Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-9600

ISSN: 2155-9600

Research Article - (2021)Volume 11, Issue 2

Amaranth grains were used in the present investigation. Amaranth grains were washed grains were spread over filter paper sheet and dried completely. After drying, the grains were ground in an electric grinder to fine powder and supplemented at 20, 40, percent and 60 per cent level in the preparation of chapatti. The chapatti prepared by using wheat flour served as control. The organoleptic evaluations showed that all chapatti prepared incorporating amaranth flour were acceptable. The nutritional analysis revealed that the protein content of control chapatti was 12.42 per cent which increased significantly up to 18.23 per cent with incorporation of amaranth grain flour. The crude fibre and ash content in chapatti incorporated with amaranth flour had increased significantly as compared to control chapatti. Total dietary fibre content ranged from 11.13 to 22.06 per cent in supplemented chapatti whereas control chapatti contained 4.80 per cent total dietary fibre. The results of the study indicated that calcium content ranged from 112.44 to 222.70 mg/100 g in supplemented chapatti, whereas control chapatti had 55.59 mg/100 g calcium. The addition of the amaranth flour to chapatti improved iron, zinc and potassium content significantly.

Amaranth grains; Organoleptic; Chapatti; Protein; Dietary fibre; Mineral content

As previous studies have indicated, under-nutrition in India is not entirely due to an absolute lack of food but implicates a limited diversity in the household diet. Consequently, availability of diverse and more nutrient-rich food crops in the country, education and support in product formulation and recipe development offer viable opportunities for communities to improve their nutrition through dietary diversification and modification. The recent introduction of Grain Amaranth among resource-poor and marginalized communities in some parts of the country is an anticipated opportunity. Grain amaranth is a relatively new plant source of food in Uganda; both the leaves and grains can be consumed. The plant possesses unique nutritional and agronomic attributes, making it a valuable food crop especially among resource-poor and marginalized communities; with potential to contribute to improve nutrition and food security possibly also the alleviation of under-nutrition.

Amaranth grain has high levels of quality protein, whose amino acid composition compares favorably with the protein standard for good health and better than most of the grains and root crops commonly consumed in the country. Grain amaranth is particularly rich in lysine, the most critical essential amino acids that must be present in the diet for good health. It is also rich in fiber and other valuable nutrients including calcium with, twice the amount available in milk. Others include iron that is five times the level available in wheat and higher amounts of potassium, phosphorous, vitamins, A, E and folic acid than available in most cereal grains [1]. The grain is known to contain 6-10% oil, consisting predominantly of unsaturated fatty acids, especially the essential linoleic acid. In addition to the nutritional quality, the crop has a host of beneficial agronomic features including shorter maturity periods, high yields in marginal soils, resistance to stresses such as low moisture and soil fertility.

Grain amaranth production has been promoted in different parts of India before however, the actual contribution of the crop to food and nutrition security state of the communities among which it has been promoted is yet to be determined. Thus, this study sought to assess the potential of grain amaranth to enhance food and nutrition security through addition of amaranth grain for development of value added chapatti.

Procurement and processing of raw material

Amaranth grains were procured in a single lot from the Medicinal Aromatic and Underutilized Plants Section, Department of Genetics and Plant Breeding, College of Agriculture, Chaudhary Charan Singh Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar. Amaranth grains were cleaned and washed under tap water to remove dirt, dust and foreign materials. The washed grains were spread over filter paper sheet and dried completely. For the preparation of chapatti Amaranth grains were cleaned and ground in an electric grinder and flours thus obtained were sieved through a 60 mesh sieve and packed in airtight plastic containers and wheat flour were procured from local market for chapatti development.

Development and organoleptic characteristics of value added Chapatti

Three types of chapattis were prepared by using amaranth flour i.e. Type-I chapatti prepared by using 20% amaranth flour, Type- II by 40% amaranth flour and Type-III by using 60% amaranth flour. Wheat flour chapatti served as control. The preparation method of value added Chapatti is presented in Table 1. All chapatties were organoleptically evaluated by a panel of ten judges for sensory parameters like colour, appearance, flavour, texture, taste and overall acceptability using 9 point hedonic scale (1=dislike extremely, 5=neither like nor dislike, 9 to like extremely). Between tasting different samples, participants rinsed their mouth with warm water.

| S. No. | Ingredients | Control | Type-I | Type-II | Type-III |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wheat flour (g) | 100 | 80 | 60 | 40 |

| 2 | Amaranth flour (g) | 0 | 20 | 40 | 60 |

| 3 | Water (ml) | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| 4 | Salt (g) | 1/2 tsp | 1/2 tsp | 1/2 tsp | 1/2 tsp |

Table 1: Proportion of ingredients used for preparation of chapatti.

Method for preparation of chapatti:

• Wheat flour and amaranth flour were mixed together.

• Salt was added to mixture of flours. Soft dough was made by using water.

• Dough was divided into equal portions; small balls were made and rolled out with the help of rolling pin.

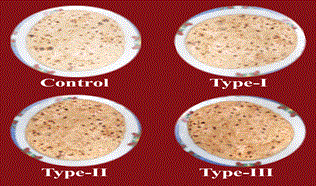

• Chapatis were roasted on a hot griddle from both the sides until brown shown in plate 1.

Plate 1. Chapatti.

Nutritional characteristics of value added Chapatti

All three types of chapatti along with control chapatti, were oven dried to a constant weight at 60°C, ground to a fine powder in an electrical grinder and analyzed for various nutrients. Proximate composition including moisture, protein, fat,, ash and crude fibre was determined by standard methods [2]. Total, soluble and insoluble dietary fibre constituents were determined by the enzymatic method given by Furda [3]. Total minerals were determined according to the method of Lindsey et al. [4].

Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analysed in complete randomized design for analysis of variance, mean, standards deviation and critical difference according to the standard method [5].

Sensory characteristics of Chapatti

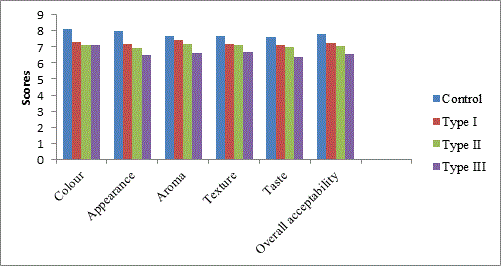

Results presented in Figure 1 indicated that the mean scores of wheat flour (control) chapatti were rated as ‘liked very much’ for all the organoleptic characteristics. The mean scores of control chapatti were 8.10, 8.0, 7.70, 7.60 and 7.82 for colour, appearance, aroma, texture, taste, and overall acceptability, respectively, which fell in category of ‘liked very much’. The scores of appearance and texture were similar i.e. 7.2 in Type-I chapatti whereas the scores for colour, aroma, taste and overall acceptability were 7.30, 7.10 and 7.24, respectively. In Type-III chapatti mean scores for colour, appearance, aroma, texture, taste and overall acceptability were 7.10, 6.50, 6.60, 6.70, 6.40 and 6.58, respectively, and fell in the category of ‘liked moderately’. It was observed that all types of chapattis were acceptable in terms of all sensory characteristics and the scores fell in category of ‘liked moderately’.

Figure 1. Mean scores of sensory characteristics of chapatti.

Nutritional evaluation of developed chapatti

Proximate composition of chapatti: Result of proximate composition found that wheat flour chapatti (control) had 7.60% moisture, 12.42% crude protein, 3.05% fat, 1.93% crude fibre and 1.58% ash, whereas Type-I chapatti contained 7.93% moisture, 13.85% crude protein, 5.34% fat, 2.23% crude fibre, and 1.58% ash. Type II chapatti prepared by 40% amaranth flour had 8.20, 14.28, 7.30, 3.17 and 1.75 per cent moisture, crude protein, fat, crude fibre and ash, respectively, whereas Type III chapatti prepared with 60% amaranth flour had 8.36, 18.23, 9.42, 4.26 and 1.81% moisture, crude protein, fat, crude fiber and ash, respectively. It is evident from the Table 2 that incorporation of amaranth flour to the control chapatti increased the amount of crude protein, fat and crude fibre significantly in all types of chapatti. Further, it was observed that addition of 20% amaranth flour to wheat flour (Type I chapatti) did not bring any change in its ash content whereas addition of 40% (Type II) and 60% (Type III) amaranth flour significantly increased ash content from 1.58 (control chapatti) to 1.75 and 1.81%, respectively.

| Types of chapatti | Moisture | Crude protein | Fat | Crude fibre | Ash |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (WF::100%) | 7.60 ± 0.11 | 12.42 ± 0.12 | 3.05 ± 0.02 | 1.93 ± 0.04 | 1.58 ± 0.07 |

| Type I (WF: AF::80:20) | 7.93 ± 0.08 | 13.85 ± 0.14 | 5.34 ± 0.06 | 2.23 ± 0.04 | 1.58 ± 0.03 |

| Type II(WF:AF::60:40) | 8.20 ± 0.05 | 14.28 ± 0.14 | 7.30 ± 0.01 | 3.17 ± 0.03 | 1.75 ± 0.01 |

| Type III(WF:AF::40:60) | 8.36 ± 0.12 | 18.23 ± 0.14 | 9.42 ± 0.06 | 4.26 ± 0.02 | 1.81 ± 0.03 |

| CD (P=0.05) | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.14 | 1.29 | 0.09 |

| Note: Values are mean ± SE of three independent determinations; WF=Wheat Flour; AF=Amaranth Flour | |||||

Table 2: Proximate composition of Chapatti (%).

Dietary fibre: Total dietary fibre content of control chapatti was 4.80% and that of Type I, II and III chapattis were 11.13, 19.70 and 22.06%, respectively. The total dietary fibre content of all three types of chapattis differed significantly from each other as well as from control chapatti. Similar trend was observed in insoluble and soluble dietary fibre content of control and amaranth flour incorporated chapattis. With the increase of incorporation level of amaranth flour in chapattis, the amount of total dietary fibre, insoluble and soluble dietary fibre increased significantly. The insoluble and soluble dietary fibre contents of control chapatti were 3.90 and 0.90, respectively, which increased to 13.83 and 8.23%, respectively, with the incorporation of 60% amaranth flour (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Dietary fibre content of chapatti.

Minerals: The results of mineral content of chapattis are presented in Table 3. Total calcium content of control chapatti was 55.59 mg/100 g which was doubled in Type I chapatti (112.44 mg/100 g) after addition of 20% amaranth flour. Similarly calcium content increased to more than three times (187.07 mg/100 g) and four times (222.70 mg/100 g) after incorporation of 40% and 60% amaranth flour, respectively. The zinc content of control chapatti was 2.22 mg/100 g. A significant increase in zinc content to 2.40, 2.52 and 2.73 mg/100 g in type I, type II and type III chapatti was observed, respectively, after incorporation of amaranth flour to wheat flour. Though with the increase of incorporation level of amaranth flour in the chapattis, there was a significant increase in zinc content over the control values but the extent of increase was not as that of calcium. The iron content of control chapatti was 4.43 mg/100 g which increased to 6.71 mg/100 g after 20% incorporation of amaranth flour, to 8.77 mg/100 g after 40% incorporation and 10.62 mg/100 g after 60% incorporation of amaranth flour. All the three types of chapattis differed significantly among themselves as well as from control chapatti for their iron content. The potassium content of wheat flour chapatti (control) was 301.08 mg/100 g which subsequently increased to 361.66, 392.83 and 418.91 mg/100 g after incorporation of 20%, 40% and 60% amaranth flour, respectively.

| Product | Total minerals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chapatti | Calcium | Zinc | Iron | Potassium |

| Control (WF:: 100%) | 55.59 ± 0.02 | 2.22 ± 0.01 | 4.43 ± 0.10 | 301.08 ± 4.47 |

| Type I (WF: AF::80:20) | 112.44 ± 0.01 | 2.40 ± 0.01 | 6.71 ± 0.07 | 361.66 ± 7.43 |

| Type II (WF: AF::60:40) | 187.07 ± 0.02 | 2.52 ± 0.02 | 8.77 ± 0.07 | 392.83 ± 4.98 |

| Type III (WF: AF::40:60) | 222.70 ± 0.05 | 2.73 ± 0.01 | 10.62 ± 0.05 | 418.91 ± 5.05 |

| CD (P=0.05) | 1.88 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 18.55 |

| Note: Values are mean ± SE of three independent determinations, WF=Wheat Flour; AF=Amaranth Flour | ||||

Table 3: Total mineral content of chapatti (mg/100 g, dry weight basis).

The available calcium content in control chapatti was 16.43 mg/100 g (Table 4). A significant increase in available calcium content to 20.69, 47.67 and 59.96 mg/100 g in Type I, Type II and Type III chapatti was observed, respectively, after incorporation of 20%, 40% and 60% amaranth flour to wheat flour. The available iron content of control chapatti was 0.63 mg/100 g, which increased up to 1.10 mg/100 g with incorporation of 60% amaranth flour (Type III). Type I and Type II chapatti contained 0.68 and 0.77 mg/100 g of available iron, respectively. Available iron content of Type I chapatti was almost equal to that of control chapatti.

| Product | Available minerals | |

|---|---|---|

| Â Chapatti | Available calcium | Available iron |

| Control (WF:: 100%) | 16.43 ± 0.15 | 0.63 ± 0.03 |

| Type I (WF: AF::80:20) | 20.69 ± 0.08 | 0.68 ± 0.02 |

| Type II (WF: AF::60:40) | 47.67 ± 0.04 | 0.77 ± 0.01 |

| Type III (WF: AF::40:60) | 59.96 ± 0.07 | 1.10 ± 0.06 |

| CD (P=0.05) | 1.78 | 0.1 |

| Note: Values are mean ± SE of three independent determinations, WF=Wheat Flour; AF=Amaranth Flour | ||

Table 4: Available calcium and iron content of Chapatti (mg/100 g, dry weight basis).

On the basis of sensory characteristics it was observed that chapatti upto 60% level of amaranth flour was acceptable. Lemos et al. demonstrated that it is possible to incorporate 10% whole amaranth flour in cheese bread while retaining product colour, flavour, and overall acceptability [6]. The sample containing 10% amaranth showed higher acceptability in terms of texture. Tomoskozi et al. observed that the substitution of wheat flour by amaranth and/or quinoa seeds flours results in the changes in rheological properties of dough and test bread quality parameters (volume, crumb firmness) [7]. The addition of 30% and above causes important quality deterioration in comparison to wheat bread. Amaranth flour was used in the manufacturing of bread by replacing 10, 15, 20 and 25% of wheat flour [8]. Bressani manufactured bread by blending 30% of amaranth and 70% of wheat [9].

It was observed that addition of 20% amaranth flour to wheat flour (Type I chapatti) did not bring any change in its ash content, whereas addition of 40% (Type II) and 60% (Type III) amaranth flour significantly increased ash content from 1.58 (control chapatti) to 1.75 and 1.81%, respectively. Blending of amaranth grain flours to cereal flours improved the protein quality of the product [10]. The use of 40% whole amaranth flour in the formulation of bread provided significant higher amounts of dietary fiber, proteins and lipids showing increases of 2.1, 2.0 and 1.1 g/100 g d.m., respectively [11].

The insoluble and soluble dietary fibre contents of control chapatti were 3.90 and 0.90%, respectively, which increased to 13.83 and 8.23%, respectively, with the incorporation of 60% amaranth flour. Martinez et al. demonstrated that substitution of bread wheat flour for whole meal amaranth flour up to a level of 30% significantly improved protein and dietary fibre contents, reaching an increase of 23 and 50% with regard to control sample, respectively [12]. Lemos et al. found that incorporation of 10% amaranth resulted in an increase of 18 times the amount of dietary fibre compared to the control [6]. Chauhan et al. showed that amaranth flour cookies had higher amount of total dietary fibre, followed by wheat flour cookies and raw amaranth flour cookies, respectively [13].

Total calcium content of control chapatti was 55.59 mg/100 g which was doubled in Type I chapatti (112.44 mg/100 g) after addition of 20% amaranth flour. Similarly calcium content increased to more than three times (187.07 mg/100 g) and four times (222.70 mg/100 g) after incorporation of 40% and 60% amaranth flour, respectively. The incorporation of 10% amaranth in formulation of cheese bread increased triple the amount of iron compared to the control [6]. It was established that zinc, calcium and iron contents of bread increased as amount of amaranth substitution increased [14].

Amaranth, a pseudo cereal rich in nutrients can be utilized in preparation of traditional products like chapatti. The results of the study indicated that amaranth can replace the staple cereal wheat up to 60% in chapatti to increase its nutritive value. Overall it is inferred that amaranth can be utilized in preparation of various traditional and snack products to enhance their nutritive value. The study demonstrated that grain amaranth has potential to contribute to the alleviation of dietary nutritional deficiencies.

I am extremely grateful to my advisor Dr. Darshan Punia and Department of Foods and Nutrition, CCS HAU, Hisar, Haryana for providing all facilities related to my research work.

Citation: Singh A, Punia D (2021) Influence of Addition of Different Levels of Amaranth Grain Flour on Chapatti. J Nutr Food Sci. 11:789.

Received: 22-Jan-2021 Accepted: 05-Feb-2021 Published: 12-Feb-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2155-9600.21.11.1000789

Copyright: © 2021 Singh A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.