Journal of Horticulture

Open Access

ISSN: 2376-0354

ISSN: 2376-0354

Review Article - (2024)Volume 11, Issue 2

As communities try to fill in the gaps for those who are hungry, have no food, or are food insecure during the month, many programs have been initiated. The food systems across the United States include many sources of food besides grocery stores. A person can purchase food from big box stores, gas stations, farmers markets, and small local grocery stores. Free food can be obtained from food pantries, school lunch programs funded by the US department of agriculture, church run meal programs and community run meals on wheels for seniors. The US Department of Agriculture also runs programs for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and Supplemental Food Assistance Programs (SNAP). In spite of this, there are still gaps in communities across the US. Research shows an estimated 11.1% of households in the United States experienced food insecurity during 2018. This is of concern because associated with food insecurity is decreased quality of diet, such as lower intake of nutrient-rich fruits and vegetables, and poorer health outcomes.

A community level action to increase access to fresh vegetables is through garden grow a row/plant a row for the hungry programs being implemented throughout the US and Canada. We report here the design and implementation of a pilot project, grow a row, in the Vermillion Community Garden (VCG) for a small community of population about 10,000. The primary goal achieved was in providing fresh produce for the food pantry serving the county with the secondary goals of engagement of the VCG gardeners in this community effort and sustainability of the grow a row program to address food insecurity in the community. The produce donated to the food pantry came from three dedicated plots and from VCG gardeners, delivered on a weekly basis throughout the 2016-2018 growing seasons, May to November. Over 300 pounds (lbs) or 138 kilograms (kg) of food was grown and donated to the food pantry the first year, increasing to over 400 lbs by the third year. This report can serve as a guide for community gardens in other communities to participate in improving access to healthy foods.

Hunger; Food pantry; Community gardens; Food insecurity

Grow a Row, also known as plant a row for the hungry, is an effort gaining momentum across the United States (US) and Canada (see “further resources” for websites). As a way to address hunger in their communities, people volunteer to grow a little extra produce in either personal or community garden plots for donation to public food banks and food pantries.

This is important as a report from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) economic research service estimates that 11.1 percent of households in the United States experienced some level of food insecurity in 2018. Those most vulnerable to food insecurity are single women with children, the elderly, homeless, unemployed, agriculture workers, and minority populations.

As defined by the USDA, food insecurity refers to a lack of access, at times, to enough food for an active, healthy life for all household members and limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate foods due to lack of money or other resources. Negative impacts associated with food insecurity are decreased quality of diet, such as lower intake of nutrient-rich fruits and vegetables, and higher prevalence of chronic diseases and risk factors for these diseases [1,2].

In one state in the US (South Dakota) approximately 18% of children live in poverty and 23% of parents do not have secure employment to feed their children. Thirty percent of children live in single parent families and individuals or families with only one minimum wage job can earn about $17,680 (US dollars) per year. At this income level and below there is greater food insecurity. Further, food insecurity and hunger remain persistent public health problems despite government and community programs designed to address these issues [3].

In our community of 10,000 people, the number of families served each month by the food pantry ranged from 152 to 227 in 2016, on average about 600 individuals per month including children. While US federal nutrition assistance programs such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Special supplemental nutrition assistance for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) provide food assistance for those who are eligible, many people also need to turn to non-profit community organizations to fill the gaps. Moreover, Berner, Ozer, and Paynter found that the working poor as well as the unemployed visit food pantries and, of these, only 40 percent of food pantry clients are receiving SNAP government nutrition assistance. Today, communities reach out with a combination of public and private programs that include community gardens.

Relating to potential impacts of Grow A Row projects, objectives of the US healthy people 2020 goals included reducing household food insecurity (NWS-13) and increasing consumption of fruit and vegetables for individuals age two and up (NWS-14, 15) in part to protect against preventable chronic disease. Vitamins, minerals and fiber are important key nutrients lacking in the diets of many Americans and low-income individuals and families can be at risk for poor nutrition. Furthermore, lower intake of fresh fruits and vegetables is linked with increased risk for chronic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, and heart disease.

Interventions aimed at improving access to healthy foods showed that participants favored whole fruits and vegetables suggesting that access and availability may be limiting factors [4]. For this project, of concern are barriers to consumption of more fruits and vegetables for those living in rural, poor, and low population areas. One study reported that women in rural areas identify home and community gardens, free food pantries, and public transportation as necessary to increase access to healthy food for the poor. Insufficient local sources, distances to travel, and high food prices were listed as barriers to food access.

