Journal of Antivirals & Antiretrovirals

Open Access

ISSN: 1948-5964

ISSN: 1948-5964

Research Article - (2019)Volume 11, Issue 1

In France, the care pathway for PWID is not straightforward, even among prevention and treatment addiction centres. The aim of this study was to describe and compare the HCV cascade of care in PWID patients followed up in such centres from 2012 to 2017, namely before the 2014 era of interferon-based treatment until the 2014 advent of DAA therapy onwards. The study included an educational component, along with the setting up of a care pathway with an integrated and multidisciplinary approach. 1054 PWID were evaluated, 242 from the interferon-based treatment period and 812 from DAA. Poly-addiction was common, mainly including tobacco (88%) and alcohol consumption (54%). Among the PWID, 77% were screened for anti-HCV, with 34% of them being positive. Besides, 75% of PWID positive for anti-HCV were tested for RNA-PCR, with 68% of them being positive. Among the 140 PWID with HCV infection, 73% were treated with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin or DAA, with 90% of them considered as cured. The proportion of treated PWID cases significantly increased with the advent of DAA drugs: 85% vs 32% with interferon (p=0.027), as did the proportion of cured PWID (95% vs 55%, p<0.001). Conversely the detection rate of anti-HCV and RNA-PCR levels did not differ between both periods, neither did the positivity of anti- HCV, nor that of RNA-PCR. The integrated and multidisciplinary approach and the incorporation of the cure of hepatitis C into the risk and harm reduction strategy proved to be paramount.

Hepatitis C; PWID; DAA; Cascade of care

CSAPA: Centres de Soins, d'Accompagnement et de Prévention en Addictologie; DAA: Direct-Acting Antivirals; HCV: Hepatitis C Virus; PWID: People Who Inject Drugs; RHR: Risk and Harm Reduction; SVR: Substained Virologic Response

The fight against hepatitis C proves to be a major challenge in the French National Health Strategy for the forthcoming years 2018-2022, harboring the goal of completely eliminating hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) until the year 2025 [1]. The main HCV reservoir is to be found among people who inject drugs (PWID). In 2018, 115,000 patients await treatment with direct-acting antivirals (DAA), 50% of whom are PWID [2-5]. In France, the care pathway for PWID is not straightforward, even among prevention and treatment addiction centers. These centers, named CSAPA (Centres de Soins, d'Accompagnement et de Prévention en Addictologie), were created in 2008, based on the merger of specialized drug addiction clinics and alcohol abuse outpatient centers [6].

The first cascades of care, described for HIV infection [7-9], have proven to be effective tools for improving the health of people living with HIV, attaining the designed public health benefits of antiretroviral therapy [10]. The cascades of care comprise successive steps from screening to diagnostic assessment, eventually resulting in treatment and healing. Most data evaluating the HCV cascade of care were reported prior to the time when DAA were first considered as the standard of care. One of the most frequently-cited publication reported that as of July 2013, among the 3.5 million people estimated to suffer from chronic HCV in the United States, 16% were prescribed treatment, with only 9% achieving sustained virologic response (SVR) [11]. Progression through the cascade of care was demonstrated to vary wildly, whilst often limited by multiple barriers. In specific populations like PWID, these barriers were linked to human factors, such as lack of information, ignorance of illness and treatment, absence of insurance coverage, in addition to structural factors like the lack of means and of coordination, along with geographical isolation [12,13]. With the advent of DAA, the HCV cascade of care could be markedly transformed, whereas several barriers should likely remain [14].

This study aimed to describe and compare the HCV cascade of care in PWID patients followed up in the Alsatian territory CSAPA from 2012 to 2017, namely before the 2014 era of interferon-based treatment until the 2014 advent of DAA therapy onwards.

