Journal of Clinical & Experimental Dermatology Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-9554

+44 1478 350008

ISSN: 2155-9554

+44 1478 350008

Research Article - (2021)

Background: For more than half a century, cosmetic dermatology has been an integral part of dermatology practice. Dermatologists perform more cosmetic procedures than any other specialty on the basis of data from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Therefore; it is essential that young dermatologists be educated about cosmetic procedures and achieve competency and proficiency in this area, to provide competent care.

Aim of the study: This study aimed to assess the current state of cosmetic dermatology training in residency programs.

Objectives: To assess the educational exposure of dermatology residents to cosmetic dermatology, to elicit their perceptions on the effect of various teaching strategies for developing procedural skills during their residency in SCFHS-accredited programs in Saudi Arabia, focusing on the residents experience and perspective.

Methods: An analytic cross-sectional study was performed on Saudi Dermatology residents in Saudi Arabia at 2019. Permission was taken from Champlain et al. to use the questionnaire. An anonymous self-administrated questionnaire was used which included two parts: the first part inquired about demographic information and the second part inquired about cosmetic dermatology training during residency. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 20.

Results: Thirty six dermatology residents participated in this study with mean age (27.6 ± 1.9), 61.1% were female, 33.3% were in the 4th year and 22.2% were in the first year. Nearly 55.5% of the participants, their residency program were with more than 15 residents. 86% of them had formal lectures including laser, filler, sclerotherapy and chemical peels while 63% were only observer during different cosmetic procedures. Residents in the cosmetic dermatology program prefer more hands-on training (61%) versus lectures (25%) or assigned readings (11%).

Conclusion: The residency training program in Saudi Arabia like many programs that provide hands-on cosmetic dermatologic training but there is still lack in the level of participation as a primary surgeon which needs more facilities in both devices and procedures.

Dermatology; Cosmetic; Residents; Sclerotherapy; Survey

For more than half a century, cosmetic dermatology has been an integral part of dermatology practice [1]. Dermatologists perform more cosmetic procedures than any other specialty on the basis of data from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services [2]. The last several years have seen a dramatic increase in the number of patients seeking cosmetic procedures performed by dermatologists.

Based on data from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, more than 8 million cosmetic treatments were performed by dermatologists in 2017, an increase of 19% compared to 2016 results [3]. As the emphasis on cosmetic procedures in dermatology continues to grow, training in dermatology must reflect these trends. Therefore; it is essential that young dermatologists be educated about cosmetic procedures and achieve competency and proficiency in this area, to provide competent care.

Our study aimed to assess the current state of cosmetic dermatology training in residency programs. We present the results of this survey to provide a comprehensive overview of cosmetic dermatology training during residency in SCFHS-accredited programs in Saudi Arabia, focusing on the resident experience and perspective.

This cross-sectional study was conducted among Saudi Dermatology residents in Saudi Arabia at 2019. Permission was taken from Champlain et al. [4] to use the questionnaire. An anonymous self-administrated questionnaire was used and distributed as an electronic form using Google forms and consisted of two parts: the first part inquired about demographic information and the second part inquired about cosmetic dermatology training during residency, including educational approaches at their program, exposure to didactic and hands-on cosmetic training, resident proficiency with cosmetic procedures, perceptions of various teaching methods’ efficacy in fostering procedural proficiency, and future career plans.

This study was approved by biomedical ethical committee at King Abdulaziz University (Ref). All participants were notified about the study objectives and response confidentiality, and we took their consent. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before they proceeded to response.

Data management

Data were analyzed using the SPSS software version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Non parametric parameters were reported as frequency and percentage (%) and parametric parameters as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) and minimum and maximum.

A total of thirty six residents participated in the survey, Table 1 shows participants characteristics.

| Characterstics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | 27.6 ± 1.9 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 14 (38.8) |

| Female | 22 (61.1) |

| Year of residency | |

| PGY-1 | 8 (22.2) |

| PGY-2 | 5 (13.8) |

| PGY-3 | 9 (25) |

| PGY-4 | 12 (33.3) |

| Recent graduate | 2 (5.5) |

| Residency program size | |

| 1-5 Residents | 3 (8.3) |

| 5-10 Residents | 4 (11.1) |

| 10-15 Residents | 9 (25) |

| >15 | 20 (55.5) |

| Residency program region | |

| Central region | 9 (25) |

| Eastern region | 8 (22.2) |

| Western region | 12 (33.3) |

| South region | 7 (19.4) |

| Future career plan | |

| Academics | 13 (36.1) |

| Private practice | 10 (27.7) |

| Fellowship-cosmetic dermatology | 9 (25) |

| Fellowship-procedural dermatology | 5 (13.8) |

| Fellowship-pediatric dermatology, dermatopathology or advanced medical dermatology | 11 (30.5) |

| Not sure | 11 (30.5) |

Table 1: Summary of participants characteristics.

Most residents (80.5%) receive formal lectures at off-site conferences, affiliated private practice physicians (19.4%), and by core faculty lectures (16.6%). Online references and electives were other reported formats. The most commonly presented subjects include lasers (75%), fillers (50%), neurotoxins (47%), chemical peels (25%) and sclerotherapy (11%).

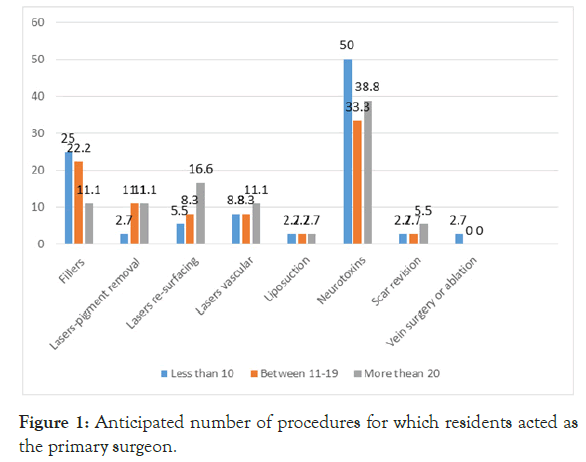

Sixty-three percent of respondents were mainly observer during different cosmetic procedures and 38.8% acted as the primary surgeon while performing neurotoxins procedures. Figure 1 shows anticipated number of procedures for which residents acted as the primary surgeon. Cosmetic treatments provided by residents are most often 44% of no charge. Fifty-two percent of the survey participants perceive their residency program as unsupportive of cosmetic dermatology training, whereas 41% and 5% view their program as neutral or supportive, respectively.

Figure 1: Anticipated number of procedures for which residents acted as the primary surgeon.

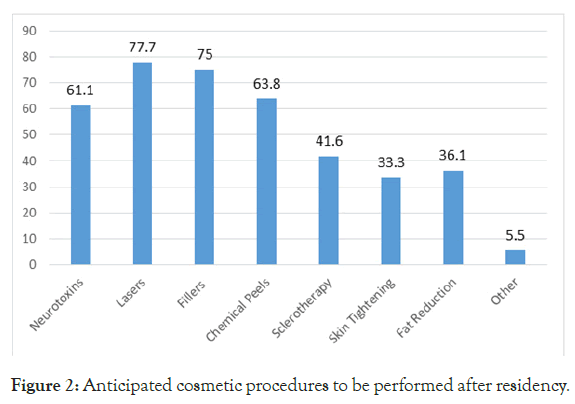

Residents in the cosmetic dermatology program prefer more handson training (61%) in cosmetic dermatology versus lectures (25%) or assigned readings (11%). Sixty-one percent of respondents believed that hands-on cosmetic training during residency as the most effective teaching method which will foster procedural proficiency, followed by lectures (25%), assigned reading (11%) and conference attendance (1%). Participants desire more exposure to fillers (80%), laser treatment and neurotoxins (66%), chemical peels (58%), sclerotherapy (55%), fat reduction techniques and skin-tightening devices (41%) during residency. The participants plan to incorporate cosmetic procedures into their future practice. Anticipated procedures to be performed are shown in Figure 2. Around 91% believe that hands-on cosmetic dermatology training should a requirement during residency.

Figure 2: Anticipated cosmetic procedures to be performed after residency.

This is cross-sectional study that was conducted on thirty six dermatology residents in Saudi Arabia at 2019 at King Abdulaziz University hospital with mean age (27.6 ± 1.9), using electronic self-administrated questionnaire to assess the current stage of cosmetic dermatology training in their residency program. It is noticed that most of the studied participants were female (61.1%), in 2007 female dermatologists represented only 29% of practicing workforce in dermatology in ministry of health and also in private sector in Saudi Arabia [5].

Residency training program of dermatology is differ from one country to another according to their need, in Saudi Arabia duration in the residency program is four years and in United States it is three years and followed by one year internship while in India it is three years followed by two years of diploma [6].

Regarding the year of residency, 33.3% were in the 4th year and 22.2% were in the first year and only 5.5% were recent graduate. Nearly 55.5% of the participants, their residency program were with more than 15 residents and 36.1% of the residents expected to maintain their career after graduation in academic dermatology and 25% were planning for cosmetic dermatology fellowship. Champlain et al. [4] performed study on dermatology residents in United States and Canada using survey that was sent electronically to nearly 1266, showed that about 41% were in the 4th year of their residency program and 52% the size of their program was more than 12 residents.

A survey was developed by Kirby et al. [7], included 26-question was electronically distributed in 2010 to detect the response of both instructors and residents of the dermatology program in United States, 86 responses were collected, about 67% of them had formal lectures, topics of lectures including botulinum toxin injection, lasers, sclerotherapy, chemical peels and soft tissue augmentation, all of the respondents performed botulinum toxin injection and laser, corresponding to Saudi Arabia residency program as about 86% of the studied participants in our study had formal lectures including laser, filler, sclerotherapy and chemical peels while 63% of them were only observer during different cosmetic procedures, while 38.8% performed neurotoxins procedures.

The training in dermatology residency program occurs in different ways and varying attitude of the residents toward the way of training, in this study residents in the cosmetic dermatology program prefer more hands-on training (61%) versus lectures (25%) or assigned readings (11%) while study done by Champlain et al. [4] all the studied participants (100%) received hands-on training in their residency program, also Bauer et al. [8] conducted online survey to assess the attitude of dermatology program directors towards the residency program, the study displayed different attitude of the studied participants towards the cosmetic dermatology program as 38% believed with importance of cosmetic training and only 17% revealed that it is essential to have experience in cosmetic procedure including laser and filler in the first year of residency, and about the program (94%) offered hands on cosmetic training using botulinum toxin and 89%, 47%, 43% provided training with hyaluronic acid, hydroxylapatite and poly-liactic acid fillers.

Regarding the importance of hands-on training experience as part of the residency program, the number of the procedure were quantified in this study, nearly 11.1% performed more than 20 filler procedures, lasers pigment removal, vascular lesion laser and 38.8% of them trained on neurotoxins injection, while only 2.7% recorded less than 10 vein surgery or ablation procedure. Bauer et al. [8], reported 13.7%, 12.1% and 7.7% experienced hands on training with botulinum toxins, vascular laser and skin filler, respectively performed within eight to five procedures.

With development of the cosmetic dermatologic procedure and increasing the gap between the education and practice, most of the residents need more educational training, more researches and more survey will be needed to ensure the best training for both residents and staff to adopt the recent procedures.

The residency training program in Saudi Arabia is similar to many programs that provide hands on cosmetic dermatologic training but there is still lack in the level of participation as a primary surgeon which needs more facilities in both devices and procedures.

Citation: Abduljabbar MH (2021) Cosmetic Dermatology Training Exposure among Saudi Residents: A Cross Sectional Study. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 12:548.

Received: 22-Dec-2020 Accepted: 05-Jan-2021 Published: 12-Jan-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2155-9554.21.s8.548

Copyright: © 2021 Abduljabbar MH. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.