Journal of Women's Health Care

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0420

ISSN: 2167-0420

Research Article - (2023)Volume 12, Issue 7

Background: Due to their dread of this pandemic, which directly threatens both the mother's and baby's health, most pregnant women skip out on their prenatal appointments and deliveries at medical facilities.

Objectives: Assessing knowledge, preventive practice, and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care towards COVID-19 at public health facilities of east Gojjam zone, 2020.

Methods: Between December 1 and December 30, 2020, 847 pregnant women participated in a multi-center cross sectional study. The sampling process involved multiple stages. A pre-tested interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect the data, which were then input into Epi Data version 4.6 and analyzed using SPSS version 25. To investigate the relationships between knowledge, COVID-19 prevention practices, and predictor variables, bivariable and multivariable logistic regression models were used. Statistical significance was determined using an odds ratio with a 95 percent confidence level and a P-value of 0.05.

Results: Of 806 study participants, 416 (51.6%) 95% CI (48.15, 55.05), and 354 (43.9%) with 95% CI (40.47, 47.33). of pregnant women had adequate knowledge and good preventive practice against COVID-19 pandemic respectively. Urban residents (AOR=1.91, 95 CI: 1.30-2.79), civil servant (AOR=2.29, 95% CI: 1.20-4.37), secondary school and college and above (AOR=1.96, 95% CI: 1.14 - 3.40), and (AOR= 2.97, 95% CI: 1.56 - 5.65), favorable attitude (AOR=2.10, 95% CI: 1.51-2.91) were the predictors of knowledge towards Corona virus infection. Urban residents (AOR=1.54, 95% CI: 1.07-2.22), civil servant (AOR=1.81, 95% CI: 1.02 - 3.20), merchant (AOR=1.86, 95% CI: 1.16 - 2.99), and employed in private (AOR=1.97, 95% CI: 1.07 - 3.64), had medical problems (AOR=1.69, 95% CI: 1.07-2.65), adequate knowledge (AOR=1.67, 95% CI: 1.23-2.28) and favorable attitude (AOR=1.74, 95% CI: 1.26-2.42) were positively associated factors against Corona virus pandemic.

Conclusions and recommendations: Attendees at ANC had a generally adequate level of general awareness of pregnant women, but there was a poor application of these COVID-19 prevention strategies. To break the chain of transmission, increased education and implementation of preventive measures will be necessary. Continuous mass media program mobilization and health education for people with medical issues, no formal education, housewives, and rural residents should be taken into account.

Corona virus, Knowledge, Pregnant woman, Preventive practice, Ethiopia

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is a disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome, which exponentially increases in the world among infected persons [1]. In Wuhan, China majority (64.6%) of the pregnant women were absent from their antenatal follow-up and did not use all the personal protective equipment as a preventive measure [2]. Even though the virus affects all groups of people, pregnant women are particularly vulnerable due to physiological changes and impaired cellular immunity during pregnancy, which increases the risk of respiratory infection [3, 4].

Pregnant women face preterm delivery due to COVID-19, and preventive measures should be considered [5, 6].

Restricting movements, physical distancing, routine screening, isolation of infected persons, using sanitizers, hand hygiene, environmental monitoring, and appropriate use of personal protective equipment like face masks are the recommended WHO and international labour organization preventative measures for COVID-19 [7]. COVID 19 imposes stress and depression among pregnant women resulting in miscarriage, preterm birth, low birth weight, and fetal death [8]. When pregnant women become infected, they require more hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, and mechanical ventilation, which affect the mode of delivery and breastfeeding and increase the physical burden of the pregnancy, resulting in psychological-emotional challenges [9]. This virus makes black pregnant women more worried about their receiving antenatal care, access to food, medication, birth experience, and baby care [10].

In low and middle-income countries, COVID 19 affects maternal and newborn health by decreasing the number of pregnant women attending prenatal care and institutional delivery [11]. The knowledge of pregnant women aids in reducing the negative attitude of the clients and increasing pandemic prevention measures [12]. Since knowledge regarding the pandemic is the determinant factor for pregnant women, health education to alleviate the fear of the pandemic is mandatory to achieve a successful pregnancy [13]. Adherence to COVID 19 preventive measures among pregnant women is insufficient. So, awareness creation through media and health education is necessary [14, 15].

