Anesthesia & Clinical Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-6148

ISSN: 2155-6148

Research Article - (2022)Volume 13, Issue 3

Background: Spinal anesthesia is an anesthesia technique suitable for cesarean section to avoid respiratory complications. However, the management of spinal anesthesia is very important because spinal anesthesia may fail and the patient may be exposed to pain and discomfort.

Objectives: To assess the type, management, and related factors of failure of spinal anesthesia at cesarean section.

Methods: Multicenter prospective cohort study was conducted at a public hospital in Addis Ababa on 794 mothers who met the criteria for cesarean section under spinal anesthesia. Data collection methods were adopted, including chart reviews and observations of spinal anesthesia procedures. The data collected was entered in Epi info version 7 and analyzed in SPSS version 20. Independent variables with dependent variables were analyzed using logistic regression. A p-value of 0.05 and it was considered a statistically significant test cutoff.

Results: Of 121 failed spinal anesthesia 35 were complete and 86 were partial failed spinal anesthesia from those complete failed spinal anesthesia were managed by repeating spinal and converting to general anesthesia and partial failed spinal anesthesia were managed by the supplementary drug. Experience of the anesthetist<1 (AOR=4.12, 95% CI, 2.47-6.90), patient position (AOR=14.43,95%CL, 2.65-78.61), number of attempt>1 (AOR=9.26, 95% CI, 5.69-15.01), bloody CSF (AOR=6.37, 95%CI, 2.90-13.96), BMI ≥ 30 kgm2 (AOR=2.03, 95%CI, 1.12-3.68) and dose of bupivacaine<10 mg (AOR=2.72, 95% CI, 1.33-5.53) were found to be statistically significant associated with failed spinal anesthesia.

Conclusion: Experience of anesthetists (<1 year), obesity, bupivacaine dose<10mg, bloody appearance of CSF, number of attempts>1 were associated factors for failed spinal anesthesia in cesarean section. Our failed spinal management is not the same among hospitals and does not follow recommended failed spinal managements. Up-skilling of anesthesia professionals should be considered on identified associated factors of failed spinal anesthesia and managements of failed spinal anesthesia should be based on the recommended guidelines.

Failed spinal anesthesia; Cesarean section; Spinal anesthesia

With the rate of cesarean section increasing worldwide, spinal anesthesia is the anesthetic of choice for the procedure. Spinal anesthesia is performed by injecting a local anesthetic into the cerebrospinal fluid [1,2]. Failure of spinal anesthesia may be partial or complete. Complete failure is defined as the absence of sensory or motor blockade, and partial failure is defined as insufficient level, quality, or duration of drug action for that particular surgery [3,4]. If you are using bupivacaine; if anesthesia and pain relief is not achieved within 10 minutes after heavy bupivacaine administration or within 25 minutes after successful intrathecal isobaric bupivacaine administration, it is considered a spinal anesthesia failure and also inability to access the subarachnoid space during lumbar puncture was considered as a spinal failure to prevent pain during cesarean section, anesthesia up to T5 is required [5,6].

Block height estimates may vary depending on the relationship between the evaluator's experience and the patient's perception, as well as the estimated block height by touch, prick, or chill [7]. Achieving spinal anesthesia depends on the experience of the anesthesiologist. Many studies consider obesity as an independent predictor of FSA, but others disagree. Many other factors were also considered, such as blood present in the cerebrospinal fluid, emergency cesarean section, multiple trials, bupivacaine dose, duration of surgery, prior anesthesia, spinal needle type and size, and bupivacaine baricity. This is due to the heavy pressure of unsuccessful spinal anesthesia [7-11].

According to a report of 92 maternal deaths in South Africa between 2008 and 2010, 73 (79%) of patients died from spinal anesthesia, of these, 10 were associated with complications from general anesthesia performed when spinal anesthesia was insufficient for surgery. Lack of clinical experience and inadequate access are the leading causes of maternal mortality. This is because there are few options to approach failure [1]. Successful spinal anesthesia may be partial or complete and may require the use of various adjuvants or conversion to general anesthesia, which may have medical and legal implications. The most common cause of gynecological anesthesia lawsuits is discomfort during cesarean section with spinal anesthesia [2]. Many studies have linked spinal block failure with other factors in developed countries. Data on the management and co-factors of spinal anesthesia failure in our country are limited. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to evaluate the types and management of spinal anesthesia failure and the co-factors of spinal anesthesia failure.

