Journal of Women's Health Care

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0420

ISSN: 2167-0420

Research Article - (2022)Volume 11, Issue 1

Introduction: Antenatal care is a type of care given for women during pregnancy and is a key strategy for reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The goal of Antenatal care is to prevent health problems of pregnant women through detection of complications and treatment of pregnancy related illness. Objective: This study aims to Assessment late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among antenatal care attendants in Governmental Health Centers of Harar Town, Ethiopia March 05 – 20/2020. Methodology: A quantitative cross-sectional institution based study was used to assess late initiation of antenatal care and factors associated with it in Governmental Health Centers of Harar Town. The sampling technique was Systematic random sampling method was used. Two hundred Seven pregnant women who attend ANC were included in this study. Data was entered, coded and analyzed using SPSS, version 20. Descriptive statistics like frequencies and percentages was used to present the result. Result: Out of 207 pregnant mothers included in this study, 136 (65.7%) pregnant mothers started their first ANC visit early while the remaining 71 (34. %) pregnant mothers started ANC late. Multivariate analysis revealed that Age, Gravidity and Waiting time were associated with independent variable. Those women whose age group 20- 25 years were 3 times more likely having early booking than those age group less than 20 years (AOR=3.374,95% CI=[1.117-10.189] women who had gave live birth were 2 times more likely having early booking than those women who had a history of child death(AOR=2.686,95% CI=[1.005-7.178] Those women had waited time of 1:30-2hours before having the service were 18% less likely having early booking than those women who had waited for less than 30minute (AOR=0.082,95%CI: 0.007-1.019) Conclusion: The results of this study indicated that two-third of the respondents had started their ANC within the recommended time (65.7%) and the rest one-third were booked late (34.3%). The Respondents educational level, knowledge on the importance of ANC service utilization, Source of the information which contributed to book timely for the current pregnancy and the advice given on the time of first ANC booking are significantly and positively influenced early initiation of ANC in Harar.

Antenatal care, Late initiation, Timely booking, pregnancy and Harar

Antenatal care is one of the key strategies for reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality directly through detection and treatment of pregnancy related illnesses, or indirectly through detection of women at risk of complications of delivery and ensuring that they could be deliver in a suitably equipped facility [1].

Consequently, pregnant women are missing the intended benefits of ANC which include early identification and management of pre-existing health conditions and complications of pregnancy to prevent life-threatening maternal and neonatal condition. Thus, late antenatal attendance makes difficult to implement effectively the routine ANC strategies that enhance maternal wellbeing and good prenatal outcomes. In this regard, the identification of factors associated with late ANC attendance is a major public health objective which could help come up with strategies that could improve the quality ANC service provision and timing of first ANC attendance [2].

Globally, the total number of maternal deaths de-creased by 45% from 523 000 in 1990 to 289 000 in 2013. Similarly, global MMR

declined by 45% from 380 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births

in 1990 to 210 in 2013 yielding an average annual decline of 2.6%. Developing countries account for 99% (286 000) of the global maternal deaths with sub-Saharan Africa region alone accounting for 62% (179 000) [3].

Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality have continued to be a major problem in developing countries despite several efforts were made to reverse the trend. Sub-Saharan Africa is still the riskiest region in the world for dying of complications in pregnancy and childbirth [4].

Ethiopia is one of the countries with high maternal mortality. The MMR was 990 per 100,000 in the year 2000; it was 740 per 100,000 live births in 2005 and 420 per 100,000 in 2013.According to the systematic review made on antenatal care as a means of increasing birth in the health facility and reducing maternal mortality, the minimum antenatal care visits recommended by WHO (4 visits) was possible only for less than about one-third of the pregnant women in some SSA countries like Niger (15%), Ethiopia (19%), Chad (23%), Burundi (33%), Mali and Rwanda (35% each) [5-9].

Low prenatal coverage, few visits, and late booking are common problems throughout SSA posing difficulty in accomplishing the WHO recommendation. Despite to this, the EDHS 2014 report indicated that, about four in every ten Ethiopian women (43%) did not receive any antenatal care for their last birth in the five years preceding the survey. Seventeen percent of women made their first ANC visit before the fourth month of pregnancy where urban women made their first ANC visit more than a month earlier than rural women. The report revealed that there is still high prevalence of late ANC initiation in both urban and rural settings of the country [10].

Focused ANC (Antenatal Care) contributes to good pregnancy outcomes. Benefits of FANC (Focused Antenatal Care) in influencing outcomes of pregnancy depend to a large extent on the timing and quality of FANC. FANC consists of early start of ANC with the first antenatal visit in the first trimester, followed by the second visit in the second trimester and two visits in the third trimester if the woman does not have any problem [11]. Women who initiate ANC late miss out these intended benefits of FANC and encounter negative effects like lack of proper information and late identification and management of life threatening maternal and neonatal conditions. Late ANC is when a pregnant woman book for ANC after 12 weeks of pregnancy [12].

Timely and adequate antennal care is generally accepted to the effective method of preventing adverse out comes in pregnant women and their babies. Several studies have showed an association between the late gestational ages at the initiation of ANC and adverse maternal and infant out comes. Therefore, this study is aimed at examining factors associated with late ANC attendance amongst pregnant women’s at Harar Governmental Health Center.

A cross - sectional study in Durban, South Africa indicated that 23.4% were “early bookers” 47.9 were “late bookers” and 28.7% were “un-booked” for ANC. The Majority of women presented for formal “booking” late in pregnancy 47.9% booked at gestational age of six months after the last menstrual period [13].

A Cross Sectional study conducted at Mekelle city indicated that 48% made their first visit in their first trimesters, and 42.4% in their second trimester of pregnancy and only 1.8% of women attended antenatal care in their third trimester of pregnancy [14]. Similarly, cross sectional study on timing of first Antenatal care booking at public health institutions in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, reported that, the proportion of respondents who made their first ANC visit within the recommended time (before or at 12 weeks of gestation) is 246 (40.2%) while those who booked late (after 12 weeks of gestation) were 366 (59.8%). The timing of first ANC booking ranges from 1st month to 9th months of gestation.

A cross sectional study conducted on timing of first Antenatal care booking at public health institutions in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, reported that, out of 612 pregnant woman attending ANC, the majority of them (440 Pregnant women) were in the age group of 20–29. Out of these 184 (42 %) were booked within time (12 weeks of gestation and before) and the rest 256 (58%) booked late (After 12 weeks of gestation) [15].

The study conducted at Kembata-Tembaro Zone in Southern Ethiopia, in public health centers, indicated that, the prevalence of late entry to antenatal care was 68.6%. On this study multivariate analysis revealed that age, maternal education, family income, parity, previous utilization of antenatal care and type of pregnancy remained significant factors influencing late booking. The findings of this study showed that most women book antenatal care late.

The reviewed literatures reported that, socio-demographic variables like maternal age, marital status, maternal education, occupation, ethnicity, religion, family income, residence, accessibility of service were found to be predictors that either positive or negative influence on timing of ANC booking. In addition to these obstetrics history, past and current experience of service utilization and awareness of care and pregnancy related complications have also similar influence on ANC booking [16].

Study Area and Period

The study was in Harari Regional State, which is located at the Eastern parts of Ethiopia. It found 526kms away from Addis Ababa, which is the capital city of Ethiopia. According to the Harari Regional State Health Bureau Annual Report 2017, there are 3 governmental and 2 private Hospitals, 8 Health Center, 27 Community Health Posts and 1 Regional laboratory found in the town [17].

Currently the status might be the same, and health center facilities were preferred because they are the first level of care facilities and mainly engaged in preventive health services. Whereas, hospitals are providing services to those clients referred from other settings, when complications arise and detected by skilled providers. Hence, the first ANC booking takes place in health centers. Most mothers follow their antenatal checkups at governmental health centers since the service is given free of charge. The study will have conducted from March 05 – 20/2020 [18].

Study Design

A quantitative cross-sectional institution based study was conducted.

Variables of the Study

Dependent Variable

Late ANC initiation.

Independent Variable

• Predisposing Factors(Sociodemographic)

• Enabling Factors(Obstetrics)

• Need Factors(other)

The Source and Study Population

Source Population

All pregnant women who came to attend ANC at a Governmental Health Centers of Harar Town [19].

Study Population

Pregnant women who attended ANC at Governmental Health centers in Harar town, during the study period [20].

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria: Pregnant mothers who are attending 1st ANC visit and above [21].

Exclusion Criteria

Pregnant women who are not willing full to participate and who are seriously ill [22]

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Technique

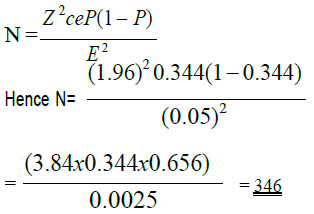

The sample size was estimated using sample size determination formula for a single population proportion formula. The previous studies done in Addis Ababa reported that the prevalence of late initiation of ANC was 34.4% (44). Therefore, the total sample size was calculated with the marginal error of 0.05, with 95% confidence interval. Based on these assumptions, a total sample size was calculated using the formula as indicated below [23].

Therefore, (p = 0.344) Level of significance to be 5% (α = 0.05), Z

α/2 = 1.96 Using Correction Formulas Sampling Size was

N = n/n+1/N

= 346/ 346+1/516

N= 207

With the above inputs using correction formula the sample size was 207.

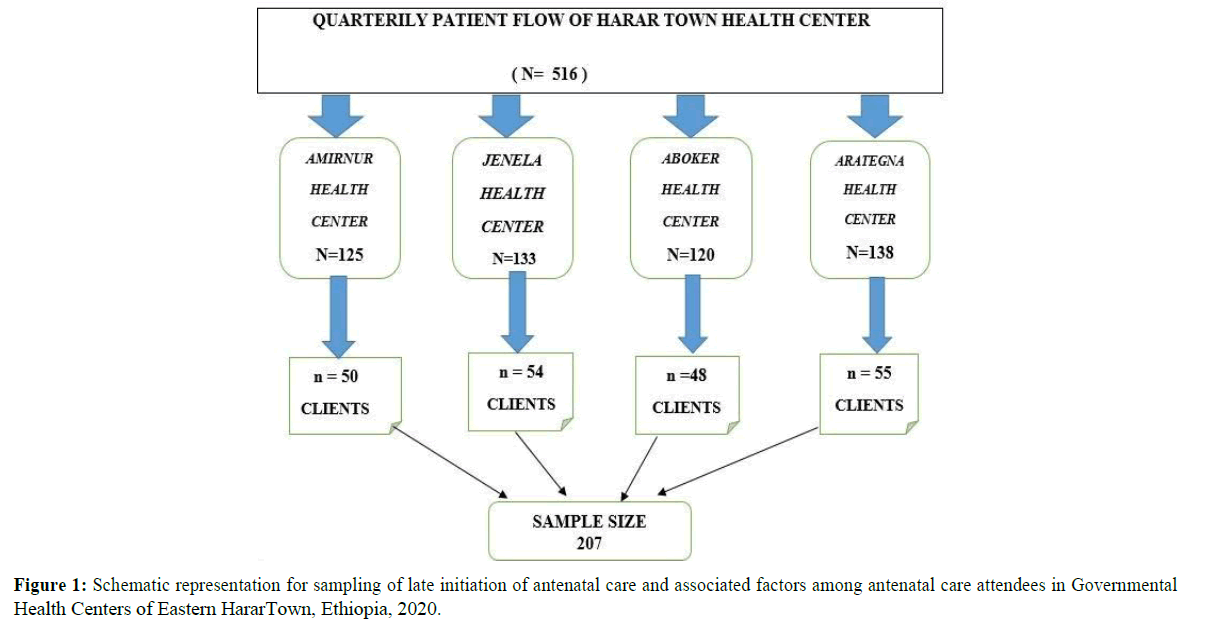

Sampling Techniques

By using the flow of the pregnant woman visiting ANC in the previous 12 months as a base line there were a total of 2062 pregnant women in were visit the health centers, in Four health centers Quarter flow of the of the client was 516 clients and sample size allocated proportionately based on of client flow in each health center, for Arteaga=55 Client, Jenela = 54 Client, Aboker = 48 client, Amir Nur = 50 client. The list of governmental health centers is indicated in Figure 1, who fulfills the eligibility criteria during the study period [24].

Figure 1. Schematic representation for sampling of late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among antenatal care attendees in Governmental Health Centers of Eastern HararTown, Ethiopia, 2020.

Data Collection Procedure and Instrument

The data was collected by interviewing the pregnant women after getting informed consent. Health professional Five BSc holder, who are not working in the health centers was participated in data collection after being given an intensive two days training on the data collection tools and collection procedures by the principal investigator. Data was collected by using semi structured and pre-tested questionnaire. The questionnaire included questions on socio de-mographic characteristics, obstetric factors etc [25]. The questionnaire was originally being developed in English and then translated into Amharic. It was translated back to English by another person to ensure its consistency. Most of the items will be adapted from existing literatures [26]. The Amharic and Afan Oromo language questionnaire was used to collect data at all health

centers during the study period. Supervision of data collectors was made two times at each health centers during the study period by the principal investigator and supervisors [27].

Data Quality Assurance

Pretesting of the questionnaire was conducted on pregnant women attending ANC at governmental Sofii health center before the study period and appropriate modification was applied. Administration of pre-test among 5% of the total sample. All filled questionnaires were checked for completeness, accuracy, and consistency. Necessary corrections and changes were made. All supervision was carried out by the Principal Investigator throughout the data collection period. This helped to identify problems that had addressed on the questionnaires [28].

Data Processing and Analysis

The collected data was carefully checked for completeness as well as consistency. Any confusion on the data collection procedure and/ or response. Data was entered, coded and analyzed using SPSS, version 20. Descriptive statistics like frequencies and percentages was used to present the categorical independent variables, and mean/standard deviation was used to describe a continuous variable. Frequency Tables 1-7 were used to present descriptive results. For this study, bivariate logistic regression model was fitted as a primary method of analysis. Odds ratios (OR) was computed with the 95% confidence interval (CI) to see the Late ANC time of initiation in relation to the considered associated factors in this research. Independent factors, with a P-value < 0.2 obtained in the bivariate logistic regression were entered into the multiple logistic regression models. Then an adjusted odd ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval was calculated for the significant predictive variables, and statistical significance was accepted at (P< 0.05). Logistic regression was also used to present the results [29].

| Variables | Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | ||

| <20 years | 34 | 16.40% | |

| Age in years | 20-25 years | 72 | 34.80% |

| 26-30 years | 78 | 37.70% | |

| >30 years | 23 | 11.10% | |

| Amara | 73 | 35.30% | |

| Oromo | 103 | 49.70% | |

| Ethnic group | Guragie | 31 | 15% |

| Religion | Orthodox | 84 | 40.60% |

| Muslim | 100 | 48.30% | |

| Protestant | 23 | 11.10% | |

| Single | 7 | 3.40% | |

| Marital status | Married | 192 | 92.80% |

| Divorce | 8 | 3.90% | |

| Illiterate | 36 | 17.40% | |

| Educational level | Elementary School | 64 | 30.90% |

| High School | 43 | 20.80% | |

| Diploma & above | 64 | 30.90% | |

| Employed | 71 | 34.30% | |

| Occupation | Self employed | 82 | 39.60% |

| House wife | 54 | 26.10% | |

| Household income per month | < 1000 Birr | 32 | 15.50% |

| 1000 – 2000 Birr | 82 | 39.60% | |

| > 2000 Birr | 93 | 44.90% | |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents by timing of first ANC visit at selected heath centers, Harar Ethiopia, 2020.

| Variables | Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Gravida | Alive baby | 136 | 65.70% |

| Child die | 71 | 34.30% | |

| Had history of abortion | Yes | 32 | 37.20% |

| No | 175 | 62.80% | |

| Type of abortion | No abortion | 28 | 13.55% |

| Spontaneous | 4 | 1.90% | |

| Had history of child death | Yes | 71 | 34.30% |

| No | 136 | 65.70% | |

Table 2: Obstetric history of respondents and timing.

| Variables | Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Perception on importance of ANC for both the mother& the fetus | Highly important | 163 | 78.70% |

| Medium | 43 | 20.80% | |

| Less | 1 | 0.50% | |

| Perception on number of ANC visits per pregnancy | One visit | 163 | 78.80% |

| Two to three visits | 43 | 20.80% | |

| Four to six visits | 1 | 0.50% | |

Table 3: Perception on ANC service utilization by timing of first ANC booking at selected health centers, Harar Ethiopia, 2020.

| Variables | Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Previous experience of ANC preceding the current | Yes | 201 | 97.10% |

| No | 6 | 2.90% | |

| Waiting time for the previous pregnancy preceding the current (1st visit) | < 30 minute | 70 | 33.80% |

| 30 – 60 minute | 50 | 24.20% | |

| 1 hr. – 1:30 minute | 61 | 29.50% | |

| 1:30 – 2hr | 26 | 12.6%% | |

| Payments required for ANC service | Yes | 184 | 88.90% |

| No | 23 | 11.10% | |

Table 4: Past history of ANC service utilization by timing of first ANC booking at selected health centers, Harar Ethiopia, 2020.

| Variables | Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Means to confirm pregnancy | By examination (Urine) | 23 | 11.10% |

| Missed period one and more months | 129 | 62.30% | |

| Physiological change | 55 | 26.60% | |

| Your Husband | 165 | 79.70% | |

| Your Mother | 22 | 10.60% | |

| To whom pregnancy was reported first | Your Sister | 13 | 6.30% |

| Your Friend | 7 | 3.40% | |

| Is the current pregnancy planned | Yes | 200 | 96.60% |

| No | 7 | 3.40% | |

| If the pregnancy planned, did the plan include your husband | Yes | 199 | 96.10% |

| No | 8 | 3.90% | |

| If the pregnancy unplanned is that wanted by you after conception | Yes | 202 | 97.60% |

| No | 5 | 2.40% | |

| If the pregnancy unplanned is that wanted by your husband after conception | Yes | 202 | 97.60% |

| No | 5 | 2.40% | |

| Have you wanted abortion | Yes | 13 | 6.30% |

| No | 194 | 93.70% | |

Table 5: History of current pregnancy by timing of first ANC booking at selected health centers, Harar Ethiopia, 2020.

| Variables | Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Advise received on ANC for the current pregnancy | Yes | 191 | 92.30% |

| No | 16 | 7.70% | |

| Health care provider | 148 | 71.50% | |

| From whom advice received | Media (Radio, TV and the like) | 28 | 13.50% |

| Husband | 15 | 7.20% | |

| Did the advice include time of | Yes | 174 | 84.10% |

| Booking | No | 17 | 8.20% |

| Before 12 weeks of gestation | 136 | 65.70% | |

| Advise time | After 12 weeks of gestation | 71 | 34.30% |

| Perceived it is appropriate time | 111 | 53.60% | |

| Reason for booking for the current pregnancy | From my previous experience | 73 | 35.30% |

| Because of unplanned pregnancy | 23 | 11.10% | |

Table 6: History of current ANC visit by timing of first ANC booking at selected health centers, Harar Ethiopia, 2020.

| Characteristics | Booking Time) | P –value | Crude OR (95%) CI | P - value | Adjusted OR (95%) CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) | No (%) | |||||

| (befor12 weeks of Gestation | After12 weeks of Gestation | |||||

| 26-30 years | 55 (40.4%) | 23 (40.2%) | 0.518 | 1.359 | 0.37 | 1.649 [0.553 – 4.915] |

| >30 years | 13 (9.6%) | 13 (9.2%) | 0.116 | 2.5 | 0.44 | 1.726 [ 0.431 – 6.904] |

| Ethnic group | ||||||

| Amara | 45 (33.1%) | 28 (39.4%) | 0.281 | 0.66 | 0.719 | 1 |

| Oromo | 73 (53.7%) | 30 (42.3%) | 0.2 | 1.161 | 0.469 | 0.748 [ 0.341 – 1.641] |

| Guragie | 18 (13.2%) | 13 (18.3%) | 0.733 | 0.622 | 0.989 | 1.008 [0.340 – 2.991] |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 7 (5.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.3 | 1 | 0.942 | 1 |

| Married | 126 (92.6%) | 66 (93%) | 0.999 | 0 | 0.999 | 2.707[0.602 -12.178] |

| Divorce | 3 (2.2%) | 5 (7%) | 0.121 | 0.314 | 0.729 | 3.761[0.434 -32.576] |

| 1.420[0.476 -2.686] | ||||||

| Educational level | ||||||

| illiterate | 28 (20.6%) | 8 (11.3%) | 0.237 | 1 | 0.256 | 1 |

| Elementary School | 39 (28.7%) | 25 (35.2%) | 0.089 | 2.244 | 0.957 | 0.963[0.245 – 3.790] |

| High School | 25 (18.4%) | 18 (25.4%) | 0.068 | 2.52 | 0.413 | 1.628[0.506 – 5.231] |

| Diploma and above | 44 (32.4%) | 20 (28.2%) | 0.337 | 1.591 | 0.1 | 2.715[0.827 – 8.920] |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Employed | 50 (36.8%) | 21 (29.6%) | 0.43 | 1 | 0.57 | 1 |

| Self employed | 54 (39.7%) | 28(39.4%) | 0.546 | 1.235 | 0.507 | 1.411 [0.511 – 3.900] |

| House wife | 32 (23.5%) | 22 (31%) | 0.195 | 1.637 | 0.289 | 1.852 [0.592 – 5.788] |

| Household income per month | ||||||

| < 1000 Birr | 22 (16.2%) | 10(14.1%) | 0.201 | 1.558 | 0.687 | 1 |

| 1000 – 2000 Birr | 48 (35.3%) | 34 (47.8%) | 0.316 | 0.9 | 0.565 | 0.688[0.192 – 2.464] |

| > 2000 Birr | 66 (48.5%) | 27 (38%) | 0.813 | 0.455 | 0.79 | 1.130[0.462 – 2.764] |

| Waiting time for the previous pregnancy preceding the current | ||||||

| < 30 minute | 49 (36.0%) | 21 (29.6%) | 0.177 | 1 | 0.259 | 1 |

| 30 – 60 minute | 34 (25.0%) | 16 (22.5%) | 0.034 | 0.367 | 0.375 | 1.598[0.56 – 4.501] |

| 1 hr. – 1:30 minute | 41 (30.1%) | 20 (28.2%) | 0.068 | 0.403 | 0.512 | 1.384[0.523 – 3.659] |

| 1:30 – 2hr | 12 (8.8%) | 14 (19.7%) | 0.069 | 0.418 | 0.049 | 0.082[0.007– 1.019] |

| Means to confirm pregnancy | ||||||

| By examination (Urine) | 11 (8.1%) | 12 (16.9%) | 0.825 | 1 | 0.052 | 1 |

| Missed period one and more months | 84(61.8%) | 45(63.4%) | 0.082 | 0.491 | 0.133 | 0.342[0.84 – 1.388] |

| Physiological change | 41(30.1%) | 14(19.7%) | 0.119 | 0.313 | 0.484 | 0.218[0.049 – 0.976] |

| From whom advice received | ||||||

| Health care provider | 96 (77.4%) | 52 (77.6%) | 0.876 | 1 | 0.933 | 1 |

| Media (Radio, TV and the like) | 19 (15.3%) | 9 (13.4%) | 0.16 | 0.874 | 0.71 | 0.821[0.29 – 2.322]** |

| Husband | 9 (7.3%) | 6 (9%) | 0.708 | 1.231 | 0.987 | 0.989[0.258 – 3.788] |

| Gravidity | ||||||

| Alive baby | 89(65.4) | 47(66.2) | 0.913 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Child death | 47(34.6) | 24(33.8) | 0.007 | 1.034 | 0.049 | 2.686[1.005 –7.578]* |

Table 7: Bivariate and Multivariate Analysis Association of factors with timely booking of first ANC at se-lected health centers of Harar, 2020.

Antenatal Attendance

Early antenatal care: - refers to initiation of antenatal care before 12 weeks of gestation [30].

Late antenatal care: - refers to pregnancy follow up at 12 week of gestation or more (12 week of gestation used as a reference point which is calculated from LNMP of woman).

Delay in ANC: women who came for ANC after 12thweeks of gestation. This reference is taken from the 1st last menstrual period of pregnancy [31].

Predisposing Factors: The socio-cultural characteristics of individuals that exist prior to their utilizing service (Maternal Age, Educational Status, Occupation, Marital Status, Ethnicity, Religion, Parity, Attitudes toward the care, how the pregnant valued the care, and Knowledge concerning and towards the service) [32].

Enabling Factors: The logistical aspects of obtaining care (distance from health institution, means and cost of transportation and financial source for care and other expenses) [33].

Need Factors: The most immediate cause of health service use, from functional and health problems that generate the need for health care services (Awareness of pregnancy, perceptions on the use of early seeking ANC, and any advice from significant others) [34].

Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

Out of 207 pregnant women totally included in this study 207 (100%) have responded to the interview. The majority of the study participants 78 (37.7%) were in the age group of 26 to 30years followed by the age group of 20-25 (34.8%). In the age group of less than 20 (16.4%) and above 30 years were (11.1%) age groups. The age group ranges from 26 to 30 years and the mean age of respondents was 25 years. Regarding the ethnic composition of the respondents, the highest were Oromo 103 (49.8%), followed by Amara 73 (35.3%). The lowest proportion of respondents is Guragie 31 (15%). Respondents of Muslim religion were the majority 100 (48.3%) and the lowest were Protestant 23(11.1%). One hundred nighty two out of 207 (92.8%) ANC attendees were married and live together with husband.

Timing of First ANC visit

Out of 207 pregnant mothers included in this study, 136 (65.7%) pregnant mothers started their first ANC visit early while the remaining 71(34.3%) pregnant mothers started ANC late in either second or third trimester.

Obstetric History and Timing of First ANC visits

Out of the total respondents were 136(65.7%) gave alive baby while the rest 71(34.3%) of the respondent had a history of child die. Among the respondent 175 (82.6%) had no history of abortion while the rest 32(15.4%) had History of at least one abortion. With regard to the types of abortions 28 (13.5%) had spontaneous abortion 4(1.9%) of the abortions were self-induced of first ANC visits at selected health centers, Harar Ethiopia, 2020.

Knowledge and Perception of Respondents on ANC Service Utilization

163 (78.7%) have knowledge on the importance of ANC for the health of the mother and fetus and rated as highly important while the rest 43(20.8%) rated as medium and very few respondents said as the ANC has less importance to the health of mother and fetus. Of those who One (0.5%) of respondents perceived that four and more ANC visits were necessary. On the contrary 206 (99.5%) of them perceived that less than four ANC visits were sufficient throughout the whole pregnancy period.

Past History of ANC Service Utilization of the Respondents

From 207 respondents who had history of previous pregnancy 201(97.1%) had experience of ANC for the pregnancy preceding the current. 70(33.8%) respondents who attended ANC for the pregnancy preceded the current reported that they spent less than 30 minute, 50(24.2%) spent 30-60 minute and 61(29.5%) spent greater than 1 hours for the first visit. Among those who had experience in ANC, 26(12.6%) of them reported that they paid for ultrasound and laboratory outside the health center for the service provided.

History of Current Pregnancy and Timing of First ANC visit

129(62.3%) respondents confirmed pregnancy when they missed one and more menses, 55(26.6%) confirmed their current pregnancy by other Physiological change, while 23(11.1%) confirmed their current pregnancy by urine test offered by health of all respondents, 165(79.7%) were first informed the pregnancy to their husbands. the rest 22 (10.6%), 13 (6.3%), and 7 (3.4%), inform to their mothers, sisters, and friends, respectively. Two hundred (96.6%) respondents reported that their pregnancies were planned while 7(3.4%) respondents reported that it was unplanned. Of 200 pregnant women who had a planned pregnancy, 199(96.3%) of them included their husband in the plan. Out of the 7(3.4%) unplanned pregnancies 5(2.4%) were unwanted by the women after conception and similarly 5(2.4%) cases were unwanted by their husbands. From the unwanted pregnancy 13(6.3) were wanted abortion.

History of Current ANC Utilization and Tim-ing of fist ANC visit

Among the respondents 191(92.3%) of them reported that they received advise on ANC use before first booking while 16 (7.7%) of them did not receive advise from anyone. Among the respondent 148 (71.5%) received advice from health care provider, 28 (13.5%) from media, and the rest 15(7.2%) from husbands. Majority 174 (84.1%) of the respondents reported that they were informed when to be booked and the rest 17(8.2%) reported that the advice did not include when to book ANC. Among the respondents who were informed when to be booked ANC, 345 (84.8%) were informed as the correct time is before 12 weeks of gestation and among which 136(65.7%) of them booked on the recommended time as per the advice while the rest 71(34.3%)were informed the correct time but booked late. With regard to the reason why they preferred that time to come for first ANC visit. Majority 111(53.6%) reported as they perceived it is appropriate time. Other respondents 73(35.3%), 23(11.1) reported that they perceived from previous experience of timing and unplanned pregnancy, respectively. In addition, very few of them reported financial constraints and other personal reasons. First ANC booking at selected health centers, Harar Ethiopia, 2020.

Association of Factors with Timely Booking of first ANC

This study revealed that there is a general im-provement in flirt time antenatal booking. The majority 136 (65.7) booked on the recommended time. On bivarte analysis waiting time and Gravidity were associated with independent variable while after controlling of the co-founder.by doing multivariate analysis Age, Gravidity and Waiting time were stasticaly Significant associated with independent variable. Those women whose age group 20-25 years were 3 times more likely having early booking than those age group less than 20 years (AOR=3.374,95% CI= [1.117- 10.189] women who had gave live birth were 2 times more likely having early booking than those women who had a history of child death (AOR=2.686,95% CI= (1.005-7.178) Those women had waited time of 1:30-2hours before having the service were 18% less likely having early booking than those women who had waited for less than 30minute. (AOR=0.082, 95%CI: 0.007- 1.019).

Prevalence of Late Initiation of ANC

Cross - sectional study conducted in Durban showed that 23.4% where early bookers While 47.9% were late bookers, Information that was gathered from this study showed that the prevalence of early antenatal Care attendance is higher. It showed that two-third (65.7%) of the respondents had started their ANC within the recommended time and the rest one-third (34.3%) were booked late; this difference could be due to difference in study populations and sample size [35].

The study conducted in Mekelle city, indicated that 48% and only 1.8% of women attended antenatal care in their third trimester of pregnancy. This study showed that (65.7%) made their first visit in their first trimester and 34.3% in their second and third trimester of pregnancy this difference could be due to difference in study populations and study area [36].

Another study conducted at public health institution in Addis Ababa the proportion of respondent who made their first ANC visit with in the recommended time (before or at 12 weeks of gestation) is 246 (40.2%) while those who booked late (after 12 weeks of gestation) were 366(59.8%.) the timing of first ANC booking ranges from 1st month to 9th month of gestation. This study showed that the proportion of respondant136 (65.7%) pregnant mothers started their first ANC visit early while the remaining 71 (34.3%) pregnant mothers started ANC late. In both cases, the timing of the first ANC booking ranged 4 weeks (1st month) from last men-strual period to 32 weeks (8th month) of gestation, this difference could be due to difference in study area, sample size and study population [37-40].

Factors Associated with Late Initiation of ANC

A study conducted at university of Gonder hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, indicated that, those having formal education were 1.06 time more likely to book earlier compared to those who cannot read and write AOR=1.06 CI=95% [1.03-7.61] [41-44]. Gonder hospital Study Showed that formal education had associated with early booking, but in our study Education status had no significantly associated this may be due to small sample size [45].

A study done on timing and factor associated with first antenatal care booking among preg-nant mother in Gonder town; North west Ethiopia, result of logestic regeration analysis showed that pregnant mother Aged 25 and below were nearly two times more likely to commence ANC AOR=2.85 CI=95% [1.10-3.09] with in the recommended time compare to their counter were in the age categories of 20 -29 years, representing 52.0% of the study population [46,47]. This study the result of logestic regeration analysis showed that pregnant mother Aged 20-25 years were three times more likely to commence ANC AOR=3.374 CI=95% [1.117- 10.189] with in the recommended time Compare to their counter were in the age categories of less than 20 years, representing 16.4% of the study populations.

The prevalence of late initiation on this study was 71 (34.3 %). Age 20 -25 years, Gravidity and waiting time were significantly associated with late intention. On this study majority of the study participant were start there ANC visit eerily which accounts 136 (65.7%). Late antenatal care attendance is currently progressive change in Harar due to the massive work done in maternity care.

Keeping in view of the present research study findings, the following recommendations have been made:

• Even the prevalence of late initiation of ANC visit on this study was large there is need to investigate more factors that con-tribute to the current late entry to ANC among women.

• Shorten client waiting time or providing the service as early as possible as it is encouraged early booking.

• There is a need to explore client-provider interactions in provision of ANC services in public MCH facilities. Such study will elucidate useful suggestions on improving, address provider needs and enhance client satisfaction

• Further the Regional health office and the health facilities should continue the current endeavor which emphasizes the maternal health through communication program highlighting the importance of the antenatal care on print and electronic channels of mass media.

• Other researcher should better to conduct this research with large sample size to ex-plore further knowledge.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Citation: Yezengaw TY (2022) Late Initiation of Antenatal Care and Associated Factors among Antenatal Care Attendees in governmental Health Centers of Harar Town, Ethiopia. J Women's Health Care 11:561.

Received: 03-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. JWH-22-15378; Editor assigned: 04-Jan-2022, Pre QC No. JWH-22-15378(PQ); Reviewed: 18-Jan-2022, QC No. JWH-22-15378; Revised: 21-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. JWH-22-15378(R); Published: 28-Jan-2022 , DOI: 10.35248/2167- 0420.22.11.561

Copyright: © 2022 Yezengaw TY, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.