Advanced Techniques in Biology & Medicine

Open Access

ISSN: 2379-1764

ISSN: 2379-1764

Research Article - (2021)Volume 9, Issue 7

Background: Citrullinemia type 1 (CTLN1) is an autosomal recessive metabolic disease caused by ASS1 gene mutations encoding argininosuccinic acid synthase enzyme which is within the pathway of arginine and nitric oxide biosynthesis.

Methods: Disease confirmation was done by ASS1 gene mutation analysis using Next Generation Sequencing, DNA Sanger sequencing and bioinformatics. The study group members were17 citrullinemia type1 patients from 10 unrelated families referred to Iranian National Society for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism’s clinic between 2008-2020. Clinical, laboratory and molecular data were retrospectively evaluated.

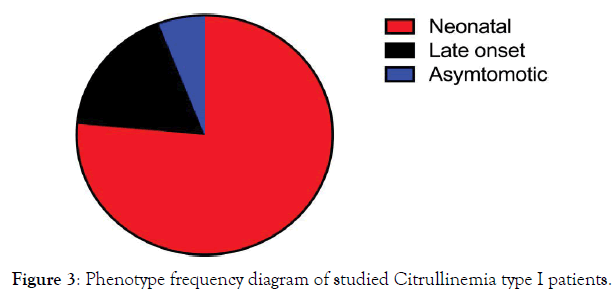

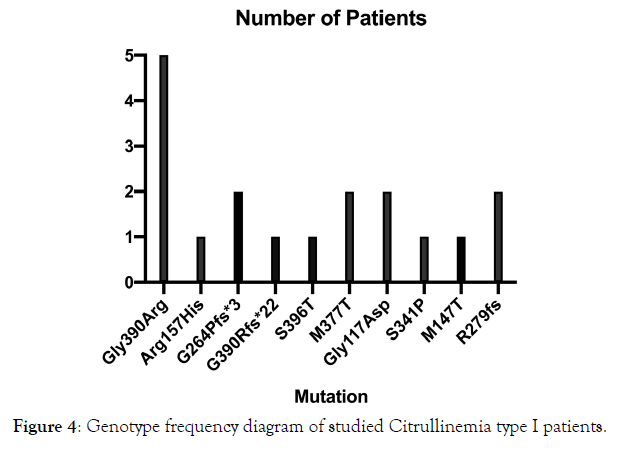

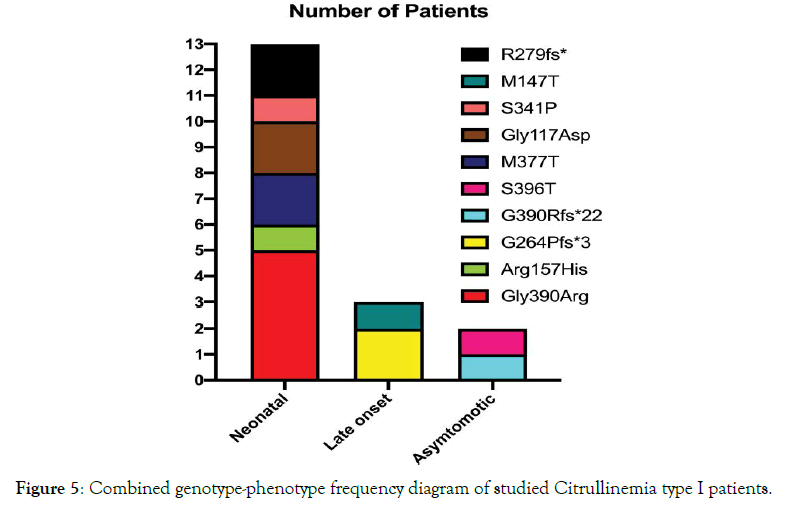

Results: Eleven different ASS1 gene mutations were detected. Presentation: 3/17 (76%) neonatal, 3/17 (18%) late infantile, 1/17(6%) asymptomatic. Severe developmental delay and intractable seizures despite metabolic control was the only surviver of neonatal form outcome. Two patients with late infantile form live metabolically and seizure controlled with quite normal performance. DNA mutations: 7 missense, 1 nonsense, and 2 indel mutations in twelve, two, three patients, respectively. Five novel mutations were detected including a homozygous GG deletion in exon 11 (c.790_791delGG; G264Pfs*3) and a homozygous mutation in exon 6 (c.440C>T; p.M147T), both leading to infantile form; a homozygous mutation in exon 14 (c.1130T>C; p.M377T) leading to neonatal form; two compound heterozygote mutations in exon 14 (c.1167_1168insC& c.1186T>A; p.S396T) leading to asymptomatic form. Five patients (38%) with classic neonatal form had mutation in exon14 of ASS1 (c.1168G>A; p.G390R).