Therefore, the study aimed to knowledge, preventive practice, and associated factors towards COVID-19 among pregnant mothers attending antenatal care at public health facilities in East Gojjam Zone.

Study Setting, Design and Period

An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted from December 1-30, 2020 in public health facilities of the East Gojjam zone in the Amhara regional state. With population projection from the 2007 census, East Gojjam Zone has a total population of 2,153,937, of whom 1,066,716 are men, 1,087,221 are women. East Gojjam Zone has been divided into 19 districts and 468 kebeles. The zone had ten (10) hospitals, 103 health centers, and 423 health posts. Of these, one general and one comprehensive specialized hospital are available.

Sample Size determination

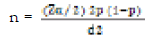

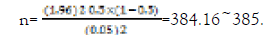

The sample size of the study was determined by using a single population proportion formula based on the following assumptions.

Where: n= is desired sample size

Where: n= is desired sample size

Zα/2= is the critical value corresponding to the desired level of the confidence interval of 95% (Zα/2=1.96).

d=margin of error = 5 % (0.05)

P=is the estimated population proportion take p as 50%.

Considering design effect 2 and 10% non-response rate, the final sample size was 847.

Sampling Technique and Procedure

A multistage sampling technique was used. There are 103 health centers, 8 primary hospitals, and 1 general and comprehensive specialized hospital in the study area. First, stratification was done based on the level of the health facility. Then one-third from each type of health facility was taken by simple random sampling technique using a lottery method. Then, the proportional allocation for each health facility was done to allocate the sample size based on the case flow seen in the last month's registration report. Finally, each study participant was selected using a systematic sampling technique for every 2nd pregnant woman after selecting randomly the 1st sample from 1 and 2.

Measurements and Operational Definitions

The dependent variables were knowledge and preventive practice regarding COVID-19. Adequate knowledge among pregnant women was considered when pregnant women scored greater than or equal to the mean values of knowledge-related questions. Pregnant women who scored greater than or equal to the mean values of practice-related questions had good preventive practice about COVID 19.

Data Collection Tools and Procedures

An interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect data from study participants. The questionnaire was adapted from reviewed literature [16-19] with modification and contextualized into the local setting. The questionnaires consist of sociodemographic characteristics, obstetrics and reproductive history of study participants, and knowledge and practice assessment questions regarding Covid-19 pandemic disease. Under the supervision of MSc midwives, BSc midwives collected the study's data.

Data Quality Control

Emphasis was given to the data collection to assure the data quality. The questionnaire was first written in English, then translated into the study participants' native tongue, Amharic, and finally back into English. Before data collection, the supervisors and data collectors received training. A pre-test was conducted on 5% of the estimated sample size at Finote Selam General Hospital, which shares sociodemographic characteristics with our study group, to evaluate the suitability of phrasing, clarity of the questions, and responder attitude to the questions and interviewer. The questionnaire was reviewed, and confirmed for completion.

Data Processing and Analysis

The collected data were rechecked, coded, and entered into a computer by EpiData version 4.6. And exported to SPSS version 25.0 for analysis. Descriptive statistics were computed to determine frequencies and summary statistics (percentage) to describe the study population about socio-demographic and other relevant variables. Data were presented using tables and figures. Bivariable logistic regression was used to check variables having an association with the dependent variable, and then those variables having a p-value of≤0.25 were fitted to multivariable logistic regression for controlling the effects of confounders. A P-value of <0.05 with a 95% confidence level was used to declare a significant association of independent variables with the dependent variable. The model fitness was checked by the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test.

Ethical Consideration

The ethical review committee for the College of Health Sciences at Debre Markos University granted its approval. The formal letter from the institutional review committee of health Science College has been summited to Amhara regional health bureau, and this body sent the letter to the Zonal health bureau. The East Gojjam zone health bureau granted permission to the concerned bodies of the health facilities. After providing respondents with information about the study, they provided informed written consent. A legally recognized representative of people less than 18 also provided written informed consent. The confidentiality of the study participants was kept anonymous.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

Out of 847 sampled pregnant women, 806 responded to the questionnaires making a response rate of 95.2%. The majority of 285 (35.4%) study participants were aged between 25-29 years. The mean age of study participants was 27.57 ±6.080 years. 763(94.6%) of the study participants were married. More than half, 426 (52.9) of the study participants were urban residents. About 42.6% of study participants didn’t attend formal education. Nearly half of 329 (40.8%) of the study participants reported their monthly income worsened in the past three months before the study [Table 1].

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15-19 | 59 | 7.3 |

| 20-24 | 199 | 24.7 | |

| 25-29 | 285 | 35.4 | |

| 30-34 | 130 | 16.1 | |

| =35 | 133 | 16.5 | |

| Marital status | Married | 763 | 94.6 |

| Divorced | 15 | 1.9 | |

| Single | 4 | 0.5 | |

| Widowed | 24 | 3 | |

| Residence | Rural | 380 | 47.1 |

| Urban | 426 | 52.9 | |

| Level of education | No formal education | 343 | 42.6 |

| Primary | 169 | 21 | |

| Secondary | 105 | 13 | |

| Diploma and above* | 189 | 23.4 | |

| Occupation | Housewife | 498 | 61.8 |

| Civil servant | 148 | 18.4 | |

| Private business | 103 | 12.8 | |

| Private employee | 57 | 7 | |

| Average Monthly income | =1000 | 126 | 15.6 |

| 1001-3000 | 386 | 47.9 | |

| 3001-10000 | 292 | 36.2 | |

| >10000 | 2 | 0.2 | |

| Situation of monthly income in the past three months | Worsened | 329 | 40.8 |

| Improve | 98 | 12.2 | |

| Remain the same | 379 | 47 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant women attending ANC at public health facilities of East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020(n =806).

Obstetrics and reproductive history of study participants

This study reported that about 501 (62.2%) and 327 (40.6%) study participants were multigravidas and nulliparous, respectively. Regarding the condition of abortion, about 70 (8.7%) of respondents had a history of abortion [Table 2].

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gravidity | Primigravida | 305 | 37.8 |

| Multigravida | 501 | 62.2 | |

| Gestational age | <37 wks. | 739 | 91.7 |

| = 37 wks. | 67 | 8.3 | |

| Parity | Nulliparous | 327 | 40.6 |

| Primipara | 170 | 21.1 | |

| Multipara | 309 | 38.3 | |

| Number of children | < 3 | 552 | 68.5 |

| =3 | 254 | 31.5 | |

| History of abortion | Yes | 736 | 91.3 |

| No | 70 | 8.7 |

Table 2: Obstetrics related characteristics of pregnant women attending ANC at public health facilities of East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020(n =806).

Knowledge of study participants towards COVID-19 pandemic

This study revealed that 416 (51.6%) pregnant women had adequate knowledge about the COVID-19 pandemic with 95% CI (48.15, 55.05). Each study participant (100%) had heard of COVID-19, and about four-fifth (81.6%) of them knew that it is a viral disease. More than ninety (90.3%) of the participants said that COVID-19 could not transmit during breastfeeding. Fever, cough, and headache were the three COVID-19 symptoms were most frequently mentioned by 67%, 68.6%, and 38.3% of respondents, respectively [Table 3].

| Knowledge on COVID-19 | Response | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever heard about COVID-19 | Yes | 806 | 100 |

| No | 0 | 0 | |

| COVID-19 is a viral disease | Yes | 658 | 81.6 |

| No | 148 | 18.4 | |

| Knowledge on transmission COVID-19* | |||

| Coughing /sneezing | Yes | 490 | 60.8 |

| No | 316 | 39.2 | |

| Direct contact with COVID-19 patient | Yes | 470 | 58.3 |

| No | 336 | 41.7 | |

| Eating contaminated meat/food items | Yes | 249 | 30.9 |

| No | 557 | 69.1 | |

| Mother to the fetus during pregnancy |

Yes | 142 | 17.6 |

| No | 664 | 82.4 | |

| During breast feeding | Yes | 78 | 9.7 |

| No | 728 | 90.3 | |

| Person with COVID-19 can transmit to others without development of manifestations | Yes | 171 | 21.2 |

| No | 635 | 78.8 | |

| Incubation period 2-14 days | Yes | 243 | 30.1 |

| No | 563 | 69.9 | |

| Knowledge on risk perception of COVID-19* | |||

| Pregnant women are at high risk than others if infected with COVID-19 | Yes | 282 | 31.5 |

| No | 524 | 68.5 | |

| Patients with co-morbidities disease are at high risk than others if infected with covid-19 | Yes | 435 | 54 |

| No | 371 | 46 | |

| Children individuals are high risk than others if infected with covid-19 | Yes | 254 | 21.2 |

| No | 552 | 78.8 | |

| Older people are high risk than others if infected with covid-19 | Yes | 400 | 49.6 |

| No | 406 | 50.4 | |

| Knowledge of signs and symptoms of COVID-19* | |||

| Fever | Yes | 540 | 67 |

| No | 266 | 33 | |

| Cough | Yes | 553 | 68.6 |

| No | 253 | 31.4 | |

| Headache | Yes | 309 | 38.3 |

| No | 497 | 61.7 | |

| Sore throat | Yes | 149 | 18.5 |

| No | 657 | 81.5 | |

| Runny nose | Yes | 160 | 19.9 |

| No | 646 | 80.1 | |

| Difficulty breathing | Yes | 283 | 35.1 |

| No | 523 | 64.9 | |

| Diarrhea | Yes | 66 | 8.2 |

| No | 740 | 91.8 | |

| Knowledge of preventive measures* | |||

| Frequent hand washing with water and soap/ alcohol based hand sanitizer | Yes | 502 | 62.3 |

| No | 304 | 37.7 | |

| Avoid unnecessary travel | Yes | 471 | 58.4 |

| No | 335 | 41.6 | |

| Avoid close contact with an infected one | Yes | 574 | 71.2 |

| No | 232 | 28.8 | |

| Avoid touching your eye, nose, mouth with unwashed hands | Yes | 508 | 63 |

| No | 298 | 37 | |

| Wear mask in public | Yes | 517 | 64.1 |

| No | 289 | 35.9 | |

| Avoid crowded place | Yes | 483 | 59.9 |

| No | 323 | 40.1 | |

| Cure of COVID-19 | Yes | 137 | 17 |

| No | 669 | 83 | |

| Vaccine of COVID-19 | Yes | 237 | 29.4 |

| No | 569 | 70.6 | |

Table 3: COVID-19 knowledge of pregnant women attending ANC at public health facilities of East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020(n =806).

Practice of pregnant women against COVID-19 prevention

Of 806 pregnant women interviewed about COVID-19 preventive measures, 514 (63.8%) wash their hands using soap and water, 410 (50.1%) wear a face mask when they were in public congregation, 156 (19.4%) kept their social distance, and 361 (44.8%) did not participate in public meetings. This study also reported that 354 (43.9%) pregnant women had good preventive practices for COVID-19. with 95% CI (40.47, 47.33) [Table 4].

| Practice related questionnaires | Response | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wash hand with soap and water / hand rub with sanitizers? | Yes | 514 | 63.8 |

| No | 292 | 36.2 | |

| Wear face Mask in public | Yes | 410 | 50.1 |

| No | 396 | 49.1 | |

| Avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth unwashed hand | Yes | 309 | 38.3 |

| No | 497 | 61.7 | |

| Avoiding hand shaking with others | Yes | 408 | 50.6 |

| No | 398 | 49.4 | |

| Covering mouth and nose during coughing or sneezing | Yes | 410 | 50.9 |

| No | 396 | 49.1 | |

| Stay at home during the transmission period | Yes | 277 | 34.4 |

| No | 529 | 65.6 | |

| Throw the tissue in the trash | Yes | 403 | 50 |

| No | 403 | 50 | |

| Maintain at least 2-meter distance from others | Yes | 156 | 19.4 |

| No | 650 | 80.6 | |

| Don’t participate in public meetings | Yes | 361 | 44.8 |

| No | 445 | 55.2 |

Table 4: Practice towards COVID-19 preventive measures among pregnant women attending ANC at public health facilities of East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020(n =806).