Patients

PWID patients were included from December 2012 to September 2017 and followed-up in eight different CSAPA, among which five hospital-based and three city-centers. Medical doctors, either general practitioners or addiction specialists, proposed study participation to all PWID presenting at CSAPA provided the mobile FibroScan was available, namely over 1 month every 3 months for each centre. The physicians provided a study information sheet to all PWID upon program entry. Once fully informed about the study, the candidates were free to decide whether or not they were willing to participate. The subjects who accepted to enter the study completed and signed a written informed consent form. For each PWID, the socioeconomic and clinical parameters collected were as follows: age, gender, nature of injected drugs, opioid substitution treatment with either methadone or buprenorphine, associated addictive behaviours like alcohol, tobacco, or cannabis consumption, psychiatric comorbidity, precarious situation based on universal health coverage availability, and HCV genotype. PWID with co-infection by HIV or HBV were excluded from participation.

Methods

This observational study was initiated and coordinated by the Strasbourg University Hospital's specialty care centre for the fight against viral hepatitis in Alsace territory (SELHVA or Service Expert de Lutte contre les Hépatites Virales d'Alsace). The program included an educational component, along with the setting up of a care pathway.

The educational program was carried out with the aid of the Alsace region’s main hepatitis patients' association, namely SOS Hépatites Alsace-Lorraine, and designed to raise awareness among PWID. The communication tools comprised associated posters, stickers, forums, as well as individual interviews on risk reduction. A common training course was proposed to both healthcare professionals consisting of medical doctors and nurses, and social or educational professionals consisting of social workers, etc. This training, carried out in each center, comprised workshops on evolving HCV understanding, and practical exercises aimed at measuring hepatic fibrosis using transient elastography with mobile FibroScan (ECHOSENS, Paris, France). Of note is that the FibroScan is a non-invasive means to evaluate chronic liver disease severity by accurately detecting the fibrosis stage on a scale ranging from 0 to 75KPa corresponding to a fibrosis stage from F0 to F4 according to the METAVIR classification (15). The fibrosis was considered severe for Stages F3 and F4 (over 9.5 KPa), with Stage F4 corresponding to cirrhosis. The FibroScan was made available to each center after an e-learning education session using the ECHOSENS platform following a SELHVA-established schedule. The produced elasticity values were interpreted by the same hepatology expert based on classical quality criteria [15].

For all PWID, the setting up of a care pathway including an integrated care was proposed to all centers as follows:

• screening for hepatitis C promoted by the FibroScan use. Classic immunoenzymatic assays were applied to a venous or capillary blood sample. For hospital-based CSAPA, the samples were taken at the center, whereas for CSAPA city centers, the samples were taken at the closest medical analysis laboratory.

• diagnostic assessment involved: i) advanced hepatology consultation after assessing HCV RNA viral load using PCR and genotyping, along with FibroScan and liver ultrasound, yet the latter for severe fibrosis cases only; ii) advanced psychiatric consultation aimed to evaluate or reevaluate addictions and psychiatric co-morbidity.

• indication for anti-viral therapy after changes in guidelines and treatments had been implemented from 2014 onwards [16,17]: pegylated interferon therapy plus ribavirin prior to February 2014 and DAA thereafter.

• post-treatment healing to obtain a SVR defined by undetectable HCV RNA at 3 or 6 months post-treatment.

All the data pertaining to collection and analysis were anonymized and entered into a protected and anonymous electronic record (declaration at the National Commission for Computing and Liberties named CNIL, Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés, number of declaration:1773340v0). The between-group results were compared using standard position and dispersion statistical analyses. For comparison of between-group quantitative variables, such as screened 0/1, analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wallis test were applied, as necessary. All analyses were performed using software R Version 3.1.

In total, 1080 PWID patients were recruited, among whom 14 were excluded from analysis due to lack of study adherence in three cases and FibroScan failure in 11. For 12 other PWID cases, the FibroScan results proved un-interpretable, because of obesity issues. Therefore, 1054 PWID were evaluated, 242 from the interferon-based treatment period and 812 from DAA (Table 1). Most PWID patients were male (80%), with a mean age of 38 years, and heroin as injection drug for the majority of cases, with more than of half of them being on substitution treatment with methadone for two-thirds and buprenorphine for the other third. Poly-addiction was common, mainly including tobacco and alcohol consumption. A psychiatric comorbidity was observed in 20% of PWID patients, and in half of the population, severe fibrosis consisting of F3-F4 Stages was found for 16% of PWID cases. Genotype 1 was observed in 42% of the 140 PWID suffering from HCV infection. Between the interferontreatment and DAA-treatment groups, no statistically significant difference was revealed for any of the parameters tested (Table 1).

| Parameters | Total n=1054 | IFN n=242 | DAA n=812 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) average ± SD | 38 ± 11,7 | 37 ± 13,1 | 39 ± 12,3 | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Proportion of men | 843 | 80 | 194 | 80 | 649 | 80 |

| Injected drugs heroïn cocaïne |

790 495 |

75 47 |

189 109 |

78 45 |

601 386 |

74 48 |

| Opioïd Substitution Treatment | 611 | 58 | 138 | 57 | 473 | 58 |

| Associated addictive behaviors: alcohol tobacco cannabis |

569 927 506 |

54 88 48 |

133 211 116 |

55 87 48 |

436 716 390 |

54 88 48 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | 211 | 20 | 48 | 20 | 163 | 20 |

| Precarious situation | 548 | 52 | 123 | 51 | 425 | 52 |

| Severe fibrosis (F3-F4) |

169 | 16 | 31 | 13 | 138 | 17 |

| Génotype 1 | 59/140 | 42 | 14/34 | 40 | 45/106 | 43 |

Table 1: Socioeconomic and clinical parameters in PWID (IFN= interferon-based treatment, DAA=direct-acting antivirals). No significant statistical difference between the two groups for all parameters

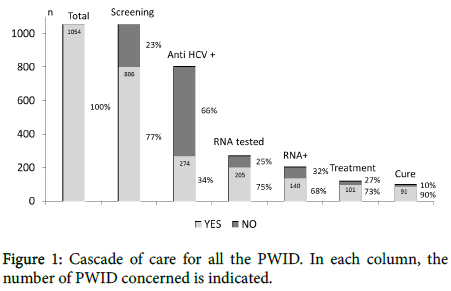

The cascade of care for all PWID cases has been illustrated in Figure 1. Among the patients, 77% were screened for anti-HCV, with 34% of them being positive. Besides, 75% of PWID positive for anti-HCV were tested for RNA-PCR, with 68% of them being positive. Among the 140 PWID with HCV infection, 73% were treated with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin or DAA, with 90% of them considered as cured. The treatment was complete for all PWID cases, excepting two treated with interferon and three with DAA.

Figure 1: Cascade of care for all the PWID. In each column, the number of PWID concerned is indicated.

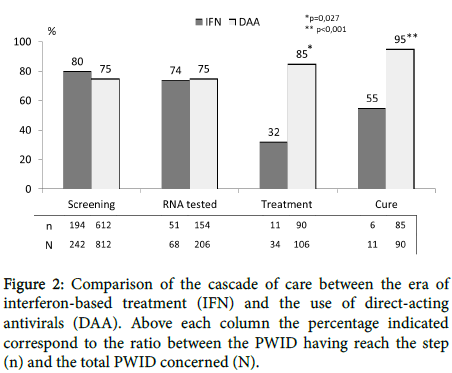

Data comparison between interferon-based and DAA-based treatment groups has been illustrated in Figure 2. The proportion of treated PWID cases significantly increased with the advent of DAA drugs (90/106 [85%] vs 11/34 [32%] with interferon, P=0.027), as did the proportion of cured PWID (85/90 [95%] vs 6/11 [55%], p<0.001) cases. Conversely, the detection rate of anti-HCV and RNA-PCR levels did not differ between both periods, neither did the positivity of anti- HCV (68/194 [35%] vs 206/612 [34%]) nor that of RNA-PCR (34/51 [67%] vs 106/154 [69%], respectively).

Figure 2: Comparison of the cascade of care between the era of interferon-based treatment (IFN) and the use of direct-acting antivirals (DAA). Above each column the percentage indicated correspond to the ratio between the PWID having reach the step (n) and the total PWID concerned (N).

This observational study involving PWID patients followed-up within CSAPA has clearly demonstrated an improvement in the HCV cascade of care following the advent of DAA drugs as compared to interferon-based treatment. It must yet be emphasized that this improvement concerns only the cascade’s last steps, involving increased proportions of treated and cured PWID patients. In our study, the population was well-defined and concerned PWID patients followedup in specialized centers within the same territory, without any hepatitis B or HIV co-infection. The co-infected PWID population does exhibit a different pathway of care in France. In France, the CSAPA are outpatient care services that admit about one-third of PWID patients [3]. As a social healthcare institution, the CSAPA centers display the advantage of being well-placed within communities, offering multidisciplinary care, thereby ensuring long-term treatment and follow-up. The risk and harm reduction (RHR) strategy applied at CSAPA encompasses all those measures aimed at reducing hepatotropic virus contaminations and alcohol consumption (6). In our study, the CSAPA history explains the high frequency of polyaddiction encountered, particularly the co-addiction with alcohol. Otherwise, our cascade of care was completed by means of an integrated care practice, thereby encompassing the successive steps of screening, diagnostic assessment, treatment, and healing. In other studies, however, the cascade of care proved to be rarely complete, which was likewise the case upon interferon-based treatment [18-22] as following DAA [14,23-24] advent. In Wade et al. study [25], the cascade of care concerned all treatment types. Inversely, in our study, the data were separately analyzed between the available treatments. Moreover, the PWID demographic, social, and clinical characteristics did not differ between both treatment periods, which significantly strengthen our study’s impact.

The first step of the hepatitis C cascade of care is screening. To date, numerous PWID patients in France have not yet been screened including recent injectors, PWID from vulnerable groups, occasional users, or ex-users who are often socialized, and thus not yet or no longer in touch with a CSAPA or other addiction center. For this patient population, general practitioners eventually end up being the main link to care [4]. In the CSAPA, the screening proposition proves to be quite variable from one region to another, although screening is clearly recommended by the national health authority [6]. In our study, the screening rate did not differ between the different centers, particularly between hospital-based and city-center associations. In other countries, the screening rate proved to be around 80-90% [18-19,21,24]. In our experience, the detection rate of anti-HCV levels did not progress following the DAA advent, despite the educational program and training course for designed both healthcare professionals and social or educational professionals and conducted in each center. However, standard immunoenzymatic assays applied to venous or capillary blood samples were employed instead of rapid HCV testing [19]. The FibroScan could promote further screening, as this non-invasive technique proves to be well-accepted, with immediate results allowing for awareness of hepatic disease to be provided [26]. In our study, however, this examination was not systematically proposed to all the PWID cases, but only when the mobile equipment was available in each center. The HCV seroprevalence proved to be low in our study (34%), likely translating the early RHR implementation in France [4], particularly in the Alsatian territory CSAPA with generalized syringe distribution in pharmacies and education about safer injection, while providing injection, inhalation, and snorting equipment. In other countries, the seroprevalence rate was demonstrated to be superior, approximating 50% [18-19,21]. In the study of Simmons [27], nevertheless, the seroprevalence proved to be particularly low in drug services, approximating 20%. These disparities are accounted for, at least to some extent, by the seniority of the studies insofar as in more recent studies, seroprevalence was even lower, reflecting the effects of RHR generalization. As demonstrated in the Amsterdam study [28], combining opiate substitution treatment with integrated harm reduction interventions like needle and syringe exchange programs, thereby enabling safer injection practices, likely exerts beneficial effects on reducing HCV transmission.

Concerning the second step of the cascade of care, namely diagnostic assessment, HCV-RNA testing proves to be essential in confirming hepatitis C infection diagnosis. In our study, either general practitioners or addiction specialists proposed testing to three-quarters of PWID, without any difference noted between interferon-based and post-advent DAA treatments. This percentage was in line with that of other studies [21-22,27], excepting the Iversen et al. study [18]. HCV RNA testing was positive in 67% and 69% of our PWID cases, respectively. These percentages were close to those reported by Simmons et al. in drug services from England [27]. The new molecular testing kits that provide a reading of HCV load based on a blood drop taken from the finger prove very promising and should further optimize diagnostic management [28-29]. Other complementary examinations, such as liver enzyme testing and liver biopsy, were not taken into account in our study. Indeed, increased serum transaminase levels were found inconstant, without any liver biopsy made. HCV genotyping was systematically associated by medical laboratory results when HCV RNA was shown positive. Liver ultrasound was only performed for hepatocellular carcinoma screening in PWID cases with severe fibrosis (any case in our study). Next, an advanced hepatology and psychiatric consultation was put on within each CSAPA by means of an integrated and multidisciplinary approach, especially in case of psychiatric comorbidities, alcohol addiction, or precarious situation, which prove quite common based on our experience. Psychological and psychosocial opinions and supports were essential for the therapeutic pre-evaluation in order to provide the most comprehensive care [30,31].

The third step of the cascade of care consists of initiating treatment. Among the cascades of care reported in PWID treated with interferon, <12% underwent treatment in most studies [18-22]. In the Mohamed et al. study conducted in Tanzania, all PWID were not treated for economic reasons [32]. Furthermore, among the cascades of care reported among the general population, 12-20% of patients were treated with interferon, irrespective of the country [11,33-35]. In all these studies, the main barrier to treatment was the fear of interferon side effects [20]. With DAA drugs, the treatment rates were higher in PWID, ranging from 33% [24] to 60% [14], with treatment regimens being completed in most cases, as in our study (87/90, 97%). A higher treatment rate was observed in our study, both in the interferon and DAA treatment groups. Of note is, however, that the number of treatments was limited to 11 with interferon. The SELHVA involvement was probably determinant for achieving these data, with an advanced hepatology consultation to be conducted after HCV RNA viral load had been determined. The integrated and multidisciplinary approach proved, therefore, crucial.

The last step of the cascade is the hepatitis C cure defined by SVR. Among the cascades of care reported in PWID treated by interferon, the RVS rate proved to be very weak, ranging from 3% [18] to 10% [20]. With the DAA advent, the RVS rate increased, attaining between 89% [23] and 97% [14]. Based on experience, while the cure rate associated with interferon proved to be high (55%), this concerned only six PWID patients. Following the advent of DAA drugs, the cure rate was very high, close to that reported by Zuckerman et al. [14]. The integrated and multidisciplinary approach proved to be, once more, paramount, involving permanent psychological and psychosocial support. Moreover, the cure of hepatitis C was totally incorporated into the RHR procedure, strengthening the team memberships within CSAPA.

In conclusion, further efforts must still be made in order to improve HCV screening within CSAPA. More information and further training appear paramount. It must, however, be noted that the results obtained using DAA drugs prove very encouraging in PWID patients followedup in prevention and treatment addiction centers, even for those with poly-addiction, especially alcohol, and with psychiatric comorbidities.

Our thanks go to all the staff of eight CSAPA centers involved in this study and participating to the FibroScan Program (Ithaque, ALT, Colmar House Addictions, Strasbourg, Sélestat, Saverne, Wissembourg, and Haguenau Hospitals), to the SOS Hepatites Alsace Lorraine team and to Dr Gabrielle Cremer for writing assistance.

All authors disclose any potential sources of conflict of interest.

Citation: Michel D, Fiorant DN, Frédéric C, Anais L, Laurence L (2019) Impact of Direct-acting Antivirals on Hepatitis C Cascade of Care amongPeople who Inject Drugs. J Antivir Antiretrovir. 11:179. doi: 10.4172/1948-5964.1000179

Received: 17-Jan-2019 Accepted: 22-Jan-2019 Published: 29-Jan-2019

Copyright: © 2019 Michel D, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Sources of funding : GB´s PhD-project on ethical challenges and decision-making in nursing homes has been financially supported by the Norwegian Extra Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation through EXTRA funds (grant no. 2008/2/0208).