Clinical Pediatrics: Open Access

Open Access

ISSN: 2572-0775

ISSN: 2572-0775

Research Article - (2022)Volume 7, Issue 4

Background: Viral infections trigger type 1 diabetes (T1D) in susceptible children, and may increase incidence of T1D and/or diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) during the COVID-19 pandemic. We aimed to describe the frequency of diabetic ketoacidosis in children and to determine if COVID contribute to the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis.

Objective: To study the incidence of DKA due to new-onset T1D during the COVID-19 pandemic, and whether SARS-CoV-2 infection is a triggering factor for the development of DKA in T1D in Minia university hospital,Egypt.

Methods: This retrospective cohort study of children admitted to PICU and inpatient wards due to new-onset T1D or due to DKA and diagnosed as have positive COVID-19 in Mina University Hospital from 1 April to 31 October 2021. We compared the incidence, number and characteristics of children with newly diagnosed T1D and DKA during the pandemic periods.

Results: An increase in the number of children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes (T1D) has been reported during the COVID-19 pandemic and more children with new-onset T1D now present with severe diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

Conclusion: COVID contribute to the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis and new onset T1D among children.

COVID-19; Children; Diabetes; Infections

Diabetes mellitus is a group of metabolic diseases characterized by chronic hyperglycemia resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both [1]. Diabetes in children usually insulin dependent due to severe insulin deficiency result mostly from immune destruction of Beta cells in pancreas usually after environmental triggers in genetic susceptible children Regarding the pathogenesis of T1D [2], Individuals have an absolute deficiency of insulin secretion and are prone to DKA and most cases are primarily due to T-cell mediated pancreatic islet β-cell destruction, which occurs at a variable rate, and becomes clinically symptomatic when approximately 90% of pancreatic beta cells are destroyed [3].

The environmental triggers (chemical and/or viral) which initiate pancreatic beta cell destruction remain largely unknown, but the process usually begins months to years before the manifestation of clinical symptoms [4]. Enter virus infection has been associated with development of diabetes associated auto-antibodies in some populations [5], and enter viruses have been detected in the islets of individuals with diabetes [6]. In most western countries, T1D accounts for over 90% of childhood and adolescent diabetes [7], although less than half of individuals with T1D are diagnosed before the age of 15 years [8]. Gender differences in incidence are found in some, but not all, populations with more common in males [9]. A seasonal variation in the presentation of new cases is well described, with the peak being in the winter months [10], Despite familial aggregation, which accounts for approximately 10% of cases of type 1 DM (T1D) [9]. Insulin dependent diabetes or TID usually presents with characteristic symptoms such as polyuria, polydipsia, blurring of vision, and weight loss, in association with glycosuria and ketonuria [2]. In most severe form, ketoacidosis [DKA] or rarely a non-ketotic hyperosmolar state may develop and lead to stupor, coma and in absence of effective treatment, death [3].

The diagnosis of DKA is usually confirmed quickly by measurement of a marked elevation of the blood glucose level. In this situation if ketones are present in blood or urine, treatment is urgent [4]. In the absence of symptoms or presence of mild symptoms of diabetes, hyperglycemia detected incidentally or under conditions of acute infective, traumatic, circulatory or other stress may be transitory and should not in itself be regarded as diagnostic of diabetes [5]. The diagnosis of diabetes should not be based on a single plasma glucose concentration. Diagnosis may require continued observation with fasting and/or 2 hour post-prandial blood glucose levels and/or an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), and usually TID diagnosed by found auto antibodies positive [6]. The severe acute respiratory syndrome due to Corona virus 2 (SARS-Cov-2), responsible for the Corona virus disease COVID-19, was first identified in China in 2019 [10].

“Fever of Unknown Origin with pneumonia” had been continuously increasing in Wuhan. The causative agent of this unexplained infected pneumonia was identified as severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) which was not only has a strong human-to-human transmission but also caused severe pneumonia to death [11-15]. Corona viruses are positivestrand ribonucleic, large viruses. Only two genera of the viruses can infect humans: A and B types and they are called human corona viruses (HCoVs) [11].