Conclusions: Classic neonatal form was the most common form of disease in Iranian studied patients and exon 14: c.1168G>A; (p.G390R) was the most frequent ASS1 gene mutation. Global neonatal screening in Iran is recommended for citrullinemia type1 and certain mutations can be used for screening lethal form of disease in this population.

Citrullinemia type I(CTLN1); ASS1; Novel mutation; Clinical; Outcome; Iran

Citrullinemia type1 (CTLN1), or argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS) deficiency, is a rare autosomal recessive metabolic disorder caused by mutations in the ASS1gene [1]. It is a urea cycle disorder whose estimated incidence is 1 in 44,300-250,000, based on the literature on newborn screening using mass spectrometry [2-4]. CTLN1 shows heterogeneous clinical manifestations. The classic neonatal-onset form typically involves hyperammonemic encephalopathy with lethargy, failure to thrive, seizures, coma, and death early in life. Milder phenotypes (late onset) present with neurologic impairment, somnolence, and chronic intermittent hyperammonemia during infancy, childhood, and adulthood. Some individuals (biochemical phenotype) have an asymptomatic clinical course. To date, at least 137 mutations in ASS1, including gross deletions/duplications, have been associated with CTLN. Biochemically, ASS deficiency is characterized by hyperammonemia, hypercitrullinemia, and oroticaciduria [5].

The overall outcome of children with urea cycle defects remains poor even in the developed world where excellent infrastructure and facilities are available. Affected children are recognized when symptoms of hyperammonemia, such as lethargy and coma, occur even in screened neonates before test results are available. Delay in diagnosis can result in death or neurologic disability. This situation is exacerbated by a lack of awareness among families and primary physicians as well as inadequate facilities. Almost all of the CTLN1 patients in this study presented with somnolence, poor feeding, vomiting, coma, and seizures. An accurate genetic diagnosis can be helpful not only for better disease management but also for genetic counseling for subsequent pregnancies and carrier detection [6]. In Iran, comprehensive neonatal metabolic screening is not broadly available nor are Iranian ASS1 mutations reported. The Iranian population is a mix of several ethnicities with considerable consanguinity. Here, we present our experience in diagnosis, genetic testing, and outcomes after diagnosis of CTLN1. The data were collected from patients who were referred to the Iranian National Society for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism clinic.

Patients

Seventeen individuals withCTLN1 from 10 unrelated families entered the study. The patients, from around the country, were referred to the Iranian National Society for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism in Tehran, Iran between 2008 and 2020. Diagnosis was based on clinical symptoms and laboratory confirmation, i.e., elevated plasma citrulline levels determinedby MS/MS upon newborn screening or by HPLC (High Performance Liquid Chromatography) later, hyperammonemia determined by an enzymatic spectrophotometric assay (Randox Ammonium Kit, Randox Laboratories LTD, UK), and oroticaciduria determined by GC/MS(normally not detected). Standard treatment with ammonia scavengers, peritoneal dialysis, exchange transfusion (if dialysis was not available), L-arginine, L-carnitine, a low protein diet±special urea cycle defect formulas was carried out after diagnosis. Age of onset, clinical presentation, initial plasma citrulline and ammonia levels, clinical outcome, family history, and molecular genetic analysis were retrospectively evaluated.

Simulation of the Compression Hip Screw system (CHS)

The fixation device of CHS was provided by a commercial company. the CHS was created consistent with the sizes of device in SolidWorks, however, the simulated implant was simple comparing to the device, which the lag screw and compress screws were generated based on the plate without assembling the implant later, simultaneously, the screws were not sculptured by the springs for converging the complex smoothly. Finally, the generated implant was saved as the STEP file.

Molecular Genetic Analysis

Based on the suggestive clinical and biochemical parameters, the coding region and 5’-, 3’-UTRs of the ASS1 gene (ENST00000352480; NM_054012) were analyzed by Next Generation Sequencing (NGS). All detected variants in patients and their parents were validated utilizing Sanger sequencing at the diagnostic genetic laboratory of IUMS and TUMS hospitals. If the patient’s DNA was not available because of early death, only parent’s DNA was analyzed. Mutation analysis was done after parental consent was obtained. For families who planned for a healthy child, prenatal diagnosis was performed by amniocentesis at 13-14 weeks gestation. Mutation analysis was carried out in fetal DNA using Sanger sequencing to determine whether a fetus is affected with previously identified mutations. The primers and sequences are available upon request.

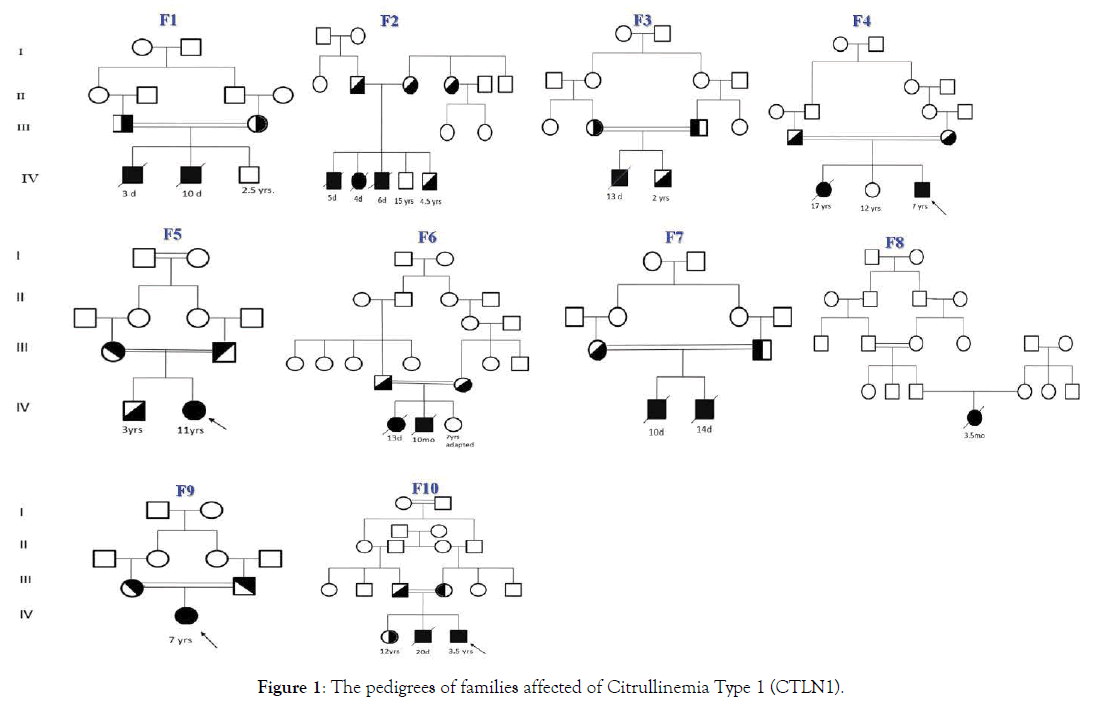

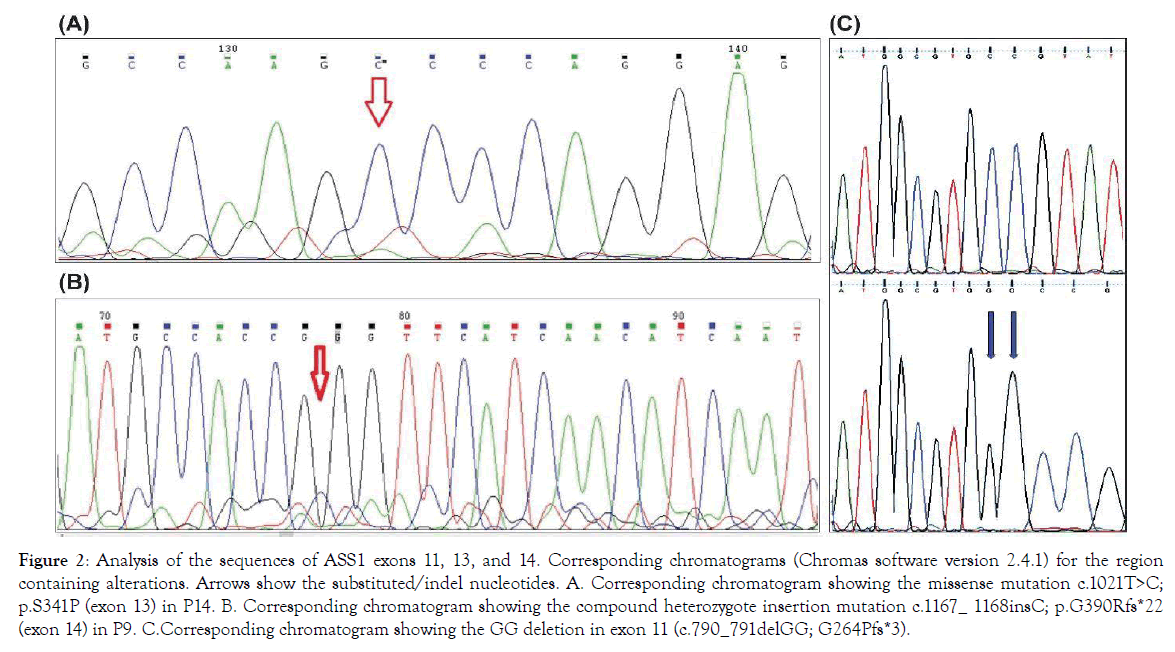

17 patients (7 female; 10 male) with CTLN1 from 10 unrelated families entered into this clinical genetics study based on their clinical and metabolic manifestations. Confirmation of disease was via molecular genetic analysis. Eight had consanguineous parents (Figure 1: Pedigrees of affected citrullinemia type 1 families). Ten different mutations (consisting of nine homozygous and one compound heterozygous mutation), including five novel variations, were detected in this cohort’s DNA (Table 1: Demographic, clinical, and genetic data of affected Citrullinemia type1 patients). They included 7 missense, 1 nonsense, and 2 indel mutations in twelve, two, and three patients, respectively. The missense mutations included: c.1168G>A; p.G390R (in P1-P5), c.470G>A; p.R157H (in P6), c.1186T>A; p.S396T (compound heterozygote in P9), c.1130T>C; p.M377T (in P10-P11), c.350G>A; p.G117D (in P12-P13), c.1021T>C; p.S341P (in P14), and c.440T>C; p.M147T (in P15). The only detected nonsense mutation was c.835C>T R279fs* (in P16-P17). The two indel mutations werec.790_791delGG; G264Pfs*3 (in P7-P8) and c.1167_1168insC; p.G390Rfs*22 (compound heterozygote in P9) (Table 2: Clinical, biochemical, and molecular data and outcomes of Citrullinemia type 1 patients). Chromatograms of the indel mutations and one of the missense mutations are shown in Figure 2 A-C. All of the above-mentioned variations were predicted to be deleterious mutations via testing by Mutation Taster (http:// www.mutationtaster.org/); five of the variations were previously reported as disease causing in CTLN1 patients.

Figure 1. The pedigrees of families affected of Citrullinemia Type 1 (CTLN1).

Figure 2. Analysis of the sequences of ASS1 exons 11, 13, and 14. Corresponding chromatograms (Chromas software version 2.4.1) for the region containing alterations. Arrows show the substituted/indel nucleotides. A. Corresponding chromatogram showing the missense mutation c.1021T>C; p.S341P (exon 13) in P14. B. Corresponding chromatogram showing the compound heterozygote insertion mutation c.1167_ 1168insC; p.G390Rfs*22 (exon 14) in P9. C.Corresponding chromatogram showing the GG deletion in exon 11 (c.790_791delGG; G264Pfs*3).