Study area and design

Multicenter prospective cohort study was conducted at Addis Ababa city public hospital, Ethiopia from December 2018 to May 2019. Addis Ababa is the capital city of Ethiopia with a population of 3,475,952 according to the 2007 population census. The city has 40 hospitals (12 public and 28 private), 29 health centers, 122 health stations, 37 health posts, and 382 private medium clinics [12]. In each hospital on average, there are two or more operating rooms to provide surgical services for emergency as well elective procedures. The methodology in this study followed the international guidelines for Strengthening The Reporting of Cohort Studies in Surgery (STROCSS) 2019 statement [13].

Source and study population

Source of population: All mothers who underwent elective and emergency cesarean section at Addis Ababa public hospitals.

Study population: Mothers who underwent elective and emergency cesarean section under spinal anesthesia fulfilled the inclusive criteria at Addis Ababa public hospitals during the study period.

Inclusion: All ASA I and ASA II mothers who underwent elective or emergency cesarean section under spinal anesthesia were included in the study.

Exclusive criteria: Mothers who had Combined Spinal-Epidural (CSE) for labor analgesia and mothers who developed intraoperative high or total spinal anesthesia.

Variables

Dependent variable: Failed Spinal Anesthesia (yes or no)

Independent variable

• Socio-demographic characteristics: Age, weight, height, and BMI.

• Obstetric related factor: Gestational age, classification of cesarean section.

• Anesthesia-related factors: Previous anesthesia history, ASA status, anesthetist experience, patient position, spinal needle type and size of spinal needle, lumbar puncture approach and numbers of attempts, the appearance of CSF, dose, and baricity of bupivacaine, adjuvant drug, and level of lumbar puncture.

• Surgical related factors: Duration of surgery and blood loss.

Operational definition

• Complete failed spinal anesthesia: No somatosensory block at all.

• Partial failed spinal anesthesia: There is a partial block but needs supplemental analgesia to complete the surgery.

• Experience having <1 year consider all undergraduate students and graduates having less than or equal to one year.

• Experience having >1 year considers all postgraduate student and professionals who has been providing clinical service for >1 year.

Sample size and sampling techniques

Sample size calculation: Using a single population proportion formula with the proportion of failed spinal anesthesia [9.1%], 95% confidence level and margin of error α=5%. We found a sample size of =794

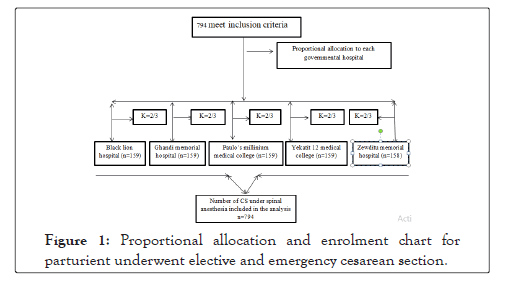

Sampling technique: Five public hospitals were randomly selected out of twelve by lottery method and then the sample size was proportionally allocated over the selected hospitals. We observed 1225 mothers from logbooks who get operated on for cesarean delivery during the past three and half months at selected Addis Ababa public hospitals. Then study unit was determined from 1225 mothers estimated to undergo emergency and elective cesarean section under spinal anesthesia in five public hospitals during the study period, 794 participants were recruited with the probability of about 65% by considering the consecutive emergency or elective cesarean section. Of all 794 participants were selected by systemic random sampling The first parturient was selected randomly and used as exclusion criteria then data collection were made on 2 mothers for every 3 mothers who underwent emergency and elective cesarean section until the required sample size is reached (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Proportional allocation and enrolment chart for parturient underwent elective and emergency cesarean section.

Data collection procedures

Data were collected through patient interviews, medical card reviewing, and observing spinal anesthesia procedures. We collect data on five major areas. The first data were about participants` demographic information (age, weight, height, and BMI); second–Obstetric related data (indication for Caesarean section, classification of surgery (elective or emergency), gestational age, and number of previous Caesarean sections were recorded); thirdly anesthetic related data (the previous history of anesthesia, ASA status, position in which the spinal was performed, intervertebral space used, type and dose of bupivacaine injected, sensory block height determined by loss of cold sensation ion, motor grading, need for intravenous supplemental analgesia (e.g. ketamine, fentanyl, and pethidine), need for conversion to general anesthesia or repeating spinal anesthesia and the status of the anesthetists and experience who performed the spinal block); and fourthly surgical related data (Duration of surgery, blood loss, and status of the surgeon).

Data quality control

To ensure data reliability and validity, questionnaires were pre- tested at 5% of the sample size before actual data collection. Learning orientation regarding the purpose and relevance of the study was provided by the principal observer. All elements of the survey tool and the entire data collection process were left to the data collectors and supervisors. Regular monitoring and follow- up were performed during data collection. Each questionnaire was reviewed daily by the supervisor and then double-checked for completeness and consistency by the study director. Incomplete data was not entered in the database prepared by Epi Info. Data cleansing and cross-validation of missing data were performed before analysis in Excel and SPSS.

Data analysis and interpretation

Data were coded and entered in Epi info version 7 and exported to SPSS version 20. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20 windows and all independent variables with dependent variables were analyzed using binary logistic regression. Odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and p-values were calculated to identify relevant factors and determine the degree of association. For multivariate logistic regression analysis, variables with a p-value less than 0.2 in bivariate logistic analysis, p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The data were obtained from a total of 794 participants with the mean age 28.39 ± 5.873 and BMI 24.56 ± 3.22. Of the total participants 225 (28.3%) were emergency and 569 (71.7%) were elective cesarean section (Table 1).

| Variables | Categories’ | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15-24 | 244 | 30.7 |

| 25-34 | 410 | 51.6 | |

| 35-44 | 140 | 17.6 | |

| BMI |

<18.5 | 59 | 0.6 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 489 | 61.6 | |

| 25-34.9 | 218 | 27.5 | |

| 35-39.9 | 56 | 7.1 | |

| ≥ 40 | 3 | 0.4 | |

| Classification | Emergency | 225 | 28.3 |

| Elective | 569 | 71.7 | |

| Duration of surgery | <45 min | 67 | 8.4 |

| 45-60 min | 19 | 2.4 | |

| >60 min | 72 | 9.1 | |

| Blood loss | 0.5-1 litre | 72 | 9.1 |

| >1 litre | 722 | 90.9 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic, obstetric, and surgical characteristics of mothers who underwent emergency and elective cesarean section.

Anesthetic-related characteristics of 794 mothers underwent emergency and elective cesarean section

About 84.5% of the participants were classified as ASA-I and only 33.8% of the participants had had previous experience of spinal anesthesia. Almost all (98.9%) spinal anesthesia was performed in a sitting position and 58.7% of it was performed by an anesthetist who had more than a year of experience. Only 10% of participants received <10 mg while the rest received 10–15 mg of bupivacaine. The dermatome block level was optimally achieved by 67.3% of the participants. In the majority (60.3%) of participants’ spinal anesthesia injection was succeeded in the first attempt though it has been repeated two times in 19.4%, three times in 9.7%, and more in 10.6% parturient (Table 2).

| Variables | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| History of SA ASA status | Yes | 268 33.8 |

| No ASA I ASAII |

526 76.2 679 84.5 115 14.5 |

|

| Experience of anesthetist | <1 year | 328 41.3 |

| ≥ 1 year | 466 58.7 | |

| Patient position | Sitting | 785 98.9 |

| Lateral | 9 1.1 | |

| Baricity bupivacaine | Isobaric | 748 94.2 |

| Hyperbaric | 46 5.8 | |

| Dose of bupivacaine | <10 mg | 84 10.6 |

| ≥ 10 mg | 710 89.4 | |

| Appearance of CSF | Clear | 751 94.6 |

| Bloody | 43 5.4 | |

| Spinal needle | ≥ 24 gauge | 175 22 |

| <23 gauge | 619 78 | |

| Adjuvant | Yes | 121 15.2 |

| No | 673 84.8 | |

| Intervertebral space of injection | L2-L3 L3-L4 L4-L5 |

7 0.9 758 95.5 29 3.7 |

Table 2: Prevalence and effects of Coronavirus (COVID-19) in pregnant women in Haiti.

Type, management and associated factors of failed spinal anesthesia

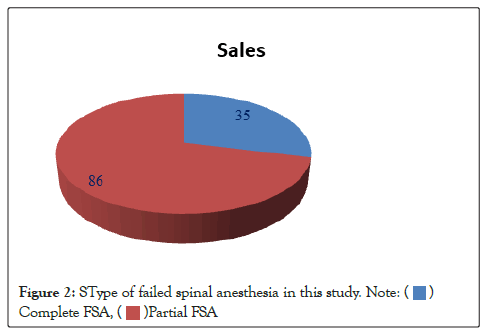

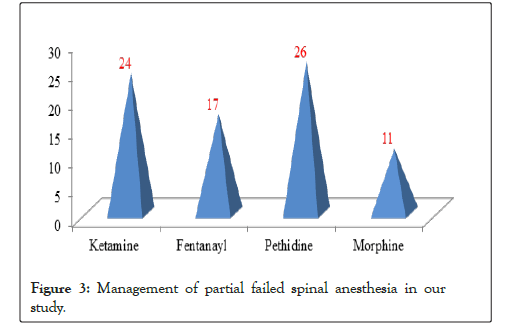

Of 121 failed spinal anesthesia in this study. 35 completely failed spinal anesthesia, and 86 partially failed spinal anesthesia. Of 35 complete failed spinal anesthesia. 6 were managed by way of repeating spinal anesthesia and the remaining 29 were converted into general anesthesia. Partial failed spinal anesthesia in this study was managed by ketamine 24, fentanyl 17, and pethidine 26 and morphine 11 (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: SType of failed spinal anesthesia in this study.

Figure 3: Management of partial failed spinal anesthesia in our study.

In this study we found a statistically significant association of failed spinal anesthesia with; BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (AOR=2.03, 95%CI, 1.12- 3.68), less experienced anesthetist (<1 year) (AOR=4.60, 95%CI, 2.80-7.56), lateral patient position during injection (AOR=14.43, 95%CI, 2.65-78.61), number of attempts (AOR; 9.26, 95% CI; 5.69- 15.01), the bloody appearance of CSF (AOR=6.37, 95%CI, 2.90- 13.96), utilization of anesthetics without adjuvants (AOR=2.72, 95%CI, 1.33-5.53) and dose of bupivacaine (AOR=2.37; 95%CI, 1.20-4.68); during cesarean section (Table 3).

| Variables |

Failed-spinal anesthesia | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | |||||

| BMI (Kg/m2) | <30 | 92 (11.6%) | 579 (73%) | 1 | 1 | 0.02 |

| ≥ 30 | 29 (3.7%) | 94 (11.8%) | 1.94 (1.21-3.11) | 2.03 (1.12-3.68) | ||

| SA history |

No | 90 (11.3%) | 436 (55%) | 1 | 1 | 0.224 |

| Yes | 31 (3.9%) | 237 (29.8%) | 0.65 (0.41-0.98) | 0.72 (0.42-1.22) | ||

| Experience of anesthetist | ≥ 1 year | 35 (4.4%) | 431 (54.2%) | 1 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| <1 year | 86 (10.8%) | 242 (30.5%) | 4.38 (2.87-6.68) | 4.60 (2.80-7.56) | ||

| Patient position | Setting | 115 (14.5%) | 670 (84.4%) | 1 | 1 | 0.002 |

| Lateral | 6 (0.76%) | 3 (0.38%) | 11.65 (2.87-47.25) | 14.43 (2.65-78.61) | ||

| Appearance of CSF | Clear | 99 (12,5%) | 652 (82.1%) | 1 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Bloody | 22 (2.8%) | 21 (2,6%) | 6.90 (3.69-13.00) | 6.37 (2.90-13.96) | ||

| Numbers of attempt | 1 | 50 (6.3%) | 583 (73.4%) | 1 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| ≥ 1 | 71 (8.9%) | 90 (11.3%) | 9.20 (6.02-14.06) | 9.26 (5.69-15.06) | ||

| Baricity of bupivacaine | Isobaric | 110 (13.9%) | 638 (80.4%) | 1 | 1 | 0.66 |

| Hyperbaric | 11 (1.4%) | 35 (4.4%) | 1.81 (1.11-3.70) | 0.967 (0.40-2.32) | ||

| Dose of bupivacaine in mg | ≥ 10 | 102 (12.8%) | 608 (76.6%) | 1 | 1 | 0.013 |

| <10 | 19 (2.4%) | 65 (8.2%) | 1.74 (1.00-3.03) | 2.37 (1.20-4.68) | ||

| Adjuvant | Yes | 17 (2.14%) | 160 (20%) | 1 | 1 | 0.006 |

| No | 104 (13%) | 513 (64.6%) | 1,91 (1.11-3.28) | 2.72 (1.33-5.53) | ||

Where, 1:Reference Group; COR : Crude Odd Ratio; AOR: Adjusted Odd Ratio; CI :Confidence Interval; n :Number; % :Percentage

Table 3: Factors associated with failed spinal anesthesia in cesarean section.

Complete anesthesia without any discomfort was supposed to be achieved after spinal anesthesia for specific surgical procedures. Spinal anesthesia is called failed when anesthetic drugs fail to work completely to the required level after successfully injected into the subarachnoid spaces and or facing difficulty accessing subarachnoid space [5,7]. In our study, 80% of completely failed spinal anesthesia was converted into general anesthesia and the remaining was managed by repeated spinal anesthesia. The Royal College of Anesthetists recommended, in possession with best practice, the change rate from spinal anesthesia to a GA should be ˂1% for elective CS and ˂3% for non-elective CS. but in this study, the conversion rate is high and which might increases the morbidity and mortality of both mother and baby [2]. The partial failed spinal anesthesia was managed by supplementary drug. There is no failed spinal management algorithm in each hospital. Hence, follow different management modalities. Thus in our study management of failed spinal anesthesia was inconsistent with guidelines developed by NHS foundation trust [1].

On multivariable logistic regression analysis, we found mothers who were not taken adjuvant were greater than 2 times more likely to require intraoperative analgesia. Possible justification could be since adjuvant potentiates local anesthetic and decreases the intraoperative requirement of analgesia [7,10,12]. This study showed experience year of anesthetists (<1 year) was significantly associated with the occurrence of failed spinal anesthesia. Possible justification could be explained as a technical error like loss of injectate, misplace injection, solution selection error, inappropriate dose selection, incorrect positioning, and inappropriate needle insertion due to that spinal anesthesia became the unilateral or inadequate sensory height of spinal anesthesia [13,14].

We found mothers whose BMI ≥ 30 km2 were at higher odds of resulting in Failed Spinal Anesthesia (FSA), this finding was consistent with the study result of Alabi, et al. [15]. But it is inconsistent with the study of Rukewe [5]. The possible reason could be due to anatomical challenges of accessing the intervertebral space and skills of anesthetists performing spinal anesthesia the obscured landmark in mothers whose BMI ≥ 30 km2 makes the identification of the landmark for spinal anesthesia difficult to locate and it also affects the distribution of local anesthetic [15,16]. However, some studies did not report any difficulty in performing spinal anesthesia in obese pregnant women [14].

Bloody CSF appearance was associated with failed spinal anesthesia; which is consistent with Alabi A et al. study [15]. This might be due to incorrect placement of the spinal needle in the subarachnoid space; the appearance of clear CSF in the needle hub is an essential pre-requisite for spinal anesthesia although it did not guarantee success [18,19].

More than a one-time attempt of spinal needle insertion was found to be associated with failed spinal anesthesia; which was consistent with the study, by Rukewe, et al. multiple punctures were associated with failed spinal anesthesia [5]. However; intervertebral space placement was not found a significant association for failed spinal anesthesia unlike that of Rukewe, where L4-L5 intervertebral space was associated with failed spinal anesthesia [5]. The speed of onset, quality, and duration of spinal anesthesia is determined by the dose of the local anesthetic [20]. In this study, the result demonstrated mothers who were taken (<10 mg of bupivacaine) were associated with failed spinal anesthesia compared with mothers who were taken (≥ 10 mg of bupivacaine) which was inconsistent with the study done by Rukewe [5,21-25].

Experience of anesthetists (<1 year), obesity, bupivacaine dose <10mg, bloody appearance of CSF, number of attempts>1 were associated factors for failed spinal anesthesia in cesarean section. Our failed spinal management is not the same among hospitals and does not follow recommended failed spinal managements. Up-skilling of anesthesia professionals should be considered on identified associated factors of failed spinal anesthesia and managements of failed spinal anesthesia should be based on the recommended guidelines.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]`

Citation: Bekele Z (2022) Subjective Failed Spinal Anesthesia in Cesarean Section; Type, Management, and Associated Factors, in One of the Resource- Limited Settings in Ethiopia: Prospective Cohort Study. J Anesth Clin.Res. 13:1048.

Received: 14-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. JACR-22-16245; Editor assigned: 16-Mar-2022, Pre QC No. JACR-22-16245 (PQ); Reviewed: 30-Mar-2022, QC No. JACR-22-16245; Revised: 04-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. JACR-22-16245 (R); Published: 18-Apr-2022 , DOI: 10.35248/2155-6148.22.13.1048

Copyright: © unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.