Common symptoms at the onset of COVID-19 pneumonia for these children included a fever, cough and shortness of breath, whereas less common symptoms were myalgia, malaise, sore throat and diarrhea [16-18]. The impact of SARS-CoV2 on the incidence of new-onset T1D and DKA is unclear [11]. Diabetes has been recognized as a major risk factor for outcomes and mortality in children with COVID-19 [11]. COVID-19 may damage the pancreas or through autoimmune process and initiate the manifestation of diabetes [12].

Diabetes is associated with an increased risk of infections, including viral ones due to defects in the innate immunity affecting phagocytosis, neutrophil chemotaxis, and cell-mediated immunity [13].

Diabetes is associated with endothelial dysfunction and increased platelet aggregation and activation leading to the hypercoagulable state [13] and this is associated with the low-grade chronic inflammation might promote the cytokine storm, a severe complication of COVID-19 which characterized by excessive production of inflammatory cytokines [14].

Furthermore, COVID-19 spike protein gains entry to its target cells by using the Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) as the receptor, which has protective effects primarily regarding inflammation [15]. COVID-19 infection reduces ACE2 expression inducing cellular damage, inflammation, and respiratory failure and can lead to a direct effect on β-cell function, which not only explains that diabetes might be a risk factor for a severe form of COVID-19 disease but also explains that infection could induce new-onset diabetes [16-18].

Besides, most patients present multiple stresses with COVID-19 including respiratory failure and sepsis requiring intravenous infusion of insulin and fluid balance to control the glycemia levels [19]. In addition, potassium balance must be carefully considered in the context of insulin treatment, as hypokalemia is a common feature of COVID-19 and may be exacerbated after the introduction of insulin [19]. In diabetic children’s with COVID, laboratory tests indicated that lymphopenia is also likely to occur. Additionally, increased concentrations of D Dimer and serum ferritin might be one of the clinical manifestations. However, none of these symptoms was present in every patient [20-24]. Radiological, chest CT might have a high diagnostic value because of its typical images of virus infection, high accuracy with a low false negative rate, and time efficiency [24].

Sixty one children were enrolled in this study. The enrolled patients were 2 years to 17 years old fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: Children admitted to Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) with hyperglycemia, Acidosis or Ketosis either known diabetic or newly diagnosed diabetic and have respiratory distress with low O2 saturation. Type 1 diabetes was defined according to autoantibody positivity and by OGT RBG (Random Blood Glucose > 200 mg/dL, FBG (Fasting Blood Glucose>126 mg/dL, and 2 hour postprandial blood glucose>200 mg/dL [1].

DKA was defined according to International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes criteria (blood glucose>11 mmol/L [~200 mg/dL], venous pH<7.3 or bi-carbonate<15 mmol/L, ketonemia and ketonuria) [10]. We evaluate the number of patients diagnosed with T1D, how many had DKA and how many were diagnosed with COVID-19, and how many patients need PICU admission.

Regarding T1D patients were asked about compliance, recuurent admission by DKA and insulin therapy and if there abnormal respiratory manifestations like cough repiratory distress cyanosis or symptoms of infections like fever anorexia headache malaise O2 saturation using pulse oximetery and chest CT were done to all children. Among children with T1D, SARS-CoV-2 was detected by PCR. Children admitted to PICU due to other diseases were excluded from our study. The study conducted according to the principles of helsinki and agreed by the faculty of medicine, Minia University, Ethical committee (No: 116-5-2020). Informed written consents from the patient's caregiver were obtained.

Sample collection

10 ml of venous blood samples were taken for RBG, white blood cells count with differential, HbA1C, and ABG (Arterial Blood Gases) using fully automated chemical auto-analyzer Dimension- ES, USA, also PCR for Corona virus was done.

Statistical analysis

The numerical data were presented as means–standard deviations while non-numerical data were presented as percentage. Two tailed t-tests were used to analyze differences between the control and patients groups. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The magnitude of correlations was determined by Pearson’s correlation coefficient. All the data were analyzed by statistical package Prism 3.0 (Graph Pad software, San Diego, CA, USA).Figures were done by Microsoft Office Excel 2007.

Total number of patients admitted to endocrine unit was 61 by hyperglycemia, thirty eight patients had DKA (Group I) and other twenty three hadn't DKA (Group II). There were no difference between both groups regarding age, sex (p-value <0.190, <0.241respectively) (Table 1).

| Variables | With DKA group I | No DKA group II | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=38 | N=23 | |||

| Age | Median | 6.1 | 7.8 | 0.19 |

| IQR | (1.3-10.2) | (3-11.2) | ||

| Sex | Male | 24(63.2%) | 11(47.8%) | 0.241 |

| Female | 14(36.8%) | 12(52.2%) |

Table 1: Demographic data of patients.

There were significant difference between both groups regarding ABG profile; HCO3 CO2 PO2 (P-value <0.001*, <0.015*, <0.001* respectively). There were significant difference between both groups regarding O2 saturation and Chest CT finding (p-value<0.001*, <0.025* respectively). There were significant difference between both groups regarding severe hyperglycemia and lymphocytes count (p-value<0.010*, <0.035* respectively). There was slight difference between both groups regarding ph-value (p-value=0.492). There were no difference between both groups regarding HbA1C % (p-value=0.496) (Table 2).

| With DKA | No DKA | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=38 | N=23 | |||

| pH | Range | (6.5-11.2) | (7.3-7.5) | 0.492 |

| Mean ± SD | 7.2 ± 1 | 7.4 ± 0 | ||

| HCO3 | Range | (3-23.3) | (16-29.2) | <0.001* |

| Mean ± SD | 9.8 ± 5.6 | 20.3 ± 3.5 | ||

| CO2 | Range | (20-67) | (34.2-46.7) | 0.015* |

| Mean ± SD | 47.7 ± 13.2 | 41.9 ± 3.7 | ||

| PO2 | Range | (45-128) | (20.6-70) | <0.001* |

| Mean ± SD | 93.6 ± 28.1 | 48 ± 13.2 | ||

| RBS | Median | 280 | 209 | 0.010* |

| IQR | (216-501) | (190-240) | ||

| HBA1c% | Range | (8.6-15.6) | (8.9-15.6) | 0.496 |

| Mean ± SD | 11.4 ± 2.5 | 11 ± 2 | ||

| Lymphocytes | Median | 1300 | 2500 | 0.035* |

| IQR | (1000-2500) | (1200-4500) | ||

| Saturation | Range | (49-98.9) | (49-87) | <0.00* |

| Mean ± SD | 85 ± 16.3 | 64.4 ± 9.3 | ||

| Chest CT | -Ve | 26(68.4%) | 9(39.1%) | 0.025* |

| +Ve | 12(31.6%) | 14(60.9%) |

Table 2: Some investigations of patients.

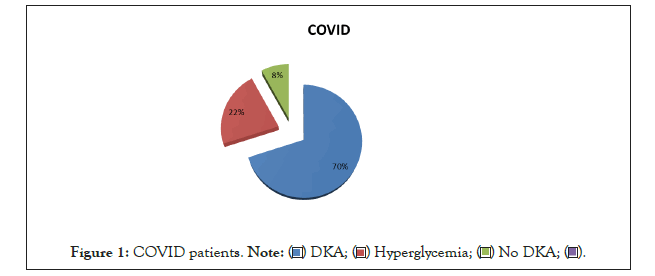

On admission, COVID diagnosed patients were seventy percent were presented by DKA, twenty two % were presented by hyperglycemia only without DKA while only 8% were within normal blood sugar (Figure I).

Figure 1: COVID patients. .

.

