Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-9600

ISSN: 2155-9600

Research Article - (2023)Volume 13, Issue 6

Introduction: Malnutrition is a complex problem related to various factors and there is need for nutrition specific interventions as well as nutrition-sensitive programs, the latter through a multi-sectoral approach. Global experience and evidence show that improvements in nutrition security will require a multi-sectorial and coordinated response. One of the five objectives of national nutrition program II for malnutrition reduction in Ethiopia is multisectoral nutrition coordination. To implement this objective effectively, there is a designed coordination mechanism from national up to community level.

Experiences of multisectoral collaborations from South America, Asia, Africa and Europian region showed that the most important barriers to multisectoral, implementation were poor political commitment, poor communication among key individuals and sectors, lack of political, financial and administrative accountability.

Methods: Qualitative study design has been used with semi structured open ended questions to collect information from woredas key informants and kebeles focus group discussion participants. Framework data analysis approach has been used with all five stages.

Results: The result showed multisectoral nutrition coordination program was not properly coordinated on both woredas. The key challenges identified on both districts were absence of regular monitoring and evaluation, lack of communication, absence of accountability mechanisms, structural problem and lack of line item budget specific for coordination activities.

Conclusion: From findings of both districts, multisectoral nutrition interventions are not effectively coordinated in both districts. Over the past years, the integrated supportive supervision, review meeting, regular report, feedback mechanisms and program evaluation were poorly coordinated at each level.

Malnutrition; Communication; Evaluation; Political commitment; Community

Malnutrition is a complex problem related to various factors and there is need for nutrition specific interventions as well as nutrition-sensitive programs, the latter through a multi-sectoral approach. Strong political commitment, multi-sectoral collaboration, community based service delivery platforms and wider program coverage and compliance are all likely critical components of effective stunting reduction programs in low and middle income countries.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide an important opportunity to more fully realize the potential of multisectoral action for health. There is a need for the development of a clear implementation research agenda on the governance of multisectoral action, which could provide a rallying point for a community of learning and practice and should be explicitly supported by global institutions.

The need for cross-sector collaboration was outlined in the publication of the USAID 2014-2025 multisectoral nutrition strategy, which states that “multisectoral coordination along with collaborative planning and programming across sectors at national, regional, and local levels are necessary to accelerate and sustain nutrition improvements.

One of the five objectives of NNPII for malnutrition reduction in Ethiopia is multisectoral nutrition coordination. To implement this objective effectively, there is a designed coordination mechanism from national up to community level through National Nutrition Coordination Body (NNCB) and multi-sectoral Nutrition Technical Committee (NTC).

Every country is facing a serious public health challenge from malnutrition. The economic consequences represent losses of 11 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) every year in Africa and Asia, whereas preventing malnutrition delivers $16 in returns on investment for every $1 spent.

The risk of stunted growth and development is influenced by the context in which a child is born and grows. This context is multisectoral, and includes the political economy, health and health care, education, society and culture, agriculture and food systems, water and sanitation, and the environment.

Ethiopia has one of the highest rates of malnutrition in Sub- Saharan Africa, and faces acute and chronic malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies. Nutrition deficiencies during the first critical 1,000 days (pregnancy to 2 years) put a child at risk of being stunted and affect 38% of less than five years children in Ethiopia.

The total losses associated with under nutrition in Ethiopia is estimated at ETB 55.5 billion, or $US 4.7 billion for the year 2009. These losses are equivalent to 16.5% of GDP of that year. The highest element in these costs relates to the lost working hours due to mortality associated with under nutrition.

Experiences of multi-sectoral collaborations from South America, Asia, Africa and Europian region showed that the most important barriers to multi-sectoral, implementation were poor political commitment, poor communication among key individuals and sectors, lack of political, financial and administrative accountability, lack of building indicators and methods for monitoring and evaluation and supporting relevant research.

From the study conducted in Ethiopia and Nepal on implementing multi-sector nutrition programs, challenges and opportunities were identified from stakeholder perspectives: Effective coordination is identified as a major concern in both countries, although the relative magnitude varies. In Ethiopia, no process buy in, no line item budget and the need for coordination were key challenges.

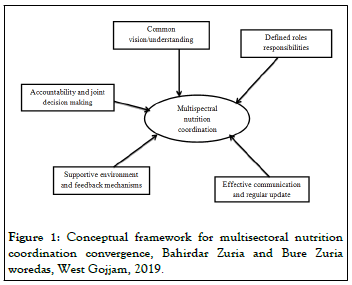

The first phase of NNP (2008-2015) of multi-sectoral nutrition coordination body and technical committee were in effective due to lack of clarity on coordination mechanism, the absence of an implementation guideline, lack of dedicated implementation personnel at sector level, and lack of established reporting mechanisms using clear and measurable indicators, therefore not in a position to accelerate and engage in implementing, monitoring and evaluating the progress of the national nutrition program. Based on the identified gaps, second phase National Nutrition Program (NNP II) has been designed by incorporating multisectoral nutrition coordination as one of the objectives in such a way that can avoid previous implementation gaps with suitable government structures. This study aims to explore specific challenges and opportunities for the implementation of second phase multisectoral nutrition coordination on the study areas (Figure 1) [1-3].

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for multisectoral nutrition coordination convergence, Bahirdar Zuria and Bure Zuria woredas, West Gojjam, 2019.

Study design

Qualitative study design has been used to identify the challenges and opportunities of multisectoral coordination functioning. Data collection follows three approaches such as existing document review, key informant interview with individuals who have specific understanding about the situation and focus group discussion with nutrition committee members and community representatives.

Study area and sampling

This study was conducted in Amhara regional state, West Gojjam zone, where the regional stunting prevalence among fewer than five years children is very high with in a country.

Woreda nutrition coordination body and nutrition technical committee members from health, agriculture and education sectors and kebele nutrition committee members from Bure Zuria and Bahirdar Zuria were studied. Additionally community representatives were part of the study participants.

Selection procedure of study woredas and kebeles

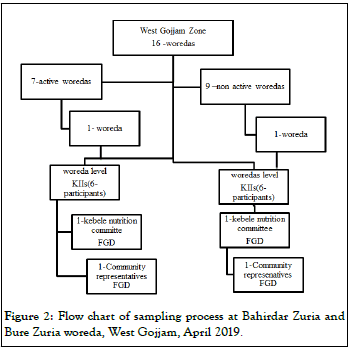

There are 16 woredas in West Gojjam zone, which are implementing multisectoral nutrition intervention and all woredas were eligible for sampling. By communicating with zonal health department about woredas communication, documentation and reporting with zonal technical committee, weredas were categorized as active and non-active.

To avoid the selection bias, active and non-active woredas were separately categorized. One woreda from active and one from non-active woredas were selected randomly. Study kebeles were selected based on geographical accessibility for transport purpose and kebele nutrition committee and kebele representatives Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) has been conducted on the same kebele (Figure 2) [4,5].

Figure 2: Flow chart of sampling process at Bahirdar Zuria and Bure Zuria woreda, West Gojjam, April 2019.

Data collection

Data collection has been conducted with principal investigator and two assistants to facilitate the data collection process recruited from zonal health department who have previous data collection experiences. Data collection was conducted with the following three approaches.

Document review

Documents dated between July 2017 and June 2018 were reviewed by direct observation in person at Bure Zuria and Bahirdar Zuria woredas. The documents reviewed were the availability of guidelines, joint plans, joint monitoring and review, role and responsibility descriptions, meeting minutes and training materials.

Key informant interviews

The key informants were sectoral heads which are the members of coordination body and technical committee members who are focal points of health, agriculture and education sectors of both woredas. Interviews were conducted in a private space and interviews were conducted in Amharic which was translated from first version of English language questionnaire. The researcher obtained written consent from the study participants at the time of the interview.

With participant permission granted, all interviews were audio recorded in addition to take notes. An interview guide specifically developed for this study was used and all informants were asked the same questions.

Focus group discussion

The participants of Focus Group Discussion (FGD) were from two kebeles nutrition committee members and from two kebeles community representatives. Kebele nutrition committee members were from kebele administrators, kebele executive officers, health extension workers, agriculture development agents, school directors, women leagues and youth leagues representatives. Community representatives were from pregnant women, lactating women, HDA leaders, 1 to 5 leaders, farmers and community leaders. An interview guide also prepared for both groups to facilitate discussions.

Data management

After collecting the required data, interview text and audio recorded documents were stored and saved into folders by type of document. Following each interview, the text and audio recordings were labeled with a short code for participant category, committee membership, and date of interview, start and end time of interview and audio recording number. The researcher then translates to English language and transcribed the digital recordings following the interviews and expands the interview notes.

Data analysis

Framework analysis approach was used by following all five stages. Familiarization (whole or partial transcription and reading of the data), thematic framework (initial coding framework), indexing/coding (the process of applying the thematic framework to the data, using numerical or textual codes to identify specific pieces of data which correspond to differing themes), charting (using headings from the thematic framework to create charts for easily read across the whole dataset), mapping and interpretation (searching for patterns, associations, concepts, and explanations in the data). Subsequent to transcribing and conducting an initial read of the interview transcripts, open code 4.02 qualitative data analysis software was used.

Description of study participants

Data has been collected from total of 12 key informants from Bahirdar Zuria and Bure Zuria woreda nutrition coordination body and nutrition technical committee members of health, agriculture and education sectors and equal number of participants were involved from both woredas. Additionally 17 kebele nutrition committee FGD participants and 18 community representatives Focus group discussants were also included from Wondata kebele of Bahirdar Zuria and Shakoa kebele of Bure Zuria woreda. The time of key informant interviews and FGD conducted was determined up on reaching the saturation point where no more new emerging ideas come from the participants (Table 1) [6].

| Characteristics | Bahirdar Zuria | Bure Zuria |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 20-30 | 10 | 12 |

| 31-40 | 10 | 9 |

| 41-50 | 2 | 2 |

| >50 | 1 | 1 |

| Sub total | 23 | 24 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 12 | 10 |

| Female | 11 | 14 |

| Sub total | 23 | 24 |

| No.of KII participants | 6 | 6 |

| No.of Kebele committee FGD participants | 9 | 8 |

| No. of community representatives FGD participants | 8 | 10 |

| Sub total | 23 | 24 |

Table 1: Summary of description of study participants Bahirdar Zuria and Bure Zuria woredas, 2019.

Functional features of existing multisectoral coordination mechanisms

Theme 1: Current status of multisectoral coordination mechanism

Category 1: Common understanding: Concerning the knowledge of overall program coordination mechanisms 83% of KII participants had a knowhow on multisectoral nutrition coordination program implementation objectives, indicators and its importance. But, both kebele nutrition committee focus group discussion participants had no clear information on multisectoral nutrition program implementation, only health extension workers, school director and agriculture development agent have orientation at Bahirdar Zuria woreda and only HEWs have orientation and clear information on multisectoral nutrition coordination activities at Bure Zuria woreda.

Regarding kebele nutrition committee functionality, all 32 kebeles at Bahirdar Zuria and all of 20 kebeles at Bure Zuria established the committee. Even though there is a different level of understanding on kebele nutrition coordination activities among KII participants of both woredas. Since there was no active involvement of stakeholders on kebele committee establishment except health sector, most of KII participants had no clear information about the responsibilities of kebele committee.

Category 2: Roles and responsibilities sharing: Nutrition Coordination Body (NCB) and Nutrition Technical Committee (NTC) are established at woreda and kebele level in both woredas based on national arrangement with the involvement of participants from multisectors. In both study areas there was no TOR document which contains clear roles and responsibilities and also no accountability monitoring mechanisms in place except joint planning at the beginning of the year at both woredas.

Kebele committee FGD participants of both woredas said that no responsibility shared among the committee members. The committee simply formed with the coordination of HEWs and then after nothing has been done to us said the committee member of both woredas. Nutrition activities are just considered the responsibility of health sector said both kebele committee members.

Poultary promotion and fruit and vegetables gardening activities are not integrated with multisectoral nutrition intervention activities at household and schools at both woredas according to the key informants and kebele committee focus group dicussion participant’s response. The community participants of both woredas also stated that no fruit and vegetables grown and no poultry promotion practiced for the purpose of malnutrition prevention at household level due to lack of awareness on their importance.

Community representative focus group discussion participants also support the idea that there were no integrated activities coordinated by kebele nutrition committee. They explained only nutrition specific activities like iron folic acid supplementation, vitamin A supplementation, growth monitoring and nutrition counseling activities provided by health extension workers and health workers at their community. They also stated that there are no regular nutrition awareness creation activities with local media and government channels in their community except counseling services at health facilities.

Category 3: Horizontal and vertical communication: There was no horizontal and vertical communication with phone and email on status update at both woredas. But one time Nutrition Coordination Body (NCB) and one time Nutrition Technical Committee (NTC) meetings has been conducted at Bahirdar Zuria and one time Nutrition Coordination body (NCB) and seven times nutrition technical committee meetings have been conducted at Bure Zuria woreda during 2010 E.C. even though two meetings and four meetings are expected for nutrition coordination body and technical committee respectively based on the guideline [7].

Except one time program orientation there is no regular updates and capacity building activities on effective coordination activities at each level agreed all participants of both woredas. Only one zonal NCB supportive supervision conducted during last year at Bahirdar Zuria woreda but both woredas NCB and NTC did not conduct supportive supervision and review meeting on kebele nutrition interventions said all the respondents. Even there was no report and feedback activities from zonal to kebele level during last financial year agreed all respondents. The score card and checklist monitoring tools developed for NNP implementation activities are not practiced yet on both woredas.

There was no data on the participation rate of mothers and health development armies who were participated on cooking demonstration at both wordas since there is no formal reporting system on this activity.

One participants of key informant said that “currently multisectoral nutrition acivities are less priority because as we can observe from our experience priority activities from higher level can be performed well” (health sector).

The above verbatim clearly showed that, currently health and nutrition activities on health system are not implemented based on the plan, rather focused on higher officials priority, donor based and campaign based.

There was no joint meeting, planning, monitoring and evaluation and reporting of nutrition specific and nutrition sensitive interventions at kebele level except one time meeting of kebele committee at Bure Zuria woreda.

Theme 2: Infant and young child feeding practice at community

Category 1: Knowledge on 1000 days: Regarding the knowledge and practice of infant and young child feeding of community members, only four of the 18 (22.2%) community representatives focus group discussion participants heard about 1000 days , from those four participants only two of them (11.1%) explained well the periods and interventions of 1000 days from both kebeles.

Concerning the initiation of breast feeding after birth, there were different opinions from the participants. Some participants said early initiation of breast feeding is after 2 hours, some of them said after one hour and some of them said started immediately after birth if the mother is well. But no one can state the benefit of colostrum feeding even though most of the mothers at community do not remove colostrum. However, clostrum feeding was not for the sake of child benefit rather due to community believes.

One participant mother of 8 months infant said that “there is a traditional believe at community that, if we remove colostrum, breast milk will not be produced and that is why we do not remove it”.

Category 2: Infant and young child feeding practices: Both woredas community representative participants were agreed that complementary feeding started after six months of age even though introducing pre-lacteal feeding like water and cow milk before six months of age is still a problem at Bure Zuria woreda

The respondents mentioned that lack of knowledge and poor mother and child care practice at rural community are contributing factor for malnutrition.

One participant said “that lactating mothers at rural community cannot have even adequate rest; just start their routine activities immediately with in few days after delivery’’.

Although Health Development Army (HDAs) are trained on complementary food cooking demonstration at both districts, no regular monthly cooking demonstration at both districts of the community. Only 10 of 32 (31%) kebeles at Bahirdar Zuria conducted with community contribution and 5 of 20 (25%) kebeles conducted the monthly demonstration at Bure Zuria woreda on regular bases with woreda and partners food items assistance. “One health extension worker explained that even though community contribution is expected on food items for cooking demonstration, Still there is poor community ownership, it is conducted by contribution of food items from health center and agriculture sector” [8].

Challenges of existing multi-sectoral coordination mechanisms

Theme 3: Challenges of existing multisectoral nutrition coordination mechanisms

Category 1: Absence of clear role and responsibilities sharing: Even though both woredas were assigned focal person, there was no clear role and responsibility details documented and provided for each sectors. Both districts participation in coordination activities was not obligatory, the health sector was the only committee member for initiating meetings and doing nutrition specific activities included in his/her job description. Due to the absence of documented responsibility sharing on study areas, education and agricultural sectors multisectoral activities like nutrition education, school gardening, house hold gardening practices and poultry production were not practical.

