Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-9600

ISSN: 2155-9600

Research Article - (2022)Volume 12, Issue 1

Objective: To assess nutritional and health practice and associated factors among pregnant women based on the Essential Nutrition Action (ENA) framework.

Methods: A community based cross-sectional study design with quantitative data collection method was employed from June 1, 2018 to April 1, 2018 in Ambo district. A multi-stage sampling technique was used among 750 pregnant women aged 18-49 years. A semi structured questionnaire was used to collect data. Descriptive statistics, bivariate and lastly multivariate binary logistic regressions analysis was used to control confounders. P value <0.05 was used to declare statistical significance.

Results: The overall optimal nutrition and health practice of pregnant women in the study area was 205 (27.3%). Respondent occupation being farmer with (AOR=0.258, 95% CI:0.070, 0.955), husband occupation being merchant with (AOR=2.964, 95% CI:1.074, 8.181), husband educational status (being grade 5-8 with (AOR=2.097, 95% CI:1.045, 4.207), being grade 9-12 with (AOR=4.646, 95% CI:2.243, 9.621), having diploma and higher education with (AOR =6.825, 95%CI: 2.254, 20.669), gravida (AOR=0.461, 95% CI:0.126, 0.980), Antenatal care visit (AOR=35.134, 95%CI: 16.150, 76.430) and having health and nutrition information (AOR=2.328, 95%CI: 1.394, 3.888) were significantly associated with nutritional and health practice.

Conclusions: According to current study, the overall optimal nutrition and health practice of pregnant women in the study area was low. Respondent occupation, husband occupation, husband educational status, gravida, Antenatal care visit and having health and nutrition information were significantly associated with nutritional and health practice.

Nutritional and health practices; Pregnant women; Ambo

Nutrition is considered to be the bedrock of wellbeing and prevention of ill health in the society. It is also an essential factor in promoting health of the pregnant women as well as the community [1]. Health and nutrition are closely linked; a person must be well nourished to be healthy, while poor health can affect nutritional status [2].

Women's optimal nutritional intake is critical for their own health and increased work capability, as well as the health of their children [3]. Pregnant women require a wide variety of foods, as well as at least one more meal each day than non-pregnant women and lots of safe water. Iron-rich foods and iodized salt, as well as a reduction in high workloads, are essential for mother and fetus growth [4-6].

The following are examples of optimal nutrition and health practices for pregnant women based on the ENA framework and various findings: Pregnant women should eat more frequently and in larger quantities, consume a variety of meals from both plant and animal origin and use iodized salt for the whole family, supplemented with micronutrients (iron/folate), follow disease preventive and treatment measures (top priority for malaria and deworming), and be encouraged to have supportive lifestyle and care (reduced Work load and self-decision making status) [7-9].

Malaria and deworming prevention and treatment, as well as cleanliness as a component of optimal nutrition and health practices, are given top importance in disease prevention and treatment practices [10-15].

Work load and status of pregnant women in the household are the immediate causes that affect (directly/and or indirectly) optimal nutrition practices of pregnant women under supportive lifestyle and care. Energy-deficient women can preserve energy by minimizing heavy work, limiting work hours, and getting appropriate rest. Women in some cultures are less able to access resources and make decisions about how to use them to enhance their health and nutrition, especially during pregnancy, due to their social standing [16,17].

At the request of USAID/Ethiopia, from March 2003 to September 2006, LINKAGES provided support to the Ethiopian government and its partners for the introduction of the ENA package as a golden approach to improve the nutritional and health status of women and children less than two years of age. Accordingly, the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) adopted this approach and included in child survival strategies in 2004 [18].

According to the World Health Organization, pregnant women should take iron tablets during their pregnancy or for six months, and if they are anemic, they should continue taking iron and folic acid each day for three months following birth [19,20]. According to the 2016 EDHS (Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey), 22% of Ethiopian women are too thin (BMI 18.5 Kg/m2), and 24% are anemic [21]. According to a survey conducted in the Gedeo zone of southern Ethiopia in 2018, around one-third (32.2%) of pregnant women had good dietary practices in 2018 [22].

According to various researchers, socio demographic factors such as age, wealth index, residence, size of farmland, and illiteracy or low education are common factors affecting maternal nutrition and health status; similarly, maternal and health service related factors such as years at marriage, ANC visits, level of nutritional knowledge and food practices (consume additional food during pregnancy and variety of food from both animal and plant origins; and maternal and health service related factors such as years at marriage, ANC visits are common factors affecting maternal nutrition and health status [23-26].