Many food pantries depend on donated foods and one of the challenges is in obtaining enough fresh fruits and vegetables for clients. One way to make more fresh fruit and vegetables that are locally grown available to food pantry recipients is to connect local community gardens and farmers markets with the food pantry. The purpose of this paper is to present the efforts and challenges to doing this at the local level through a grow a row program [5,6].

The following describes the approach used to connect a local community garden with the community food pantry to accomplish the primary goal of increasing access to fresh locally grown fruits and vegetables at the food pantry during the growing season. This first year was implemented as a pilot to build capacity and assess the approach. The Vermillion Community Garden (VCG) was established in 2005 and is registered as a non-profit organization. The vermillion food pantry is also a non-profit organization and serves residents of clay county, South Dakota, total population 14,011 [7].

In January 2016, the Coordinator for the vermillion community garden met with a representative from the vermillion food pantry to discuss planning and implementation of a pilot project, modeled on a national program called grow a row or plant a row. The program was discussed and adopted for the coming year. It was decided to have both designated rows and garden space for the food pantry as well as inviting gardeners in the community garden to “grow a row” for the food pantry. In February an application was submitted to the Hy-Vee one step community garden grant program to fund the project startup costs including seeds, plants, installation of new growing plots, mulch, baskets for harvesting/transporting, and a stipend for an intern to help with the harvest [8].

For the community garden, posters throughout the city advertise the plots at the end of March. A section was added to the written contract to invite gardeners to indicate if they were interested in a program to grow an extra row for the food pantry. This was followed by a May meeting, close to the last frost date for this geographic area, to sign up for specific crops and for organizers to distribute tomato and pepper plants, onion sets, and seeds to participating gardeners. Because the plots are small, the amount of space for the grow a row program was kept modest.

For example, four tomato plants or four peppers were given to a gardener. The type of produce selected to grow was coordinated with the Vermillion Food Pantry and included tomatoes, green onions, lettuce, spinach, peppers, radishes, sugar peas, cucumbers, green beans, summer squash, and herbs. The seeds and plants offered were intended to provide a variety in the five months of summer. Thirteen of the 30 VCG gardeners participated in the initial steps of the program [9].

In addition to recruitment of VCG gardeners, a new growing area was also set up as a designated food pantry garden. Two rows 2 by 20 feet were built as raised rows for lettuce, kale, spinach, onions, peppers, and cucumbers. Another 10 by 20 foot plot was designated for tomatoes and summer squash. Seeds were planted April 1st for lettuce, kale, and onions and covered by a row cover to protect them from freezing.

Such techniques were used to extend the growing season and to be able to have vegetables by the end of May in northern climates [10].

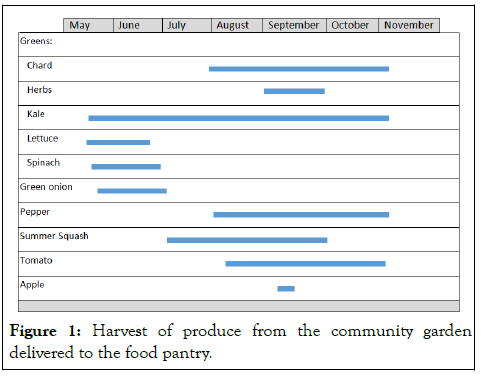

It was about seven weeks from planting to the first harvest. The first crop in May from the grow a row plantings was lettuce with later crops such as chard, peppers, and kale harvested into November. Figure 1 illustrates the timing for harvest of fruits and vegetables during the summer. The harvest from the grow a row program during this first year yielded 110 gallons of greens (including chard, herbs, kale, lettuce, and spinach) (88 lbs/40 kg), 50 summer squash (50 lbs/23 kg), 120 green onions (2 lbs/9 kg), 250 tomatoes (94 lbs/43 kg), 200 peppers (56 lbs/25 kg) and 50 apples from the VCG apple tree (10 lbs/4.5 kg). A total of 300 pounds (136 kilograms) of fresh produce was brought in to the food pantry from the grow a row program in the first year, followed by 300 and 421 pounds for 2017 and 2018, respectively [11,12].

A regular schedule was set up for harvesting and delivering produce to the food pantry. Once a week at the same time, harvested produce was brought to the food pantry using dedicated baskets that were purchased specifically to fit the shelves in the large coolers. Produce was packaged in family size units when appropriate for foods such as lettuce and kale.

The photo in Figure 1 shows one approach to encourage and teach pantry clients how to cook with some of the produce. In this example, kale was put into a gallon bag with garlic and green onion along with a recipe on how to saute it. Feedback was that the produce and the food kits were popular food items.

Figure 1: Harvest of produce from the community garden delivered to the food pantry.

Guidelines from the vermillion community garden grow a row pilot project

We started with an established community garden and expanded the gardening space for growing beds designated for this program. Some items in this list will need to begin earlier to either establish a new community garden and/or form a group of people to use their home gardens for the program. Coordinate early in the planning process with the food assistance organization to identify most needed food items and plan how to arrange schedule and method of delivery of garden produce.

Apply for funding if needed for infrastructure/capacity building and support for the gardeners by purchase seedlings and seeds for the program. For this pilot, part of the Hy Vee one step community grant awarded to the VCG was used to build new raised beds, purchase harvest baskets, harvest flags, plants and seeds for both the dedicated garden beds and for participating gardeners, and for an intern stipend. Funding sources may include community foundations and state, regional, or national organizations. Non-profit status may be required for grant application eligibility.

Engage community gardeners. For this pilot, the grow a row option was added to the annual contract sent out in March followed by an in person meeting in early May. Identify and address barriers to reaching, engaging, and maintaining participation in the program. Coordinate who will grow the preferred items agreed on with the food assistance program and keep in contact with gardeners. Keep an ongoing record of donated produce to assess how meeting objectives and to evaluate how well providing fresh produce over the growing season. Follow good gardening practices to maximize quality production: This project built new raised beds in an area with at least 8 hours of sun/day, used mulch to reduce weeds and maintain moisture, row covers to extend growing season in our zone and followed organic gardening practices.

This pilot project accomplished the main objectives to provide fresh locally grown produce to the community food pantry, engage community gardeners, and set up the infrastructure for maintaining and expanding the program, demonstrating that grow a row programs are feasible in small communities. The designated food pantry plots were successful at growing food for the pantry in the community garden. This program provided over 300 lbs/136 kg of fresh produce to the food pantry from mid-May to early November in its first year and has the capacity to increase the amount donated in upcoming years.

One of the challenges to this program was in communication and maintaining involvement from gardeners in the community garden in the grow a row program. Contributions were made by half of the initial thirteen members expressing commitment. A barrier identified is that it was more difficult to communicate what needed harvesting when as the season went on and coordinating with delivery to the food pantry. Email was used to communicate primarily which may not be the most effective mode for this organization. One change for the upcoming season will be for gardeners to mark the plants or rows dedicated to the grow a row program at the beginning of the growing season which will reduce the barriers of gardeners communicating to those harvesting. Another to extend harvest of early crops will be to plant greens such as lettuce again later in the summer for fall harvest.

The food pantry depends on donations that can vary in amount and type. Working together with the pantry, the Grow a Row program is able to provide a pre-selected variety of fresh produce that can enhance the availability of needed produce to households using the pantry.

A variety of spinach, kale, lettuce, green onions, tomatoes, peppers, and onions can add nutritional quality to a diet. These vegetables are low starch vegetables recommended for someone on a diabetic diet or combatting obesity and heart disease. A community garden based grow a row program is one way that fresh locally grown foods can be provided to support better nutrition for people utilizing food assistance programs. Below are guidelines in brief for other groups wishing to start a similar and sustainable program in their own communities.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Ahmed C (2024) Grow a Row: A Community Effort to Increase Vegetable and Fruit Access to Those with Food Insecurity by Linking a Community Garden with a Local Food Pantry. J Hortic. 11:363.

Received: 15-Nov-2019, Manuscript No. HORTICULTURE-24-2711; Editor assigned: 20-Nov-2019, Pre QC No. HORTICULTURE-24-2711 (PQ); Reviewed: 04-Dec-2019, QC No. HORTICULTURE-24-2711; Revised: 22-May-2024, Manuscript No. HORTICULTURE-24-2711 (R); Published: 19-Jun-2024 , DOI: 10.35248/2376-0354.24.11.363

Copyright: © 2024 Ahmed C. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.