| Family | patient | Gender | Age at last follow up | Age of onset | First presentation | Parental consanguinity | Clinical presentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | P1 | Male | 3d | 3d | Poor feeding ,Somnolence | Yes | Neonatal |

| P2 | Male | 10d | 5d | Poor feeding ,Somnolence | Neonatal | ||

| F2 | P3 | Male | 5d | 3d | Poor feeding ,Somnolence | Neonatal | |

| P4 | Female | 4d | 2d | Poor feeding ,Somnolence | No | Neonatal | |

| P5 | Male | 6d | 2d | Poor feeding ,Somnolence | Neonatal | ||

| F3 | P6 | Male | 13d | 3d | Seizure, Coma | Yes | Neonatal |

| F4 | P7 | Female | 17yrs | 9mo | Seizure, Delay Development | Late onset | |

| P8 | Male | 7yrs | 8mo | Seizure, Delay Development | Yes | Late onset | |

| F5 | P9 | Female | 11yrs | 8yrs | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | |

| Yes | |||||||

| F6 | P10 | Female | 9d | 3d | Poor feeding, Coma | Neonatal | |

| P11 | Male | 10mo | 5d | Poor feeding, Coma | Yes | Neonatal | |

| F7 | P12 | Female | 10d | 3d | Poor feeding, Lethargy | Yes | Neonatal |

| P13 | Male | 14d | 4d | Poor feeding , Lethargy | Neonatal | ||

| F8 | P14 | Female | 3.5mo | 3d | Seizure, Somnolence | No | Neonatal |

| F9 | P15 | Female | 7yrs | 9mo | Vomiting, Somnolence | Yes | Late onset |

| F10 | P16 | Male | 20d | 3d | Poor feeding , Lethargy | Yes | Neonatal |

| P17 | Male | 3.5yrs | 3d | Poor feeding, Lethargy | Neonatal |

Table 1: Demographic, clinical, and genetic data of studied Citrullinemia type I patients.

| Family | patient | Initial plasma ammonia | Initial plasma citrulline | Paternal allele | Exon | Maternal allele | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| * | ** | (pro) | (pro) | ||||

| F1 | P1 | 1300 | 2500 | c.1168G>A p.G390A | 14 | c.1168G>A p.G390A | 5 |

| P2 | 1402 | 2600 | |||||

| F2 | P3 | 340 | 2046 | 14 | c.1168G>A p.G390A | 5 | |

| P4 | 540 | 2450 | c.1168G>A p.G390A | ||||

| P5 | 500 | 1489 | |||||

| F3 | P6 | NA | 777 | c.470G>A p.A157H | 7 | c.470G>A p.A157H | 1 |

| F4 | P7 | NA | NA | gg.deletion | 12 | gg.deletion | This study |

| P8 | 150 | 1400 | p.R403A | p.R403A | |||

| F5 | P9 | 109 | 1298 | c.1168inser p.G389A | 15 | c.1186T>A p.S395T | This study |

| F6 | P10 | 370 | 2927 | c.1130T>C p.M376T | 6 | c.1130T>C p.M376T | This study |

| P11 | 730 | 2469 | |||||

| F7 | P12 | NA | NA | c.350G>A p.G117A | 5 | c.350G>A p.G117A | 1 |

| P13 | 1476 | 758 | |||||

| F8 | P14 | 200 | 1536 | c.1022T>C p.S341P | 14 | c.1022T>C p.S341P | 1 |

| F9 | P15 | 298 | 1015 | c.440T>C p.M147T | 7 | c.440T>C p.M147T | This study |

| F10 | P16 | NA | NA | c.835C>T p.279R>X | 12 | c.835C>T p.279R>X | 7 |

| P17 | 1042 | 1154 |

Table 2: Demographic, clinical, and genetic data of studied Citrullinemia type I patients.

Of the five novel variations, two were found only in the asymptomatic patient (P9inF5) who was compound heterozygous for a variant in exon 14 of ASS1 (c.1167_1168insC & c.1186T>A; p.S396T). Two other novel mutations, found in the 3 late onset CTLN1 patients (P7, P8, P15)from two unrelated families, were located in exon 11 (c.790_791delGG; G264Pfs*3) and in exon 6 (c.440T>C; p.M147T) of the ASS1 gene. Also, one ASS1 novel variant in two classic neonatal CTLN1 patients (P10& P11) from one family (F6) was homozygous in exon 14 (c.1130T>C; p.M377T). Of the 10 studied families, seven presented during the neonatal period (70%) and two (29%) were homozygous for c.1168G>A; p.G390Rin exon 14 of ASS1. Prenatal diagnosis was performed for 3 families (F1, F2, F3) via amniocentesis at 13 weeks gestation. Fetal DNA extraction followed by Sanger sequencing and genetic analysis of previously identified mutations showed healthy heterozygous or homozygous fetuses. The newborns were followed up clinically and biochemically and did not show any abnormality.

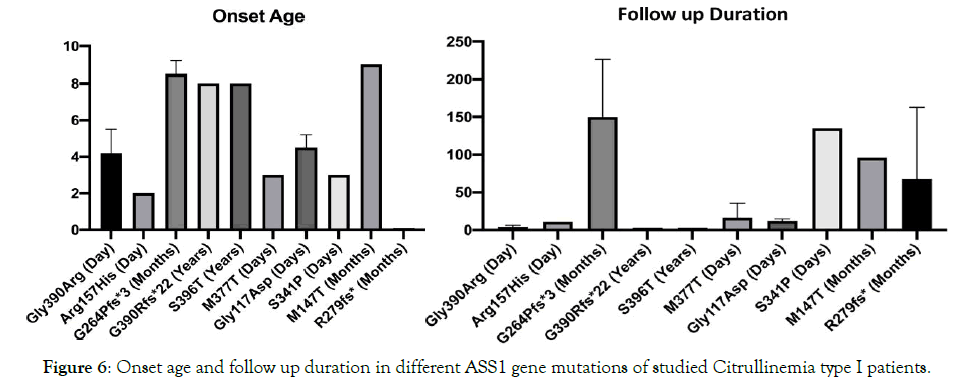

All patients were born to uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries, 16 of which were by elective cesarean section. The mean birth weight was 3,150 g (range, 2, 600-4, 250 g). Thirteen of 17patients (76%) had classic neonatal CTLN1 with a mean onset of 3.2 days (range: 2-5d) and mean ammonia and citrulline levels of 790 μg/dL (range: 200-1,402) and1, 820 μmol/L (range: 758-2,600), respectively. Ten of the 13(76%) died at a mean age of 9.8 days (range: 3-20d) despite proper treatment. The remaining 3 (P11, P14, P17) were discharged home at a mean age of 24 days (range: 11-38d). P11had normal growth and development with standard treatment until 10 months of age but succumbed during a severe hyperammonemic attack due to respiratory infection. P14lived until 3.5 months but had a severe delay in growth and development and frequent readmissions to the hospital for peritoneal dialysis. P17 was discharged at 11 days after two exchange transfusions and developed fairly well until 11 months when he had a severe seizure and began to regress. Currently at 4 years of age, he is unable to walk or speak and has refractory seizures despite metabolic control by standard treatment. Three patients (Table 3: 3/17; 17%; P7, P8, P15) were admitted with late onset CTLN1 at a mean age at onset of 8 months (range: 8-9 months). Their mean ammonia and citrulline levels were224μg/Dl (range: 150-298) and1, 207μmol/L (range: 1,015-1,400), respectively. P7 presented at age 8 months with vomiting and seizures but was undiagnosed until she died at 17 years of age, bedridden with refractory seizures because of late diagnosis. P8, her brother, is now an eight year old boy who presented with vomiting, seizures, and developmental delay at 9 months of age when standard treatment for CTLN1 was begun. He does fairly well at school but is hyperactive due to anticonvulsant therapy. He is currently metabolically controlled but has episodes of intermittent hyperammonemia. Enzyme assessment of this patient showed 50% enzymatic activity of argininosuccinate synthetase: 0.5 nmol/kg/mg prot (range:0.8-8). P15 presented at 9 months of age with lethargy, vomiting, and slight motor delay, at which point standard treatment was initiated. Currently, at 7 years of age, she is free of seizures and well-controlled mentally, physically, and metabolically and has good school performance. P9, the only asymptomatic patient, has been followed since she was 2.5 years old. She was brought to the clinic for poor weight gain but had no other signs or symptoms. High citrulline levels were revealed in the follow up for her constitutional growth delay. Lab tests were repeated yearly and she has remained developmentally normal without any clinical symptoms. However, standard therapy did not change her growth velocity or her biochemical abnormality, so treatment and protein restriction was discontinued at 11 years of age and she is now being followed up annually. She is currently symptom free yet still biochemically abnormal. Advice was given to the patient/family to follow her symptoms closely during pregnancies and major metabolic stresses. Figures 3 through 6 summarize the phenotype and genotype findings of the ASS1 gene in the studied Citrullinemia type I patients.

| Family no. |

Patient no. |

Consan guinity |

Gender | First Presentation | Onset age |

Follow up duration | Neuro development |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | P1 | positive | male | poor feeding | 3days | 4days | Delayed |

| P2 | male | poor feeding | 3days | 7days | Delayed | ||

| F2 | P3 | negative | male | poor feeding | 5days | 5days | Delayed |

| P4 | Female | poor feeding | 4days | 3days | Delayed | ||

| P5 | male | poor feeding | 6days | 2days | Delayed | ||

| F3 | P6 | positive | male | poor feeding | 2days | 11days | Delayed |

| F4 | P7 | positive | Female | Seizure | 9mo | 17 yrs | Delayed |

| P8 | male | Seizure | 8mo | 8 yrs | Delayed | ||

| F5 | P9 | positive | Female | short stature | 8yrs | 3yr | Normal |

| F6 | P10 | positive | Female | poor feeding | 3days | 6days | Delayed |

| P11 | male | poor feeding | 3days | 10mo | Normal | ||

| F7 | P12 | positive | Female | poor feeding | 5days | 10days | Delayed |

| P13 | male | poor feeding | 4days | 14days | Delayed | ||

| F8 | P14 | negative | Female | poor feeding | 3days | 3.5mo | Delayed |

| F9 | P15 | positive | Female | vomiting | 9mo | 8yrs | Delayed |

| F10 | P16 | positive | male | poor feeding | 3days | 20days | Delayed |

| P17 | male | poor feeding | 3days | 3.5yrs | Delayed |

Table 3: Clinical, biochemical, and molecular data and outcomes of studied Citrullinemia type I patients.

Figure 3. Phenotype frequency diagram of studied Citrullinemia type I patients.

Figure 4. Genotype frequency diagram of studied Citrullinemia type I patients.

Figure 5. Combined genotype-phenotype frequency diagram of studied Citrullinemia type I patients.

Figure 6. Onset age and follow up duration in different ASS1 gene mutations of studied Citrullinemia type I patients.

Argininosuccinate synthetize is a rate limiting enzyme in the urea cycle coded by the ASS1 gene located on chromosome 9q34.1 which contains 16 exons [7]. Prenatal diagnosis of at risk pregnancies require prior identification of the disease causing mutation within the family [8].

There are two main reasons for prenatal diagnosis of urea cycle disorders: 1) to enable parents to terminate affected pregnancies or 2) to allow precautions to be taken immediately after birth [9].

In this study, we describe seventeen patients who were/are affected with CTLN1, including thirteen neonatal, three late on set, and one asymptomatic patient. This study was similar to two previous studies on Indian and KoreanCTLN1 patients in terms of showing a high prevalence of neonatal presentation [10]. Eleven different ASS1 variations, including five novel and six previously reported mutations [11], were ascertained in our patients. Although biochemical and enzymatic studies using tissue and fibroblasts are important for the diagnosis of CTLN1 [12], the molecular genetic investigation of theASS1 gene can help establish a genotypephenotype correlation, understand phenotypic variability, and comment on prognosis [6-9]. The enzymatic activity of fibroblasts may be normal in children with citrullinemia or, conversely, have no enzymatic activity in asymptomatic patients; thus, sequencing of the ASS1 gene is recommended to confirm diagnosis and predict the prognosis of citrullinemia patients [13-15]. It also allows prenatal diagnosis for future pregnancies and carrier detection within affected families for genetic counseling [16].

In this study, the majority of variations occurred in exon 14 (47%) in 4 out of the 10 independent families (40%). This was followed by variations in exons 11 and 6 as the second and third most frequent mutations, respectively. Exons 14, 11, and 6 of the ASS1 gene are suggested to be hot spots for tier 1 screening of patients with CTLN1 in Iran. This is compatible with other studies showing that most mutations of the ASS1 gene are distributed throughout the gene, except for exons5 and 12-14 [17]. The majority of patients in our study (>94%) were homozygous for ASS1 gene mutations; only one patient (P9)with compound heterozygote mutations (c.1167_1168inserC &c.1186T>A) was clinically asymptomatic but biochemically affected. Interestingly, this asymptomatic case (P9 inF5), which also showed compound heterozygosis for variants in exon 14 of the ASS1gene, is also the product of consanguinity. This pattern was compatible with previous studies in which mild/ asymptomatic phenotypes were compound heterozygous and probably had residual enzyme activity [6-9]. In another study, a woman with ASS1 compound heterozygous mutations who had a mild phenotype presented with severe symptoms during pregnancy and postpartum [6-10]. Most of our patients showed missense homozygote mutations of the ASS1 gene with more than 94% of them being affected by a severe neonatal form of CTLN1. Therefore, in this study, similar to previous studies [2,15], missense mutations were mostly accompanied by early onset lethal clinical courses. On the other hand, (Table 4). we had two patients with missense mutations of the ASS1 gene that responded to treatment developmentally (P11 (early onset) and P15 (late onset)). Gao et al. showed that the phenotypes of certain missense mutations are mostly late onset/mild [7]. The majority of described ASS1 mutations are missense mutations; however, patients show highly variable clinical courses [17]. It can be concluded from the literature [1,6,9] and this study that a reliable prognostic factor for the course of the disease is still to be found and that genotype-phenotype correlation is not very strong. Future studies with genotyping, phenotyping, and enzyme measurement is recommended to find a correlation. However, our study on 17 Iranian CTLN1 patients suggests that heterozygous missense ASS1 mutations, but not homozygous missense ones, have a mild/asymptomatic course of the disease.

| Family no. |

Patient no. |

Seizure | Hyper ammonemic Attacks |

Mean Glutamine | Mean Citrulline |

Liver enzyme | Urine orotic acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | P1 | yes | 1 | N/A | N/A | elevated | positive |

| P2 | yes | 1 | 1500 | 4230 | elevated | positive | |

| F2 | P3 | No | 1 | 1200 | 1489 | elevated | positive |

| P4 | No | 1 | 1500 | 2450 | elevated | positive | |

| P5 | No | 1 | 1800 | 2046 | elevated | positive | |

| F3 | P6 | yes | 1 | 1400 | 800 | elevated | positive |

| F4 | P7 | yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | Normal | N/A |

| P8 | yes | 4 | 700 | 1147 | Normal | positive | |

| F5 | P9 | No | 0 | 880 | 1298 | Normal | positive |

| F6 | P10 | yes | 1 | 1700 | 2927 | elevated | positive |

| P11 | No | 3 | 1780 | 2409 | elevated | positive | |

| F7 | P12 | No | 1 | N/A | 1000 | elevated | Negative |

| P13 | No | 1 | N/A | 758 | elevated | Negative | |

| F8 | P14 | yes | 5 | 850 | 3300 | Normal | positive |

| F9 | P15 | No | 3 | 1100 | 2717 | elevated | positive |

| F10 | P16 | yes | 1 | 1000 | 1680 | elevated | positive |

| P17 | yes | 6 | 1042 | 1550 | Normal | positive |

Table 4: Clinical, biochemical, and molecular data and outcomes of studied Citrullinemia type I patients.

A paucity of data on genotype-phenotype correlations and the various genotype combinations also cause confusion in the prediction of the clinical course of the disease according to genotype [1,6,7,15]. Many (38.5%) of our neonatal classic CTLN1 patients (P1-P5) were homozygous for a common mutation of ASS1 (c.1168G>A; p.Gly390Arg), which caused the most fulminant disease course, leading to liver failure and early neonatal death despite treatment. This is consistent with the literature [1-3, 5-16]. Only one of our classic neonatal CTLN1 patients (P17) is currently alive. He is a 3 year old boy who cannot walk independently and has intractable seizures and speech delay despite ammonia control. This confirms the poor prognosis of the classic neonatal form of CTLN1 as expressed in previous studies [2, 3,12,15].

Mean initial citrulline levels were 1820, 1207, and 1298 μmol/L in our neonatal, late onset, and asymptomatic CTLN1 patients, respectively (range: 758-2927) (Table 1). The initial citrulline concentrations were less than 1,000μmol/L in some of the severe neonatal patients and more than 1,000 μmol/L in the late onset and asymptomatic CTLN1 patients in our study group. However, it is still unclear whether the level of citrulline alone enables classification of patients [6,9,11,15]. During follow up, the late onset and asymptomatic CTLN1 patients showed lower ammonia levels during metabolic decompensation compared to neonatal classic patients (<100μg/L vs.>200μg/L). Although the mean citrulline levels were high (>1000 μmol/L) in all patients who had attacks of metabolic decompensation, the late onset and asymptomatic CTLN1 patients in our study group had better outcomes than the neonatal classic patients. This may reflect the fact that isolated episodes of hyperammonemia are not as deleterious as cumulative exposure to moderately high levels of ammonia or citrulline [18].

The activity of argininosuccinate synthase is likely a useful and essential tool in predicting long- term outcomes and for interpreting functional effects of sequence variants. A better understanding of each mutation’s effect would enable prediction of metabolic decompensation and lead to better management to prevent neurologic sequel [19,20].

Finally, the conclusion was that the stability evaluated by the displacement and the fracture risk evaluated by the von finally, prenatal diagnosis (PND) was done successfully in 3 of our 10 affected families, and no germ line (de novo) mutation was observed Table 5. PND is recommended for Iranian families affected withCTLN1because our study shows that the majority of mutations do not respond well to treatment even if started early in the disease course.

| Family no. |

Patient no. |

Renal Stones /involvement | Locus | Mutated nucleotide |

Mutated protein |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | P1 | No | Exon15 | 1168G>A | Gly390Arg | Deceased at neonatal period without Treatment |

| P2 | No | Exon15 | 1168G>A | Gly390Arg | Deceased at neonatal period despite Treatment |

|

| F2 | P3 | No | Exon15 | 1168G>A | Gly390Arg | Deceased at neonatal period despite Treatment |

| P4 | No | Exon15 | 1168G>A | Gly390Arg | Deceased at neonatal period despite Treatment |

|

| P5 | No | Exon15 | 1168G>A | Gly390Arg | Deceased at neonatal period despite Treatment |

|

| F3 | P6 | yes | Exon7 | 470G>A | Arg157His | Deceased at neonatal period despite Treatment |

| F4 | P7 | No | Exon12 | 790-791delGG | G264Pfs*3 | deceased severely retarded with intractable seizure without treatment |

| P8 | No | Exon12 | 790-791delGG | G264Pfs*3 | seizure controlled with treatment but mild impaired school performance |

|

| F5 | P9 | No | Exon14 | 1167-1168 insC & 1168T>A |

G390Rfs*22 & S396T |

only biochemically abnormal |

| F6 | P10 | No | Exon14 | 1130T>C | M377T | Deceased at neonatal period without Treatment |

| P11 | No | Exon14 | 1130T>C | M377T | Good growth and development after treatment but deceased by attack of high ammonia |

|

| F7 | P12 | No | Exon5 | 350G>A | Gly117Asp | Deceased at neonatal period without Treatment |

| P13 | No | Exon5 | 350G>A | Gly117Asp | Deceased at neonatal period despite Treatment |

|

| F8 | P14 | No | Exon14 | 1021T>C | S341P | Severely delayed growth and development despite treatment, deceased after repeated admissions |

| F9 | P15 | yes | Exon7 | 440C>T | M147T | Good growth and development after treatment and good school performance |

| F10 | P16 | No | Exon12 | 835C>T | R279fs* | Deceased at neonatal period without Treatment |

| P17 | No | Exon12 | 835C>T | R279fs* | Delayed developmentally and intractable seizure despite treatment and metabolic control |

Table 5: Clinical, biochemical, and molecular data and outcomes of studied Citrullinemia type I patients.

Classic neonatal CTLN1 was the most common form of CTLN1 in an Iranian population and c.1168G>A was the most common ASS1 mutation. In view of the poor prognosis of treated patients, prenatal diagnosis in neonatal CTLN1 families can prevent disease in subsequent pregnancies. Detection of genetic carriers in families affected by CTLN1 would be a useful means of diagnosis to prevent lethal forms and to better manage the more curable forms at birth. Global neonatal screening in Iran is recommended for CTNL1 because the majority of cases are the severe neonatal form of the disease in this population and specific gene mutation detection panels for lethal forms can be used for this issue.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the families for their assistance in this research even when their children were so ill. This study was supported by a research grant from Tehran University of Medical Sciences. We would also like to thank Dr. Janet Webster for critically reading and editing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

All patient subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. (Project identification code: IR.TUMS.REC.1395.2327).

Citation: Citation: Moarefian S, Zamani M, Rahmanifar A, Behnam B, Zaman T (2021) Clinical, Laboratory Data and Outcomes of 17 Iranian Citrullinemia Type 1 Patients: Identification of Five Novel ASS1 Gene Mutations. Adv Tech Biol Med. 9:308. doi: 10.35248/2379- 1764.21.9.308.

Received: 11-Jun-2021 Accepted: 30-Jun-2021 Published: 07-Jul-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2379-1764.21.9.308

Copyright: © 2021 Moarefian S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.