Factors associated with knowledge of pregnant women

In this study, the odds of having good knowledge of COVID-19 among pregnant women who were residing in urban settings had 1.91 times better knowledge of COVID-19 compared to pregnant women who were living in rural areas (AOR=1.91, 95 CI: 1.30- 2.79).

In the current study, the odds of having good knowledge of COVID-19 among pregnant women who were civil servants were 2.29 times more likely compared to pregnant women having other occupations (AOR=2.29, 95% CI: 1.20-4.37).

Based on educational status, the odds of having good knowledge of COVID 19 among pregnant women who had an educational level of secondary school and college and above were 1.96 and 2.97 times more likely as compared to those who had no formal education (AOR=1.96, 95% CI: 1.14 - 3.40), and (AOR= 2.97, 95% CI: 1.56 - 5.65) respectively.

The present study revealed that the odds of having good knowledge about COVID 19 among pregnant women who had a favourable attitude were 2.10 times more likely than their counterparts (AOR=2.10, 95% CI: 1.51-2.91) [Table 5].

| Characteristics | Knowledge | COR (95%) | AOR (95%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Residence | |||||

| Rural | 139 | 241 | 1 | 1 | |

| Urban | 277 | 149 | 3.22(2.42 - 4.30) | 1.98(1.30 - 2.79) | 0.001* |

| Age of women | |||||

| 15-19 | 27 | 33 | 1.45(0.78 - 2.69) | 1.04(0.46-2.35) | 0.931 |

| 20-24 | 107 | 93 | 2.04(1.30 - 3.20) | 1.08 (0.58-2.01) | 0. 819 |

| 25-29 | 161 | 122 | 2.34(1.53 - 3.57) | 1.30 (0.76-2.24) | 0.341 |

| 30-34 | 73 | 57 | 2.27(1.38 - 3.72) | 1.46(0.83-2.60) | 0.192 |

| =35 | 48 | 85 | 1 | 1 | |

| Occupation | |||||

| Housewife | 199 | 297 | 1 | 1 | |

| Civil servant | 127 | 24 | 7.90(4.93-12.66) | 2.29(1.20-4.37) | 0.012* |

| Merchant | 55 | 48 | 1.71(1.12 - 2.62) | 1.03(0.63-1.68) | 0.91 |

| Employed in private | 35 | 21 | 2.49(1.41 -4.40) | 1.62(0.85-3.07) | 0.142 |

| Educational status | |||||

| No attending formal education | 118 | 225 | 1 | 1 | |

| Primary | 76 | 94 | 1.54(1.06 - 2.24) | 1.07(0.69 - 1.67) | 0.764 |

| Secondary | 66 | 39 | 3.23(2.05 -5.08) | 1.96(1.14 -3.40) | 0.015* |

| College and above* | 156 | 32 | 9.30(5.98 - 14.45) | 2.97(1.56 - 5.65) | 0.001* |

| Gravidity | |||||

| Primigravida | 176 | 129 | 1.48(1.11-1.98) | 1.47(0.68-3.16) | 0.323 |

| Multigravida | 240 | 261 | 1 | 1 | |

| GA in weeks | |||||

| <37 wks. | 376 | 363 | 0.67(0.51 - 0.90) | 0.99(0.52-1.86) | 0.965 |

| = 37 wks. | 41 | 26 | 1 | 1 | |

| Parity | |||||

| Nulliparous | 186 | 141 | 1.79(1.31 - 2.45) | 0.77(0.34 -1.74) | 0.535 |

| Primipara | 99 | 71 | 1.90(1.30- 2.77) | 1.21(0.74 - 1.97) | 0.456 |

| Multipara | 131 | 178 | 1 | 1 | |

| Number of alive children | |||||

| < 3 | 233 | 319 | 3.53(2.56 - 4.87) | 3.62 (0.52 -5.20) | 0.426 |

| =3 | 183 | 71 | 1 | 1 | |

| Attitude | |||||

| Favorable | 254 | 158 | 2.30(1.74 - 3.053) | 2.10(1.51-2.91) | 0.000* |

| Unfavorable | 162 | 232 | 1 | 1 | |

Table 5: Bivariate and Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis on Factors Associated with COVID-19 knowledge of pregnant women attending ANC at public health facilities of East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020 (n =806).

Associated factors of COVID-19 preventive practice

Pregnant urban residents were 1.54 times more likely than nonurban residents to have good COVID-19 pandemic prevention practices (AOR=1.54, 95% CI: 1.07-2.22).

This study showed that the odds of having good prevention practices for COVID 19 among pregnant women who were civil servants (AOR=1.81, 95% CI: 1.02 - 3.20), merchants (AOR=1.86, 95% CI: 1.16 - 2.99), and others (AOR=1.97, 95% CI: 1.07 - 3.64) had 1.81, 1.86 and 1.97 times more likely as compared to pregnant women who were housewife respectively.

The odds of having good preventive practice for COVID 19 among pregnant women who had medical problems had 1.69 times more likely than their counterparts (AOR=1.69, 95% CI: 1.07-2.65)

In the present study, the odds of having good preventive practices about COVID-19 among pregnant women who had adequate knowledge had 1.67 times more likely compared to those who had inadequate knowledge of COVID-19 (AOR=1.67, 95% CI: 1.23-2.28).

The odds of Pregnant women who had favourable attitude had 1.74 times better preventive practice towards COVID-19 compared to pregnant women who had unfavourable attitude (AOR=1.74, 95% CI: 1.26-2.42) [Table 6].

| Variables | Practice of pregnant women | COR (95%) | AOR (95%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Residence | |||||

| Rural | 260 | 120 | 1 | 1 | |

| Urban | 192 | 234 | 2.64 (1.98 - 3.52) | 1.54(1.07-2.22) | 0.020* |

| Age of women | |||||

| 15-19 | 23 | 37 | 1.07(0.57-1.20) | 0.60 (0.27 - 1.30) | 0.193 |

| 20-24 | 87 | 113 | 1.32(0.84 - 2.07 ) | 0.72 (0.40 - 1.31) | 0.285 |

| 25-29 | 144 | 139 | 1.78(1.16-2.71 ) | 1.06 (0.64 - 1.78) | 0.817 |

| 30-34 | 51 | 79 | 1.11( 0.67-1.82) | 0.72 (0.42 - 1.24) | 0.235 |

| =35 | 49 | 84 | 1 | 1 | |

| Occupation | |||||

| Housewife | 169 | 327 | 1 | 1 | |

| Civil servant | 97 | 54 | 3.48 (2.37 -5.09) | 1.81(1.02 - 3.20) | 0.043* |

| Merchant | 56 | 47 | 3.05(1.500 - 3.54) | 1.86(1.16 - 2.99) | 0.010* |

| Private employee | 32 | 24 | 2.58 (1.47- 4.52) | 1.97(1.07 - 3.64) | 0.030* |

| Educational status | |||||

| No formal education | 108 | 235 | 1 | 1 | |

| Primary | 73 | 97 | 1.64(1.12 -2.39) | 1.16 (.76-1.79) | 0.493 |

| Secondary | 52 | 53 | 2.14(1.37-3.33) | 1.19(0.70-2.01 | 0.525 |

| Gravidity | |||||

| Primigravida | 155 | 150 | 1.57 (1.18- 2.09) | 0.68 (0.34 -1.40) | 0.297 |

| Multigravida | 199 | 302 | 1 | 1 | |

| Parity | |||||

| Nulliparous | 170 | 157 | 1.83(1.33-2.51) | 2.11(0.98- 4.55) | 0.56 |

| Primipara | 69 | 101 | 1.15(0.77 - 1.69) | 0. 714(0.45-1.15) | 0.162 |

| Multipara | 115 | 194 | 1 | 1 | |

| Medical problem | |||||

| Yes | 53 | 49 | 1.45(0.96-2.20) | 1.69(1.07-2.65) | 0.024* |

| No | 301 | 403 | 1 | 1 | |

| Overall knowledge | |||||

| Adequate | 230 | 186 | 2.65 (1.99- 3.54) | 1.67(1.23-2.28) | 0.001* |

| Inadequate | 124 | 266 | 1 | 1 | |

| Attitude | |||||

| Favorable | 215 | 197 | 2.00 (1.51 - 2.66) | 1.74(1.26-2.42) | 0.001* |

| Unfavorable | 139 | 255 | 1 | 1 | |

Table 6: Bivariable and Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis on Factors Associated with COVID-19 preventive measures among pregnant women attending ANC at public health facilities of East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020(n =806).

In Ethiopia, under the current SDG period, the welfare of mothers, newborns, and children remains a top priority for the health sector, but a significant proportion of women did not use maternity healthcare services. Having this insight in mind, we conducted. A multi-center institution-based cross-sectional study aimed to determine knowledge and preventive practice of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated factors among pregnant women attending ANC at public health facilities of East Gojjam Zone.

The proportion of pregnant women's knowledge of COVID-19 was 51.6% (95% CI 48.2, 55.1). This result is in line with the study conducted in Gondar (55%) [20], Gurage (54.84%) [21], and India (50.5%) [22].

The present study was lower than the study conducted in Wollega (75.4%) [23], Egypt (57.6%) [24], low-resource African setting (60.9%) [25], and Indian defense hospital (75.3%) [26].

This discrepancy might be the difference in socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants compared to other studies, as the majority of respondents in this study didn’t attend formal education that directly affects the level of knowledge.

On the other hand, this finding was higher than the study done in Debre Tabor (46.8%) [27], South Africa (43.5%) [28], and Iraq (28%) [29] This discrepancy might be due to the difference in the study setting. The present study was facility-based compared to the study done in Debre Tabor [27]. When pregnant women go to health institutions, they get the opportunity to have some information regarding the pandemic during their ANC followup. Furthermore, more than half of the study's participants were urban residents who could easily update themselves on COVID-19 through social media and mass media.

Urban resident pregnant women were 1.91 times more likely to be knowledgeable about COVID-19 than their counterparts. This could be because urban residents have greater access to new information and update themselves through various media than rural residents. Studies from Wollega, Ethiopia [23] and India [26] supported this finding.

Regarding occupation, civil servants pregnant women were 2.29 times more likely than housewives to be knowledgeable about the COVID-19 pandemic. The possible reason for this might be civil servants pregnant women are employed, educated, and work in close collaboration with the government of direction to reduce the burden of this pandemic, which increases their knowledge. The study conducted in Debre Tabor, Ethiopia [27] supported the finding.

Participants who completed secondary school and college and above were 1.96 and 2.97 times more knowledgeable about COVID-19 than those who did not attend formal education, respectively. The possible reason for this might be education is crucial and one of the most determinant factors to know and understand fruitfully. Educated pregnant women can search, read, and follow social media, which contributed to increased knowledge about the pandemic. The finding is supported by studies in [27], Wollega [23], and India [26].

Pregnant women with a favorable attitude were 2.1 times more likely than those with an unfavorable attitude to be knowledgeable about the COVID-19 pandemic. The possible evidence for this might be that the pregnant women's positive attitude makes them curious about coronavirus.

The study reported that 354 (43.9%) with 95% CI (40.5, 47.3) pregnant women had good preventive practices for COVID-19. This is in line with the study conducted in Wollega (43.6%) [23]. But this finding is lower than studies from Debre Tabor (47.6%) [27], Gondar (47.4%) [20], Guraghe (76.2%) [21], South Africa (76%) [28], Defense Hospital India (92.7%) [26] and another study in India (69.8%) [22]. In low-income countries such as Ethiopia, a lack of knowledge and access to resources leads to poor pandemic prevention practices. Variations in pregnant women's social lives across countries may have contributed to the discrepancy.

The present study was higher than the study conducted in Egypt (12.4%) [24], low-resource African setting (30.3%) [25], and Iraq 32.75%) [29]. The disparity could be attributed to a difference in the study period, as this study was conducted during the peak of COVID-19 in the country, causing pregnant women to be concerned about becoming infected and taking appropriate COVID-19 pandemic precautions. Furthermore, the majority of study participants' previous studies were farmers and rural residents, which may result in poor prevention practice due to a lack of awareness about the COVID-19 pandemic severity.

Pregnant women who reside in urban settings had 1.54 times better preventive practice for COVID-19 compared to their counterparts. This might be due to urban residents' pregnant women may have better access to information, being more educated, and can search for COVID-19 prevention methods. Studies in Guraghe, Wollega, low resource African settings, and Indian [21, 23, 25, 30] supported this evidence.

Regarding occupation, pregnant women who were civil servants, merchants, and employed in private sector were 1.81, 1.86, and 1.97 times more likely to practice COVID 19 prevention measures compared to housewives, respectively. This might be pregnant women who were housewife do not know what preventive measures are taken to avert the spread of COVID 19.

Those pregnant women with medical problems were 1.69 times more like to practice the prevention of COVID-19 When compared to their counterparts. The reason could be that pregnant women with medical problems may receive special attention and attempt to implement preventive measures against the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pregnant women with adequate knowledge of COVID-19 practiced 1.67 times better prevention than pregnant women with inadequate knowledge. The possible explanation for this might be knowledge is a prerequisite for applying preventive measures for COVID-19 pandemic. Studies in Ethiopia, South Africa, and India [20, 22, 28], supported this finding, respectively.

The study revealed that pregnant women with a favorable attitude were 1.74 times practicing good prevention of COVID-19 methods compared to their counterparts. The reason might be that when pregnant women have a good feeling about COVID-19 prevention, they are more likely to implement the techniques of the global infection prevention strategies.

This study was used primary data as a source of information to get a reliable data. The study was covered majority of the public health facilities in the zone. The nature of the design did not show the cause effect relationship of the factors. Due to the sensitivity of the COVID-19, the study had low response rate.

COVID-19 pandemic is the most intense and emotional experience of pregnant women's lives. Good knowledge and practice of pregnant women on COVID 19 contributes to filling the gap of preventive measures. The most determinant segment in the management of communicable disease is focusing on vulnerable targeted groups like pregnant women through evaluation of their knowledge and preventive practice.

The finding of this study showed that the knowledge and preventive practice against Corona virus pandemic among pregnant women attending ANC was 51.6% and 43.9% respectively. Intensified education and enforcement of the preventive measures will be required to interrupt the chain of transmission since the level of knowledge seems not to translate to the actual practice of preventing the pandemic. Continuous mass media program mobilization and health education should be considered for those who had medical problems, did not attend formal education, housewife, and rural resident women. Additional qualitative and observational studies that include pregnant women attending private health institutions might be advisable.

ANC: Antenatal Care

AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio

COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease of 2019

CI: Confidence Interval

COR: Crude Odd Ratio

SPSS: statistical package for social sciences

All the data included in the manuscript can be accessed from the corresponding author with reasonable query

The authors declare that we have no competing interests

There is no funding agency that supports this study

AA, MG and KA conceptualized, designed, and wrote the proposal, trained data collectors and supervisors, conducted analysis, wrote results, draft and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors are very grateful to express their gratitude to the study participants, data collectors, supervisors, Debre Markos University Health Sciences College, East Gojjam zone, and the regional health bureau.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Citation: Fetene M, (2023). Factors Determining Knowledge and Preventive Practice of COVID 19 Pandemic among Pregnant Women at Public Health Facilities: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. J Women's Health Care. 12(7):664.

Received: 22-Jun-2023, Manuscript No. 25435; Editor assigned: 26-Jun-2023, Pre QC No. 25435; Reviewed: 11-Jul-2023, QC No. 25435; Revised: 21-Jul-2023, Manuscript No. 25435; Published: 25-Jul-2023 , DOI: 10.35248/2167- 0420.23.12.665

Copyright: © 2023 Fetene M. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited