Pancreatic Disorders & Therapy

Open Access

ISSN: 2165-7092

ISSN: 2165-7092

Research Article - (2020)Volume 10, Issue 2

Purpose: Even though endoscopic necrosectomy for walled-off pancreatic necrosis is safe and effective, open surgery

has an important role in cases with extended necrosis when the non-surgical approaches are not feasible. Authors

compare their results of conventional and transgastric open necrosectomy.

Methods: A total of 29 patients were treated with extended walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Conventional open

necrosectomy with closed bursal lavage was performed in group A (18 patients) and transgastric necrosectomy was

performed in group B (11 patients). There were no significant differences between the two groups related to sex, age,

etiology of pancreatitis, size of WOPN and time elapsed from the onset of disease and surgery.

Results: For all complications, the difference was significant between both groups (p=0.003). In group A, 13

reoperations were performed in 9 patients and none were required in group B. The difference between both groups

was significant (p=0.01). The length of hospital stay was 23 ± 14.16 days in group A and 12 ± 2.2 days in group B. The

difference was significant (p=0.001). The mortality in group A was higher than in group B (p=0.143), but it was not

significant. The mean mortality rate was 13.8% in 29 patients.

Conclusion: In patients with extended walled-off pancreatic necrosis, the open transgastric necrosectomy has better

results than conventional necrosectomy.

Walled-off pancreatic necrosis; Open surgery

WOPN: Walled-off Pancreatic Necrosis; LOS: Length of Hospital Stay

Although many authors present excellent results of endoscopically treated patients with walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN), surgical treatment also has an important role in the treatment. While endoscopic transgastric necrosectomy (TN) is safe and effective [1-16], this approach is generally not effective enough in cases of extended necrosis. Although surgical treatment is also effective, it has a higher rate of complications and does not have the advantages of minimally invasive surgery. Patients with extended WOPN require open surgical necrosectomy since the location and gross of the necrotic mass are not suited for other non-surgical interventions [2,6,7,11-14,17-30].

Due to classic prandial habits – fatty food with strong alcoholic drinks – most of the WOPNs are extended and not available for endoscopic or minimal invasive approaches.

The aim of this paper is to compare results of conventional open necrosectomy with closed bursa omental lavage and open transgastric necrosectomy for extended, retrocolic WOPN.

In all cases of severe acute pancreatitis step-up treatment (conservative and semiconservative therapy) was used as basic therapy. Beside naso-jejunal feeding the developed SIRS was treated by intensive therapeutics. Routine antibiotic prophylaxis was not used, but in case of bacterial superinfection antibiotics (e.g. Imipenem or Fluorochinolones) were started than they were changed if needed on the results of bacterial stains. In cases of sterile or infected peripancreatic fluid collections that did not showed spontaneous resolving tendency and/or necrosis percutaneous drainage was indicated. Through the drain(s) lavage was performed if the drainage was not effective alone. Surgery was indicated only in selected cases if conservative or semiconservative therapy were unsuccessful. The ideal surgical indication was WOPN that were not suited for endoscopic or radiologic interventions because of the gross and location of the necrotic mass. In a 5-year period 29 patients with symptomatic extended WOPN were operated on. Only those patients with WOPN that failed conservative or semiconservative treatment were analysed in this study.

The 29 patients were divided into two groups based on the type of the surgical technique. Patients in group A (18 patients) underwent conventional necrosectomy and those in group B (11 patients) received transgastric necrosectomy. The demographic data of the two groups were compared and statistical analysis was performed (Table 1).

| Group A (18) | Group B (11) | Total (29) | p<0.05 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 9 Male 9 Female |

7 Male 4 Female |

16 Male 13 Female |

p=0.702 ’NS’ Chi-Squared Test |

| Age (year) | 59.4 ± 14.34 | 60 ± 15.59 | 59.9 ± 14.56 | p=0.835 ’NS’ Two-sample t-test |

| Etiology | 14 Alcohol abuse & fatty diet 2 Biliary origin 2 Hyperlipidemic |

6 Alcohol abuse & fatty diet 5 Biliary origin 0 Hyperlipidemic |

20 Alcohol abuse & fatty diet 7 Biliary origin 2 Hyperlipidemic |

p=0.068 ’NS’ Chi-Squared Test |

| Elapsed time (day) | 73.8 ± 62.54 | 81 ± 65.07 | 76 ± 62.45 | p=0.368 ’NS’ Mann-Whitney Test |

| Size of WOPN (cm) | 13.16 ± 4.69 | 12 ± 4.26 | 12 ± 4.49 | p=0.507 ’NS’ Two-sample t-test |

Table 1: Demography of patients, NS: Not significant difference, WOPN: Walled-off pancreatic necrosis.

There were 16 males and 13 females. The male/female ratio was 9/9 in group A and 7/4 in group B. The mean age of all patients was 59.9 ± 14.56. It was 59.4 ± 14.34 and 60 ± 15.59 years in groups A and B respectively.

| Group A | Group B | Total | p<0.05 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOS (day) | 23 ± 14.16 | 12 ± 2.2 | 19 ± 13.02 | p=0.001 ’S’ T-test |

| Complication | 5 Pseudocyst 4 Subsequent septic focus 3 Bleeding 1 Peritonitis |

1 Stenosis of cysto-gastrostomy | 5 Pseudocyst 4 Subsequent septic focus 3 Bleeding 1 Peritonitis 1 Stenosis of the cysto-gastrostomy |

p=0.003 ’S’ Chi-Squared Test |

| Reoperation | 13 | 0 | 13 | p=0.01’S’ Chi-Squared Test |

| Mortality | 4 | 0 | 4 | p=0.143 ’NS’ Chi-Squared Test |

Table 2: The results of the two different surgical therapy, LOS: Length of Hospital Stay, NS: Not significant difference, S: significant difference.

The most common etiology was fatty diet with alcohol abuse in 20 cases. There was a biliary etiology in 7 cases and hyperlipidemia in two cases could be verified as the cause of pancreatitis. In group A, 14 patients had a high-fat diet with alcohol abuse, 2 patients with biliary origin and 2 patients with hyperlipidemia were observed. In group B, 6 had fatty diet with alcohol abuse and 5 with biliary pancreatitis were the possible cause of the disease.

The mean time between surgery and the onset of the disease was 76 ± 62.45 days. This was 73.8 ± 62.54 and 81 ± 65.07 days in groups A and B respectively.

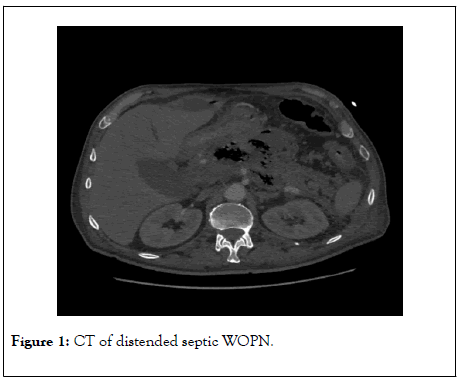

The mean diameter of retrogastric part of the WOPN was 13.15 ± 4.69 cm in group A and 12 ± 4.26 cm in group B. In addition to retrogastric localization of WOPN retrocolic extension was also observed in all patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1: CT of distended septic WOPN.

As it is seen in Table 1, there was no significant difference between both groups in relation to age, gender, etiology, size of WOPN and the interval between the onset of the pancreatitis and the operation using chi-squared and two-sample t-test with a p value less than 0.05.

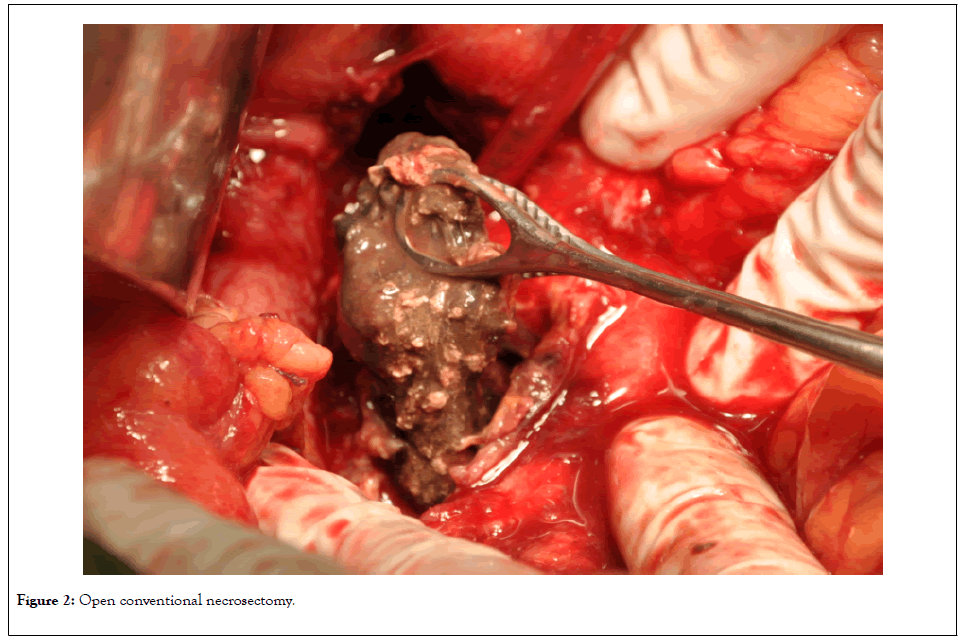

Of the 29 patients, 18 (group A) were operated with conventional open necrosectomy through the gastrocolic ligament using blunt and water-jet techniques (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Open conventional necrosectomy.

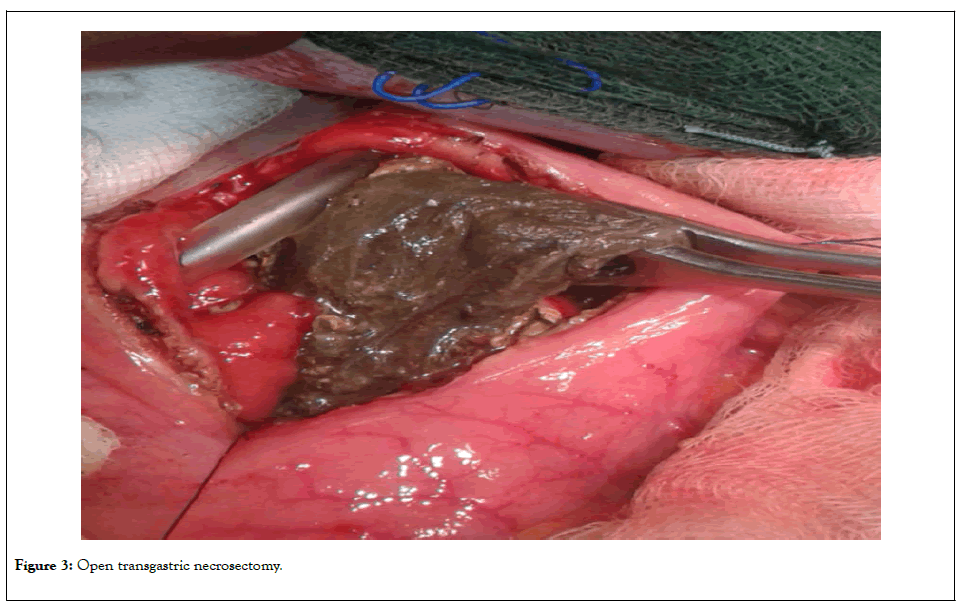

In these patients, postoperative closed omental bursa drainage was performed. The 11 patients (Group B) with evidence of retrogastric localization of the WOPN were operated transgastrically (Juras operation) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Open transgastric necrosectomy.

The necrosectomy was performed bluntly with water-jet technique. In these patients, a nasogastric tube was inserted into the cavity site after necrosectomy. The retroperitoneal spaces were also necrosectomized in all cases.

The groups were compared in relation to complication rates and reoperations, postoperative length of hospital stay (LOS) and mortality.

There were no intraoperative complications except one in group A; during blunt necrosectomy, a duodenal perforation was observed on the second postoperative day. This did not need reoperation and it closed spontaneously after 10 days.

Endoscopic lavage and necrosectomy were required after transgastric necrosectomy two times in one patient.

Early and late postoperative complications (bleeding, subsequent septic focus, peritonitis, bowel perforation-necrosis, metabolic acidosis and pseudocyst) occurred in 9 patients (47.4%) in group A and in one patient (9.1%) (stenosis of the cystogastrostomy) in group B. Total complications were analyzed using a nonparametric chi-squared test (p<0.05) and the difference was significant (p=0.003) between both groups.

Reoperation was performed 13 times in 9 patients in group B, but none were necessary in group A. The difference between groups A and B was significant (p=0.01) (non-parametric chisquared test, p<0.05).

In group B, there was no mortality. Using chi-squared test, the mortality in group A was not significantly higher than in group B with a p value of 0.143. The mean mortality of all 29 patients was 13.8%.

There were no late complications, such as pseudocyst formation, in group B. However, 5 patients in group A needed later reoperation due to a large pseudocyst.

Mean length of hospital stay (LOS) after necrosectomy was 19 ± 13.02 days. LOS was 23 ± 14.16 days in group A and 12 ± 2.2 days in group B. The difference between the two groups was significant (p=0.001), which was determined by using a twosample t-test (p=0.05).

On the basis of the revised Atlanta Classification, walled-off pancreatic necrosis is a well-defined entity as a local complication in severe acute pancreatitis. Then this entity develops, it is generally accepted that surgical or endoscopic intervention should be performed at this time for. This is a minimum of 4-6 weeks, but the optimal time is more than 6-8 weeks from the onset of the diseases [1,3,4,6-8,11-14,16 18,23,26,27,29,30].

There are many options for the treatment of WOPN. Progressively more publications are presented about endoscopic approaches. During this procedure, the necrotic tissue with pus can be removed with different transgastric or transduodenal endscopic maneuvers or with external precutaneous drainage. Some authors suggest performing necrosectomythrough self-expandable stents [1-16].

Although transluminal endoscopic necrosectomy is safe and effective, there are some limits to this approach. For extremely thick walls ( ≥ 10 mm), endoscopic treatment is not possible [8,10 12,14]. Other limits of this treatment include cases where the WOPN is not accessible with the gastroduodenoscope and the amount of necrotic tissue is too large [1,11].

There are many types of surgical procedures for the treatment of WOPN. Some are minimally invasive such as the laparoscopic or retroperitoneoscopic modalities. Minimally invasive proced ures also have limits based on the location and extension of necr osis [6,7,9,11-14,16,18,24,27].

The most common surgical interventions for WOPN is open necrosectomy through laparotomy. The open necrosectomy (thro ugh the gastrocolic ligament or the mesocolon) can be completed with open packing of the omental bursa with planned reoperatios or with postoperative closed lavage [6,7,11-14,17,19-23,31]. The necrosectomy can also be performed transgastrically via laparotomy or laparoscopically [12-14,24,22-27,29,30].

Surgical Transgastric necrosectomy is indicated mostly when the WOPN is large, has connection to the stomach, has also retrocolic extension and if minimal invasive surgery is impossible (adhesions, previous operations, etc.) or the endoscopic approach failed. Cholecystectomy can also perform simultaneously with TN.

The advantage of transgastric operations is that pancreas fistula and pseudocyst formation is impossible after this procedure because of the anastomosis formation between the stomach and the WOPN. After these operations, a second surgery is rare in contrast to the conventional open necrosectomy with closed bursal sac irrigation and drainage. As in 5 of the 18 patients pseu docyst can develop after conventional open necrosectomy and necessitate the need for one more operation or other interventions. After transgastric necrosectomy, there was no need for reoperation due to pseudocyst formation in the presented series [16-20,22,24-27,29,30].

TN for WOPN has an acceptable rate of morbidity and mortality with good results.

On the basis of their experience, the authors suggest the transgastric necrosectomy if it is possible. After the transgastric approach, the possible pancreatic fistula and pseudocyst formation are cured at the same time with the necrosectomy.

Open and transgastric necrosectomy are safe and effective. The open surgery is indicated in cases with large WOPNs with retrocolic extension. On the basis of better early and late results, the transgastric approach is suggested. On the other hand, this procedure is prophylactic in nature as it prevents pancreas fistulas or pseudocyst formation.

The limits of this study is first the relative small number of patients, second this study is a retrospective comparison.

Citation: Szentkereszty Zs, Krasnyánszky N, Kammili A, Balog K, Berhés M, Sápy P Gy (2020) Comparative Study of Conventional and Transgastric Necrosectomy for Wide Extended Walled-of Pancreatic Necrosis. Pancreat Disord Ther 9:199. DOI: 10.4172/2165-7092.20.10.1000199

Received: 18-May-2020 Accepted: 08-Jun-2020 Published: 16-Jun-2020 , DOI: 10.35248/2165-7092.20.10.199

Copyright: © 2020 Szentkereszty Zs, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.