School and house hold gardening programs aim at teaching students and farmers on how to make a garden to ensure diversified food diet and poultry promotion is critical for feeding of egg for young children. In the contrary on both woredas gardening and poultry activities were not practical due to lack of proper planning and clear responsibility sharing.

Category 2: Lack of effective communication and regular update: Multisectors collaboration activities relies on effective communication platforms (regular meeting, phone and mail communications. this information can inform decisions, facilitate needed changes in real time, and guide future efforts. The finding from both woredas showed that there was no phone and mail communications with both coordinating body and technical committee. There was irregular meetings at woreda level and no meetings at all on both kebeles. In addition there were no regular technical updates on ongoing activities for committee members. As a result of lack of communication and regular updates, there was variability of knowledge among committee members besides lagging of planned activities up to community level. because of staff turnover with in multisectors, the newly assigned focal person were not provided technical update on coordination activities and this gap also described as a challenge by key informants. Both kebele committee participants response underlined the absence of communication with their respective woredas regarding nutrition sensitive and nutrition specific interventions at community level. Community representative FGD respondents also strengthened the ideas about the absence of communication with kebele committee about house hold gardening, poultry production and cooking demonstration activities.

Category 3: Absence of accountability and commitment: Collaboration requires resources, time, and committed person to initiate and maintain efforts over time. This can be true when accountability mechanisms clearly indicated on coordination activities at each level. But this study finding clearly showed that there was no terms of reference prepared that consists detailed responsibility and accountability issues. Due to the absence of accountability mechanisms in place, expected deliverables like functional woreda and kebele committee, regular communication, periodic supportive supervision and review meetings were not properly coordinated at woreda and kebele level. As a result of absence of accountability mechanisms in place, lack of commitment among committee members for active involvement on multisectoral nutrition interventions also clearly stated by respondents. Because no one is accounted for inefficiency and at the same time, there was no incentives/ reward mechanism for good performer. Therefore absence of accountability contributed for coordination efforts are not possible and cannot encourage sectoral focal person to ensure commitment to the time and effort required for collaboration.

Category 4: Lack of monitoring and evaluation mechanisms: Monitoring and evaluation of collaboration activities is important to recognize participants’ efforts and to demonstrate that the time, energy, and money invested contribute to objectives. Monitoring and evaluation on collaboration will help multisectors implement the efforts, know if activities are on track, and determine if implementation approaches need to be revised. However, measuring collaboration was challenging due to a lack of well-coordinated monitoring and evaluation activities and absence of report and feedback mechanisms on both woredas. The respondents stated that there was no supportive supervision and review meeting and reporting on multisectoral nutrition coordination activities during 2010 financial year on both woredas even though quarterly supportive supervision and review meetings are expected. The respondents’ also added that poor monitoring and evaluation at woreda level was the result of the absence of support and monitoring and evaluation from regional and national governments. Even though the monitoring tools like scorecard and checklists were clearly indicated in the implementation guide, both woredas were not totally used these tools. The absence of supportive supervision from their respective woredas was also stated by both kebele committee members. The committee members said that regular support can be helpful for understanding multisecoral nutrition intervention at kebele level, since most of the members were not aware about the objectives of multisectoral nutrition interventions and expected roles and responsibilities of each member. The absence of monitoring and evaluation clearly showed the discrepancy of planed activities with performance at woreda and kebele level.

Category 5: Lack of budget: For successful integration of multisectoral nutrition interventions, it requires careful planning, including development of budgets and allocation of sufficient funding and resources. To facilitate the financial and budgetary aspects of multisectoral nutrition integration, the government of Ethiopia clearly indicated sustainable financing plan in multisectoral nutrition coordination guideline. But even though the gross budget for five years NNP plan was documented on the guideline, there is no clear guidance and accountability document cascaded at woreda level about budget allocation. The guideline simply indicates sectors are responsible for budgeting. Because of the lack of clear accountability; budget allocation was depend on the good will of the government officials. They are not accountable whether they allocate or not. On both study woredas, there was no allocated budget for multisectoral nutrition activities. woreda technical committee key informants said that their sectors were not voluntary to facilitate budget for kebele committee support. Key informants also added that sectoral heads perceived that health sector should be responsible to allocate budget for nutrition interventions. Kebele nutrition committee participants also stated that because of unavailable budget for multisectoral nutrition intervention at woreda level, there was no awareness creation activities, no supportive supervision and review meetings facilitated by woredas to strengthen nutrition interventions at kebele level.

One of the HEW said that ”I heard that the budget source of most of the review meetings are nutrition projects, so why not the health sector focused on the direct program implementation like multisectoral nutrition activities instead of wasting the money for other programs”.

Therefore the study findings clearly showed that obtaining sustainable financial resources for multisectoral nutrition programming still a challenge on both woredas.

Category 6: Lack of favorable institutional structure and capacity for nutrition program implementation: Strategies and plans can only be changed into meaningful impacts when sectors are clear on what institutional structures they set and their capacity to implement the plans. Sectors can assign a focal person, a unit, or a directorate, based on the level of the assignment, and continually builds the capacity for implementation.

National nutrition plan clearly indicated about the importance of adequate number and mix of competent nutrition cadres or technical persons at each sector at all level for effective and efficient NNP implementation.

The study findings from both woredas clearly showed the absence of proper structural arrangement for coordinating nutrition activities. Because there is no nutrition professionals among interviewed committee members including health sector. Apart from the absence of nutrition professionals; even woreda health office nutrition focal person has three duties and responsibilities. He is responsible to coordinate nutrition activities, child health services and expanded program of immunization activities and has a huge work burden. Due to the absence of proper structural arrangement for nutrition sensitive and nutrition specific interventions on both woredas, multisectoral nutrition activities still not coordinated properly. Therefore structural arrangement by itself is challenging for multisectoral nutrition coordination activities.

Category 7: Lack of community ownership: Community participant’s focus group discussion respondents stated that community resistance is one of the challenges for diversified feeding practice and proper child and women caring practices, even though health development armies and health extension workers are told them about good nutrition practice.

One participant said that "The community thought that health development armies will got per diem and incentives that is why they enforce us”, so this attitude should be improved by creating proper communication channel at community level added the respondent. Due to frequent fasting, feeding of animal source foods for young children also a challenge in fear of contaminating cooking and feeding materials said the respondents.

Theme 4: Opportunities of existing multi-sectoral coordination mechanisms

Despite of many challenges, the participants also identified current opportunities for effective coordination activities. Both woredas key informants stated that National nutrition program plan and organized NCB and NTC at each level can be a platform for effective coordination mechanism. In line with NNP structural arrangement, implementation guideline which consists of team composition, team responsibilities and communication mechanisms are outlined, given responsibility for higher officials (coordinating body) can also contribute for decision making and resource allocation. A number of development artners and non-government/civil society organizations are working with the government at all levels to improve the nutritional status of Ethiopians. NGOs involvement on financial and technical support also an opportunity since there are many NGOs working on nutrition interventions and contributing on capacity building training, IEC/BCC materials distribution and budget allocation. NNP objectives, milestones and indicators sensitization at each level was an entry point on the coordination of NNP activities, existed health development army structure can be the main contributor to reach pregnant and lactating women and young children specially for complementary feeding cooking demonstration, school structure can also be used as the main channel for information dissemination on proper nutrition practices through students to reach most of the population. In addition to system and structural opportunities surplus productivity of both districts, geographical accessibility to reach most of the kebeles and community can be considered as an opportunity said the participants.

Various examples of national and subnational multi-sectoral interventions for healthy growth illustrate how critical multisectoral approach reduces stunting. In Ethiopia, the revised NNP II has been designed to execute effective multi-sectoral nutrition coordination mechanism with revised institutional arrangement, along with the necessary authority, resources and accountability. The need for revision of NNP I was due to lack of budget, inadequate commitment and lack of strong, suitable governance structures for effective program implementation.

The study findings from both woredas reviled that their coordination mechanisms are similar from woreda to kebele level with nutrition coordination body and nutrition technical committee at woreda level and nutrition committee at kebele level.

Multi-sectoral plans, policies, and guidelines are key to ensuring that various sectors know what actions are expected of them to achieve their sectoral objectives. The level of awareness among interviewed informants of multi-sectors was variable on multi-sectoral nutrition coordination implementation up to community level. This was due to lack of regular updates of multi-sectoral representatives on their responsibilities. In addition implementation guidelines and TOR were not available on both woredas during document review even though it is critically important for effective coordination activities. Participant’s response has been varied during interview on differentiating TOR and joint planning documents and this shows that there is no clear vision and regular communication among multisectoral committee members.

In order to enhance accountability and maximize ownership, nutrition coordination body and nutrition technical committee need to regularly meet and discuss the progress of multi-sectoral nutrition coordination implementation. Moreover, all implementing sectors should regularly report on the progress of nutrition-sensitive and specific interventions and on the coordination and implementation to the nutrition coordination body and to their respective multisectoral nutrition interventions implementing sectors at each level.

Even though the terms of reference for nutrition coordination body and nutrition technical committee along with information on membership, frequency of meetings and the roles and responsibilities of multisectoral nutrition interventions implementing sectors detailed in a multisectoral nutrition coordination implementation guideline, the communication, monitoring and evaluation activities were not strategically coordinated due to poor coordination on both districts. Despite a lot of attention on the national nutrition program and sectoral decision makers are responsible for coordinating the resources and activities, nutrition technical committee key informants and kebele nutrition committee respondents cited lack of coordination as a key factor for in effective coordination and limiting the momentum for multisectoral nutrition coordination actvities. This problem is the same with findings of NNP I evaluation challenges which was absence of suitable governance.

Except the common understanding of structural coordination mechanisms, key informants of multisectors had different understanding on practical implementation status of coordination activities. Even joint planning, meeting and kebele nutrition implementation activities were not clearly communicated among multisector focal points. This may be due to poor coordination from national up to woreda level on regular update, communication and monitoring of the program.

On both woredas all kebeles were established nutrition committee but their roles and responsibilities had not clearly communicated and no technical support provided from both woredas. That is why poor multisectoral nutrition coordination at kebele level except nutrition specific routine activities by health sector. Planned nutrition sensitive activities of agriculture and education sectors are not implemented at community level due to non-functioning kebele nutrition committee.

While there is consensus on the goal of multisectoral nutrition coordination activities at district and kebele level, there is no clear understanding on coordination and collaboration. Especially most kebele nutrition committee members were unfamiliar with multisectoral nutrition coordination overall purpose and their role in the committee. It is critical that all woreda and kebele nutrition committee members should gain a clear understanding of coordination mechanisms, goals, and approach to collaboration. This will require specific awarenessraising efforts for committee members.

Accountability issue had been reported the other problem of multisectoral nutrition coordination mechanism. Participation in multisectoral nutrition coordination activities is not obligatory so it may be difficult to ensure accountability and recognition among those who participate. The health sector is the only responsible committee member who has nutrition specific work included in his/her job description. Other sectors focal persons consider coordination activities as secondary to their work, resulting in related efforts not being prioritized. Because it is not indicated in their work objectives or detailed in his/her organization order. That is why nutrition sensitive activities like poultry promotion and fruit and vegetables gardening at house hold and schools still not implemented properly.

If active participation by multisectoral nutrition coordination members is determined as crucial, it will be important that participating members are provided clear guidance regarding their roles and responsibilities, are recognized for their contributions, and accountable for their obligations.

Finally the respondents outlined the key challenges to be addressed for effective coordination activities like budget issue is a head ache for almost of their activities, poor coordination at each level, structural problems (nutrition interventions still have no independent nutrition professionals at woreda and facility level, rather integrated with other activities), lack of regular monitoring and evaluation, lack of common understanding and lack of accountability mechanisms. These challenges are almost the same as identified challenges during the study conducted on Multisector Nutrition Program governance and implementation in Ethiopia: Opportunities and challenges which were budget shortage, lack of attention, coordination problem, low awareness and lack of nutrition professionals [9,10].

From findings of both districts, multisectoral nutrition interventions are not effectively coordinated in both districts. Integrated programming and measuring program results is important not only to gauge effectiveness in regard to goal achievement but also to determine the level of impact on targeted beneficiaries.

Integrating M and E into program design is particularly beneficial for complex programs such as multisectoral nutrition programs because gaining access to data early allows managers to quickly discover inefficiencies, learn from them, and make changes to improve program implementation. Over the past years, the integrated supportive supervision, review meeting, regular report, feedback mechanisms and program evaluation were poorly coordinated at each level.

Lack of budget for coordination activities, lack of ownership at district level, absence of accountability mechanisms, absence of monitoring and evaluation activities, lack of effective communication and structural problems were the main challenges encountered during multisectoral nutrition coordination implementation on the study areas. Due to in effective coordination on the study areas, almost all challenges are still the same with the challenges identified during NNP I implementation.

Nutrition intervention activities at community level also not implemented as per the guideline. Especially nutrition sensitive programs are just left un-touched due to in effective kebele coordination activities. Health centers involvement was not clearly described on multisectoral nutrition coordination activities, especially on kebele committee support, that why community level nutrition sensitive and nutrition specific activities were poorly coordinated.

Appropriate feeding during pregnancy and lactation, optimal breast feeding, feeding appropriate complementary foods for young children are not still practical at community level. In summary 1000 days is not practically implemented at community level and needs regular program communication and advocacy.

Community level cooking demonstration for promoting appropriate complementary feeding practices has not been regularly conducted with community contribution and active involvement. The problem was not only the food items and community participation but also necessary food preparation materials were not available. There was no report tracking, monitoring and evaluation mechanisms on this activity and these gaps were related to poor coordination of NCB, NTC and kebele nutrition committee.

During the program implementation, established committee, program sensitization, health and education sectors community reach through their structure, NGOs involvement on nutrition projects and surplus productivity of both districts can be opportunities for effective functioning of multisectoral nutrition coordination in the study areas.

Ethiopian government designed national nutrition program II which can be accomplished with integrating multi stakeholders. Detailed initiatives like sekota declaration has been part of the national plan with zero stunting from our country by 2030. But unless inter and intra sectoral nutrition activities are properly coordinated and integrated malnutrition will remain as it is and that will be difficult to achieve the goal of stunting reduction.

• Current coordination activities seems secondary task of

multisectors Therefore, terms of reference should be prepared

to incorporate clear guidance for holding accountable for

coordination and collaboration activities of multisectors.

• Proper program communication, monitoring and evaluation

efforts should be underlined at each level for effective program

coordination.

• Institutional capacity should be improved: Nutrition

professionals should be assigned on woreda health office,

health facilities and even other sectors for independent

nutrition intervention activities: Currently in addition to the

absence of nutrition professionals, multiple duties like

nutrition, child health and immunization activities are given

for assigned nutrition focal person at woreda health office.

• The budget issue is still a bottleneck: No clear understanding

among multisectors about budget source for multisectoral

nutrition coordination activities and guidance should be

cascaded with clear accountability.

• Although community complementary food cooking

demonstration was indicated as an important activity, the

implementation is not being effectively coordinated. Therefore

implementation guideline with clear monitoring and

evaluation mechanisms should be cascaded.

• Strong collaboration with religious leaders is vital for tackling

the barriers for practical implementation of 1000 days

initiative.

• Concerned sectoral offices should be focus on practical

implementation of fruit and vegetables gardening at house

hold level and schools and poultry promotion activities.

• Incorporating health centers role on multisectoral nutrition

mechanisms can be better for kebele nutrition committee

support and functioning.

• Mid-term evaluation of the programs and correcting current

implementation gaps is needed for identifying gaps.

Ethical clearance has been obtained from Amhara public health institute to West Gojjam zonal health department and selected woredas as well. Permission letters also obtained from West Gojjam zonal health department and respective woredas. After providing clear and detail understanding about the aim of the study, oral consent has been obtained from each respondent before starting the interview. The confidentiality of all participants’ information has been secured.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Yimer S, Kasie TA (2023) Challenges and Opportunities for Coordinating Implementation of Multisectoral Nutrition Programs in West Gojjam Zone, North West Ethiopia. J Nutr Food Sci. 13:056.

Received: 27-May-2023, Manuscript No. JNFS-23-24475; Editor assigned: 30-May-2023, Pre QC No. JNFS-23-24475 (PQ); Reviewed: 13-Jun-2023, QC No. JNFS-23-24475; Revised: 26-Nov-2023, Manuscript No. JNFS-23-24475 (R); Published: 02-Dec-2023 , DOI: 10.35248/ 2155-9600.23.13.056

Copyright: © 2023 Yimer S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.