Journal of Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-9570

ISSN: 2155-9570

Case Report - (2021)

We all have become slaves to our mobile phones for most of our daily activities which directly or indirectly has hazardous impact on our health and lives especially for vision. Although blast injuries are common with war, cooking gas and firecracker, but in last couple of years, mobile phone blast cases also popularly known as “BOMBILE” (Blast of Mobile Battery in Living Eye) are coming up which are time to time reported on internet and in scientific journals. We present a case series of 3 patients presented with phone battery explosion which highlights how this technology driven device created to make our lives easier can be a menace and why there is an urgent need to create awareness in society for their safe and proper handling.

Bombile; Mobile Phone; Eye sight; Visual acquity

In parallel with technological advancements, humankind encounters devices transforming chemical energy to electrical energy such as mobile phones [1]. Indiscriminate usage of mobile phones makes us vulnerable to the associated risks including accidental burns and blast injuries [2]. Although, sparsly reported, mobile phone blasts are increasing in recent times causing disastrous consequences. This increase can be attributed mainly to the usage of low quality products, user negligence and use of phone while on charging. Lithium-ion batteries, commonly used to power devices such as laptops, cell phones, smart watches, and e- cigarettes are known as explosion hazards [3,4]. Explosions involving smartphone batteries are sparsly reported in literature [3]. Through these cases, we draw attention to such injuries and consider how their incidence and severity may be reduced by appropriate safety measures.

Case 1 (C1) and case 2 (C2)

23 Year (C1) and 22 Year (C2) old sisters, college students, presented to emergency department after sustaining eye injuries due to mobile phone battery blast while using and charging the phone simultaneously. They had complaints of blurred vision, severe irritation bilaterally. On initial examination, eyes were covered with soot particles, lid edema and conjunctival congestion. Eye irrigation was done with copious amount of normal saline to remove all the soot particles there and then patients were taken for ophthalmic examination.

C1 had BCVA (Best Corrected Visual Acquity) of 20/200 RE (Right Eye) and 20/40 LE (Left Eye). On slit lamp examination, soot particles were present in both eyes, there was full thickness epithelial defect measuring 7 × 9 mm in RE and punctuate staining LE along with a few sub epithelial opacities. Evidence of limbal ichaemia in two clock hours with <30% of conjunctival involvement in RE and no limbal or conjunctival involvement was seen in LE, although bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva were congested bilaterally. Siedel’s test was negative, no evidence of corneal perforation or foreign body in Anterior Chamber. Patient was admitted in ophthalmology ward and was diagnosed as ocular surface burn grade 2 in RE and grade 1 in LE. RE was patched, and patient started on Tab Vit C, topical antibiotics and lubricant for both eyes and corticosteroids for RE in tapering doses.

On PAD 1 (Post Admission Day), BCVA in both eyes were same as previous day, while epithelial defect in RE was reduced to 3 × 2 mm, had sub epithelial opacities approx 8-10, limbal vessel blanching had disappeared and limbal vasculature was present 360 degrees, conjunctival involvement had also decreased with only mild congestion present. On LE, the cornea was clear of any epithelial staining, and was free of symptoms, no sub epithelial opacities and conjunctival congestion was present. Fundus was examined and revealed no abnormality.

Patient was discharged on PAD 3, with BCVA of 20/80 and 20/20 LE with a full course of topical antibiotics, tapering corticosteroids and lubricants.

On follow-up day 7, some of the opacities were reduced in size and thickness, BCVA was 20/40 in RE, visual prognosis was explained and 2 weekly follow-up advised for which she was lost.

C2 had milder symptoms, BCVA 20/40 LE and 20/20 RE. Punctuate staining in LE with 3 areas of corneal burns in the form of sub epithelial opacities in both visual axis and away were present, without any limbal or conjunctival involvement. RE was free of any corneal, limbal, conjunctival involvement, a mild congestion was seen on conjunctiva, rest of the ocular examination was within normal limits.

Patient was managed on OPD (Outpatient Department) basis with topical antibiotics, lubricant and decongestant. She was reassessed on next day, epithelial lesions were resolved, corneal burns were present, congestion reduced significantly and was explained about chronic nature and associated visual symptoms because of sub epithelial opacities. BCVA in LE remained 20/40 for a period of 2 weeks after which she was lost to follow up.

Case 3

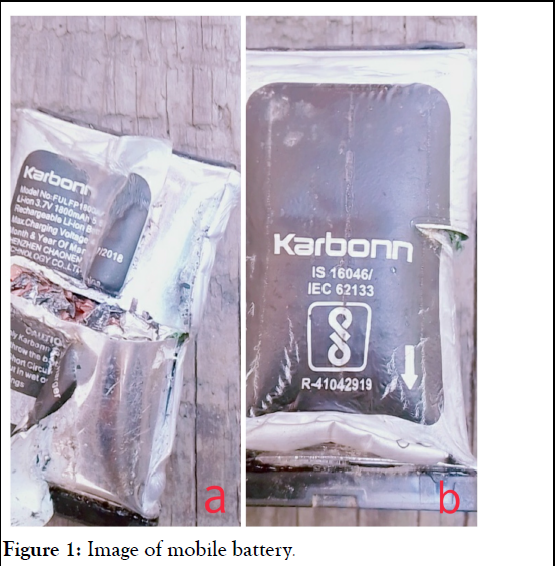

10 year old male child sustained eye injury in similar fashion as previously described as he was playing on mobile phone while it was being charged (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Image of mobile battery.

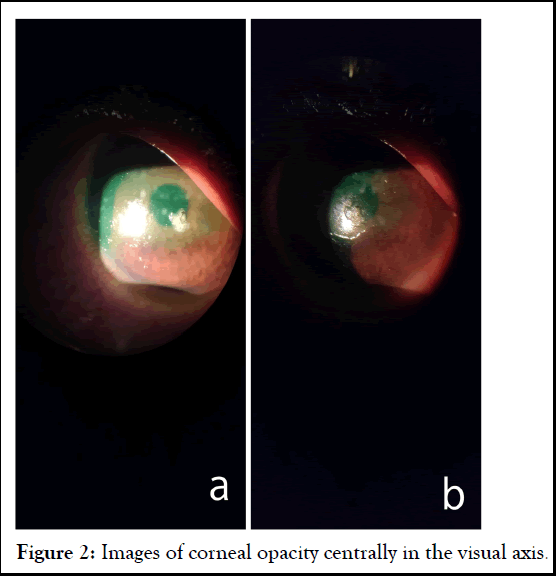

Parents took him to nearby primary health care center where his eyes were irrigated vigorously with saline, primary treatment with antibiotics was given and was referred to our center the very next day. On presentation, child’s RE was patched, he had complaints of burning sensations and pain in both eyes. As primary treatment, eye wash was done and then further evaluated for ophthalmic injury. BCVA in RE was 20/40, LE 20/20. In right eye, soot particle and corneal opacity were present centrally in the visual axis (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Images of corneal opacity centrally in the visual axis.

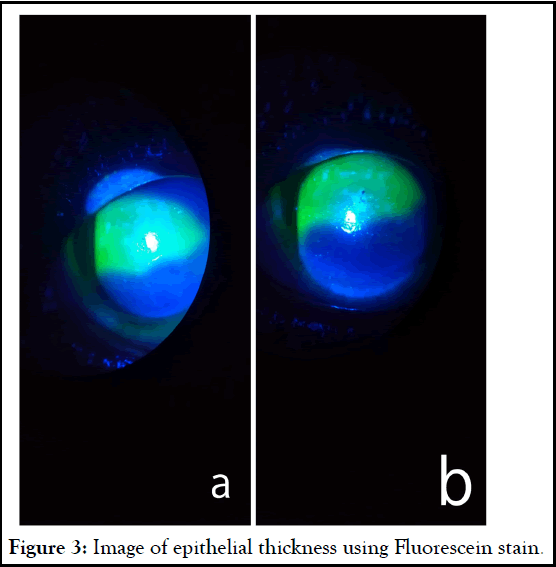

Fluorescein stain was assessed under cobalt blue filter, which revealed full thickness epithelial defect measuring around 7 × 4 mm (Figure 3), No evidence of limbal ischaemia or conjunctival involvement was seen clinically. LE was free of any signs of ocular involvement but patient had mild burning sensation in it. Patient was admitted, diagnosed with grade 1 ocular surface burn and started on topical antibiotic, lubricants and corticosteroids in tapering doses.

Figure 3: Image of epithelial thickness using Fluorescein stain.

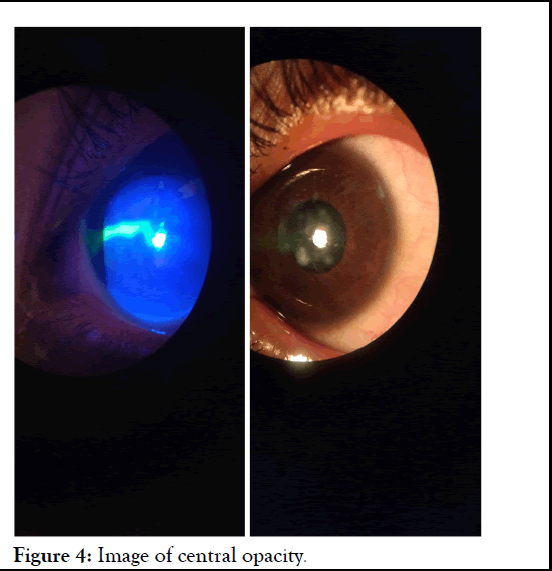

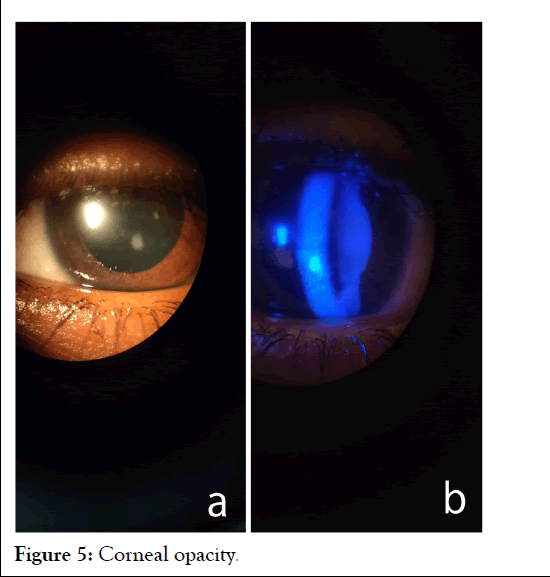

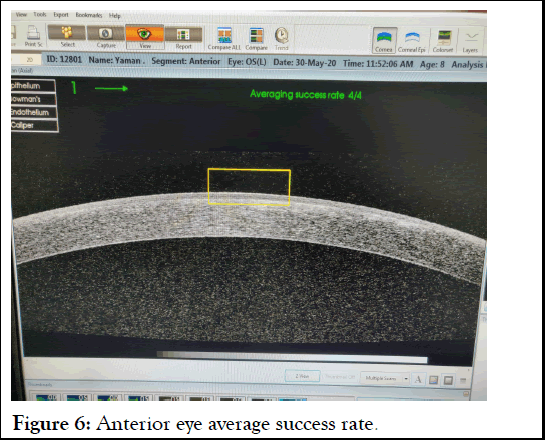

On the next day, epithelial defect had reduced significantly to 4 × 1 mm dimension, opacity was present centrally (Figure 4), Conjunctival congestion has disappeared, fundus was normal, no refractive error was found, AS-OCT was ordered which was within normal. Parents were counselled about the visual sequalae which can be caused due to central corneal opacity. Patient was discharged on day 3 (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 4: Image of central opacity.

Figure 5: Corneal opacity.

Figure 6: Anterior eye average success rate.

With BCVA of 20/40 RE under the cover of antibiotics, tapering steroids and lubricants. Attendants showed inability to come for follow ups, were advised to visit local hospital.

Lithium-ion batteries may overheat during charging leading to ‘HERMAL RUNAWAY’ an unregulated increase in internal battery temperature [3]. Inside the main line of defence against short circuiting is a thin and porous slip of polypropylene that keeps the electrodes from touching. If that separator is breached, the electrodes come in contact, the things get very hot very quickly. The batteries are also filled with a flammable electrolyte, one that can combust when it heats up, then really get going once oxygen hits it. Thus, the mechanism of injury from battery blasts could be a combination of mechanical (battery pieces, thermal and chemical injuries [4,5]. Zieker et al., reported a case about corneal injury due to watch battery explosion. Kumar A et al. published nonrelated cases; all cases presented with open globe injury when mobile phones exploded while charging. Patients were taken for repair surgeries but had severe ocular morbidsity with only up to perception of light [6,7]. Kumar et al. published a case of 15-year-old boy who sustained abdominal injury in the form of colonic perforation when he was using mobile phone while still on charging. Ohri et al. [8] presented a case of 15-year-old boy who sustained oral and ocular injuries due to phone battery blast while he was pulling out battery with his teeth [8,9].

Timely presentation and proper management of the ocular surface burns can salvage the vision. These cases signify the need to increase public awareness about the potential risks associated with cellphone use, to adopt safe practices as per recommendations from the manufacturers and to avoid counterfeit products, to avoid such accidents. One should remove the battery if handset gets wet and let your cell phone dry before you put it back, should not place cell phone in a hot car, should not use plastic cases to protect cell phone, they can overheat it, prefer original and authorized accessories, should not answer a call while it is being charged, never use the cell when it is hooked to the mains. We must be aware that it can also be an instrument of death [7].

Cataract surgery is indeed capable of inducing dry eye symptoms and signs. Therefore, prior to surgery, patients must be informed about the possible increase in dry eye symptoms, and if indicated, artificial tears may be prescribed in the postoperative period. Future research should focus on realistic modifications to the phacoemulsification procedure to achieve a safer approach in patients with ocular surface disorders. When dry eye is diagnosed pre operatively, surgeon should add topical preservative free lubricating drops and in exceptional circumstances topical cyclosporine drops. One should use ophthalmic viscosurgical devices (OVDs) on corneal surface during phacoemulsification cataract surgery to reduce the trauma induced by surgery and BSS irrigating solution flushing.

None

Citation: Sharda P, Panwar P (2021) ‘‘Bombile’’: A Newest Enemy to Our Sight? A Case Series. J Clin Exp Ophthalmol. S13:003.

Received: 13-Apr-2021 Accepted: 26-Apr-2021 Published: 03-May-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2155-9570.21.s13.003

Copyright: © 2021 Sharda P, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.