Clinical & Experimental Cardiology

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-9880

ISSN: 2155-9880

Mini Review - (2024)Volume 15, Issue 8

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is a chronic autoimmune disorder categorised into Crohn’s disease and IBD associated myocarditis. Extraintestinal Manifestations (EIMs) of IBD include rare and potentially fatal presentations like acute myocarditis, which may be complicated by acute inflammatory heart failure, cardiogenic shock and ventricular arrythmias. We reviewed the existing literature on myocarditis occurring as an EIM of IBD to identify populations at higher risk, evaluate cardiac outcomes and explore management. A literature review showed 27 cases of IBD related myocarditis and there were similar number of patients with Crohn’s Disease (CD) and Ulcerative Colitis (UC). IBD patients under 30 years of age, including paediatric patients, were more commonly affected. Diagnosis of IBD associated myocarditis occurred within 2 years of IBD diagnosis in 63% of patients, mostly during periods of intestinal disease activity. 37% manifested at the time of IBD diagnosis. Infliximab, a TNF-α inhibitor, may be an effective and safe therapeutic option for steroid refractory myocarditis in this high-risk patient group, who have worse cardiac outcomes compared to the general myocarditis population. Understanding of IL-1 mediated inflammation in the pathogenesis of IBD, EIMs and myocarditis is evolving. Although this may be an attractive therapeutic target, further research on its efficacy and safety in IBD and high-risk myocarditis is required.

Inflammatory bowel disease; Extraintestinal manifestations; Myocarditis; Infliximab; IL-1 inhibitors; Vedolizumab

IBD is a complex autoimmune disorder encompassing CD and UC characterised by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Disease course is characterised by periods of activity and quiescence, called flares and remission respectively. The pathogenesis of IBD is not fully understood; however, a complex interplay between genetic, environmental, gut epithelial, microbial and immune factors is central to disease onset [1]. EIMs refer to involvement of organs outside of the gastrointestinal tract, which may occur independent of IBD disease activity or preceding its diagnosis. These can affect up to 50% of IBD patients, causing considerable morbidity and infrequently, mortality [2].

Myocarditis is a potentially fatal EIM of IBD that may occur independent of disease activity. Although IBD patients have an increased risk of myocarditis [3], myocarditis occurring as an EIM is rare. Interestingly, studies have reported a higher prevalence of myocarditis in UC compared to CD [3,4]. Distinguishing myocarditis as an EIM of IBD from therapy related adverse effect and infectious causes presents a diagnostic challenge and has significant implications on patient care. Treatment often involves immunosuppression with steroids; however, there may be a role for biologic drugs commonly used in IBD. We aim to review existing literature on myocarditis occurring as an EIM in IBD, particularly evaluating the diagnostic approach, pathophysiology, evolving treatment paradigm and cardiac outcomes.

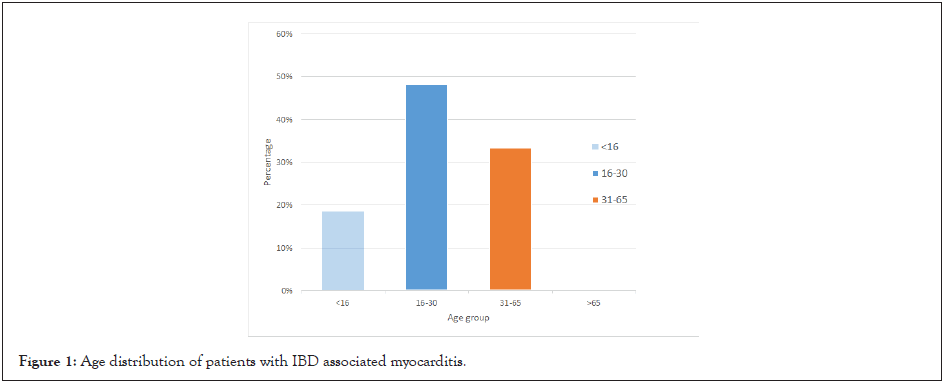

A review of literature identified 27 case reports of myocarditis occurring as an EIM of IBD. The mean age of myocarditis diagnosis was 28 years. 19% were paediatric patients under the age of 16 years and 67% of patients were 30 years or younger at myocarditis diagnosis. Cases were not reported in elderly IBD patients (>65 years), with the latest diagnosis being at 56 years. Interestingly, unlike previously reported, there was no significant tendency to affect either IBD phenotype as 44% of patients had UC and 56% had CD. However, males (67%) were affected more commonly than females (33%).

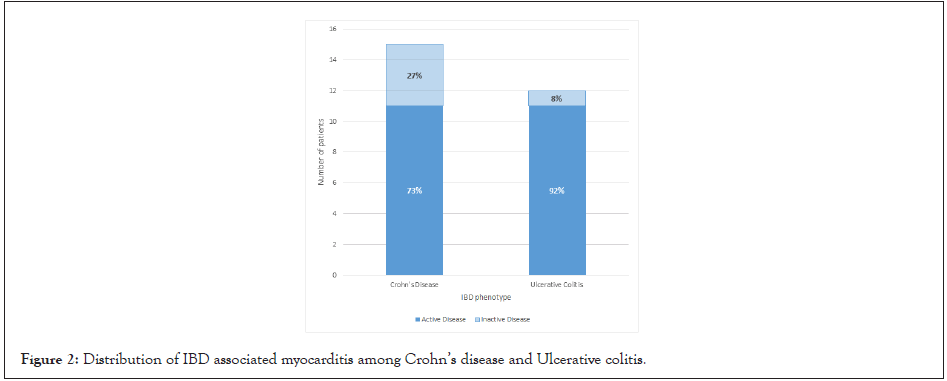

81% of myocarditis cases were reported in patients with active IBD. Among the 19% of patients with myocarditis during a period of disease inactivity, the majority (80%) occurred in CD patients. The low proportion of IBD related myocarditis occurring when luminal disease is quiescent likely reflects underreporting due to diagnostic challenges. The mean time of onset for myocarditis from IBD diagnosis was 3.88 years. Importantly, IBD related myocarditis may manifest before, simultaneous with or after an IBD diagnosis. 63% of patients who developed myocarditis were diagnosed within 2 years of IBD diagnosis and 37% manifested simultaneously with the IBD diagnosis. Among the 10 cases where cardiac MRI (cMRI) was performed, 50% had at least one atypical radiological finding, most commonly delayed subendocardial enhancement.

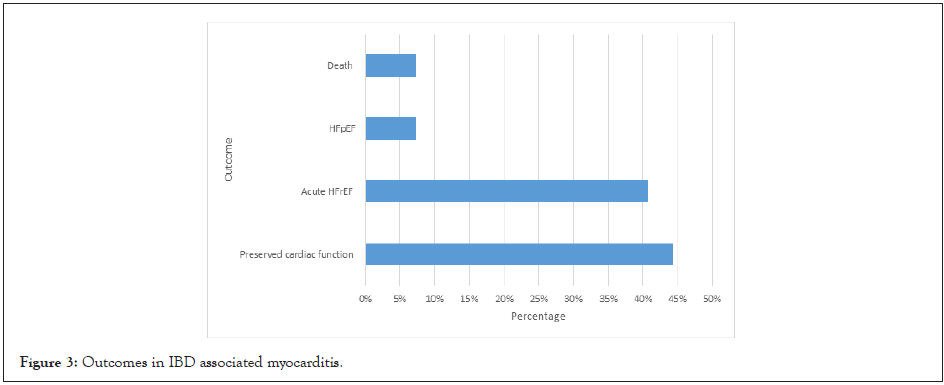

78% of IBD associated myocarditis was treated with steroids (Figure 1). Current European guidelines suggest consideration of immunosuppression in proven non-infectious autoimmune myocarditis. Using steroids alone or steroids and azathioprine has the most evidence [5]. 81% of patients treated with steroids required an adjunct immunosuppressive agent. 22% cases required a biologic agent, which was similar among CD and UC patients. 26% of cases developed acute Heart Failure with reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF) with associated cardiogenic shock requiring inotropic support; however, all patients made a complete recovery. Overall, acute heart failure occurred in 48% of patients and HFrEF (85%) was more common than HFpEF (15%). Complete recovery occurred in 77% of patients and there was partial recovery is 23% of patients. Cardiac function was preserved in 48% of patients and cardiac arrhythmias were uncommon (7%).

Figure 1: Age distribution of patients with IBD associated myocarditis.

Outcomes in IBD-associated myocarditis

A recent large multicentre study evaluating outcomes in myocarditis found 26.6% patients had complicated acute myocarditis, defined by left ventricular ejection fraction <50% at first echocardiogram, sustained ventricular arrhythmias or a low cardiac output syndrome (inotropic requirement) [6]. In comparison, 44.5% of patients with myocarditis as an IBD EIM had complicated acute myocarditis. We used a <40% cut-off for ejection fraction. This increases to 51.9% when including patients who developed HFpEF. Mortality rate was 7.4% in our study group compared to 2.3% in acute myocarditis of all aetiology [6]. The long-term relapse rate of myocarditis across 4.5 years is reported at approximately 10% [7]. In comparison, 28% of IBD related myocarditis relapsed within 2 years. Despite the small sample size, these findings suggest increased morbidity and mortality in IBD associated myocarditis (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Distribution of IBD associated myocarditis among Crohn’s disease and Ulcerative colitis.

Figure 3: Outcomes in IBD associated myocarditis.

Diagnostic dilemma

Diagnosis of rare EIMs of IBD like myocarditis is challenging and requires a systematic approach. IBD patients have an increased long-term risk of myocarditis, especially severe myocarditis [8]. A recent study found the prevalence of myocarditis in UC and CD was 23.22 and 11.55 per 100,000 hospitalisations respectively [4]. Underlying immune dysfunction and IBD drug-related adverse events likely contribute to this. The true incidence of myocarditis as EIMs in IBD is likely underreported in the literature due to reduced awareness and difficulty in establishing the association. Diagnosis requires exclusion of typical infectious causes and consideration of toxin/drug mediated myocarditis and immunological syndromes. 5-aminosalicyclic acids, commonly used in UC, may cause myocarditis that typically presents within 4 weeks of commencing therapy. The mechanism is unclear although leading hypotheses include direct cardiac toxicity, immunoglobulin E mediated allergic reaction, cell-mediated hypersensitivity or a humoral antibody response [9]. Myocarditis occurring with active IBD in the absence of infectious and medication-related causes is suggestive of an EIM. However, establishing myocarditis as an EIM in undiagnosed IBD remains challenging due to the absence of specific cardiac imaging findings or presentation features. In these patients, performing faecal calprotectin may be reasonable to guide prompt treatment and reduce complications.

cMRI improves diagnostic accuracy of myocarditis in hemodynamically stable patients. Diagnosis is established using the Lake Louise criteria from 2018. Our review demonstrated that 50% of patients who underwent cMRI had atypical findings, with subendocardial late gadolinium enhancement occurring most commonly. This highlights the importance of high clinical suspicion to establish the diagnosis.

Role of TNF-α inhibitors

The pathophysiology of EIMs in IBD remains unclear. Leading hypotheses including an extension of an antigen-specific immune response from the intestines to extraintestinal sites or an independent inflammatory event triggered by the presence of IBD [10]. This involves a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors, and the gut microbiota. Tumour Necrosing Factor (TNF) is thought to be integral in IBD and many EIMs, as supported by its successful treatment using TNF-α inhibitors. Myocarditis occurring as EIM in IBD is likely immunemediated, secondary to autoantigen exposure [11]. TNF-α has a dual role in myocarditis. Its well-established pro-inflammatory role involves mediating adhesion of inflammatory cells to cardiac microvascular endothelial cells in the early phase of inflammation [12]. The mechanism of its cardioprotective effects is less clear but proposed to involve TNF-α signalling mediated apoptosis of pathogenic heart reactive effector T cells and thus, immune response regulation [12]. Experimental models have suggested the possibility of an unrecognised factor that determines if TNF-α exerts pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory effect [12]. Similarly, TNF-α likely has a dual role in IBD. TNF is integral in mediating the late phase of inflammatory cascade and chronic intestinal mucosal inflammation via triggering secretion of proinflammatory mediators (including IL-1β), local expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells and recruitment and activation of lymphocytes and granulocytes [13]. During the early phase of inflammation, TNF may act to preserve the integrity of the intestinal barrier and thus, protect against the initiation of the inflammatory cascade [13]. However, this phase typically occurs in the pre-clinical setting.

Evidence in managing rare EIMs of IBD is limited. As demonstrated in our literature review, TNF-α inhibitors are the most commonly used adjunct biologic in myocarditis occurring as an EIM, in-keeping with its indication in other EIMs and multiple autoimmune conditions. However, the different disease phases highlight the challenge of appropriate timing for TNF-α inhibition. Many trials have demonstrated a lack of clinical improvement and some have shown worsening of cardiac function and mortality in chronic heart failure patients receiving infliximab [14]. However, the neurohormonal activation leading to cardiac remodelling occurs as a long-term consequence of reduced cardiac output, which is starkly different to acute myocarditis related heart failure. The effectiveness of infliximab demonstrated in our literature review suggests a window to target the reversible inflammation prior to onset of chronic cardiac remodelling. Importantly, worsening of cardiac function was not seen in any patients, supporting its safety in acute myocarditisrelated heart failure.

Emerging evidence of IL-1 blockade

There is emerging evidence on the role of IL-1, a family of proinflammatory cytokines, in the pathogenesis of myocarditis irrespective of aetiology. IL-1α is released on cell death and responsible for inducing inactive IL-1β precursor production by monocytes, macrophages and neutrophils. Interaction of IL- 1β precursor with the NKRP3 inflammasome, an intracellular macromolecular structure, results in its secretion and cleavage to its active constituent [15]. These cytokines mediate inflammation of cardiomyocytes, progressively resulting in further apoptosis and ultimately, impaired contractile function and arrhythmias [16]. IL-1 blockade with Anakinra has been used successfully to treat refractory myocarditis and associated inflammatory heart failure [17-19], with rapid improvements in systemic inflammation, cardiac function and arrhythmic burden. Experimental models also support its potential benefit [15]. The largest randomised controlled trial evaluating anakinra for treatment of acute myocarditis found no significant reduction in myocarditis complications (heart failure requiring hospitalisation, chest pain requiring medication, left ventricular ejection fraction <50%, and ventricular arrythmias) [20]. Both groups received guidelinedirected standard of care and there were no safety concerns. However, this trial enrolled all patients with myocarditis at diagnosis rather than select cases of refractory myocarditis. The study population was at low risk of complications. The high rate of relapse, progression to acute HFrEF and cardiogenic shock seen in our analysis suggests patients with IBD related myocarditis are a high-risk group. Further trials evaluating IL-1 blockade in groups at high-risk of complications are needed.

IL-1β is also an important mediator of inflammation in IBD through recruitment and activation of immune cells and inducing T helper 17 (Th17) differentiation, a key step in pathogenesis of IBD [21]. Studies have demonstrated numerous miRNAs modulate mucosal barrier function and downregulate IL-1β mediated inflammation to maintain mucosal homeostasis. IL-1β expression is raised in plasma and mucosa of IBD patients and positively correlate with severity of mucosal inflammation [22]. Clinical evidence exploring IL-1 blockade in IBD is limited. Some case reports describe successfully inducing UC clinical remission with Anakinra [23]. A retrospective study found Canakinumab (IL-1β monoclonal antibody) achieved statistically significant clinical response in children with very early onset IBD [24]. However, a phase II trial found that Anakinra provided no benefit compared to steroids alone in reducing the need for rescue therapy in acute severe UC [25]. Furthermore, worsening of IBD and possible Anakinra induced IBD has been reported, highlighting potential safety concerns [26,27]. These paradoxical findings reflect our limited understanding of IL-1β in IBD and highlight the need for further studies.

α4β7 integrin inhibition

Vedolizumab is a gut selective α4β7 integrin inhibitor used in IBD. Results from a recent multicentre retrospective study support its role in management of many EIMs, particularly in patients with active luminal disease, although the mechanism remains unclear [28]. In our review, vedolizumab, without adjunct TNF-α inhibition, was used to successfully treat two myocarditis cases with active UC. In appropriately selected patients, vedolizumab may be considered as a second-line agent (Table 1).

| Case | Age | Sex | IBD phenotype | IBD disease activity status | Time since IBD diagnosis (Years) | Atypical cardiac MRI findings | Treatment | Outcome | Relapse of myocarditis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McGrath-Cadell et al. [29] | 27 | Female | Crohn’s | Active | 0.42 | Mobile masses on mitral valve | Steroids | Preservation of cardiac function (hypokinetic basal inferolateral wall) | Yes |

| Belin et al. [30] | 56 | Female | Crohn’s | Active | - | Contrast enhancement from the subendocardium | Steroids and infliximab | Acute HFrEF with complete recovery | No |

| Gruenhagen et al. [31] | 24 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Active | 0 | No | Steroids and mesalamine | Preservation of cardiac function | No |

| Nash et al. [32] | 46 | Male | Crohn’s | Active | 19 | - | Steroids, cyclophosphamide, IVIG, azathioprine, etanercept | Acute HFrEF and death | N/A |

| Weiss et al. [33] | 44 | Male | Crohn’s | Inactive | Preceding diagnosis (1 month) | - | Steroids and olsalazine | Acute HFrEF with partial recovery | No |

| Nishtar et al. [34] | 21 | Female | Crohn’s | Active | 0 | - | Ventilatory and inotrope support, mesalazine | Acute HFrEF and cardiogenic shock with complete recovery | No |

| Oh et al. [35] | 19 | Female | Crohn’s | Active | 0 | - | Ventilatory and inotrope support, steroids and mesalazine | Acute HFrEF and cardiogenic shock with complete recovery | No |

| Kumar et al. [36] | 37 | Male | Crohn’s | Active | - | No | Steroids and colchicine | Preservation of cardiac function | No |

| Caio et al. [37] | 26 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Active | 1 | No | Steroids and vedolizumab | Preservation of cardiac function (hypokinesis apical anterior aspect of myocardium-resolved) | Yes |

| Shibu et al. [38] | 45 | Female | Crohn’s | Active | 25 | Subendocardial late gadolinium | Steroids, infliximab and anakinra | HFpEF with partial recovery | Yes |

| enhancement, transmural infarction | |||||||||

| Mowat et al. [39] | 15 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Active | 0 | - | Steroids and sulfasalazine | Preservation of cardiac function | Yes |

| Frid et al. [40] | 19 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Inactive | 7 | - | Steroids, lidocaine, anti-arrhythmics | Preservation of cardiac function | No |

| Frid et al. [40] | 11 | Male | Crohn’s | Inactive | Preceding diagnosis (3.5 years) | - | Steroids | Preservation of cardiac function | No |

| Ryzko et al. [41] | 11 | Female | Crohn’s | Active | 0 | - | Steroids, EEN, azathioprine and mesalamine | Preservation of cardiac function | No |

| Wang et al. [42] | 15 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Active | 2 | No | Steroids and mesalamine | Preservation of cardiac function | No |

| Kim et al. [43] | 13 | Male | Crohn’s | Active | 0 | - | Steroids, EEN, inotrope support | Acute HFpEF and cardiogenic shock with complete recovery | No |

| Alyacoub et al. [44] | 25 | Female | Ulcerative colitis | Active | - | - | Steroids, vedolizumab, inotropic support | Acute HFrEF and cardiogenic shock with complete recovery | No |

| Piazza et al. [45] | 22 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Active | 0 | No | Steroids and mesalazine | Preservation of cardiac function (inferior and septal hypokinesia) | No |

| Kim et al. [46] | 28 | Female | Ulcerative colitis | Active | - | - | Steroids, infliximab and ECMO | Acute HFrEF with complete recovery | No |

| Varnavas et al. [47] | 30 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Active | 1 | Absence of late gadolinium enhancement | Steroids, azathioprine, mesalamine, inotropic support, | Acute HFrEF and cardiogenic shock with complete recovery | Yes |

| intra-aortic balloon pump | |||||||||

| Mohite et al. [48] | 31 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Active | 14 | - | Inotrope support, ECMO, intra-aortic balloon pump | Acute HFrEF and cardiogenic shock with complete recovery | No |

| Hyttinen et al. [49] | 37 | Female | Crohn’s | Inactive | 4 | - | Immunosuppressive therapy (unspecified) | Preservation of cardiac function, Complete heart block requiring pacemaker | Yes |

| Sikkens et al. [50] | 46 | Male | Crohn’s | Active | 0 | - | CPR | Ventricular fibrillation, cardiac arrest and death | N/A |

| Williamson et al. [51] | 18 | Male | Crohn’s | Active | 0 | - | Subtotal colectomy and ventilatory and inotropic support | Acute HFrEF and cardiogenic shock with complete recovery | No |

| Freeman et al. [52] | 26 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Active | 6 | - | Steroids | Atrial flutter, preservation of cardiac function | Yes |

| Murphy et al. [53] | 42 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Active | 0 | Delayed widespread subendocardial enhancement | Steroids and ICD | Acute HFrEF with partial recovery | No |

| Chennupati et al. [54] | 21 | Male | Crohn’s | Inactive | 2 | - | Ibuprofen and colchicine | Preservation of cardiac function | No |

Note: Acronyms:- EEN: Exclusive Enteral Nutrition; IVIG: Intravenous Immunoglobulin; ECMO: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation; CPR: Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation; HFpEF: Heart Failure with preserved Ejection Fraction; FrEF: Heart Failure with reduced Ejection Fraction; HFrEF was defined by an ejection fraction <40% with a clinical syndrome of heart failure; HFpEF was defined by an ejection fraction of >50% with a clinical syndrome of heart failure; Complete recovery was defined as normalisation of ejection fraction and resolution of heart failure symptoms; Partial recovery was defined as improvement in ejection fraction or heart failure symptoms; Preservation of cardiac function was defined as absence of clinical heart failure syndrome and normal ejection fraction. Some of these patients had focal myocardial hypokinesis without a clinical heart failure syndrome.

Table 1: Summary of reported cases of myocarditis occurring as an extraintestinal manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease.

Myocarditis is a rare EIM of IBD that is associated with worse outcomes compared to the general acute myocarditis population. Both CD and UC patients are affected, and diagnostic evaluation should involve a systematic approach including cMRI in stable patients, with attention to atypical findings. Aggressive immunosuppression with steroids should be first-line therapy. Our review suggests infliximab and vedolizumab should be considered in steroid refractory IBD-related myocarditis, including those with acute inflammatory heart failure. Although IL-1 appears to be critical in pathogenesis of IBD and myocarditis, there is limited clinical evidence for IL-1 blockade in either population group. It remains an attractive therapeutic target; however, further studies are required to clearly define its pathogenic role and address potential safety concerns of IL-1 inhibitors in IBD patients.

All authors critically revised the manuscript, approved the final version for submission and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref]

Citation: Shibu R, Mohsen W (2024). Myocarditis as an Extraintestinal Manifestation of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Clin Exp Cardiolog. 15:899.

Received: 06-Aug-2024, Manuscript No. JCEC-24-33374; Editor assigned: 08-Aug-2024, Pre QC No. JCEC-24-33374 (PQ); Reviewed: 22-Aug-2024, QC No. JCEC-24-33374; Revised: 29-Aug-2024, Manuscript No. JCEC-24-33374 (R); Published: 05-Sep-2024 , DOI: 10.35248/2155-9880.24.15.899

Copyright: © 2024 Shibu R, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.