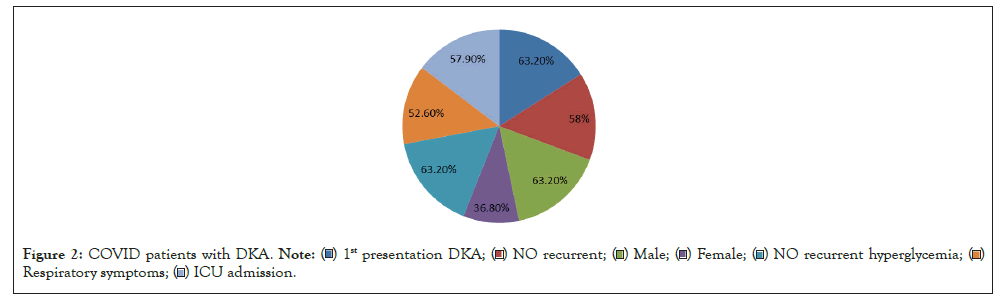

Patients who were diagnosed to have COVID and presented by DKA were 63.20% male and 36.80% female 63.20% of them were presented by new onset diabetes. However, 57.90% need ICU admission and 63.20% of them entre in recurrent hyperglycemia after hospital discharge in three months duration (Figure 2).

Figure 2: COVID patients with DKA.

.

.

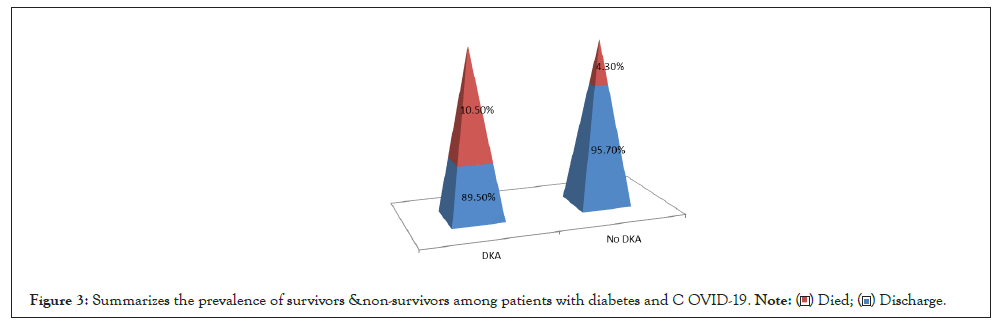

Prevalence of non-survivors among patients with DKA and COVID-19 was 10.50% of patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Summarizes the prevalence of survivors &non-survivors among patients with diabetes and COVID-19. .

.

Data of COVID-19 in children are limited, and clinical manifestations are nonspecific and might delay the diagnosis, which might lead to severe complications. In this clinical case, we describe new-onset diabetes with consciousness impairment as an atypical revealing way of COVID-19 [18].

Diabetes might facilitate infection by COVID-19 due to increased viral entry into cell and impaired immune response. COVID-19 could have effect on the path-physiology of diabetes [20].

Total number of patients admitted to endocrine unit were 61 by hyperglycemia, thirty eight patients had DKA (Group I) and other twenty three hadn't DKA (Group II),There were no difference between both groups regarding age, sex (p-value <0.190, <0.241 respectively).

There were significant difference between both groups regarding ABG profile; HCO3 CO2 PO2 (P-value <0.001*,<0.015*,<0.001* respectively) On admission, COVID diagnosed patients were seventy percent were presented by DKA, twenty two % were presented by hyperglycemia only without DKA while only 8% were within normal blood sugar.

Among children, SARS-CoV-2 was detected by PCR, Patients who were diagnosed to have COVID and presented by DKA were 63.20% male and 36.80% female 63.20% of them were presented by new onset diabetes and this is suggesting that SARS-cov-2 infection was the primary trigger for more severe presentation of T1D and for the increase in children diagnosed with T1D.

This study found of a significant increase in the number (57.90%) of children requiring PICU care for severe ketoacidosis and 63.20% of them entre in recurrent hyperglycemia after hospital discharge in three months duration also found a significant increase in DKA at diabetes diagnosis in children during the COVID-19 pandemic in Minia University Hospital and the increase we observed in the total number of children with new-onset T1D is surprising, and Underlying causes may be multifactorial and reflect reduced medical services, fear of approaching the health care system, and more complex psychosocial factor and this was in agree with Clemens, et al. 2020 study Who explain that there are several precedents for a viral cause of ketosis-prone diabetes, including other corona viruses that bind to ACE2 receptors.

Our study show greater incidences of hyperglycemia and acute-onset diabetes have been reported among patients with SARS corona virus 1 pneumonia than among those with non-SARS pneumonia, in agree with Clemens, et al. study who reported high prevalence of diabetes is seen in patients with COVID-19 and the presence of diabetes is a determinant of severity and mortality. Blood glucose control is important not only for patients who are infected with COVID-19, but also for those without the disease [21].

Guo, et al. reported that hyperglycaemia persist for 3 years after recovery from SARS indicating a transient damage to beta cells [22]. During the observation period, eight % patients were diagnosed with COVID-19, all of whom were asymptomatic or had only mild symptoms and all were positive by PCR with normal blood glucose on admission.

1. Prevalence of survivors and non-survivors among patients with diabetes and COVID-19 during the observation period, only three patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 died from severe respiratory manifestations and there chest imaging showed CORAD 3 due to severe viral load.

Unsworth, et al. found the prevalence of non-survivors was also higher in diabetic subjects with COVID-19

Our findings are in line with recent Italian, German, UK and Australian studies reporting an increased incidence of DKA in children with new-onset T1D during the COVID-19 pandemic [25]. In contrast, a German study reported no increase in the incidence of T1D [26]. As T1D may be triggered by viral infections in susceptible children, the potential association of SARS-CoV-2 with either increasing incidence of T1D or more severe disease presentation needs to be addressed [27].

2. As we noticed that the virus plays a direct role in the increased incidence or more severe presentation of T1D in children.

Delays in the diagnostic process of T1D are likely to explain the increase in the number of children with DKA, as many of the children admitted to the PICU had been symptomatic for longer than the patients in previous months and more complex associations, influencing the threshold of families to seek medical attention and the accessibility of health services, seem to have been involved.

Our results show in a setting with high COVID-19 incidence. With a 70% seropositivity of COVID-19 in children with acute infections in the PICU presented by DKA,and only 22% with hypherglycemia.

Our study suggests that patients of COVID-19 with diabetes are more often associated with severe or critical disease, also Elbarbary et al. in a study of 138 patients reported that 72% patients of COVID-19 with co morbidities including diabetes required admission in ICU, compared to 37% of patients without co morbidities [28].

COVID-19 can result in asymptomatic to severe illness in children. Fortunately, children without underlying chronic illness appeared to have more severe DKA. COVID-19 pandemic might have altered diabetes presentation and DKA severity and requires strategies to educate and reassure parents about timely emergency department attendance for non–COVID-19 symptoms.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Cross ref] [Google scholar] [Pub med]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Cross ref] [Google scholar] [Pub med]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Cross ref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Cross ref] [Google scholar] [Pub med]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pub med]

[Cross ref] [Google scholar] [Pub med]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pub med]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pub med]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pub med]

[Cross ref] [Google scholar] [Pub med]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pub med]

[Cross ref] [Google scholar] [Pub med]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: El Bakry NM, Mohamed AM, Fadl AS (2022) COVID-19 is a Contributing Risk Factor for Development of DKA in Type-I DM: A Cross Sectional Study. Clin Pediatr. 7:210.

Received: 18-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. CPOA-22-16925; Editor assigned: 20-Apr-2022, Pre QC No. CPOA-22-16925 (PQ); Reviewed: 04-May-2022, QC No. CPOA-22-16925; Revised: 09-May-2022, Manuscript No. CPOA-22-16925 (R); Published: 18-May-2022 , DOI: 10.35248/2572-0775.22.7.210

Copyright: © 2022 El Bakry NM, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.