Journal of Sleep Disorders & Therapy

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0277

ISSN: 2167-0277

Review Article - (2019)Volume 8, Issue 5

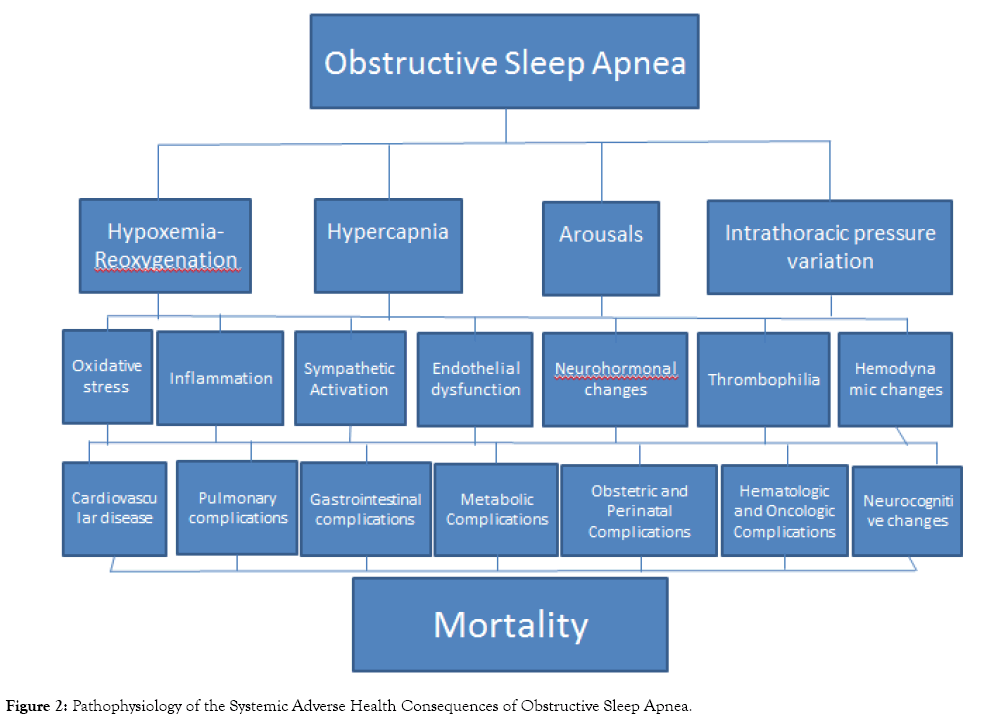

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), in addition to causing hypersomnolence and fatigue, adversely affects virtually every organ system, resulting in adverse neurologic, cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrine, gastrointestinal, obstetric, perinatal, perioperative, accident-related, and mortality-related health outcomes. Nocturnal respiratory dysfunction (i.e., hypoxemia-reoxygenation and hypercapnia), poor sleep quality (i.e., increased arousals, poor sleep efficiency, and altered sleep architecture), and intrathoracic pressure variations, in addition to shared comorbid risk factors, result in oxidative stress, inflammation, sympathetic activation, endothelial dysfunction, neurohormonal changes, thrombophilia, and hemodynamic changes, which are the pathophysiologic mechanisms for these adverse clinical outcomes.

Consequences; Complications; Health outcomes; Morbidity; Mortality

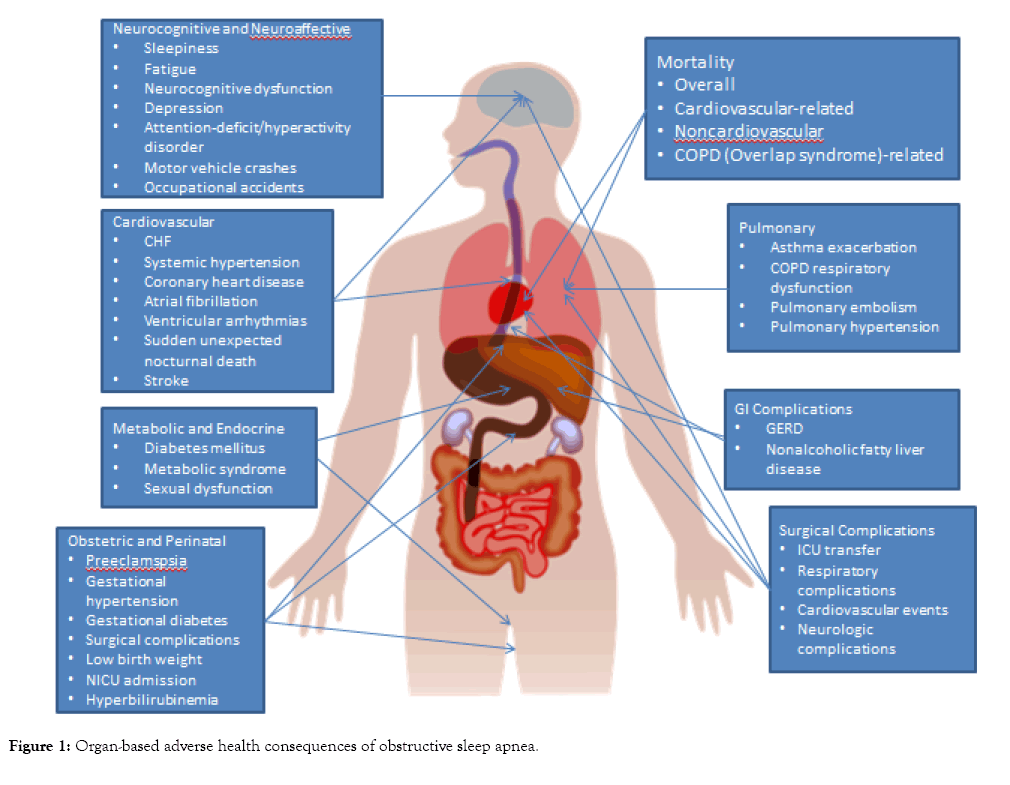

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is associated with a growing number of adverse health outcomes (Figure 1). This article is a descriptive narrative review of the current evidence and mechanisms behind the association between OSA and various adverse cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, respiratory, endocrine and metabolic, gastrointestinal, obstetric, perinatal, perioperative, accident-related, oncologic, and survival outcomes.

Figure 1: Organ-based adverse health consequences of obstructive sleep apnea.

The discussion of neurocognitive consequences of OSA merits its own literature review and will not be covered in this article. Since this review aims to establish general associations between OSA and health consequences, the articles selected for this review included all meta-analysis and randomized, controlled trials pertaining to these associations that have been cited in PubMed. Given the multisystem scope of this review, this solo author review will neither grade the quality of the studies cited nor discuss the impact of OSA therapies on these adverse health consequences.

The Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS) is the first nationwide, population-based study to employ home polysomnography (PSG) in order to investigate the relationship between SRBD and cardiovascular disease in community-dwelling, middle-aged adults in the United States [1]. The cross-sectional analysis of the SHHS revealed an apparent dose-response relationship between the severity of OSA based on the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) or the time spent with oxygen saturation below 90% (SpO2<90%) and the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, even after adjusting for known risk factors such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), systemic hypertension, and high-density lipoprotein [2]. Since the publication of this cross-sectional study, several meta-analyses have been published analyzing the relationship between OSA and cardiovascular disease (Table 1).

| Cardiovascular Outcomes | Strength of Association, Point Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) | References (Author, Year of Publication) | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Congestive heart failure | aOR=2.38 (1.22, 4.62) overall | [2] | Cross-sectional |

| aOR=1.19 (0.56, 2.53) for AHI=1.3-4.3/hr | |||

| aOR=1.96 (0.99, 3.90) for AHI=4.4 to < 10.9/hr | |||

| aOR=2.20 (1.11, 4.37) for AHI ≥ 11/hr | |||

| Systemic hypertension | OR=1.37 (1.03, 1.83) comparing highest (AHI ≥ 30/hr) vs. lowest (AHI <1.5/hr) categories | [3-5] | Cross-sectional Prospective cohort Meta-analysis |

| OR=1.41 (1.29, 1.89) comparing highest (≥ 12%) vs. lowest (0.05%) categories of percentage of sleep time below 90% oxygen saturation | |||

| aOR=1.51 (0.93-2.47) for AHI > 30/hr | |||

| OR=1.26 (1.17, 1.35) for mild OSA | |||

| OR=1.50 (1.27, 1.76) for moderate OSA | |||

| OR=1.47 (1.33, 1.64) for severe OSA | |||

| Resistant Hypertension | aOR 3.5 (0.8, 15.4) in non-CKD | [6] | Prospective cohort |

| aOR=1.2, (0.4, 3.7) in nondialysis CKD | |||

| aOR=7.1, (2.2, 23.2) in ESRD on dialysis | |||

| Coronary heart disease | aOR=1.27 (0.99, 1.62) | [2,7-9] | Cross-sectional |

| OR=1.56 (0.83, 2.91) | Meta-analysis | ||

| OR=1.92 (1.06, 3.4) in 5 male-predominant studies | Meta-analysis | ||

| RR= 1.37 (0.95-1.98) | Meta-analysis | ||

| RR=2.06 (1.13, 3.77) for recurrent ischemic heart disease | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | RR=2.48 (1.98, 3.10) | [8,16] |

Meta-analysis |

| RR=1.79 (1.47, 2.18) for severe OSA | |||

| Nonfatal cardiovascular events | OR=2.46 (1.80, 3.36) | [10] | Meta-analysis |

| Cardiovascular Events After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention | RR=1.59 (1.22, 2.06) | [11] | Meta-analysis |

| Subclinical cardiovascular disease | aOR range=1.036 – 2.21 for coronary artery calcium | [94] | Systematic review |

| Prevalent atrial fibrillation | aOR=4.02 (1.03, 15.74) | [95] | Cross-sectional |

| OR=2.15 (1.19, 3.89) in older men in the highest RDI quartile | [96] | Cross-sectional | |

| Incident atrial fibrillation | HR=2.18 (1.34, 3.54) | [12] | Retrospective cohort |

| Atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation | RR=1.25 (1.08, 1.45) | [97] | Meta-analysis |

| Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia | OR=3.40 (1.03, 11.20) | [95] | Cross-sectional |

| Complex ventricular ectopy | OR=1.74 (1.11, 2.74) | [95] | Cross-sectional |

| Ventricular arrhythmias between 12 am – 6 am in patient with cardioverter-defibrillator | OR=5.6 (2.0, 15.6) | [98] | Prospective cohort |

| Stroke | aOR=1.42 (1.13, 1.78) | [2,7-9,15,16] |

Cross-sectional |

| OR=2.24, (1.57, 3.19) | Meta-analysis | ||

| RR=2.02 (1.40, 2.90) | Meta-analysis | ||

| RR=2.15 (1.42, 3.24) for severe OSA | Meta-analysis | ||

| OR=1.94, (1.29, 2.92) | Meta-analysis | ||

| RR=2.15 (1.42, 3.24) in severe OSA | Meta-analysis |

Note: aOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; OR: Odds Ratio; AHI: Apnea Hypopnea Index; CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease; ESRD: End-Stage Renal Disease; RR: Relative Risk or Risk Ratio; HR: Hazard Ratio

Table 1: Strength of Association between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Outcomes.

Chronic heart failure

The SHHS study found that of all the cardiovascular comorbidities, self-reported chronic heart failure (CHF) had the strongest association with OSA [2]. When stratified based on OSA severity, the highest quartile of AHI category (>11/hr) had the strongest relationship with heart failure. There are, however, no prospective cohort studies comparing the incidence of CHF in OSA patients with controls.

Systemic hypertension

A cross-sectional analysis of the SHHS data found that participants with OSA (AHI ≥ 5/hr) or prolonged nocturnal hypoxemia (percentage of time spent with SpO2<90 % for at least 12% of the total sleep time) were more likely to have systemic hypertension than those with no OSA or with shorter duration of nocturnal hypoxemia, respectively [3]. However, a prospective cohort analysis of SHHS data did not find a significant increase in the incidence of hypertension when controlling for BMI after 5 years of follow-up of participants who were normotensive at baseline [4]. Nevertheless, a metaanalysis of 6 studies enrolling 20,637 participants still confirmed a statistically significantly elevated risk of systemic hypertension in OSA, regardless of severity [5].

OSA is also strongly linked with resistant hypertension in patients with renal impairment. The Sleep-SCORE study employed unattended home PSG and automated blood pressure (BP) monitoring on 88 non-dialysis dependent and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients and found that the severity of sleep apnea was associated with resistant hypertension (defined as having a BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg despite ≥ 3 antihypertensive medications) only in those with ESRD on dialysis but not in those without chronic kidney disease (CKD) or in those with CKD not on dialysis [6].

Coronary heart disease

The cross-sectional analysis of the SHHS did not find a significant increase in the prevalence of self-reported coronary heart disease (CHD) in OSA [2]. Subsequent meta-analyses on the relationship of OSA and CHD reported somewhat mixed results. The first 2 meta-analyses by Loke and Dong, respectively, focused only on prospective studies and similarly found no association between OSA and incident CHD occurring during follow-up [7,8]. The reasons behind the lack of association between OSA and incident CHD are unexplained but may include the selection of a low CHD-risk cohort, short duration of follow-up, intensive medical regimen for participants, or other unforeseen confounding factors. On the other hand, in subjects with baseline CHD at the start of the study, OSA appeared to heighten the risk of a recurrent coronary event. A meta-analysis of prospective studies that included only those with baseline CHD reported a doubling of the risk of a recurrent ischemic event [9]. Another meta-analysis also reported an increase in nonfatal cardiovascular events in patients with OSA [10]. The incidence of acute coronary events after percutaneous coronary intervention is also significantly increased [11]. A systematic review on noninvasive studies evaluating subclinical cardiovascular disease revealed that OSA is significantly associated with signs of atherosclerosis, including coronary artery calcification, carotid intima thickness, brachial artery flow-mediated dilatation, and pulse wave velocity.

Arrhythmias

Arrhythmias are perceived to occur more commonly in patients with OSA. A retrospective cohort study of adults with OSA found a statistically significant doubling of the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation (AF) after 4.7 years of follow-up, particularly in subjects younger than 65 years, even after adjusting for known cardiovascular risk factors [12]. Nocturnal oxygen desaturation was found to be a significant predictor of incident AF. Meanwhile, a systematic review of 22 studies by Raghuram and colleagues concluded that subjects with OSA were more likely to have ventricular ectopy and arrhythmias but was unable to estimate the strength of the association due to data heterogeneity [13].

Cerebrovascular disease

The prevalence of SRBD appears to be high in patients with cerebrovascular disease (CVD): 72% in stroke patients with an AHI>5 and 20% in those with AHI>20 [14]. The predominant type of SRBD was OSA, with only 7% having primarily central apnea [14]. Factors associated with SRBD in stroke were male gender, recurrent strokes, and an idiopathic etiology, but not event type (ischemic vs. hemorrhage), timing after stroke, or type of monitoring [14]. The cross-sectional analysis of the SHHS data also reported a strong association between stroke and OSA [2].

Conversely, 4 subsequent meta-analyses confirmed the higher incidence of stroke in OSA patients. Li and colleagues reported a doubling of the risk of incident fatal and non-fatal strokes in patients with OSA [15]. Loke et al. corroborated this association but reported that most studies primarily enrolled men [7]. Xie and colleagues confirmed that OSA patients with either a history of CVD or CHD had a significantly higher risk of stroke [9]. The risk of stroke appeared to be related to the severity of OSA, i.e., higher stroke risk in moderate-to-severe OSA but not in mild OSA [16].

Asthma

Asthmatic patients are more than twice as likely to have OSA, particularly in those with a higher BMI [17,18] (Table 2). Comorbid OSA can impair asthma control and increase the frequency of asthma exacerbations [19,20].

| Pulmonary Outcomes | Strength of Association, Point Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

References (Author, Year of Publication) |

Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma exacerbation | aOR=1.322 (1.148, 1.523) with AHI aOR=3.4 (1.2, 10.4) |

[19] [20] |

Case-control

Retrospective cohort |

| COPD exacerbation requiring hospitalization | RR=1.70 (1.21, 2.38) | [22] | Prospective cohort |

| Pulmonary embolism | aOR=3.7 (1.3, 10.5) | [27] | Prospective cohort |

| Recurrent pulmonary embolism | aHR=20.73 (1.71, 251.28) | [28] | Prospective cohort |

Note: aOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; AHI: Apnea-Hypopnea Index; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; RR: Relative Risk or Risk Ratio; aHR: Adjusted Hazard Ratio

Table 2: Strength of Association between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Pulmonary Outcomes.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

The prevalence of OSA in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) ranges anywhere from 10 to 66% depending on the population sample [21]. A prospective cohort study demonstrated that co-morbid OSA in COPD patients was associated with a significantly higher frequency of hospitalization due to severe exacerbation [22]. The combination of OSA and COPD (overlap syndrome) is associated with worse daytime and nighttime pulmonary function (i.e., hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and 6-minute walk distance) and polysomnographic findings [i.e., worse AHI and oxygen desaturation index (ODI), nocturnal hypoxemia, sleep efficiency, arousal index, and sleep architecture].

Pulmonary embolism

The prevalence of OSA appears to be significantly higher in patients who develop venous thromboembolism (VTE). A nested case-control study reported that patients diagnosed with deep venous thrombosis or acute pulmonary embolism had more than twice of the odds of having OSA, particularly in women, despite accounting for known risk factors for thrombophilia [23]. The majority (58.5%) of patients who survive an acute pulmonary embolism have OSA [24,25]. Moreover, those with high-risk pulmonary embolism were more likely to have moderate-to-severe OSA [24,25]. However, the transient increase in central venous pressure after an acute pulmonary embolism does not seem to worsen the severity of the AHI once the patients are clinically stable to undergo PSG [26].

OSA may well be considered as a thrombophilic condition. A case-control study of 209 patients found a higher prevalence of pulmonary embolism in patients with OSA [27]. The same investigators followed 120 patients with pulmonary embolism who had stopped their anticoagulation for 5 to 8 years and found a 20-fold increase in recurrent PE risk [28]. The severity of OSA based on the AHI and time spent with SpO2<90% were independent predictors of recurrent PE risk. The proposed mechanisms for this increased VTE risk include the heightened blood viscosity, clotting factors, tissue factor, platelet activity, and whole blood coagulability as well as the attenuated fibrinolysis in OSA [29].

Pulmonary hypertension

SRBD occurs quite often in patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH). One study found a 71% SRBD prevalence in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension, with 56% having OSA [30]. Patients who had SRBD tended to be older or sleepier. On the other hand, there are no controlled communitybased or clinical epidemiologic studies to accurately determine the frequency of PH in OSA patients. Nevertheless, descriptive studies indicate a disproportionately higher prevalence of PH in OSA patients. Published studies indicate a 17 to 67% prevalence of PH in OSA [31,32]. A study of 220 consecutive OSA patients who underwent right heart catheterization (RHC) determined a PH prevalence of 17% [33]. In this RHC study, PH occurrence was attributed to the presence of obstructive lung disease with hypoxemia and hypercapnia rather than OSA severity. A metaanalysis of studies utilizing echocardiographic evaluation of OSA patients demonstrated a higher prevalence of RV dilatation, hypertrophy, and dysfunction [34].

Diabetes mellitus

Although the cross-sectional analysis of the SHHS data found an association between diabetes mellitus (DM) and periodic breathing but not OSA [35], a prospective cohort analysis of both the SHHS and the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study databases reported a significantly higher incidence of DM in severe OSA patients after 13 years of follow-up (Table 3) [36]. A meta-analysis of 6 prospective cohort studies corroborated the elevated risk of incident DM in severe OSA [37].

| Metabolic Disease Outcomes | Strength of Association, Point Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

References (Author, Year of Publication) |

Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | RR=1.22 (0.91, 1.63) for mild OSA RR=1.63 (1.09, 2.45) for moderate-to-severe OSA HR=1.71 (1.08, 2.71) |

[37] [36] |

Meta-analysis

Prospective cohort |

| Diabetic kidney disease | OR=1.73 (1.13, 2.64) | [38] | Meta-analysis |

| Diabetic retinopathy | OR=0.91(0.87-0.95) with minimum oxygen saturation | [39] | Meta-analysis |

| Metabolic syndrome | OR=2.87 (2.41, 3.42) OR=2.56 (1.98, 3.31) aOR=1.97 (1.34, 2.88) |

[40]

[41] |

Meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies Meta-analysis of case-control studies Meta-analysis |

| Erectile dysfunction | RR = 1.82 (1.12, 2.97) | [45] | Meta-analysis |

| Female sexual dysfunction | RR=2.00 (1.29, 3.08) | [45] | Meta-analysis |

Note: RR: Relative Risk or Risk Ratio; HR: Hazard Ratio; OR: Odds Ratio; aOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio

Table 3: Strength of Association between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Endocrine and Metabolic Outcomes.

The risk of diabetic microvasculopathy seems to be similarly enhanced by OSA. A meta-analysis of longitudinal and crosssectional studies revealed a 73% higher risk of diabetic nephropathy with OSA [38]. Another meta-analysis performed by the same authors demonstrated a higher risk of diabetic retinopathy and maculopathy related to duration of nocturnal hypoxemia [39].

Metabolic syndrome

The metabolic syndrome consists of the triad of systemic hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia. Two metaanalyses reported at 2-to-3-fold increased risk of metabolic syndrome in OSA patients [40,41]. A meta-regression by Nadeem and colleagues identified the AHI as a significant independent predictor of low density lipoprotein and triglyceride levels [42]. In addition to impaired glucose tolerance and dyslipidemia, OSA is also associated with increased leptin levels related to the neck and waist circumference, nocturnal hypoxemia, glucose impairment, and C-reactive protein level independent of obesity [43,44].

Sexual dysfunction

A meta-analysis on the association of OSA and sexual dysfunction estimated that men and women with OSA had approximately double the risk of erectile dysfunction and female sexual dysfunction, respectively [45]. Steinke and colleagues systematically reviewed the role of OSA severity and medications in sexual dysfunction in both women and men with OSA and concluded that in addition to hormonal status, the duration of nocturnal hypoxemia was a significant determinant of sexual dysfunction in women while BMI and inflammatory markers were significant factors in men [46].

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

OSA is associated with an approximately 2-fold increased risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [47] and a 3-fold increased risk of nocturnal GERD (Table 4) [48]. The prevalence of nocturnal GERD seems to be related to the severity of OSA [49]. You and colleagues’ endoscopic study found a significant increase in nonerosive but not in erosive esophagitis in OSA patients [48]. Legget et al also demonstrated a trend towards Barrett’s esophagitis related to OSA severity [50].

| Gastrointestinal Disease Outcome | Strength of Association, Point Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) | References (Author, Year of Publication) |

Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| GERD | aOR=2.13 (1.17, 3.88) | [47] | Cross-sectional population-level analysis |

| Non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux Erosive gastroesophageal reflux |

aOR=1.82 (1.15, 2.90)

aOR=0.93 (0.56, 1.55) |

[48] | Cross-sectional |

| Nocturnal GERD | aOR=2.97 (1.19, 7.84) aOR=1.84(1.28, 2.63) for moderate OSA aOR=2.39 (1.71, 3.33) for severe OSA |

[48] [49] |

Cross-sectional Cross-sectional |

| Barrett’s esophagitis | aOR=1.2 (1.0, 1.3) per 10-unit increase in AHI | [50] | Cross-sectional |

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Fatty liver Inflammation Fibrosis |

OR=2.556 (1.184, 5.515 OR=1.800 (0.905, 3.579) OR=2.586 (1.289, 5.189) |

[55] | Meta-analysis |

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Histology Radiology Elevated AST or ALT NASH, any stage Fibrosis Advanced fibrosis |

OR=2.01 (1.36, 2.97) OR=2.34 (1.71, 3.18) OR=2.53 (1.93, 3.31) OR=2.37(1.59, 3.51) OR=2.16 (1.45, 3.20) OR=2.30 (1.21, 4.38). |

[56] | Meta-analysis |

Note: GERD: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease; aOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; OR: Odds Ratio; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; NASH: Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatosis

Table 4: Strength of Association between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Gastrointestinal Outcomes.

Conversely, patients with GERD symptoms were found to have significantly worse OSA-related PSG findings such as worse AHI, maximum apnea duration, minimum oxygen saturation, ODI, and sleep efficiency compared to those without [51]. Gastroesophageal reflux events appear to occur mostly after awakenings and arousals rather than after respiratory events [52,53]. Shepherd and colleagues investigated the mechanism behind GERD in OSA patients utilizing high-resolution esophageal manometry, 24-hr esophageal pH-impedance monitoring, and in-laboratory PSG and identified obesity to be the mediator of reflux events in OSA [54].

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

OSA is similarly associated with a 2-fold risk of non-alcoholic steatohepatosis, steatohepatitis, and hepatic fibrosis whether diagnosed histologically, chemically, or radiographically [55,56]. The increased prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in OSA patients is not surprising given the shared risk factors (e.g., obesity) and comorbidities (e.g., DM, metabolic syndrome, etc.) between these conditions.

Pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders Pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders such as pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension, and eclampsia occur more frequently in gravid women with OSA. A relatively recent systematic review/quantitative analysis, a meta-analysis, and a national cohort study all corroborated a doubling of the risk of preeclampsia in pregnant women with OSA (Table 5) [57-59].

| Obstetric Outcomes | Strength of Association, Point Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

References (Author, Year of Publication) |

Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preeclampsia | OR=2.19 (1.71, 2.80)

RR=1.96 (1.34, 2.86) aOR=2.22 (1.94, 2.54) |

[57]

[58] [59] |

Systematic review and quantitative analysis Meta-analysis Retrospective national cohort |

| Gestational hypertension | OR=2.38 (1.63, 3.47)

RR=1.40 (0.62, 3.19) aOR=1.67 (1.42, 1.97) |

[57]

[58] [59] |

Systematic review and quantitative analysis Meta-analysis Retrospective national cohort |

| Eclampsia | aOR=2.95 (1.08, 8.02) | [59] | Retrospective national cohort |

| Gestational diabetes | OR=1.78 (1.29, 2.46)

aOR=1.52 (1.34, 1.72) |

[57]

[59] |

Systematic review and quantitative analysis Retrospective national cohort |

| Pulmonary edema | aOR=5.06 (2.29, 11.1) | [59] | Retrospective national cohort |

| Congestive heart failure | aOR=3.63 (2.33, 5.66) | [59] | Retrospective national cohort |

| Cardiomyopathy | aOR=3.59 (2.31, 5.58) | [59] | Retrospective national cohort |

| Pulmonary embolism and infarction | aOR=5.25 (0.64, 42.9) | [59] | Retrospective national cohort |

| Stroke | aOR=3.12 (0.41, 23.9) | [59] | Retrospective national cohort |

| Caesarian delivery | aOR=1.53 (0.79, 2.96) for BMI < 30 aOR=3.48 (0.90, 13.37) for BMI ≥ 30 aOR=3.04 (1.14–8.1) RR=1.87 (1.52, 2.29) |

[63]

[64] [58] |

Prospective cohort

Prospective cohort Meta-analysis |

| Wound complications |

aOR=3.44 (0.7–16.93) aOR=1.77 (1.24, 2.54) |

[64] [59] |

Prospective cohort Retrospective national cohort |

| Hysterectomy | aOR=2.26 (1.29, 3.98) | [59] | Retrospective national cohort |

| Transfusion | aOR=0.81 (0.11, 5.85) | [59] | Retrospective national cohort |

| Length of Stay | aOR=1.18 (1.05, 1.32) | [59] | Retrospective national cohort |

| Maternal ICU admission | aOR=2.74 (2.36, 3.18) | [59] | Retrospective national cohort |

Note: OR: Odds Ratio; RR: Relative Risk or Risk Ratio; aOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; BMI: Body Mass Index; ICU: Intensive Care Unit

Table 5: Strength of Association between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Obstetric Outcomes.

Moreover, 2 of the 3 studies found a statistically significant association between OSA and gestational hypertension. The national cohort study by Bourjeilly et al reported a 3-fold increase in the incidence of eclampsia in pregnant women with OSA [59].

Gestational diabetes

Based on a systematic review and a national cohort study, the likelihood of developing gestational diabetes is 52 to 78% higher in pregnant women with OSA [57,59]. In a study of the interactions between pregnancy, OSA, and gestational diabetes, Reutrakul and colleagues determined that arousal index and ODI were significant independent predictors of hyperglycemia [60]. Purported mechanisms behind gestational diabetes in OSA patients include maternal sleep disruption, intermittent hypoxemia, oxidative stress, inflammation, catecholaminergic activation, peripheral vasoconstriction, and endothelial dysfunction. The severity of OSA appear to influence the degree of impairment of glucose tolerance. An immunologic assay on 23 participants with gestational diabetes revealed positive correlations between the AHI and serum levels interleukin 6, Interleukin 8, and tumor necrosis factor-α [61]. A crosssectional study of pregnant women with diet-controlled gestational diabetes who underwent a meal-tolerance test revealed that the degree of oxygen desaturation correlated with fasting glucose, insulin resistance, and β-cell function [62].

Maternal cardiovascular and pulmonary complications

A national cohort study of 1,577,632 gravidas in the United States reported a significantly higher incidence of maternal cardiovascular events such as pulmonary edema, CHF, and cardiomyopathy in pregnant women with OSA [59]. In contrast, although there was a 5-fold increase in the odds of pulmonary embolism or infarction in pregnant women with OSA in the same study, it was not found to be statistically significant [59]. The risk of peripartal stroke was also not elevated [59].

Maternal surgical complications

While an earlier small prospective cohort study did not find a difference in the need for caesarian delivery when using the Berlin Questionnaire to screen for OSA [63], a subsequent prospective study [64] and a meta-analysis of cohort studies [58] both reported a significantly greater need for caesarian delivery in pregnant women with OSA. There are 2 studies on wound complications after delivery with conflicting results, with a prospective cohort study [64] showing no significant increase while a large retrospective national cohort study showing a significant increase [59]. The same national cohort study found a significantly increased likelihood of maternal hysterectomy and ICU admission and a longer length of stay but no difference in blood transfusion requirement [59].

Impaired fetal growth

Studies on the effect of OSA on fetal growth have conflicting results. A prospective cohort study of 26 high- and 15 low-OSA risk pregnant women reported that the initially statistically significant crude association between maternal OSA and impaired fetal growth became insignificant after adjusting for BMI (Table 6) [65]. In contrast, a meta-analysis of 24 studies did find a significant association between maternal OSA and impaired fetal growth [57]. However, a recent national cohort study of more than 1.5 million gravidas also did not find any significant association between maternal OSA and fetal growth [59].

| Perinatal Outcomes | Strength of Association, Point Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

References (Author, Year of Publication) |

Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impaired fetal growth | aOR=5.3 (0.93, 30.34) OR=1.44 (1.22, 1.71) aOR=1.05 (0.84, 1.31) |

[65]

[57] [59] |

Prospective observational Systematic review and quantitative analysis Retrospective national cohort |

| Preterm birth: | aOR=0.63 (0.18, 2.24) for < 37 weeks aOR=0.94 (0.10, 8.92) for < 32 weeks OR=1.98 (1.59, 2.48) RR=1.90 (1.24, 2.91) |

[64]

[57] [58] |

Prospective cohort Systematic review and quantitative analysis Meta-analysis |

| Small for gestational age < 10th percentile | OR=2.56 (0.56, 11.68) for BMI < 30 OR=0.83 (0.04, 19.4) for BMI ≥ 30 |

[63] | Prospective cohort |

| Low birth weight | OR=1.75 (1.33, 2.32) | [57] | Systematic review and quantitative analysis |

| Stillbirth | aOR=1.17 (0.79, 1.73) | [99] | Retrospective national cohort |

| NICU admission | aOR=3.39 (1.23, 9.32) OR=2.43 (1.61, 3.68) RR=2.65 (1.68, 3.76) |

[64]

[57] [58] |

Prospective cohort

Systematic review and quantitative analysis Meta-analysis |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | aOR=3.63 (1.35–9.76) | [64] | Prospective cohort |

| Respiratory morbidity | aOR=1.56 (0.5–4.59) | [64] | Prospective cohort |

Note: aOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; OR: Odds Ratio; BMI: Body Mass Index; NICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; RR: Relative Risk or Risk Ratio

Table 6: Strength of Association between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Perinatal Outcomes.

Preterm birth

A prospective cohort study of 175 obese pregnant women did not find a significant increase in preterm birth in neonates of women with OSA [64]. In contrast, two subsequent metaanalyses studies reported a significant doubling of the risk of preterm birth in neonates of pregnant women with OSA [57,58].

Small for gestational age/low birthweight

Although a prospective cohort study of Korean pregnant women did not find a significant increase in the incidence of low birthweight in neonates of mothers at risk for OSA based on the Berlin Questionnaire [63], a subsequent meta-analysis of 24 studies reported a 75% increase in likelihood of low birthweight neonates in mothers with OSA [57].

Stillbirth

The one large national cohort study that investigated the risk of stillbirth in gravida women with OSA did not find it increased [59].

NICU admission

Three studies (1 prospective cohort study and 2 quantitative/ meta analyses) are unanimous in endorsing a 2-to-3-fold significant increase in the risk of ICU admission in newborns of mothers with OSA [57,58,64]. The prospective cohort study also found a significantly higher likelihood of hyperbilirubinemia but not respiratory morbidity in neonates of women with OSA [64].

Several meta-analyses as well as a retrospective nationwide cohort analysis attested to the negative effects of OSA on the majority of perioperative outcomes including ICU transfer, respiratory complications (i.e. post-operative hypoxemia, acute respiratory failure, emergent intubation, and need for CPAP or noninvasive ventilation), major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events, AF, and neurologic complications (Table 7) [66-71]. OSA did not prolong hospital length of stay, however [71]. A qualitative systematic review published by the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine Task Force on Preoperative Preparation of Patients with Sleep-Disordered Breathing in 2016 concluded that majority of the studies reported a higher risk of pulmonary and combined complications [72].

| Perioperative Outcomes | Strength of Association, Point Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

References (Author, Year of Publication) |

Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perioperative complications | OR=3.93 (1.85, 7.77) | [71] | Meta-analysis |

| ICU transfer |

OR=2.81 (1.46, 5.43) OR=2.97 (1.90, 4.64) OR=2.46 (1.29, 4.68) |

[66] [68] [69] |

Meta-analysis Meta-analysis Meta-analysis |

| Postoperative hypoxemia | OR=2.27 (1.20, 4.26) OR=3.06 (2.35, 3.97) |

[66] [68] |

Meta-analysis Meta-analysis |

| Respiratory complications | OR=2.77 (1.73, 4.43) | [68] | Meta-analysis |

| Acute respiratory failure | OR=2.43 (1.34, 4.39) OR=2.42 (1.53, 3.84) |

[66] [69] |

Meta-analysis |

| Postoperative tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation | OR=2.67 (1.0, 6.89) | [71] | Meta-analysis |

| MACCE | OR=2.4 (1.38, 4.2) | [71] | Meta-analysis |

| Cardiac events | OR=2.07 (1.23, 3.50) OR=1.63, (1.16, 2.29) OR=1.76 (1.16, 2.67) |

[66] [69] [68] |

Meta-analysis Meta-analysis Meta-analysis |

| New postoperative atrial fibrillation | OR=1.94 (1.13, 3.33) | [71] | Meta-analysis |

| Atrial fibrillation after CABG | aOR=2.38 (1.57, 3.62) | [70] | Meta-analysis |

| Hospital length of stay | Mean difference=+2.01 (0.77, 3.24) days | [71] | Meta-analysis |

| Neurologic complications | OR=2.65, (1.43, 4.92) | [68] | Meta-analysis |

Note: OR: Odds Ratio; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; MACCE: Major Adverse Cardiac or Cerebrovascular Events; aOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; CABG: Coronary Artery Bypass Graft

Table 7: Strength of Association between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Perioperative Outcomes.

OSA doubles the risk of motor vehicle crashes [73] and occupational accidents (Table 8) [74]. A meta-analysis identified BMI, AHI, nocturnal hypoxemia, and likely diurnal hypersomnolence as predictors of the motor vehicle crashes [73]. Furthermore, another meta-analysis determined that occupational driving was associated with a greater accident risk among workplace activities [74]. The heightened risk of motor vehicle crashes may be attributed to excessive daytime sleepiness, poor vigilance, and inattention resulting from OSA-related neurcognitive dysfunction.

| Type of Accident | Strength of Association, Point Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

References (Author, Year of Publication) |

Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motor vehicle crashes | OR=2.427 (1.205, 4.890) | [73] | Systematic review |

| Occupational accidents | OR=2.18 (1.53, 3.10) | [74] | Meta-analysis |

Note: OR: Odds Ratio

Table 8: Strength of Association between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Accident-Related Outcomes.

There are two meta-analyses published 2 years apart on the association between cancer incidence and OSA with contradictory results (Table 9) [75,76]. Further studies are needed to arbitrate these conflicting results of the effect of OSA and mortality and to elucidate the mechanisms by which OSA influences cancer incidence. Meanwhile, a meta-analysis by Zhang et al did not report an association between OSA and cancer mortality [76].

| Cancer Outcomes | Strength of Association, Point Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

References (Author, Year of Publication) |

Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer incidence | aRR=1.40 (1.01, 1.95) aHR=0.91 (0.74, 1.13) for mild OSA aHR=1.07 (0.86,1.33) for moderate OSA aHR=1.03 (0.85, 1.26) for severe OSA |

[75] [76] |

Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis |

| Cancer mortality | aHR=0.79 (0.46, 1.34) for mild OSA aHR=1.92 (0.63, 5.88) for moderate OSA aHR=2.09 (0.45, 9.81) for severe OSA |

[76] | Meta-analysis |

Note: aRR: Adjusted Relative Risk; aHR: Adjusted Hazard Ratio

Table 9: Strength of Association between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cancer Outcomes.

Overall mortality

Several meta-analyses are unanimous in declaring that OSA is associated with an increased risk (range=19 to 92%) of overall mortality, especially in those with severe disease (Table 10). A meta-analysis on death and disability in sleep apnea syndrome confirmed a significant increase not in only in cardiovascular but also non-cardiovascular deaths in those with sleep apnea [10]. The mechanisms underlying the health consequences of OSA involve the repetitive partial or complete upper airway obstruction causing cyclical airflow limitation associated with oxygen desaturation and reoxygenation, intrathoracic pressure fluctuations resulting in hemodynamic variations, and electroencephalographic arousals associated sympathetic activation. Nocturnal respiratory dysfunction (i.e., hypoxemiareoxygenation and hypercapnia), poor sleep quality (i.e., increased arousals, poor sleep efficiency, decreased Stages N3 and REM), and intrathoracic pressure variations, in addition to shared comorbid risk factors (e.g., BMI, metabolic syndrome, etc.), promote oxidative stress, inflammation, sympathetic activation, endothelial dysfunction, neurohormonal changes, thrombophilia, and hemodynamic changes, which are the known pathophysiologic mechanisms of the adverse systemic outcomes in OSA (Figure 2) [77].

| Survival Outcomes | Strength of Association, Point Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

References (Author, Year of Publication) |

Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death from all causes | HR=1.19 (1.00, 1.41) for moderate OSA HR=1.90 (1.29, 2.81) for severe OSA RR=1.92 (1.38, 2.69) for severe OSA RR=1.66 (1.19, 2.31) OR=1.61 (1.43,1.81) RR=1.59 (1.33, 1.89) for all-cause mortality HR=1.262 (1.093, 1.431) HR=0.945 (0.810, 1.081) for mild OSA HR=1.178 (0.978, 1.378) for moderate OSA HR=1.601 (1.298, 1.902) |

