Gynecology & Obstetrics

Open Access

ISSN: 2161-0932

ISSN: 2161-0932

Research Article - (2019)Volume 9, Issue 9

Background: Midwives from the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Unit at University Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona, have developed a device for the application of thermal therapy on lumbar and suprapubical areas when labour pain appears.

Objective: To assess the beneficial effects of heat application on lumbo-suprapubical pain during initial stages of labour.

Study design: Randomized, parallel, open, non-blind clinical trial.

Methods: Participants were pregnant women in the prodromal, early and active labour (up to 4-5 cm of dilation), with lumbo-suprapubic pain. The study was conducted in the delivery ward of Hospital Universitari Germans Trias I Pujol, in Badalona (Catalonia, Spain) during 2017-2018. One hundred and thirty-four childbearing women giving birth between September 2017 and March 2018 participated. The intervention group (n=67) received local heat at a temperature between 38-39°C on the lumbo-suprapubic areas for 30 minutes using an elastic pelvic belt as a pain relief device and was compared to a control group in which no heat was used. Primary outcomes were: pain level perception measured with a Visual Analogic Scale and a satisfaction index regarding the utilization of the belt device in the intervention group by using a specific ad-hoc non-validated questionnaire designed for the study.

Results: Among the 134 participants: 41% (55) were in prodromal labour, 53.7% (72) in early labour and 5.2% (7) in active labour (up to ≤ 4-5 cm); groups were not balanced for the phases of labour. The pre-intervention pain level in the intervention group was 0.71 points higher (6.28 ± 1.59) than in the control group (5.57 ± 1.87) p=0.02. At 30 minutes of heat application, pain level in the study group decreased 0.65 points (5.88 ± 1.82) while it increased in the control group (6.53 ± 1.85) p=0.046. The difference between basal pain level and post-intervention, was 0.39 ± 1.35 in the intervention group while in the control group it was 0.95 ± 1.11 (p=0.000) in the Visual Analogic Scale. The global satisfaction index for the pelvic elastic belt was 15.38 ± 2.15 (range 5-19) which corresponds to 80.94% over 100% of the maximal punctuation.

Conclusion: Heat application on both lumbar and suprapubic areas in case of labour pain is effective in relieving pain. The heat pads subjection device, a new abdominal two-pocket belt, obtained positive feedback from women in the study group who used it and answered the satisfaction questionnaire.

Randomized clinical trial; Thermal pads; Elastic pelvic belt; Labour pain; Non-pharmacological pain relief

The first signs of labour appear during the prodromal labour and the early labour in term pregnancies. Both phases are characterized by having a variable duration and a progressive increase in the frequency and intensity of uterine contractions. From a clinical point of view, it is accepted that active labour is set when there are regular intense contractions, there is cervical effacement and there is progressive cervical dilatation (The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2017, World health Organization (WHO) 2018).

Support for pain in early phases of labour is of utmost importance and it deserves specific attention and continuous support throughout the entire process when labour pain appears, a wide range of options can be offered in order to relieve it. In case a childbearing woman decides to give birth in a hospital these options include both pharmacological techniques, such as epidural anaesthesia (Committee on Practice Bulletins- Obstetrics, 2017); as well as non-pharmacological techniques, such as: hot water immersion sterile water injections, other alternative support materials or intermittent application of heat and cold pads [1-29].

Midwives in our ward, quite frequently offer local heat application as a pain relief method. Blood vessels dilate with heat, thus improving blood circulation and temporarily blocking the transmission of pain signals to the brain. Midwives from the Obstetrics and Gynecology Unit at University Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol (HUGTiP), Barcelona, have developed a device for the application of thermal therapy on the lumbo-suprapubic areas; the device is a pelvic, elastic, two-pocket belt and registered as a business model (ES20170030826U20170711), which allows placing and hold heat and cold pads on lumbar and suprapubical areas when pain appears.

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the application of lumbo-suprapubical heat during the prodromal, early and active (up to 4-5 cm) labour up in comparison to not application of heat. Secondarily, it also aimed to evaluate the comfort perceived by childbearing women who used the thermal belt.

The randomized, parallel, open, non-blind clinical trial was set up. Participants were childbearing women in the prodromal and early labour and the active first stage of labour up to 4-5 cm of dilation, with lumbo-suprapubic pain. The intervention group received lumbo-suprapubic heat with the thermal belt for 30 minutes and was compared to a control in which no heat or other pain reliever were used during the same period of time. The study was conducted in the delivery ward of Hospital Universitari Germans Trias I Pujol, in Badalona (Catalonia, Spain) during 2017-2018.

The thermal belt is an elastic belt, adjustable to the pregnant woman´s pelvic perimeter without a compressive effect which allows applying thermotherapy on the lumbar and the pelvic areas in order to relieve labour pain. To apply the thermotherapy, heat or cold pads are placed inside each pocket. The two-pocket system makes it easier to remove and to change the pads as well as to wash the different parts. The belt covers both lumbar and suprapubic areas, which are the areas that women refer to be as the most painful during labour (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The thermal belt.

Heat pad temperature is set at 38-39°C and women can eventually use it as much as they want throughout labour. The pads contained linen seeds and the outer shell was made of 100% cotton fabric. The pads were heated in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Unit microwave; previously a seed pads heating pilot study was carried out in order to standardize a heating time and power for the ward´s microwave so that the application temperature on maternal skin did not exceed 38-39°C.

Sample

Childbearing women assisted in our ward during 1) prodromal labour: precursor contractions which do not progress toward delivery; 2) early labour: first perceived regular and persistent uterine contractions that lead to cervical change; 3) active labour (up to 4-5 cm): regular intense contractions that lead to cervical effacement and to progressive cervical dilatation.

Written and oral information about the trial was provided to women at their admittance at the ward.

Women were recruited after signing the written consent. Exclusion criteria included: women in the active first stage of labour >4-5 cm cervix dilation as in most childbearing women assisted in our center epidural anaesthesia for pain relief is started at this point; clinical alterations of the CTG or other previously detected fetal abnormalities, maternal altered coagulation profile and a history of maternal thromboembolism episodes.

A participant woman removing the heat pads before the completion of the 30-minute period was included in the withdrawal criteria; reasons for removing heat pads were collected.

We used Granmo software (version 7.12) to calculate a sample size of 126 participants (63 in each study arm) to detect a minimum difference of 1 point in the Visual Analogic Scale (VAS), using the standard deviation=2 from the study.

Accepting an alpha value of 0.05 and a beta value of 0.2 in a bilateral contrast.

We did not consider attrition during our calculations given that participants were included prospectively until reaching the necessary sample size; however extra randomised envelopes had been prepared and when inclusion phase concluded.

We had recruited 141 women and 134 were finally analysed.

We hypothesized that the application of heat pads on lumbar and suprapubic areas for 30 minutes would reduce the pain level by at least 1 point in the VAS compared to controls, and that these differences would be statistically significant.

Rigour

Participant childbearing women were selected through nonprobabilistic accidental sampling. The research nurse from HUGTIP obtained a random number table for two study groups. Allocation to the parallel study arm was determined using sealed, opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes, which contained information indicating group assignment and were prepared by one of the team investigators.

Midwives in charge of the childbearing women offered those who met the inclusion criteria to participate; if they accepted and once the written consent was signed, midwives assigned participant women to the intervention group picking the following envelope which contained the group allocation.

The independent variable was the application of lumbosuprapubical heat seed pads using the thermal belt when pain associated with early stages of labor was detected. We chose a 30 minutes application period based on hot water application and 38-39°C for both mother and fetus was demonstrated to be safe. Also, the following dependent variables were defined:

1) Pain level at baseline (T0) measured with the Visual Analogic Scale (VAS); and pain level 30 minutes after the intervention (T30) in both groups, also measured with the VAS

2) VAS variation (Δpain): defined as the pain level difference between perceived pain at baseline and perceived pain 30 minutes after the intervention

The use of the thermal belt was evaluated in the study group with an ad hoc satisfaction questionnaire. It contains 5 Likert type questions which rate 1 to 4 and form a global satisfaction index; the minimum satisfaction level was 5 and 19 was the maximum. Three open questions were added in order to get a qualitative approach to thermotherapy and belt use.

Other variables were: age, labour stage, TPAL formula (Term, Preterm, Abortion, Living), pregnancy weeks, amniotic membranes integrity, labour augmentation, peridural anaesthesia, type of birth, Apgar test punctuation, and perceived comfort using the thermal belt measured with the satisfaction questionnaire in the intervention group.

Intervention characteristics

Sociodemographic and clinical variables were registered in both groups as well as the first pain level measurement (T0) with the VAS, before any intervention. After that:

• The control group received the usual care provided by midwives during labour but without the application of local heat on the lumbo-suprapubic areas or another pain relief method during the 30 minutes intervention period. After the 30 minutes intervention period women in the control group were offered pain relief methods including heat pads

• The intervention group received the usual care provided by midwives during labour and local heat on the lumbosuprapubic areas using the thermal belt as a pain relief method during the 30 minutes intervention period. After the 30 minutes intervention period women in the study group could eventually keep on using the thermal belt and were offered other pain relief methods if required

• In both groups pain level was reevaluated after 30 minutes. Women in the intervention group could use the thermal belt for as long they wanted but were considered withdrawals if they did not use the heat pads for the first 30 minutes; it happened in four recruited women and when asked, women said they removed the head pads due to not feeling comfortable with heat. The comfort perceived by women in the study group while using the thermal belt with the heat pads, was measured with a specific questionnaire that women filled in for themselves/on their own/without guidance.. So they could freely give their opinion about the heat and the belt and afterward were handed in before leaving to maternity ward after giving birth. In order to ensure safety during the intervention, maternal and fetal vital signs were monitored, including blood pressure, temperature and heartbeat rate for the mother, and CTG registration in labour and Apgar test (1-5-10 minutes after birth) for the fetus

All data analyses were carried out using the SPSS statistical program (v. 24.0 for Windows, Spanish version). Descriptive and inferential analyses were conducted. Quantitative variables are expressed as means and standard deviations, and qualitative variables as percentages. Paired Student’s t-test was used in the hypothesis contrast in case of paired values and analysis of variance (ANOVA) in case of more than two groups. Basal results were adjusted using a general linear model. Categorical variables were analyzed with Pearson’s x2 or Fisher’s test and continuous and ordinal variables with the Mann-Whitney U-test or the Kruskal-Wallis test, as appropriate. All reported p-values are two-tailed. p<0.05 was considered to denote statistical significance. A statistician participated and helped with the linear model.

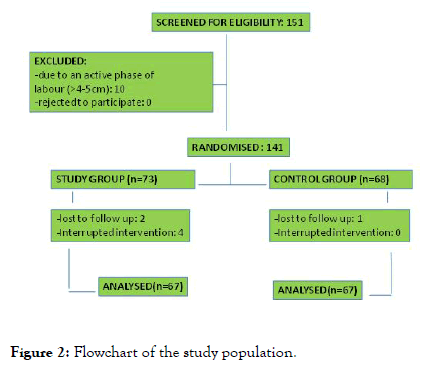

One hundred and forty-one childbearing women were randomized: 3 were lost due to a lack of follow-up: childbearing women in the prodromal labour who finally gave birth in another centre; 4 women in the intervention group removed the heat pads before the minimum treatment time (30 minutes), when asked, women said they removed the head pads due to not feeling comfortable with heat. One hundred and thirty-four women composed the final sample: 67 in each group. A flowchart of the study population is illustrated in (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Flowchart of the study population.

Mean pregnancy weeks were 39.0 ± 1.6; women´s mean age was 30.6 ± 5.9 years; 60.4% (81) were nulliparous, 25.4% (34) were primiparous and 14.1% (19) had two or more previous deliveries.

At the inclusion, 41% (55) of women were in the prodromal labour, 53.7% (72) were in the early labour and 5.2% (7) were in active labour up to 4-5 cm; 59% (79) of women had a full amniotic sac: 70.1% (47) in the intervention group, 48.5% (32) in the control group, this difference was statistically significant; thermotherapy application results will show that pain level at baseline was significantly higher in the intervention group despite a higher percentage of membranes integrity. Oxytocin augmentation occurred in 73.1% (98) of labours and 82.1% (110) of women requested for epidural anaesthesia. Type of birth was as follows: 53.7% (72) eutocic, 19.4% (26) instrumented (obstetric vacuum, forceps), and 26.9% (36) caesarean (Table 1).

| Study group | Control group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | %(n)/X ± DS | %(n)/X ± DS | Statistical sign |

| Age (years) | 30,37 ± 5,43 | 30,96 ± 6,36 | 0,570* |

| Pregnancy weeks | 38,96 ± 2,03 | 39,07 ± 1,18 | 0,704** |

| Parity | |||

| Nulipara-primipara | 86,6% (58) | 82,1% (57) | 0,804*** |

| Multipara | 13,4% (9) | 15% (10) | |

| Stage of Labour | |||

| Prodromal | 43,2% (29) | 38,8% (26) | 0,396*** |

| Early Labour | 49,2% (33) | 58,2% (39) | |

| Active Labour ≤ 4-5 cm | 7,4% (5) | 3% (2) | |

| Membranes integrity at intervention | 70,1% (47) | 48,5% (32) | 0,011*** |

| Oxitocin augmentation in labour | 75,4% (49) | 75,4% (79) | 1*** |

| Peridural analgesia in labour | 81,5% (53) | 87,7% (57) | 0,331*** |

| Type of birth | |||

| Eutocic | 53,73% (36) | 53,73% (36) | 0,199*** |

| Instrumented (vacuum, forceps) | 23,8% (16) | 14,9% (10) | |

| Cesarean delivery | 22,3% (15) | 31,34% (21) | |

| Apgar test punctuation (1 min) | 8,66 ± 1,27 | 8,98 ± 0,48 | >0,05** |

| Apgar test punctuation (5 min) | 9,75 ± 0,79 | 9,98 ± 0,12 | >0,05** |

Table 1: Demographics and baseline characteristics of the study population.

The pre-intervention pain level in the intervention group, measured with the VAS, was 0.71 points higher (6.3 ± 1.6) than in the control group (5.6 ± 1.8) p=0.02 (t-test). After 30 minutes, pain level in the intervention group decreased 0.65 points (5.8 ± 1.8) while it increased significantly in the control group (6.5 ± 1.8) p=0.046 (t-test). Comparing pre and post-intervention pain levels (Δpain), in the intervention group pain decreased 0.4 ± 1.4 and in the control group it increased 0.9 ± 1.1, which represents a significant difference of 1.3 points p=0.0001 (t-test) between groups pain variation. Δpain was adjusted by a linear model; this additional analysis also shows significant difference in the Δpain between groups (Table 2).

| Adjustment | VAS score difference | Stat. Significance | CI (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (independent variables) | (dependent variable) | ||

| Basal data | 1,351 | 0,0001 | 0,927-1,774 |

| VAS 1 | 1,215 | 0,002 | (-)0,311-0,073 |

| Other variables: | |||

| Labour stage and Membranes integrity and Parity | 1,171 | 0,0001 | 0,759-1,583 |

Table 2: VAS difference adjusted by a general linear model.

Women with ruptured membranes are likely to feel increased pain; VAS comparison results showed statistical differences considering membranes integrity: women with a broken amniotic sac scored significantly higher in the VAS compared to women with a full amniotic sac in both groups when measuring pain at baseline and pain after 30 minutes. Women with ruptured membranes felt more pain than women with full membranes in both groups, but the analysis of Δpain showed no statistical differences in the pain level evolution comparing full to ruptured membranes. The analysis of variance of the Δpain considering membranes integrity, labour stage and parity showed statistical difference in the control group labour stage: pain after intervention increased 0.4 ± 0.7 in the prodromal labour, 1.3 ± 1.2 in the early labour, 1.7 ± 0.3 in the active labour (up to 4-5 cm) p=0.02 (ANOVA) (Table 3).

| X ± DS | Sign | X ± DS | Sign | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membranes integrity | |||||

| Yes | 5,96 ± 1,62 | 6,031 ± 1,77 | |||

| No | 7,027 ± 1,27 | 0,012* | 5,10 ± 1,88 | 0,044* | |

| Labour stage | |||||

| Prodromal | 6,19 ± 1,60 | 5,71 ± 1,89 | |||

| Latent | 6,21 ± 1,68 | 5,48 ± 1,92 | |||

| Active | 6,90 ± 0,74 | 0,649** | 5,50 ± 0,71 | 0,895** | |

| Parity | |||||

| Nuliparous | 6,10 ± 1,59 | 5,65 ± 1,96 | |||

| Primiparous | 6,82 ± 1,67 | 5,50 ± 1,94 | |||

| Multiparous | 6,12 ± 1,35 | 0,338** | 5,08 ± 1,35 | 0,774** | |

| *T student; **Anova |

Table 3: Compared pre-intervention VAS ratings between groups.

Thermotherapy application device: Satisfaction questionnaire results

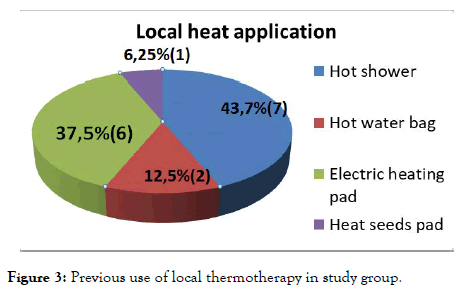

Women in the study group filled in the satisfaction questionnaire regarding the perceived pain relieve effect of the heat pads and the use of the pelvic belt; 34.3% of them (n=23) already knew about the use of heat application to relieve labour pain and from those 23, 16 (76.2%) had previously used heat somehow at their homes, which consisted in hot shower in 43% (n=7); electric heating pad in 37.5% (n=6); hot water bag in 12.5% (n=2) and hot seeds pad 6.25% in one case (Figure 3). The mean satisfaction score was 15.4 ± 2.1 (5-19), which corresponds to 80.9% over 100% (Table 4). Using the thermal belt was felt as comfortable for 95% of the intervention group (n=44), practical for 90.9% (n=30) and pleasant for 97% (n=32).

Figure 3. Previous use of local thermotherapy in study group.

| Satisfaction Questionnaire Results (N=67) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| %(n) | %(n) | |||

| 1- Did you know that heat can be used to mitigate labour pain? | Yes 34,3% (23) | No 65,7% (44) | ||

| 2.1- Have you ever used any method to apply local heat? | Yes 76,2% (16) | No 23,8% (5) | ||

| 2.2- In case you answered yes in the previous question: which one? | Hot shower 43,7% (7) | Hot water bag 12,5% (2) | Electric pad , 37,5% (6) | Seeds pad 6,25% (1) |

| 3- To put the elastic belt around your abdomen was | Difficult 1,5% (1) | Easy 65,7% (44) | Very easy 32,8 (22) | |

| 4- The possibility of putting heat on abdomen and lumbar area at the same time in case of pain is | Very useful 37,3% (25) | Quite useful, 49,3% (33) | Not too useful, 11,9% (8) | Useless 1,5% (1) |

| 5- The elastic belt kept the seed pads on the painful areas | Totally 62,7% (42) | Parcially 34,3% (23) | Did not cover 3% (2) | |

| 6- Using the elastic belt felt | Comfortable 95,7% (44) | Pleasant 97% (32) | Practical 90,9% (30) | |

| 7- Adapting the elastic belt to your abdomen was | Very easy 41,8% (28) | Quite easy 55,2% (37) | Little bit difficult 3% (2) | |

| 8- If you could use the elastic belt with the seed hot pads at home when you felt pain, you would use it | Never 4,5% (3) | Sometimes 32,8% (22) | Frequently 34,3% (23) | Always 28,4% (19) |

Table 4: Satisfaction questionnaire results.

The questionnaire included a section for open comments where 6 women wrote: “while I was using it, I felt that the contraction pain decreased” (1 comment); the hot seeds smelled pleasantly for one woman and unpleasantly for another (2 comments); “a hot-cold contrast could also be useful to mitigate pain I guess, I would have liked to try that” (1 comment) and the belt with the two heat pads in its pockets felt a little bit heavy for two women (2 comments). Authors have literally copied the comments written by participant women. No other comments were written in the questionnaires section for open comments.

Midwives quite frequently offer local heat application as a painrelief method in labour. This clinical trial evaluated the effectiveness of applying heat pads on both lumbo-suprapubic areas with an elastic belt during the onset of labour. Results confirm that local heat application diminishes pain levels in early stages of labour.

In the reviewed literature, applied hot water pads (38-40°C) on abdomen, suprapubic and lumbar areas for 30 minutes followed by the application of cold, using ice bags for 10 minutes during first stage of labour. Shirvani and Ganji used cold on abdomen and lumbar area for 10 minutes every 30 minutes as a pain relief method; Ghani applied hot water pads on both lumbosuprapubic areas for 15 minutes and ice bags on both hands as acupuncture treatment while women were lying on their left side. In all these studies a significant VAS rating decrease in the study group was observed.

Taavoni, applied heat on the sacrum-perineal area obtaining also a significant VAS rating decrease; in a further study they also evaluated the heat application (1st intervention group) and the use of the birth ball (2nd intervention group) compared to a control group (3rd group) and pain diminished significantly in both intervention groups.

In our study, we chose to apply only heat because in our ward cold is not frequently offered as a pain relief method. We used to study standard deviation for the sample size estimation and their 30minutes heat application adapted to seed pads on both lumbo-suprapubic areas. Our results also showed a significant VAS rating decrease in the study group, thus confirming the effectiveness of heat application.

The fastening system used to adjust the thermal pads to the woman´s body is a relevant issue when women use local heat and they move at the same time. Applied the hot and cold pads with towels; Ghani did not mention the fastening system although they describe that women lay on their left side during the intervention. In the present study, women were able to move freely while heat pads were applied to both lumbar and suprapubic areas. One main reason that motivated the development of our thermal belt was to allow normal mobility of pregnant women who would use it. It is known that specific pelvic support devices already exist. Most of them are support belts meant to relief mechanical pregnancy backaches; some of them are abdominal bands adapted to the pregnant woman´s body characteristics; some others are pelvic support belts meant to diminish pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy or postpartum. Nevertheless, none of these devices have been specifically designed to apply thermotherapy on both lumbar and suprapubical areas during pregnancy or labour.

Finding out the women´s satisfaction level after using the thermal belt was one secondary but important issue in this study. Some authors used the VAS scale to measure the satisfaction level. In Taavoni´s study about the application of sacro-perineal heat, significantly higher satisfaction levels were obtained in the experimental group; Abdolahian´s study about movement and lumbo-sacral massage in first stage of labour, also obtained similar satisfaction levels. Both stated that the VAS was a rather rudimentary tool for measuring satisfaction levels. Ghani used the State Anxiety Inventory (SAI) translated and validated to Arabic as a complement to the VAS; their results showed a progressive increase of anxiety levels in both groups although in the study group that increase was significantly lower than in the control group. Ganji used an ad hoc 5-Likert-typeanswer questionnaire in which 43% of women reported high satisfaction levels. In the present study, the analysis of the answers showed that very few women in the study group had previously used local heat as a pain relief method and only one had used hot seed pads before.

In the present study, we chose the VAS to measure pain but created an ad-hoc non-validated questionnaire to find out the women´s satisfaction level after using local heat applied with the belt. Women in the study group answered the questionnaire by themselves/on their own and handed in it before leaving the maternity ward. The satisfaction index ratings support the use of the thermal belt as a specific device for the application of local heat.

Most of the reviewed studies applied local thermotherapy throughout the first stage of labour. They used one specific treatment pattern during first stage of labour and a different one during delivery, also measured pain levels several times along the process. Ghani measured pain levels at 3, 6 and 8 cm of cervical dilatation while women were lying on their left side. Abdolahian measured pain levels every 30 minutes until complete cervical dilatation (10 cm). Taavoni also measured pain levels every 30 minutes until 120 minutes after the intervention; women were lying during intervention in order to diminish bias related to mobility; women in control group did not receive other comfort measures.

In the present study, women could move and change their position freely throughout labour which means they could continue to walk, sit or lay in bed as they chose even during the intervention. No pain evaluations were made at certain dilation centimeters because it is not recommended to do routine vaginal explorations under 4 hours if labour progress is correct (WHO 2018) and we cannot compare this aspect to other studies results. No other pain evaluations for the study were made beyond the start of the active phase of labour due to the great variability of the labour duration and the perceived pain intensity each woman can experience.

This study has limitations. Despite randomization, there is a statistical difference in the pre-intervention pain level between groups. Higher pain levels were found in the study group which decreased significantly after the intervention, while it was the other way round in the control group, lower pain levels were scored before the intervention which increased significantly after the intervention.

In order to find any possible bias, further statistical analyses were carried out: a general linear model was applied in order to adjust the variable “VAS difference”, and an analysis of variance was done with those variables which could influence the pain perception: membranes integrity, labour stage and parity, and these variables did not change our results.

Women with ruptured membranes are likely to feel increased pain; VAS comparison results showed statistical differences considering membranes integrity: women with a broken amniotic sac scored significantly higher in the VAS compared to women with a full amniotic sac in both groups when measuring pain at baseline and pain after 30 minutes, but the pain rating evolution was similar afterward as no differences were found between groups in the Δpain. This variable, showed a significant difference in the control group labour stage: women in the prodromal labour (those who went home because they were not yet in labor) did not almost increase their pain scores after 30 minutes compared to women in the early and active labour who significantly increased their pain ranking in the VAS after 30 minutes.

Pain is a subjective perception and therefore the same process involves different pain levels for different people. It is also known that labour pain increases as dilation progresses. This is the main difficulty in this study and in order to minimize the differences in labour pain level, depending on the labour stage, women in active labour from 4-5 cm were excluded.

We did not count on previous pain level assessments from participant women.

The application of local heat on both lumbo-suprapubic areas during labour is effective and the device developed by professionals from HUGTiP and IGTP from Badalona obtained a positive response amongst pregnant women who used it.

The institutional Ethics Committee for Clinical Research approved the study (PROTERMIC PI-17-092), as did the hospital´s nursing management and the Obstetrics and Gynecology Unit´s management. Written and oral information about the trial was provided to women at their admittance at the ward. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants childbearing women before they were in pain. The ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed, and the study was registered in EUDRA-CT registry as a clinical trial (2018-001465-16).

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

This study was undertaken through internal funding provided by the University Hospital Germans Trias I Pujol (HUGTiP) and the Germans Trias I Pujol Research Institute (IGTP). No other bodies or groups contributed funds towards the evaluation nor played a role in the analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Trial registration: EUDRA-CT 2018-001465-16

LT invented and designed the device (the thermic belt); codesigned the clinical trial, undertook the leadership of data collecting and transferring it to a database, worked in analysis results interpretation, wrote the initial draft and translated it to English.

IP and IN approved of the clinical trial design, cooperated in data collecting leadership and transferring it to a database, assisted with the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

SC and MP assisted with the analysis and worked in the analysis results interpretation, assisted with the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

SA co-designed the clinical trial, provided a safe database, led the analysis and worked in the analysis results interpretation, assisted with the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

We thank Nuria Marti Ras, Maria Ortega, Marc Cusachs for their continued support in the device business model protection; Ana Freire for her help with the thermal belt prototypes; Marina Tarrats for her revision of the manuscript translation; and all delivery ward midwives at HUGTiP for so willingly collaborating and being diligent and careful in recruitment and data collection.

Citation: Tarrats L, Paez I, Navarri I, Cabrera S, Puig M, Alonso S, et al. (2019). Heat Application on Lumbar and Suprapubic Pain During the Onset of Labour Using a New Abdominal Two-Pocket Belt: A Randomized and Controlled Trial Gynecol Obstet (Sunnyvale) 9: 511. doi: 10.35248/2161-10932.19.9.511

Received: 17-Sep-2019 Accepted: 02-Oct-2019 Published: 09-Oct-2019

Copyright: © 2019, Tarrats L, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited