Rheumatology: Current Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2161-1149 (Printed)

ISSN: 2161-1149 (Printed)

Research Article - (2022)Volume 12, Issue 3

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, multisystem, autoimmune disease characterized by periods of increased disease activity caused by inflammation of blood vessels and connective tissue. Pediatric patients with SLE have a more severe clinical course in comparison with their adult counterparts. Compared with adults, children with SLE have more widespread organ involvement. Approximately 20% of all patients who have SLE are diagnosed in childhood. The onset of SLE is rare in those younger than 5 years of age; most pediatric patients are diagnosed in adolescence.

Lupus; Insomnia; Anhedonia; Erythematosus disease

SLE has a more severe clinical course than that seen in adults, with a higher prevalence of lupus nephritis, hematologic anomalies, photosensitivity, neuropsychiatric, and mucocutaneous involvement. Because SLE can present with a number of signs and symptoms, the diagnosis often is considered in children who have prolonged unexplained complaints. Glucocorticoids are the mainstay of pharmacological treatment in patients with SLE with or without major organ involvement. Glucocorticoids are given mainly as oral prednisone, prednisolone, or intravenous high-dose methylprednisolone. Daily doses of glucocorticoids can range from 0.5-2 mg/kg/day. The initial dose is decided by the extent of disease severity and organ involvement. The relationship between chronic physical disease and mental illness is bidirectional. Understanding the relationship between mental and physical health is of utmost importance in pediatric populations, in which both poor physical and mental health outcomes can affect development and lead to long-lasting consequences. The prevalence of depressive symptoms is higher in children with SLE (20%) when compared to their healthy peers (8%) and the general adolescent population (13%). Depression may be the first presentation of juvenile SLE. They may present with sadness, decreased interest in activities, poor communication, and absences from school, fatigue and irritable moods. However, very young children tend not to look depressed but they may present rather with insomnia, weight loss, and increased or new onset of `anxiety symptoms. Anhedonia and social withdrawal are also significant symptoms and are considered a sign of severe illness in a younger child. Depression can have significant lasting effects when diagnosed in childhood and adolescence, and has been associated with later interpersonal difficulties, early parenthood, impaired school performance, unemployment, and other mental disorders and substance use disorders as well as high risk of suicide [1-3]. The aim of this current study was to evaluate the prevalence and severity of depression among pediatric patients with SLE and its relation to disease activity. The correlation between the use of corticosteroids and disease activity was also studied. It was hypothesized that patients with more disease activity would be more depressed.

This study was a cross-sectional, analytical clinical study conducted on 30 SLE patients in activity and another 30 SLE patients not in activity all within an age range of 8 to 12 years (inclusive of 49 females and 11 males). They were recruited from the outpatient clinic of the collagen vascular unit in the Specialized Children Hospital, Cairo University during their regular follow up visit over a 6 months period from April 2019 to October 2020 [2]. The required sample size has been calculated using the Sample Size Calculator for Prevalence Studies (SSCPS) version 1.0.01, which is based on the formula described by Daniel (1999) that is as follows: n=Z*P(1-Pd)2 where n=sample size, Z=Z statistic for the desired level of confidence, p=expected prevalence, and d=level of precision.

The study design and methodology were approved by the scientific research committee of the Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University and also by the Local Ethics Committee of Scientific Research, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University. Before the enrollment in this study, an informed assent from each participant was taken and informed consents from their caregivers were obtained [4].

Clinical history was obtained from the patients that included demographic data as well as Clinical manifestations of SLE including arthritis, malar rash, nephritis, Central Nervous System (CNS) disease, fever, fatigue, weight loss, hair loss, stomach pain, headaches, easy bruising and painful joints. Also, history of prescribed medications including doses like corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, immunosuppressants and pain killers was recorded. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) was used to assess disease activity. It is based on 24 questions assessing the clinical manifestations of SLE which measures manifestations over the past 10 days, including physical findings and laboratory values weighted across organ systems. The final score ranges between 0 and 105. The higher the score, the more significant the degree of disease activity. Scores of 6 and above are considered to be consistent with active disease requiring therapy. General examination of all participants was performed, and their weight, height, BMI and blood pressure were recorded [5]. A detailed chest, cardiac and abdominal examination was also performed. Laboratory tests in the form of CBC, ESR, C3, C4, ANA test, double stranded DNA, Anti double stranded DNA, Anti-smith antibody, CRP, Antiphospholipid antibodies and Circulating lupus anticoagulant were done to all participants.

Depressive symptoms and their severity were assessed using the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) (Arabic version) (2nd edition) which is a self-rated, symptom-oriented scale consisting of 27 groups of statements suitable for assessing depression in youths aged 7 years to 17 years old [6,7]. The statements are related to depressive symptoms including sadness, pessimism, self-depreciation, anhedonia, misbehavior, academic decrement, worrying, self-hate and blame, interpersonal problems, irritability, crying spells and suicidal ideation. On administrating Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), the participants were asked to choose one statement out of the three statements in each group that best described him or her in the past two weeks. It took around 10 minutes to complete.

Statistical analysis

Data were subjected to computer assisted statistical analysis using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) ‖ VERSION 18. Nominal data were expressed as frequency and percentage and were compared using Chi-square test. Numerical data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and were compared using T-test. Nonparametric data were expressed as median-inter quartile range and were compared using Mann Whitney u test. Associations between numerical variables were studied using Pearson’s correlation [8,9]. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Charts and graphs were prepared using Excel or SPSS programs.

Among the 60 patients included in this study 49 patients (81.7%) were females while 11 patients (18.3%) were males. The demographic data of the studied patients are shown in Table1.

| Demographic data of the studied patients | Total Number=60 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean + SD | 10.98+1.30 |

| Range | 08-12 | |

| Sex | Female | 49(81.7%) |

| Male | 11(18.3%) | |

| Residence | Rural | 34(56.7%) |

| Urban | 26(43.3%) | |

Table 1: Demographic data of the studied patients

The clinical manifestations of the studied patients during the course of the disease as shown in Table 2.

| During the course of the disease | Total number=60 | |

|---|---|---|

| Rash | No | 20(33.3%) |

| Yes | 40(66.7%) | |

| Arthralgia | No | 7(11.7%) |

| Yes | 53(88.3%) | |

| Fever | No | 23(38.3%) |

| Yes | 37(61.7%) | |

| Hair loss | No | 31(51.7%) |

| Yes | 29(48.3%) | |

| Seizures | No | 49(81.7%) |

| Yes | 11 (18.3%) | |

| Serositis | No | 53(88.3%) |

| Yes | 7(11.7%) | |

| Nephritis | No | 33(55.0%) |

| Yes | 27(45.0%) | |

| Photosensitivity | No | 52(86.7%) |

| Yes | 8(13.3%) | |

| Vasculitis | No | 52(86.7%) |

| Yes | 8(13.3%) | |

| Oral ulcer | No | 56(93.3%) |

| Yes | 4(6.7%) | |

Table 2: Clinical manifestations of the studied patients.

Patients were divided into 2 groups: 30 patients in activity and 30 patients not in activity according to SLEDAI. Regarding steroid therapy, 52 patients were receiving steroids, 34 patients (65.4%) were on high dose steroids while 18 patients(34.6%) were on low dose steroids (0.25-1 mg/kg). There was no statistically significant relation difference found between active group and inactive group regarding age (10.9 ± 1.4 versus 11.07 ± 1.2 with p-value=0.622) [10]. Also, there was no statistically significant difference found between active group and inactive group regarding sex of the studied patients with p-value=0.317as shown in Table 3.

|

Inactive group | Active group | Test value | p-value | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number=30 | Number=30 | |||||

| Age(years) | Mean ± SD | 10.90 ± 1.40 | 11.07 ± 1.20 | -0.495 |

0.622 | NS |

| Range | 8-12 | 8-12 | ||||

| Sex | Female | 7(23.3%) | 26(86.7%) | 1.002* | 0.317 | NS |

| Male | 7(13.3%) | 4(13.3%) | ||||

Note: p-value>0.05:Non-significant; p-value<0.05: Significant; p-value<0.01: Highly-significant; *: Chi-square test;  : Independent T-test

: Independent T-test

Table 3: Significant difference found between active group and inactive group regarding sex of the studied patients.

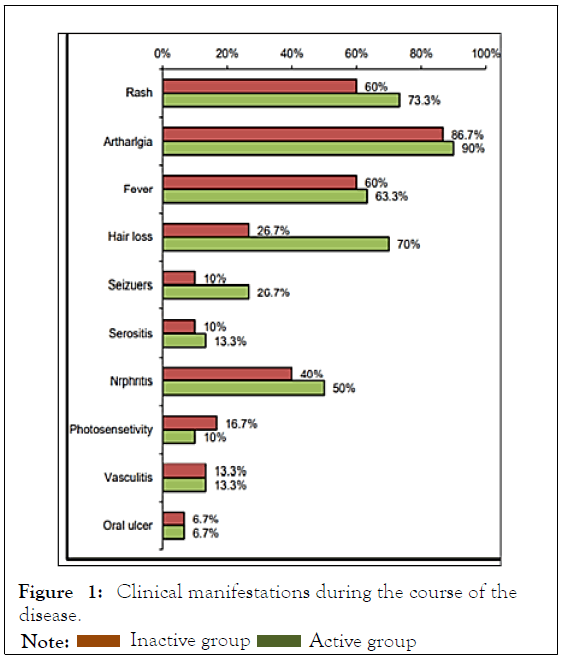

No statistically significant relation was found between activity of the studied patients and clinical manifestations during the course of the disease except hair loss was found significantly associated with activity among the studied patients with pvalue= 0.001 as shown in Figure 1. There was no statistically significant relation between activity of the studied patients and medications used in reatment of SLE except steroids and the the dose of steroids used, which were found to be steroids associated with activity among the studied patients with p-value=0.001, 0.003 respectively [11-13].

Figure 1: Clinical manifestations during the course of the

disease.

The current study showed that, there was no statistically significant difference found between active group and inactive group regarding age (10.9 ± 1.4 versus 11.07 ± 1.2 with pvalue= 0.622) and regarding the sex of the studied patients with p-value=0.317. Similarly in study conducted by Mok et al. activity was measured by the SLEDAI [11]. At the time of diagnosis, there was a trend, but not a statistically significant difference, between both gender in the signs of disease activity although the males had less arthritis, alopecia, anti-Ro antibody, less Raynaud‘s, and more discoid lesions and thrombocytopenia. While in contrast, de Carvalho et al. found male patients had higher activity scores [12]. The current study showed that, there was no significant difference between the active and inactive group in clinical manifestations at the onset of the disease except hair loss, serositis and vasculitis were found to be significantly associated with activity among the studied patients with p-value=0.001, 0.038 and 0.038 respectively. At the course of the disease, there was no significant difference between the active and inactive group in clinical manifestations during the course of disease except hair loss which was significantly associated with activity among the studied patients with p-value=0.001. In agreement with us Bouaziz et al. found the presence of vasculitic lesions to be strongly related to systemic disease activity [13]. Also, in harmony with our results, Callen and Kingman reported a link between cutaneous vasculitis and the progression of disease. On the other hand, Nazri et al. found oral ulcers (p=0.010) and malar rash (p=0.044) to be positively associated with an active disease [15]. Our results were against the Houman et al. finding as they found the SLEDAI score for activity at SLE diagnosis was significantly higher in patients with lupus nephritis [14].

The current study showed that, there was no significant difference between the active and inactive group in medications used in treatment of SLE except steroids and the dose of steroids which were found to be significantly associated with activity among the studied patients with p-value=0.001 and 0.033 respectively. In agreement with us Alsowaida et al. found no relation between medication non-adherence and disease activity [6]. This finding was also supported by the study conducted by Petri et al. as none of the baseline medications evaluated, including corticosteroids, immunosuppressives (individually as a group), antimalarials, and other concomitant medications, predicted flare on any index but their results was against us regarding steroid uses [15].

Children with SLE in active disease have a greater risk of developing depression than those with inactive disease and the severity of depression is positively correlated with disease activity. The findings from this study confirm the importance of identifying and managing depression in SLE. The data indicate that depression may exacerbate lupus disease activity and suggest that effective treatment of depression may lead to improvements in lupus disease outcomes. Recognition of these associations may provide more appropriate management for these patients and also may bring new insights to the understanding of the underlying mechanism involved in this important clinical presentation of SLE.

Citation: Haroun M, Osman HT, Halim SH, Samie MA (2022) Depression in Children with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Correlation with Disease Activity. Rheumatology (Sunnyvale). 12:302.

Received: 04-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. RCR-22-17015; Editor assigned: 08-Apr-2022, Pre QC No. RCR-22-17015 (PQ); Reviewed: 22-Apr-2022, QC No. RCR-22-17015; Revised: 29-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. RCR-22-17015 (R); Published: 04-May-2022 , DOI: 10.35841/2161-1149.22.12.302

Copyright: © 2022 Haroun M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.