Journal of Clinical Toxicology

Open Access

ISSN: 2161-0495

ISSN: 2161-0495

Case Report - (2024)Volume 14, Issue 5

Introduction: Acanthaster planci (crown-of-thorns starfish) is a known coral reef predator found in tropical waters. Despite increasing human encounters, there is limited documentation on the hepatotoxic effects of Acanthaster planci (A. planci) envenomation. We present a rare case of hepatotoxicity following envenomation, contributing to the scarce literature.

Case summary: A 70-year-old male presented with immediate sharp pain after brushing against the crown of an A. planci during a scuba diving trip in Moorea Island, French Polynesia. Initial evaluation in a local Emergency Department (ED) revealed febrile convulsive episodes, and the patient was subsequently discharged. He was readmitted with elevated liver enzymes Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) 650 U/L, Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) 550 U/L), and was treated with antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis. On returning to the USA, further labs showed persistent hepatotoxicity (ALT 607 U/L, AST 310 U/L) and retained spines in his left leg. The patient was managed with N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) and antibiotics (doxycycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole), with improvement in liver function, but Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) remained elevated. Surgical debridement was deferred. The patient is under outpatient follow-up with no residual symptoms.

Discussion: The venom of A. planci contains asterosaponins, toxins with known hepatotoxic effects in animal models. While only two human cases have been reported, this case further highlights the potential for hepatotoxicity and the challenges in managing retained spines and systemic effects. Surgical debridement may not always be required if significant clinical improvement is seen.

Conclusion: A. planci envenomation can lead to significant hepatotoxicity. Proper wound care, antibiotic coverage, and monitoring of liver function are essential. Further studies are needed to determine the role of NAC, surgical intervention, and long-term follow-up in these patients.

Acanthaster planci; Thorns starfish; Hepatotoxic effects; Venom

Acanthaster planci, also known as the crown-of-thorns starfish, is a natural enemy of coral reefs and is ubiquitously found on coral reefs in the tropical waters of the Red Sea, Indian and Pacific Oceans, and the Gulf of California. Due to global warming and environmental destruction of the sea impacting predator-prey dynamics, A. planci has been implicated in abnormal outbreaks in Australia, and the Ryukyu Islands in Japan among other areas6. There have been at least 91 documented cases of injuries by contact with the spines of A. planci according to the documentation by Okinawa Prefectural Institute of Health and Environment between 1998 and 2011 in Okinawa Prefecture. A. planci is the only member of the starfish group to have the toxin complex of asterosaponins in its numerous spines. Asterosaponins have been studied since 1978 with scarce data available of their impact in animals without any formal studies in humans. Effects of envenomation were not documented in humans until the first published case report of A. planci envenomation in 2008 and another case report of anaphylactic shock and liver injury in 2014 [1,2]. To our knowledge, this is the third such case documenting crown-of-thorns (A. planci) envenomation and its impact on humans leading to hospitalization.

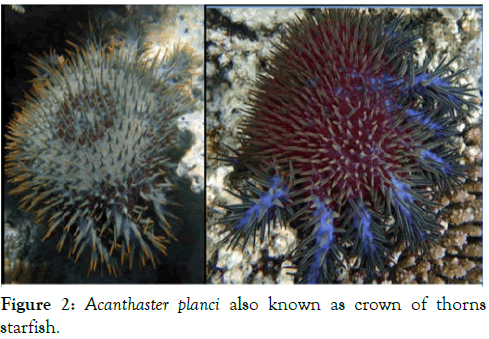

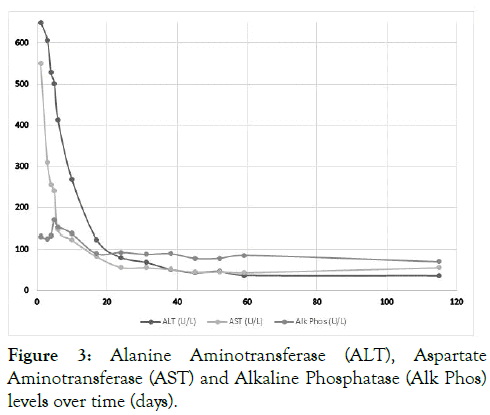

A 70-year-old vacationing male scuba diving off the coast of Moorea, French Polynesia brushed against the crown of an A. planci (Figure 1), with immediate sharp stabbing pain despite the removal of spikes. The patient was taken to a local ED where he was given a tetanus injection, the wound was cleaned and some of the spines were removed. The patient was febrile with a witnessed convulsive and syncopal episode and readmitted after short discharge with vitals at that time notable for Blood Pressure (BP) 190/85, Heart Rate (HR) 274, temperature 103°F, ALT 650 U/L, and AST 550 U/L. The patient was given morphine and started on oral amoxicillin/clavulanate. On day 3, the patient flew back to the USA and was admitted to our facility with a temperature of 100°F. The physical exam was notable for multiple retained thin spikes to the left anterior leg. Labs were notable for both Complete Blood Count (CBC) and Basic Metabolic Panel (BMP) unremarkable but found to have ALT 607 U/L, AST 310 U/L, ALP 125 U/L, T. Bili 0.5 mg/dl. Computed Tomography (CT) of the leg showed multiple retained spines in the leg which were further localized as 6 hyperechoic foci. Toxicology and hepatology were consulted who felt the removal of thorns was paramount to stopping further liver injury based on previous case reports while the patient was started on NAC 140 mg/kg followed by 70 mg/kg, doxycycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Orthopedic surgery was also consulted but ultimately in shared decision-making with the patient surgical intervention was not pursued. Patient coagulation parameters remained normal and liver function tests gradually downtrend to AST 146 U/L, and ALT 413 U/L, but ALP remained elevated at 153 U/L. The patient continues to recover in an outpatient setting with monthly follow-up and no loss of limb function or remaining symptoms (Figure 2 and 3).

Figure 1: Acanthaster planci envenomation progression.

Figure 2: Acanthaster planci also known as crown of thorns starfish.

Figure 3:Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT), AspartateA. planci Aminotransferase (AST) and Alkaline Phosphatase (Alk Phos)A. planci levels over time (days).

The dorsal surface of A. planci is covered with thorn-like spins filled with steroidal oligo-glycoside toxins called asterosaponins that were first isolated from A. planci in 1978 by Kitagawa et al. [3]. New asterosaponin molecules from A. planci are isolated as recently as 2019 but their role for their hemolytic, antineoplastic, cytotoxic, antitumor, antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory properties since 1980 [4]. The primary function of these asterosaponins is for defense and opening up shellfish constrictor muscles via paralysis [5]. In 1990, an autopsy of mice injected with these toxins showed a change in the color of liver, swelling of the gallbladder, and jaundice with elevation in Glutamic Oxaloacetic Transaminase (GOT), Glutamic Pyruvic Transaminase (GPT), Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH), Acid Phosphatase (ACP) and ALP implicating its role as a potent hepatotoxin. Interestingly, hepatic ALP also increased markedly but hepatic GOT, GPT and ACP, LDH showed a tendency to decrease first [6].

To the best of our knowledge to date, there are only two known published case reports in humans documenting clinical course and lab work with one patient suffering anaphylactic response (patient A) and the other (patient B) with a similar course with hepatoxicity as seen in our patient [1,6]. Patient A was found to have diffuse hepatocellular necrosis throughout the parenchyma and lobuli, sinusoidal dilatation caused by congestion, bile plugs in the canaliculi, and eosinophilic cytoplasm with pyknotic nuclei. No necrosis was observed in any other internal organs. The patient’s lab work was notable for transaminitis and severe hemolysis. Beyond the hepatotoxicity, the patient’s anaphylactic response was attributed to a previous sting 3 months prior as authors argued that a typical A. planci could not produce enough toxin to cause death based on Lethal Dose (LD50) data extrapolated from mice studies.

Patient B had a very similar course to our patient with a subsequent visit to a nearby ED for cleaning of the wound, a single, brief syncopal episode, and subsequent beta-lactam antibiotics. Similarly, tetanus diphtheria toxoid was administered followed by an attempt to remove the spines via surgical debridement. Patient B’s liver function tests took at least 25 days after her initial presentation and 16 days after the surgical debridement to normalize.

From the scarce animal data, only two well-documented cases in humans in current literature, and similarities with our patient few conclusions can be drawn. The number of encounters with A. planci is increasing. More documentation and studies are needed to better elucidate A. planci’s toxin impact on humans. However, Asterosaponins tend to cause severe hepatoxicity. There may also be an impact on blood pressure with a mechanism in animals elucidated by histamine release, elevated levels of histamine in patient A, and 2/3 patients experience syncopal events with a third suffering from anaphylaxis.

Further, scanning electron microscopic examination of the spines reveals that the tips of the spines from the crown-ofthorns starfish have fragile lattice-like structures which make surgical debridement difficult while potentially still leaving behind foreign bodies [7,8]. Although we recommend surgical debridement and removal of spine fragments, however, the role of ongoing systemic toxicity from venom/spine presence remains unclear considering significant symptomatic and lab improvement in our patient without surgical debridement. We recommend treating with broad-spectrum antibiotics covering skin flora among other abscess-forming polymicrobial.

In conclusion, little is known about the clinical significance of the potential for toxicity from crown-of-thorns starfish in humans. It is prudent to avoid contact with the crown-of-thorns starfish and attempt to remove spines with adequate wound cleaning, antibiotics covering for polymicrobial infections, and trending liver enzymes. Currently, there is an unclear role of using NAC, surgical debridement to remove all spines, steroids for superficial wounds to prevent contact dermatitis and the duration of follow-up to trend labs.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Arif MZ, Afzal D, Hernandez S, Holmes JF, Albertson TE (2024). Hepatotoxic Effects of Acanthaster planci Envenomation: A Rare Case with Review of Literature on Crown-of-Thorns Starfish Sting. J Clin Toxicol. 14:575.

Received: 30-Aug-2024, Manuscript No. JCT-24-34417; Editor assigned: 02-Sep-2024, Pre QC No. JCT-24-34417 (PQ); Reviewed: 16-Sep-2024, QC No. JCT-24-34417; Revised: 23-Sep-2024, Manuscript No. JCT-24-34417; Published: 30-Sep-2024 , DOI: 10.35248/2161-0495.24.14.575

Copyright: © 2024 Arif MZ, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.