | 13 | 3 | 6 | 3.69 ± 0.328 | 1.182 | 0.822 NS |

| ML | 9 | 3 | 6 | 4.00 ± 0.441 | 1.323 | ||

| LL | 5 | 3 | 6 | 4.00 ± 0.632 | 1.414 | ||

| Traditional and Modern hive colony owned/households | HL | 38 | 3 | 30 | 10.95 ± 1.20 | 7.429 | 0.415NS |

| ML | 24 | 3 | 21 | 9.21 ± 1.169 | 5.725 | ||

| LL | 7 | 3 | 26 | 12.86 ± 3.08 | 8.174 | ||

| Transitional and Modern hive colony owned per households | HL | 19 | 2 | 5 | 3.42 ± 0.299 | 1.305 | 0.660 NS |

| ML | 12 | 2 | 5 | 3.00 ± 0.348 | 1.206 | ||

| LL | 10 | 2 | 5 | 3.20 ± 0.389 | 1.229 | ||

| Traditional, Transitional and Modern hive colony owned/HH | HL | 9 | 4 | 10 | 5.78 ± 0.722 | 2.167 | 0.886 NS |

| ML | 5 | 4 | 8 | 6.00 ± 0.707 | 1.581 | ||

| LL | 5 | 4 | 10 | 6.40 ± 1.030 | 2.302 |

*Significance at p<0.05%; NS: Non-significant at p>0.05; HL: highland; ML: midland; LL: lowland; N: Number of respondents; SD: Standard deviation; SE: Standard Error.

Table 8: Honeybee colonies holding per household in the study area.

Transitional beehives

Beekeepers who owned transitional beehives were 7.8% which was the smallest number as compared to traditional and modern beehives. As indicated in Table 7, the average numbers of transitional beehives owned per household was 2.11 ± 0.18 whereas the minimum and maximum hives per household was 1 and 8, respectively. There were none significant difference on the practice of transitional beekeeping among the three agro-ecologies.

Modern beehives

Among the beekeeper respondents, 23.8% of them replied as they had modern beehives for their beekeeping activity. This share was more than transitional hives and less than traditional beehives. Similarly, Kebede and Tadesse [18] reported 8.5% of household beekeepers owned traditional and modern beehives in Hadya Zone. This indicates that the adoption rate of improved technology (modern beehives) is very low because of the cost of constructing and purchasing of modern beehives and due to lack of harvesting and processing equipment’s to use modern and improved beehives. In modern (frame hive), the average number of hives per household was 4.38. This was better than the findings of Belie [12] with the average number of modern hives per household (3.73). In low land area, beekeepers had relatively more number of modern beehives per household (7.38) than other two agroecologies due to beekeepers better awareness and good experience of getting high productivity of honey. Thus, the overall beekeepers practice of using modern beehives had a significant difference (P<0.001) among the three agro ecologies.

Honey productivity

As shown in Table 9, the overall average honey productivity per beehive in traditional, transitional and modern beehives throughout the three agro-ecologies was 10.16 ± 00.45 kg, 13.61 ± 0.23 kg and 23.32 ± 0.569 kg, respectively. Similar, results were reported by Getu and Birhan [17] and Kinati et al. [7] as the average honey yield per year/beehives was 7.20 ± 0.23, 14.70 ± 0.62 and 23.38 ± 0.73 kg for traditional, transitional and modern beehives, respectively. However, it is above the average amount of honey harvested from traditional, transitional and modern beehives: 5.22 kg, 10.83 kg and 15.2 kg per beehives, respectively as reported by Beyene and Verschuur [11]. The minimum and maximum honey productivity of the current study from modern hives was 15 kg to 50 kg per beehive. The result was in agreement with previous findings of Yirga and Mekonen [15] reported as the potential productivity (the maximum yield) of the modern beehives was (45-50 kg/beehives) higher than the traditional beehives.

| Variables | Min | Max | Study area | Over all | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Land | Mid Land | Low Land | N=332 | ||||

| N=165 | N=105 | N=62 | |||||

| Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | ||||

| Traditional (kg) | 5 | 50 | 8.90 ± 0.63 | 10.53 ± 0.82 | 12.89 ± 1.02 | 10.16 ± 0.46 | * |

| Transitional (kg) | 8 | 30 | 12.93 ± 0.24 | 13.28 ± 0.39 | 16.00 ± 0.77 | 13.61 ± 0.23 | *** |

| Modern hives (kg) | 15 | 50 | 25.62 ± 0.91 | 21.89 ± 0.83 | 19.63 ± 1.00 | 23.32 ± 0.57 | *** |

| Price colonies (ETB) | 500 | 2500 | 973.33 ± 37.9 | 973.33 ± 41.5 | 912.90 ± 60.2 | 930.42 ± 25.6 | 0.22NS |

| Prices of one transitional beehives (ETB) | 100 | 120 | 105.45 ± 0.61 | 105.90 ± 0.85 | 103.39 ± 0.87 | 105.21 ± 0.44 | 0.21NS |

| Prices of one modern beehives (ETB) | 1000 | 1500 | 1116.06 ± 15.4 | 1228.57 ± 17.5 | 1175.41 ± 22. | 1187.61 ± 10.4 | *** |

| Frequency of honey harvest per annum of traditional hives | 1 | 3 | 2.54 ± 0.43 | 2.03 ± 0.85 | 1.82 ± 0.102 | 2.24 ± 0.43 | * |

| Frequency of honey harvest/yrs of transitional hives | 1 | 2 | 1.33 ± 0.037 | 1.27 ± 0.43 | 1.10 ± 0.038 | 1.27 ± 0.024 | 0.34NS |

| Frequency of honey harvest per annum of modern hives | 1 | 2 | 1.19 ± 0.031 | 1.27 ± 0.04 | 1.23 ± 0.054 | 1.22 ± 0.023 | *** |

*Significance at p<0.05%; ***Significant at p<0.001; NS: Non-significant at p>0.05; N: Number of respondents; SE: Standard Error.

Table 9: Honey yield, cost of beehives and bee colony and harvest frequency.

Yield harvesting frequency

As reported by the beekeepers the minimum and maximum frequency of honey harvesting per annum of the traditional, transitional and modern hives were: 1 and 3, 1 and 2, 1 and 2, respectively (Table 9). This result is comparable with Kebede and Tadesse [18] who reported that honey can be harvested once or twice, while in some cases even three times in a year largely depending on the availability of bee forage. Comparatively, there was low frequency of honey harvested in modern beehives because of the large size and volume of beehives that bees could not fill the beehive within a short period of time and short duration of rainy fall season as well as lack of pure bee wax’s, pest and predators (wax mouth). The frequency of honey harvest was more in the highland area than other two agro-ecologies due to the availability of different bee forage, honeybee colonies, availability of water due to sufficient rain fall distribution that continued raining from four to five months, conductive weather condition for bees etc. However, in the low land areas that leads to low frequency of honey harvest per annum in all the three types of honey (traditional, transitional and modern beehives) (Figure 1).

Household income from bee keeping practice

As indicated in Table 10, beekeepers reported as they got revenue from different types of beekeeping practice such as income from selling crude honey, crude bees wax’s and from the sale of bee colonies. According to beekeepers response, the average annual income per household from selling the crude honey was 4,092.90 ETB. There was significant difference (P<0.05) among the three agro-ecologies in earning income from selling crude honey. Beekeeper also reported as they earned income from the sale of crude bees wax’s and bee colonies on the average income of 383.28 and 1462.35 ± 47 ETB per household, per annum, respectively.

| Variables | Min | Max | Study area | Over all | P –value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL (N=165) | ML (N=105) | LL (N=62) | N=332 | ||||

| Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | ||||

| Household income for sale of crude honey | 1600 | 15750 | 4398.18 ± 30 | 4117.14 ± 26 | 3237.90 ± 365 | 4092.90 ± 185 | 0.07 |

| Household income for sale of crude bees wax | 300 | 1000 | 388.48 ± 13 | 376.67 ± 15 | 380.65 ± 21 | 383.28 ± 9 | 0.839 |

| Household income for sale of bees colonies | 500 | 3500 | 1363.64 ± 60 | 1576.26 ± 92 | 1532.26 ± 120 | 1462.35 ± 47 | 0.11NS |

| Prices of white honey | 150 | 200 | 163.09 ± 1 | 163.90 ± 1 | 163.23 ± 2.52 | 163.37 ± 0.89 | 0.921 |

| Prices of red honey | 60 | 160 | 96.24 ± 2.6 | 78.86 ± 2.48 | 67.26 ± 1.058 | 85.33 ± 1.661 | ** |

| Prices of mixed honey | 80 | 180 | 108.48 ± 2.3 | 112.67 ± 3.4 | 107.42 ± 4.35 | 109.61 ± 1.81 | 0.5NS |

| Prices of yellow honey | 70 | 160 | 92.00 ± 1.72 | 84.76 ± 1.54 | 90.65 ± 3.27 | 89.46 ± 1.17 | * |

* Significance at p<0.05%; ** Significance at p<0.01; NS: Non-significant at p>0.05; N: Number of respondents; SE: Standard Error; HL: Highland; ML: Midland; LL: Lowland.

Table 10: Household income and prices of crude honey in color (Ethiopian birr).

Trend in the number of colonies and honey production over five years

The overall trend of bee colonies has been reduced in number from 2012 to 2016 years as indicated in Figure 2. The number of honeybee colonies in all types of beehive (traditional, transitional and modern honeybee colonies) has been decreased from 5614 honeybee colonies in 2012 to 2452 honeybee colonies in 2016 years with a radical reduction in number of honeybee colonies due to different challenges such as: drought, pest and predator etc. The current result is similar with Beyene and Verschuur [11] reported that out of the total respondents, about 67% beekeepers were replied as honey yield has decreased continuously due to different challenges such as deforestation, agrochemical application, pest and predators etc.

Trend of honey production and productivity over five years (2012-2016/17)

The overall trend of honey production in Waghimara Zone was declined throughout the five consecutive years from 2012 to 2016 as indicated in Figure 3. The overall average honey production of the three types of beehives was 59541.5 kg in 2012 but it was reduced to 29973.5 kg in 2016 due to different challenges such as: consecutive drought, lack of bee forage associated with deforestation, pest and predators, shortage of water etc., as the beekeeper replied. However, the lowest honey production was recorded in 2015 compared to other four years, which was 19319 kg with down ward shift of the graph due to extreme drought that lead to shortage of bee forage, water, death of bee colonies and being attacked easily with pest and predators. This result is comparable with previous findings Beyene and Verschuur [11] as they reported as when rain fall season is good, there is ample pollen and nectar source of bee forage in the area. In addition, the amount of honey produced in such season is high but if the dry season prolonged, there is shortage of bee forage availability in the area. In this season, the amount of honey harvested is very low. To sum up, the bee colony and honey production trend have been declining over the five years due to various challenges.

Inspection of honeybee colonies and apiary site

As shown in Table 11, beekeeper reported as they conducted external and internal beehive colony inspection. Large number of beekeepers 30.4% reported as they conducted inspection some times, 23.7% rarely, 19.9% monthly, 13.3% weekly, 7.8% and only 4.9% made inspection on their bee colonies daily. Therefore, most of the beekeepers did not conduct external inspection frequently on their beehive colonies due to lack of awareness and lack of giving priority to beekeeping practice rather they considered as a source of alternative income source. This result was in agreement with Kinati et al. [7] as they reported that farmers in Ethiopia don’t commonly practice internal hive inspection due to the difficult of the traditional hives for internal inspection i.e., fixed combs attached to the body of traditional beehive.

| Category | Variables | Frequency of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| (N=332) N (%) | ||

| External-inspection | Daily inspection | 16 (4.9) |

| 2-3 days inspection | 26 (7.8) | |

| Weekly inspection | 44 (13.3) | |

| Monthly inspection | 66 (19.9) | |

| Sometimes inspection | 101 (30.3) | |

| Rarely | 79 (23.7) | |

| Internal inspection | Daily inspection | 1 (0.3) |

| 2-3 days inspection | 5 (1.5) | |

| Weekly inspection | 13 (3.9) | |

| Monthly inspection | 46 (13.9) | |

| Sometimes inspection | 107 (32.2) | |

| Rarely | 160 (48.2) |

Source: Field survey, December-March, 2016/17; N: number of sampled respondents.

Table 11: Experience of beekeepers apiary site inspection.

Regarding internal inspection of their bee colonies, large number of beekeepers 48.2% of them reported as they inspected rarely whereas 32.2% of them some times, 13.9% monthly, 3.9% weekly and a few number of beekeepers 1.5% made inspection within 2-3 days and only 1 respondent 0.3% conducted daily inspection (Table 11). This result agrees with Kebede and Tadesse [18] who stated that the majority (53.8%) of the respondents replied that they inspect hives some times. Similarly, Birhan et al. [19] reported that, hive inspection by opening the hive is not a common practice. Internal hive inspection is undertaken by not more than 20% of beekeepers.

Experience of bee keepers in supplying supplementary feed and water for dry season

As reported by bee keepers honeybee feed shortage occurred mainly during January to May (65.7%) followed by February to August (23.9%), June to August (7.5%) and September to January (2.9%). To address this challenge, beekeeper replied as they provide supplementary feed in the dry season such as: basso, shiro, sugar syrup, honey and water as well as grain flour as indicated in Table 12. During dry period, 47.59% of the respondents provide supplementary feeds to their bee colonies [20].

| Category | Variables | Frequency of the |

|---|---|---|

| respondents (N=332) | ||

| N (%) | ||

| Supplementary feeding of honeybees for dry season | Basso | 17 (10.8) |

| Shiro | 21 (13.3) | |

| Sugar syrup | 33 (20.9) | |

| Honey and water | 20 (12.7) | |

| Grain flour | 67 (42.3) | |

| Over all | 158 (47.59) | |

| Sources of water for honeybees | River | 84 (25.3) |

| Well | 73 (22.0) | |

| Ponds | 50 (15.1) | |

| Streams | 48 (14.5) | |

| Lakes | 17 (5.1) | |

| Water harvest structure | 34 (10.2) | |

| Taps water | 26 (7.8) | |

| Honeybee colonies | Occurrence of migratory beekeeping practice in the study area | |

| Yes | 74 (22.3) | |

| No | 258 (77.7) | |

| Reason for bee colonies migratory practice | ||

| Fetch of forage and water | 41 (55.4) | |

| Honey production | 33 (44.6) |

Source: Field survey, December-March, 2016/17; N: Number of sampled respondents.

Table 12: Sources of water, dry season feeding and honeybees migratory practices.

In most cases, external and mass feeding was exercised by the beekeepers. The most commonly used supplementary feeds include; 42.3%, 20.9%, 13.3%, 12.7% and 10.8% of the beekeepers provide grain flour, sugar syrup shiro, honey and water, and basso, respectively.

In addition, to mitigate the shortage of feed for their colonies 22.3% of beekeepers reported as they plant bee forages around their apiary site whereas some of them leave some amount of honey un-harvested for the dry period. In supporting this result, Gebru [13] reported that supplementary feeding and migratory beekeeping practice were conducted to overcome the feed shortage at dry season. For instance, beekeepers they gave besso, shiro, flour, sugar syrup and honey with water mainly from February to May.

Incidence of swarming and controlling methods

In the study area, about 90.9% of the beekeeper reported as there were an incidence of reproductive swarming during the study year (2016/17), the different causes of swarming were reproductive activities (41.9%), presence of drones and queen cells (29.2%) and an overcrowding of the nest (25.9) in descending order as indicated in Table 13. This result agrees with the previous findings as 95% reacted occurrence of reproductive swarming in their apiary with the remaining about 5% had no known swarming [6].

| Parameter | Variables | Frequency of the |

|---|---|---|

| respondents (N=332) | ||

| N (%) | ||

| Swarming Activities | ||

| Occurrences of swarming | Yes | 301 (90.9) |

| No | 31 (9.1) | |

| Cause of swarming activities | Reproductive activities | 139 (41.9) |

| Presence of drones and queen cells | 96 (28.9) | |

| Overcrowding of the nest | 97 (29.2) | |

| Frequency of swarming | Every season | 26 (7.8) |

| Every years | 245 (73.8) | |

| Once two years | 61 (18.4) | |

| Swarming advantage to beekeepers | To increase number of bee colonies | 143 (43.1) |

| Income activities | 74 (22.3) | |

| To replace non-productive bee colony | 115 (34.6) | |

| Swarming prevention | Yes | 266 (80.1) |

| No | 66 (19.9) | |

| Swarming control methods | Return back of the colony | 99 (29.8) |

| Removal of queen cells | 103 (31.0) | |

| Cutting comb | 29 (8.7) | |

| Seasonal super | 57 (17.2) | |

| Using large volume hives | 28 (8.4) | |

| Other traditional methods | 16 (4.8) | |

| Absconding activities | ||

| Occurrences of absconding | Yes | 303 (91.3) |

| No | 29 (8.7) | |

| Reason of absconding | Drought | 66 (19.9) |

| Pest and predators | 110 (33.1) | |

| Shortage of feed and water | 67 (20.2) | |

| Poor management | 38 (11.4) | |

| Pesticides and herbicides | 51 (15.4) | |

| Frequency of absconding | Every season | 29 (8.7) |

| Every years | 54 (16.3) | |

| Once in to two years | 119 (35.8) | |

| Once 3-5 years | 130 (39.2) | |

Source: Field survey, December-March, 2016/17; N: Number of sampled respondents.

Table 13: Activities of swarming and absconding in the study area.

The swarming time of honeybee colonies in the study was from July to October whereas its peak time occurrence was from August to September. During this peak period, beekeepers became very busy and active in order to prevent and control swarming. Regarding the frequency of swarming, most 73.8% of beekeepers reported as it occurred in every years where as 18.4% of them reported as it occurred once in two years and small number of beekeepers 7.8% gave their response as swarming occurred in every season as illustrated in Table 13. In addition, the primary swarm consists of the old queen to gather with about 60% of workers (up to 4500 bees), and will often leave the hive prior to the emergence of the first new virgin queens. Large colonies may produces secondary “after swarms” and in this way successful hive may split more than once in a given year initially, the swarm will alight in a temporary location not far from the original colony swarming has various advantageous to beekeepers such as: to increase number of bee colonies (43.1%), source of income (34.6%) and to replace nonproductive bee colonies as (23.3%) of respondents replied [21,22].

Swarming has an advantage for beekeepers because honeybee colonies are very important sources of income since it could be sold at satisfactory price (up to 1462ETB/colony). On the other hand, swarming control is essential in honey production and pollination at optimum strength and it has different controlling methods as most of beekeepers (80.1%) of them confirmed in their response whereas the rest (19.9%) respondents did not have any swarming control methods. Relatively large number of beekeeper respondents (31.0%) replied as they used removal of queen cells whereas (29.8%) of them used return back of the colony and (17.2%) respondents used seasonal spurring as swarming controlling methods [23]. In addition, beekeepers used swarm controlling methods like cutting comb using large volume beehives and other traditional methods as indicated in Table. In supporting, the above stated finding, Belie [12] found in this study conducted at Bure district that the most frequently ways of controlling reproductive swarming were removal of queen cells (46.2%), killing queen of the swarm and returning of honey bee colony to its Mather (28.2%), etc.

Incidence of honeybee colony absconding

Absconding is another swarming activity pattern and it is not reproductive mechanism out purely a survival device and caused by drought, pest and predators, shortage of feed and water, poor management, pesticides and herbicides, etc. [24]. The majority (91.3%) of beekeepers responded as there was the occurrence of absconding in the study areas due to pest and predators (33.1%), shortage of feed and water (19.9%), pesticides and herbicides (15.4%), and poor management (11.4%) were the major causes of absconding in a descending order. As shown in Table 13.

The result also supported by study of Kinati et al. [7] which reported consequently bees leave their site for another or abandoned their hives at any season of the year for different reasons such as: lack of forage, incidence of pest and predators, during harvesting, sanitation problem, bad weather condition and bee diseases. Regarding the frequency of absconding, large number respondents (39.2%) of them confirmed as it occurred once in 3-5 years whereas (35.8%) of beekeepers replied as it occurred in every season. However, the finding of Beli [12] revealed that absconding occurred at any season of year in Bure districts which is unlike with this finding might be due to lack of bee forage, pest and predators, bee poisoning, etc.

It can be concluded that beekeeping in Abergell, Sekota and Gazgibala districts contribute a great deal to the household welfare in terms of income generation. Beekeeping activities in the study area is the third income generation tasks next to crop and livestock production. The area is suitable for honeybee production because of availability of honeybee colony, different bee forages in different season and better experience in rearing beekeeping. An increase in honeybee colony and honey price triggers the farmers to participate in this sector. However, the majority of beekeepers in study area did not use improved beekeeping technologies instead, they practiced traditionally. Most beekeepers have limited attention for different operational beekeeping activities. Most of the beekeepers don’t provide supplementary feed for honeybee colony in dry seasons. Moreover, consecutive drought, lack of bee forage associated with deforestation, prevalence of pest and predators, shortage of water, poor farmers awareness and indiscriminate agrochemical utilizations, shortage of beekeeping equipment were reported by the respondent households as the most important constraints of honey production in the districts. Due to this challenge the overall trend of bee colony and honey production has been declining from 2012 to 2016 in all types of beehives. Based on the results of this study, the following recommendations are forwarded for improving beekeeping practice and honey production activities in the study areas.

• In order to prevent pest and predators, clearing apiary site and conducting continuous hive inspection is important.

• The awareness of the farmers should be improved by different training activities and it essential to establish strong linkage between the farmers, the development agents and the research institutions.

• Providing sufficient beekeeping equipment’s and credit also increases the farmers involvement in beekeeping practices.

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to all staff of Abergell, Sekota and Gazgibala district and Waghimera Zone Livestock and Fisheries Resource Department for providing the necessary baseline data for this study. Similarly, we would like to appreciate and acknowledge the farmers who participated in the survey and focus group discussions, Development Agents working in the study areas for their critical support in data collection.