To the best of our knowledge, no study based on the ENA framework has been conducted on the overall prevalence of optimal nutrition and health practices of pregnant women and their associated factors.

As a result, the goal of this study was to establish the prevalence of nutritional and health practice, as well as associated factors, among pregnant women in the study area, using the essential nutrition action framework.

A community based cross-sectional study design was conducted from June 1, 2018 to April 1, 2018 among pregnant women in Ambo district of West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia. Ambo district is located in western part of Ethiopia 114 km from Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. Based on 2015 district health office, it has 37,454 and 6976 reproductive age group and pregnant women respectively [27].

Source population and study populationAll pregnant women in the district were the source population, whereas randomly selected pregnant women in the selected kebele’s (the smallest administrative units) were the study population.

Inclusion criteria: Pregnant women aged 18-49 years and who lived in the study kebele’s at least for 6 months were included in this study.

Exclusion criteria: Pregnant women who were severely sick and or not able to respond the questions were excluded.

Pregnant women who had confirmed or diagnosed chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, Tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS and those enrolled in intervention programs such as supplementary feeding or general food distribution as these intervention would have an impact on nutritional and health practice and thus bias the results of the study.

Sample size determination and sampling techniqueThe sample size was calculated using single population proportion with the assumption that 34% (26) of pregnant mothers had optimal nutrition practices during pregnancy with 5% marginal error and 95% confidence level, a design effect of 2 and 10% none response rate. Accordingly the final sample size obtained was 770 pregnant women.

A multi-stage sampling technique was used to select 770 study participants. The total Kebele's in the district were stratified into rural and urban areas. Simple Random Sampling (SRS) with the lottery method was used to select twelve Kebeles (2 urban and 10 rural) from the existing 39 kebeles (6 urban and 33 rural). Based on proportional to the size allocation, eligible households were selected using simple random sampling with computer generated random number among selected kebeles. A family folder prepared by kebele’s Health Extension Workers (HEWs) was used as sampling frame of household. The women’s pregnancy status was assessed by inquiring about her last menstrual period and confirming with a pregnancy test.

Data collection tools and proceduresA semi structured questionnaire prepared in English language was used to collect data. The questionnaire was translated into two languages (Afan Oromo and Amharic) then back to English by language experts to keep its consistency. The questionnaire was pretested in Ginchi town which is nearby to Ambo district on 39 (5%) of the total sample size to identify any ambiguity, length, completeness, consistency and acceptability of questionnaire and some skip patterns were corrected before the real data collection.

Eight diploma nurses were recruited to collect data. Additionally, three female laboratory technicians were recruited to do pregnancy tests. Training was given to the data collectors on the objective and relevance of the study, confidentiality of information, respondent’s right, informed consent and techniques of interview. Data collectors administered the questionnaire through a face-to-face interview at the participants' homes. To maintain the optimal privacy of the mothers, other family members didn’t have free access to the place where the interviews were conducted. The filled questionnaires were checked for consistencies and completeness daily by four supervisors who had BSc degree in Nursing and principal investigators on the spot. Part one of the questionnaire consists of socio-demographic and economic factors, Part two of the questionnaire consists of maternal characteristics, and Part three of the questionnaire consists of knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards nutrition and health of pregnant women. Questions about knowledge, attitudes, and practices were derived from a guide of formative research for Promoting Maternal Nutrition and an essential nutrition action frame work.

Knowledge of pregnant women about nutrition and health was assessed by using 14 questions that were used to assess knowledge of pregnant women regarding nutrition and health was adapted based on the recommendation of ENA message. A knowledge score was calculated for each participant based on the number of questions that were correctly answered in the knowledge assessing questions section. Each correct response was scored 1 and incorrect response scored 0. The scores were summed and ranked into terciles (three parts). Pregnant woman was considered to have poor knowledge about nutrition and health if she scored below the highest tertile (i.e. in the first and/or second tertile) and good knowledge about nutrition and health if she scored in the third tertile.

Attitude towards nutrition and health was assessed by asking eleven attitude questions. When the pregnant women agreed for questions regarding attitude, she has a score of 2 points, for neutral a score of 1 point and if she respond disagree, scored 0 point following the Likert scale. Then, the total attitude score was determined for each pregnant woman by summing up the scores across the eleven attitudes related questions. Pregnant woman was considered to have unfavorable attitudes if she scored below the third tertile and favorable attitude if she scored in the third tertile.

The ENA framework was used to assess the outcome variable (i.e. nutrition and health practice), which included questions regarding dietary quantity, dietary quality, micronutrient intake, diseases prevention and treatment practice, and supportive life style and care. The respondents were asked to select Yes=1 or No=0 responses to indicate whether or not a set of five primary subthemes was practiced. Scores for the practice factors were generated to determine the respondents' practice. For each respondent's replies to all 20 nutrition and health practice related questions, one point was assigned for a correct response and zero for an erroneous response, and the sum of the total scores for the practice ranged from (0 to 20 points maximum score) for each respondent's answers for all 20 nutrition and health practice related questions and this score was converted to tertile (three parts). If a pregnant woman scored below the third tertile, she was judged to have suboptimal nutrition and health practices, but if she scored in the third tertile, she was considered to have optimal nutrition and health practices (28).

Operational definitionsDuring her pregnancy, a pregnant mother's nutritional and health practices include the following basic action message (five subthemes) according to ENA framework.

Dietary quantity

Dietary quality

Micronutrient supplements

Supportive lifestyle and care

Optimal nutrition and health practice: when women had a good quantity of diet, good quality of diet, took daily iron and folic acid supplements for at least three months, and good disease prevention and treatment practice, as well as a good supportive lifestyle and care, whereas suboptimal nutrition and health practice: when women had a poor quantity of diet, poor quality of diet, or took daily iron and folic acid supplements for less than three months or poor disease prevention and treatment practice, and poor supportive lifestyle and care [28].

Women's nutrition and health knowledge: A pregnant woman was regarded to have good nutrition and health knowledge if she scored in the highest (third) tertile on knowledge-related questions, or poor nutrition and health knowledge if she scored below the highest tertile[28].

Attitude toward nutrition and health: The reactions of pregnant women's positioning, goals, thinking, or behavior concerning nutrition and health-related concerns throughout pregnancy. If a pregnant woman scored in the third tertile on attitude-related questions, she was judged to have a favorable attitude; if she scored below the third tertile, she was regarded to have an unfavorable attitude [29].

Data processing and analysisData were checked manually for completeness and consistency during data collection before data entry. Then it was entered in to Epi Info version 7.2.2 software and exported to SPSS for windows version 21 for cleaning and analyses.

First, descriptive statistics like mean and Standard Deviation was done for continuous variable and frequency and percentage for categorical data.

Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to assess predictors. The Hosmer -Lemeshow goodness of fit statistic is used to assess model goodness of fit. Correlation between independent variables was checked using the Pearson Correlation Coefficient. Multicollinearity was checked using Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) and there was no Multicollinearity between independent variables. Bivariate analysis was performed between nutrition and health practice during pregnancy and associated factors one at a time. Their odds ratios (OR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) and p-values was obtained. Factors that were significantly associated with nutrition and health practice of mothers during pregnancy at p-value <0.25 in bivariable analysis were entered to multivariate binary logistic regression. Backward elimination was used, and p-Values at <0.05 was used to declare statistical significance.

Data quality controlThe questionnaire was adapted from standard data collection instruments, and it was pretested. Cronbatch’s alpha value of knowledge and practice >0.7 for the whole scale of the instrument was obtained which make it fit for use in the study area. Training of data collectors, supervisors, and laboratory technicians was undertaken for three days. The questionnaire was also translated in to language spoken the study area (Afan Oromo and Amharic) to facilitate understanding of the respondents. Supervisors and principal investigator were closely followed the data collection process. Filled questionnaires were checked daily for completeness and any other missing and errors were corrected. Important assumptions were checked using the standard procedures.

A total of 750 pregnant women were interviewed, with a 97.4% response rate. The study comprised 608 pregnant women from rural kebeles (81.1%) and 142 pregnant women from urban kebeles (18.9%). Pregnant women's ages ranged from 18 to 38, with the mean (standard deviation) of the respondents' ages being 27(4.4). In terms of educational attainment, 286 (38.1%) of pregnant women and 219 (29.5%) of their husbands had no formal education. In terms of occupation, 607 pregnant women (80.9%) were housewives, while 457 (60.9%) of their husbands were farmers. About a quarter of pregnant women, 180 (24 percent), had more than five family members, with a mean family size of 4.5(1.6) people (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of the pregnant women in Ambo district, Ethiopia, 2016, (n=750).

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | Rural | 608 | 81.1 |

| Urban | 142 | 18.9 | |

| Religion of the respondents | Orthodox | 346 | 46.1 |

| Protestant | 319 | 42.5 | |

| Wakefeta | 40 | 5.3 | |

| Others | 45 | 6 | |

| Ethnicity | Oromo | 672 | 89.6 |

| Amhara | 58 | 7.7 | |

| others | 20 | 2.7 | |

| Occupation of respondents | Employed | 40 | 5.3 |

| Housewife/ Daily laborers | 618 | 82.4 | |

| Merchant | 42 | 5.6 | |

| Farmers | 50 | 6.7 | |

| Husband occupation | Employed | 82 | 10.9 |

| Merchant | 82 | 10.9 | |

| farmer | 457 | 60.9 | |

| Daily laborer | 71 | 9.5 | |

| Private workers | 58 | 7.7 | |

| Respondent educational status | No formal education | 286 | 38.1 |

| 1-4 Grade | 179 | 23.9 | |

| 5-8 Grade | 184 | 24.5 | |

| 9-12 Grade | 74 | 9.9 | |

| Diploma and Higher | 27 | 3.6 | |

| Husband educational status | No education | 219 | 29.2 |

| 1-4 Grade | 140 | 18.7 | |

| 5-8 Grade | 189 | 25.2 | |

| 9-12 Grade | 146 | 19.5 | |

| Diploma and higher | 56 | 7.5 | |

| Head of your household | Husband | 703 | 93.7 |

| Myself | 41 | 5.5 | |

| Other*** | 6 | 0.8 | |

| Household size | 01-Mar | 213 | 28.4 |

| 04-May | 357 | 47.6 | |

| Greater than 5 | 180 | 24 | |

| Household wealth tertile | Poor | 219 | 29.2 |

| Medium | 329 | 43.9 | |

| Rich | 202 | 26.9 |

*Catholic, **Tigre, Gurage, and silte ***Grandmother, Grandfather

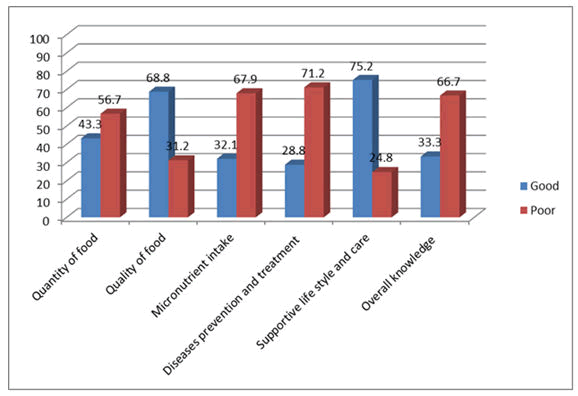

Knowledge of pregnant women on nutrition and health practice: About 325 (43.3%) of the respondents were well-informed about the significance of eating more frequently and in larger amounts during pregnancy (quantity). Five hundred sixteen (68.8%) had good understanding of the quality (variety) of diet to be consumed during pregnancy. Similarly, 241 (32.1%) of the survey participants were well-versed in micronutrient-related topics. Around 30% of participants had a good understanding of disease prevention and treatment questions, while three-quarters (75.2%) of individuals had a good understanding of supportive life style and care questions. In this study, 250 study participants (33.3%) had good knowledge of overall nutrition and health issues (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Knowledge of pregnant women on nutrition and health related issues in Ambo district, 2016.

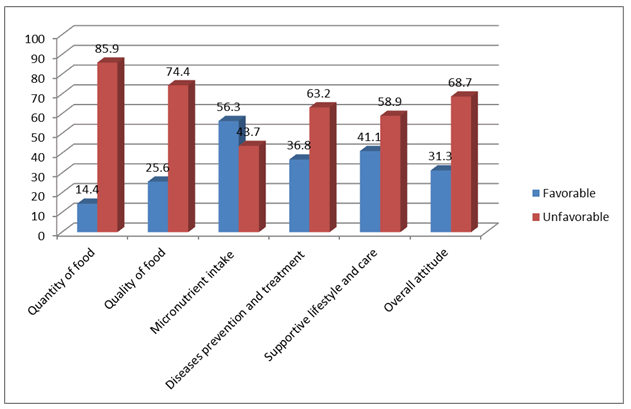

Attitude of pregnant women towards nutrition and health practice: About 108 (14.4%), 192 (25.6%), 422 (56.3%), 276 (36.7%), and 308 (41.1%) pregnant women expressed a positive attitude toward each subtheme of nutrition and health-related questions throughout pregnancy, respectively. In this study, 235 (31.3%) of respondents expressed a favorable attitude of nutrition and health practices (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Attitude of pregnant women on nutrition and health related issues in Ambo district, 2016.

Nutrition and health related practices of the study participants: Only 30 (7.0 percent) of the 426 participants who took iron/folate supplements during pregnancy supplemented for a total of three months or more. Majority, 609 (81.2%) of pregnant women used non iodized salt for cooking/preparing their food, Even among those who used iodized salt, 53 (37.6%) of pregnant women improperly stored and/or placed it.

About two-thirds of pregnant women, 462 (61.6%), had a history of illness during pregnancy, and 275 (59.5%) of those women did not seek care from health institutions. In terms of counseling, 445 pregnant women (59.3%) received diet and health-related advice. During pregnancy, 437 (58.3%) of pregnant women ate additional foods than usual, and 426 (56.8%) ate a variety of foods.

During pregnancy, 694(92.5%) of women shared food with their family members. The majority of pregnant women, 661 (88.1%), 544 (72.5%), and 522 (69.6%), got support from family or community, had enough rest, and passed self-decisions in the household linked to nutrition and health issues during pregnancy, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2: Nutrition and health related practices of pregnant women in Ambo District, Ethiopia, 2016, (n=750).

| Variables | Category | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supplemented iron/folate during pregnancy | No | 324 | 43.2 |

| Yes | 426 | 56.8 | |

| Duration of supplementation | <3 months | 720 | 93 |

| >3 months | 30 | 7 | |

| Reason for not supplementation | No access for iron/folate tablet | 121 | 37.3 |

| Its cost | 13 | 4 | |

| It has gastric irritation | 87 | 26.9 | |

| Didn't go to health institution | 103 | 31.8 | |

| kind of salt used | Iodized | 141 | 18.8 |

| Not iodized | 609 | 81.2 | |

| Method of storage (If Iodized) | Covered and in appropriate place | 88 | 62.4 |

| Anywhere in the kitchen | 45 | 31.9 | |

| Wet and not covered | 8 | 5.6 | |

| If used non iodized salt, reason | Not available | 291 | 47.8 |

| It's cost | 115 | 18.8 | |

| Lack of information | 203 | 33.4 | |

| History of illness during pregnancy | No | 288 | 38.4 |

| Yes | 462 | 61.6 | |

| Seek treatment from HI | No | 275 | 59.5 |

| Yes | 187 | 40.5 | |

| Counseled on nutrition and health related issues during pregnancy | No | 305 | 40.7 |

| Yes | 445 | 59.3 | |

| If no, reason | I have not attend health institution | 132 | 30.7 |

| Health professionals didn't attend my house | 148 | 34.4 | |

| Unwillingness of health professionals | 95 | 22.1 | |

| Health professionals are busy | 55 | 12.8 | |

| Ate additional foods during pregnancy | No | 437 | 58.3 |

| Yes | 313 | 41.7 | |

| If No, reason | No need to increase | 144 | 33 |

| Fetus increase in size and result in difficulty during labor | 134 | 30.7 | |

| My economic status is not allowed | 120 | 27.5 | |

| Ate variety of food | Yes | 426 | 56.8 |

| No | 324 | 43.2 | |

| Sharing of food | Yes | 694 | 92.5 |

| No | 56 | 7.5 | |

| Support from the family/Community | Yes | 661 | 88.1 |

| No | 89 | 11.9 | |

| Had enough rest | Yes | 544 | 72.5 |

| No | 206 | 27.5 | |

| Self-decision in the household | Yes | 522 | 69.6 |

| No | 228 | 30.4 |

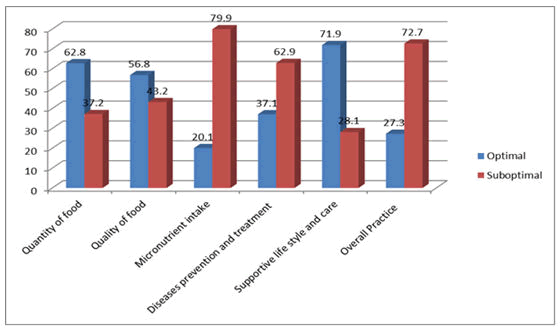

Optimal nutrition and health related practices of the study participants: Four hundred seventy one, (62.8%) of them had good practice in terms of quantity of diet, 426 (56.8%) of them had good practices in terms of food quality (variety), 151 (20.1%) of them had supplemented Iron/folate for three months or more, 278 (37.1%) of pregnant women had good practices in disease prevention and treatment measure, and 539 (71.9%) of them had good practice in supportive life style and care during their pregnancy. According to the findings of the current study, about 205 (27.3%) of the study participants exhibited overall optimal nutrition and health practice (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Subtheme of nutrition and health related practices of pregnant women in Ambo district, 2016.

Factors associated with nutritional and health practices during pregnancy in Ambo district: Residence, age of the respondent, occupation of the respondents, occupation of the husband, husband educational status, wealth index, gap duration between pregnancy, number of pregnancy, Antenatal care visit, gestational age, having health and nutrition information, estimated time to reach health institution, knowledge about nutrition and health and attitude towards nutrition and health were found significant at p-value <=0.25 in bi-variate analysis. However, respondent occupation, husband Occupation, husband educational status, gravida, Antenatal care visit and having health and nutrition information were found significantly associated with optimal nutrition and health practices in multivariable binary logistic regression analysis (Table 3).

Respondent occupation was found to be significantly associated with optimal nutrition and health practices. The study showed that odds of optimal nutrition and health practices among farmers’ pregnant women was 74.2% less likely as compared to employed pregnant women (AOR=0.258, 95%CI: 0.070, 0.955). Pregnant women who had Merchants husbands were 3 times higher odds of optimal nutrition and health practices compared to pregnant women who had employed husbands (AOR=2.964,95%CI:1.074,8.181). Husband Education is significantly associated with optimal nutrition and health practices. Those pregnant women whose husbands attended 5-8 Grade, 9-12 Grade and who had Diploma and higher education were 2.097, 4.646 and 6.825 times more likely odds of optimal nutrition and health practices compared with no formal education (AOR=2.097, 95%CI: 1.045, 4.207, AOR=4.646, 95%CI: 2.243, 9.621 and AOR =6.825, 95%CI: 2.254, 20.669) respectively.

Pregnant women who had five and more pregnancy were 53.9% less odds of nutrition and health practice compared to pregnant women who had one pregnancy (AOR=0.461, 95%CI: 0.126, 0.980). Antenatal care visit was found to be significantly associated with nutrition and health practices. The study revealed that those pregnant women who visited health institution for Antenatal care were 35.134 times higher odds of optimal nutrition and health practices than pregnant women who had no Antenatal care visit (AOR=35.134, 95%CI:16.150,76.430 ). Similarly pregnant women who obtained health and nutrition information were 2.328 times more likely to practice optimal nutrition and health than their counter parts (AOR=2.328, 95%CI: 1.394, 3.888) (Table 3).

Table 3: Bivariate and multivariate binary logistic regression analysis for factors associated with nutrition and health practice among pregnant women in Ambo district, Ethiopia, 2016, (n=750).

| Variable | Category | Nutrition and health practice | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95%CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal | Suboptimal | |||||

| Residence | Rural | 150 | 458 | 1 | 1 | |

| Urban | 55 | 87 | 1.930(1.314,2.836) | 1.062(0.558,2.021) | 0.856 | |

| Age of the respondent | 18-24 Years | 64 | 116 | 1 | 1 | |

| 25-34 Years | 133 | 381 | 0.633(0.440,0.910) | 1.037(0.623,1.726) | 0.89 | |

| >35 Years | 8 | 48 | 0.302(0.135,0.678) | 0. 659(0.221,1.971) | 0.456 | |

| Respondents’ occupation | Employed | 19 | 21 | 1 | 1 | |

| House wives/Daily laborers | 161 | 457 | 0.389 (0.204,0.743) | 0.412(0.150,1.135) | 0.086 | |

| Merchants | 12 | 30 | 0.442(0.177,1.101) | 0.483(0.130,1.800) | 0.278 | |

| Farmers | 13 | 37 | 0.388(0.160,0.942) | 0.258(0.070,0.955) | 0.043* | |

| Husband occupation | Employed | 32 | 50 | 1 | 1 | |

| Merchants | 30 | 52 | 0.901(0.479,1.695) | 2.964(1.074,8.181) | 0.036* | |

| Farmers | 110 | 347 | 0.495(0.303,0.811) | 2.645(0.972,7.202) | 0.057 | |

| Daily laborers | 19 | 52 | 0.571(0.287,1.136) | 1.498(0.507,4.426) | 0.465 | |

| Private workers | 14 | 44 | 0.497(0.235,1.050) | 1.445(0.464,4.503) | 0.526 | |

| Husband educational status | No formal education | 33 | 186 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1-4 Grade | 34 | 106 | 1.857(1.055,3.269) | 1.291(0.649,2.568) | 0.467 | |

| 5-8 Grade | 45 | 144 | 1.859(1.033,3.346) | 2.097(1.045,4.207) | 0.037* | |

| 9-12 Grade | 66 | 80 | 4.941(2.560,9.537) | 4.646(2.243,9.621) | 0.000** | |

| Diploma and higher | 27 | 29 | 4.143(1.671,10.272) | 6.825(2.254,20.669) | 0.001** | |

| Household wealth tertile | Low | 67 | 152 | 1 | 1 | |

| Medium | 78 | 251 | 0.705(0.480,1.035) | 0.843(0.483,1.470) | 0.547 | |

| High | 60 | 142 | 0.959(0.632,1.454) | 0.575(0.297,1.113) | 0.1 | |

| Gravida | One Pregnancy | 44 | 75 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2-4 pregnancy | 116 | 348 | 0.568(0.371,0.871) | 1.413(0.765,2.609) | 0.269 | |

| 5 and Above Pregnancy | 45 | 122 | 0.629(0.379,1.042) | 0.461(0.126,0.980) | 0.024* | |

| Gap duration between last pregnancy | <3 years | 164 | 461 | 1 | 1 | |

| 3-5 years | 38 | 67 | 1.594(1.031,2.466) | 1.122(0.624,2.015) | 0. 701 | |

| Above 5 years | 3 | 17 | 0.496(0.144,1.715) | 0.254(0.058,1.116) | 0.07 | |

| Antenatal care visit | No | 8 | 306 | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 197 | 239 | 31.528(15.242,65.218) | 35.134(16.150,76.430) | 0.000** | |

| Gestational age | 1st trimester | 8 | 37 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2nd trimester | 87 | 249 | 0.633(0.440,0.910) | 0.439(0.147,1.309) | 0.14 | |

| 3rd trimester | 110 | 259 | 0.302(0.135,0.678) | 0.645(0.222,1.879) | 0.422 | |

| Health and nutrition information | No | 35 | 186 | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 170 | 359 | 2.517(1.679,3.772) | 2.328(1.394,3.888) | 0.001** | |

| Estimated time to reach health institution | <30 minutes | 56 | 100 | 2.132(1.386,3.278) | 1.342(0.764,2.357) | 0. .305 |

| 30-60 min | 87 | 209 | 1.585(1.089,2.306) | 1.441(0.888,2.339) | 0. .139 | |

| >60 min | 62 | 236 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Knowledge on nutrition and health | Poor Knowledge | 115 | 385 | 1 | 1 | |

| Good Knowledge | 90 | 160 | 1.883(1.351,2.624) | 1.265(0.787,2.032) | 0. .331 | |

| Attitude towards nutrition and health | Unfavorable Attitude | 127 | 388 | 1 | 1 | |

| Favorable Attitude | 78 | 157 | 1.518(1.083,2.127) | 0.619(0.382,1.004) | 0.052 | |

Significant association **p<0.01,*p-value<0.05

The goal of this study was to investigate the prevalence of nutritional and health practices, as well as associated factors, among pregnant women in Ambo District, West Shewa Zone, Ethiopia, using the Essential Nutrition Action frameworks.

Optimal nutrition and health during pregnancy has long been recognized as a requirement for a healthy pregnancy and birth, and women's nutritional and health habits play a key role[30]. The optimal nutrition and health practices of pregnant women in the study area were 27.3% (95% CI:24.2, 30.7). This was in line with a study conducted in Misha Woreda, South Ethiopia, and marginally in line with a study conducted in Guto Gida Woreda, East Wollega Zone, Ethiopia, where 29.5 percent and 33.9 percent of respondents, respectively, were found to have good dietary and nutritional practice respectively [31,32], and significantly lower than a research conducted in Malawi, which found that (57%) of pregnant women had adequate nutrition and food group practices during pregnancy [33]. The possible difference could be due to differences in socio-demographic characteristics, study area, sample size, and the fact that this study followed the Essential nutrition action frameworks, which included many variables that were difficult to compare with previous studies. To the researcher knowledge no study was done in the overall status of nutritional and health practice following ENA frameworks.

The occupation of respondents was found to be significantly associated with optimal nutrition and health practice. According to the study, pregnant women who work as farmers have less odds of optimal nutrition and health practice as compared to those employed pregnant women. This could be due to the fact that 608 pregnant women (81.1%) came from a rural community, and the majority of rural Ethiopians practiced labor-intensive farming and lived hand to mouth [34]. Another reason could be that farmers' pregnant women spend a lot of time in the field (farming area) and expend a lot of energy, don't get enough rest, and don't have time to prepare food or seek medical help. Energy-deficient women can save energy for foetal development and growth by minimizing heavy work and reducing working hours. To produce breast milk and fetal nutrition, nutrients are mobilized from maternal stores, and a pregnant woman's nutrient stores are vulnerable to depletion if she is not assigned with less work or does not get enough rest during pregnancy [35].

Compared to pregnant women with working husbands(employed), pregnant women with merchant husbands had higher odds of optimal nutrition and health practices. Even if the evidence does not support this conclusion, one possible explanation is that merchant husbands may save money from their profits and thus become self-sufficient, assisting his wife and family in meeting the necessary nutritional and health-related requirements during pregnancy.

In our study site, husband education is significantly associated with optimal nutrition and health practice. As the husbands' education level improved, the likelihood of optimal nutrition and health practice increased. This finding was consistent with a study of dietary patterns and their determinants among pregnant women in the Gedeo zone of southern Ethiopia, which found that respondents with formal education had a higher odds of good dietary practices than those without formal education [22]. Similarly, a research conducted in Harar, Ethiopia, found that the risk of malnutrition was doubled among women who had illiterate husbands compared to those who had literate husbands [36]. The explanation for this could be that knowledge is vital in eliminating undesired behaviors and leading them to optimal practices that lead to a healthy life, and this encourages husbands to assist their wives in practicing healthier habits. Another explanation is that a husband with a higher level of education has more opportunities to obtain nutrition and other health-related information from a variety of sources, including online resources, leaflets, magazines, books, and other media, and to assist his pregnant wife in meeting her nutritional and health-related needs during pregnancy.

When compared to pregnant women who had one pregnancy, pregnant women who had five or more had 53.9% less odds of optimal nutrition and health practice. The reason for this could be that, if a household has a large number of children, food sharing of pregnant women by other family members, including children is more likely. According to this study, around 93 percent of pregnant women experienced food sharing, which could lead to suboptimal nutrition and health practice for pregnant women [37].

Antenatal care visits were found to be significantly associated with optimal nutrition and health practice, according to the study. This finding is consistent with a study on dietary practices and their determinants among pregnant women conducted in Gedeo Zone, southern Ethiopia, which found that pregnant women who received ANC were significantly associated with good dietary practices. WHO recommends that health professionals work in health facilities during ANC follow up for pregnant women to provide dietary interventions with effective nutrition counseling, iron and folic acid supplements, antibiotics for Asymptomatic Bacteriuria (ASB), Tetanus toxoid vaccination, and other woman selective recommendations. This create great experiences throughout ANC and build the foundations for healthy motherhood [38]. Women's involvement in decision-making and consideration of them as active participants in improving their own health is an important marker for pregnant women's overall health and is an essential component of high-quality prenatal services [39].

This finding demonstrated that pregnant women who received health and nutrition information were more likely than their counterparts to implement optimal nutrition and health practice. This is in line with a study conducted in Guto Gida Woreda, East Wollega Zone, Ethiopia, which found a positive significant relationship between mothers' nutrition practices and information on nutrition and family size [40]. This finding is also confirmed by a study conducted in Egypt, which found that mothers value and believe the recommendations of medical practitioners on the "best" foods to consume and avoid during pregnancy. In this study, 405 pregnant women (76.6%) received information from health professionals. The explanation for this could be that most of the time, respondents viewed the source of nutrition and health information acquired from health care experts to be a reputable and trustworthy source, and as a result, they would gladly seek to change their nutrition and health habits. Providing credible nutrition information to pregnant women may serve as a foundation for optimal nutrition and health practice.

The overall optimal nutrition and health practice of pregnant women in the study area was low, according to the findings.

Occupation (both respondent and husband), educational status of the husband, gravida, Antenatal care visit, and having health and nutrition information were all found to be independent predictors of optimal nutrition and health practice. According to the study's findings, the researcher should recommend that the district health office, health care professionals, health extension workers, and other responsible stakeholders strengthen the ENA-BCC message to improve optimal nutrition and health practice and alleviate the associated factors.

[Crossref]

Citation: Gebremichael MA, Reta AE, Teshome MS, Lema TB (2022) Nutritional and Health Practice and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women Based On Essential Nutrition Action Frame Works, In Ambo District, Ethiopia. J Nutr Food Sci. 12:861

Received: 12-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. JNFS-22-15847; Editor assigned: 14-Apr-2022, Pre QC No. JNFS-22-15847; Reviewed: 28-Apr-2022, QC No. JNFS-22-15847; Revised: 17-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JNFS-22-15847; Published: 25-Jun-2022 , DOI: DOI: 10.35248/2155-9600.22.12.861

Copyright: © 2022 Gebremichael MA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.