[78] [16] [10] [9] [100] |

Meta-analysis Meta-analysis Meta-analysis Meta-analysis Meta-analysis |

| Cardiovascular death | OR=2.09 (1.20, 3.65) HR=1.40 (0.77, 2.53) for moderate OSA HR=2.65 (1.82, 3.85) for severe OSA OR=2.52 (1.80, 3.52) |

[7] [78] [10] |

Meta-analysis Meta-analysis Meta-analysis |

| CHF mortality | RR=1.09 (0.83, 1.42) | [79] | Meta-analysis |

| Non-cardiovascular death | OR=1.68 (1.08, 2.61) | [10] | Meta-analysis |

| Sudden cardiac death | HR=1.60 (1.14, 2.24) for AHI > 20/hr | [80] | Retrospective cohort |

| COPD mortality | RR=1.79 (1.16, 2.77) | [22] | Prospective cohort |

| Postoperative mortality Orthopedic Abdominal Cardiovascular |

OR=0.65 (0.45,0.95) OR=0.38 (0.22-0.65) OR=0.54 (0.40-0.73) |

[67] | Retrospective cohort analysis of a nationwide inpatient sample |

Note: HR – hazard ratio; RR- relative risk or risk ratio; OR – odds ratio; OSA – obstructive sleep apnea; CHF – congestive heart failure; COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Table 10: Strength of Association between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Survival Outcomes.

Figure 2: Pathophysiology of the Systemic Adverse Health Consequences of Obstructive Sleep Apnea.

Cardiovascular death

Although Wang and colleagues’ meta-analysis did not find a statistically significant increase in incident fatal and nonfatal CHD events [16], 3 other meta-analyses found a statistically significant relationship between OSA and cardiovascular death [7,10,78]. A meta-analysis of studies focusing on CHF mortality corroborated a significantly elevated risk of death, but only in those with central and not obstructive sleep apnea [79]. A retrospective cohort study found an increased risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in patients with OSA [80]. Predictors of SCD included advanced age (>60 years), moderate-to-severe disease severity (AHI>20), nocturnal oxygen desaturation (mean <93% and minimum <78%) [80]. The severity of OSA appears to worsen QT prolongation in patients with congenital long QT syndrome, thereby raising the risk of SCD in this condition [81].

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality

A prospective cohort study of 213 patients with overlap (COPD and OSA) syndrome not treated with CPAP and 210 patients with COPD without OSA revealed a 79% increase in mortality in the overlap syndrome after almost a decade of follow-up [22]. The primary cause of death was COPD exacerbation.

Perioperative mortality

On the other hand, a nationwide cohort study reported a counterintuitive reduction in post-operative mortality in OSA patients who underwent orthopedic, abdominal, or cardiovascular surgery [67]. One proposed mechanism for this post-operative mortality reduction in OSA patients is the obesity paradox [lower mortality observed in overweight or obese patients with CHF [82-84], acute coronary syndrome [85,86], cardiovascular interventions [84,87,88], AF [89], pneumonia [90], lung cancer [91], and DM [92]. Another proposed mechanism is ischemic preconditioning, in which the intermittent hypoxemia due to OSA confers a wide array of protective end-organ effects. An observational cohort study provided some evidence for this concept of ischemic preconditioning based on lower troponin T levels and, as a corollary, less myocardial damage, in OSA patients suffering from acute myocardial infarction [93].

The published literature on the adverse health consequences of OSA presents convincing evidence that OSA virtually affects every organ system, resulting in poor neurocognitive (i.e., hypersomnolence, fatigue, attention/vigilance, delayed longterm visual and verbal memory, visuospatial/constructional abilities, and executive function) and neuropsychological (e.g., depression, somatic syndromes, anxiety, and attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder), cardiovascular (i.e., CHF, systemic hypertension, ischemic heart disease, AF, ventricular arrhythmia, and stroke), respiratory (i.e., asthma and COPD exacerbation, pulmonary embolism, and pulmonary hypertension), endocrine (i.e., DM, metabolic syndrome, and sexual dysfunction), gastrointestinal (i.e., GERD and NAFLD), obstetric (i.e., pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders, gestational diabetes, maternal cardiovascular, pulmonary, and surgical complications), perinatal outcomes (i.e., low birth weight, preterm delivery, NICU admission, hyperbilirubinemia), surgical outcomes (i.e., post-operative ICU transfer, respiratory complications, cardiovascular events, and neurologic complications), accident-related (i.e., motor vehicle crashes and work-related injuries), and survival (i.e., cardiovascular, noncardiovascular, and COPD, and overall mortality) outcomes. The mechanisms underlying the health consequences of OSA involve the repetitive partial or complete upper airway obstruction causing cyclical airflow limitation associated with oxygen desaturation and reoxygenation, intrathoracic pressure fluctuations resulting in hemodynamic variations, and electroencephalographic arousals associated sympathetic activation. The impairments in nocturnal respiratory function and sleep quality, in addition to comorbid conditions, result in oxidative stress, inflammation, sympathetic activation, endothelial dysfunction, neurohormonal changes, thrombophilia, and hemodynamic changes that lead to increased morbidity and mortality in patients with the OSA. On the other hand, perioperative mortality risk appears to be lower with OSA, purportedly due to the obesity paradox and ischemic preconditioning. Further research will help identify yet undiscovered adverse health effects of OSA, elucidate their pathophysiologic mechanisms, and propose preventive and therapeutic approaches to ameliorating these poor outcomes.

Citation: Espiritu JRD (2019) Health Consequences of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J Sleep Disord Ther 8:307

Received: 18-Aug-2019 Accepted: 22-Nov-2019 Published: 29-Nov-2019 , DOI: 10.35248/2167-0277.19.8.307.

Copyright: © 2019 Espiritu JRD. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited