Journal of Yoga & Physical Therapy

Open Access

ISSN: 2157-7595

ISSN: 2157-7595

Research Article - (2021)

The National Institutes of Health estimate that 25.3 million American adults suffer from daily pain, a condition more common with aging, affecting quality of life as well as productivity. This pilot study investigated whether chair yoga (CY) improves chronic pain in home care patients and reduces the need for opioids. Methods: Participants were patients of Visiting Nurse Home and Hospice (VNHH), a home healthcare agency serving the state of Rhode Island, and identified as having chronic pain. Upon consent, a pre-intervention survey was conducted assessing previous yoga exposure, baseline demographics, perceived pain, and prescription pain medications. Seven homebound patients consented to CY participation. Participants engaged in 15-60 minutes of one-on-one chair yoga over six weeks tailored to individual ability levels. A post-survey was conducted after the final CY session assessing identical measures as the pre-survey. Paired t-test was used to assess statistical significance of data collected. Results: The average perceived pain utilizing analog scale was rated 7.71 out of 10 initially. After six weeks of CY intervention, the average pain score decreased by 4.5 (7.33 v. 2.83, p = 0.01). No patients reported adverse effects or increase in pain during the intervention period. Further, no patients required an increase in pain medication during or after the CY intervention. Conclusion: This pilot study demonstrates a role for complementary alternative medicine in home care patients with chronic pain. Low-risk routines such as CY offer an accessible option that may complement traditional therapies for patients that are unable to leave their homes.

Chronic pain; Chair yoga; Home care, Complementary therapies; Mind-body therapies

The National Institutes of Health estimate that 25.3 million American adults sufferfromdaily pain. Pain [1] is a personal and subjective experience that no test can measure withprecision. Chronic pain is often defined as pain that persists longer than three months, or past the timefornormal healing, and may arise from an injury or illness but many times the cause is notclear.[2]Chronic pain becomes more common with aging and can affect quality of life as wellasproductivity for many Americans. Annually, chronic pain accounts for an estimated $635billionin costs for treatment and lost productivity in the United States. [3] Optimal treatment plansaretailored to an individual patient with the goal of reducing pain and improving function sodailyactivities may resume.[2] One of the current mainstays of treatment for pain includesopioids analgesics such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, and combination products. Patients withchronicpain often require long-term treatment. Even when prescribed by a physician, regular useofopioid drugs may lead to dependence, addiction, overdose, and death. In 2018, RhodeIslandalone reported 267 opioid overdose deaths. [4] Alternative options are available forpatientsexperiencing chronicpain.Mind and body practices, such as yoga and meditation, have increased in popularityinrecent years as types of complementary health approaches for many Americans. [5] Symptomsofpain that are not consistently addressed by conventional treatments may be mitigatedbycomplementary approaches and lessen the risk of complications associated with many oftheprescription drugs used for pain. Yoga is a practice that has become increasingly popularinhealth and overall wellness. The practice has been studied in otherwise healthy individuals foritsbeneficial effects on depression, anxiety, stress, and pain. [6-8] many individuals could benefitfromthe effects of yoga but may not perceive themselves to be in adequate.

Condition to participate in the exercise as a result of safety concerns associated with certain comorbid medicalconditionsand general frailty of many older adults. Chair yoga (CY) offers a solution as a modifiedpracticethat invites individuals seeking an adaptive, low-risk routine for better wellnessoutcomeswithout fear for safety concerns associated with many other recommendedexercises.A recent pilot study examined whether CY compared to a Health EducationProgram(HEP) led by health care providers could have an immediate and sustained effect on painandphysical function in older adults with osteoarthritis. Both interventions consisted oftwiceweekly, 45-minute sessions in a South Florida senior center. Participants randomly assignedtothe CY group engaged in four main components: physical postures, breathing, deeprelaxation,and meditation while utilizing the support of a chair. Demographic information andphysicalmeasures were collected at baseline, the midpoint, 8 weeks at completion of the intervention,and1 and 3 weeks post intervention. After 8 weeks, CY participants were given a manualwithinstructions and pictures for continued yoga practice at home. All measures were completedonpaper by participants using Likert scale responses, which were summed to obtain anoverallscore for each measure at each data point.

The CY group showed greater reduction inpaininterference over 8 weeks (p = 0.010), sustained through 3 months (p = 0.022) compared totheHEP group. The study results support the use of a CY program to reduce pain interferenceineveryday living for patients with osteoarthritis. [9] Most recently, a pilot study wasconductedevaluating the effects of chair yoga versus chairbased exercise in 18, community-dwelling,olderadults with osteoarthritis. The investigators found no significant difference in thetwointerventions, though both improved physical function and mobility after the 8-weekstudyperiod. [10] To date, existing research examining the relationship of yoga or CY towellnessoutcomes has been conducted in community-dwelling, older adults.This study was designedspecifically to include home care patients that may not have the means or will to attendacommunity center. Home care services include a broad range of support to meet the needstopatients whose capacity for self-care is limited because of injury, chronic illness, disability,andother health conditions. In 2015, about 4.5 million Americans received services fromhomehealth agencies and 1.5 million receiving hospice services. Although people of all agesmayrequire such services, the risk of needing assistance increases with age and the numberofAmericans over age 65 is projected to increase by 84% by 2050.[11] Our patients at VisitingNurseHome and Hospice (VNHH) of Portsmouth, RI are home-bound for varying diagnosesincludingchronic pain and require a considerable amount of support to leave their homes withexcursionslimited almost exclusively to doctor visits. Pharmacists are an integral component oftheinterdisciplinary care team at VNHH by conducting medication evaluations ofpatientsundergoing transitions in their care, and offering prescription, nonprescriptionandcomplementary therapy recommendations. The aim of this study was to investigatewhetherbringing CY to the patient in the comfort of his or her own home could eliminate barriers,suchas transportation, to improve pain and reduce medicationusage.

Design

Data collection occurred prospectively. Secure software at VNHH containingactivepatients and their associated diagnoses was utilized to identify eligible patients. Due to thenatureof the intervention, investigators and participants wereunblinded.

Setting

All study patients were actively on service with VNHH. VNHH is an independent,non-profit home health agency that provides nursing, rehabilitation therapies, and palliative careandHospice services throughout the state of Rhode Island. The primary investigator met withindividuals one-on-one so that patients did not need to leave their homes. Patients ofVNHH

were able to practice CY utilizing personal chairs and recliners from their homes asequipmentand did not need to purchase or provide anythingadditional.

Participants

Home care patients of all ages with a diagnosis of chronic pain were eligibleforinclusion. Case managers referred select patients expressing an interest in meeting withtheprimary investigator for pharmacist and CY consultation. Patients were excluded if theyhadrecent surgery within the last 3 months. A total of seven eligible patients were enrolledandconsented to CY participation. One patient was excluded for having undergone recentspinalsurgery.

Intervention

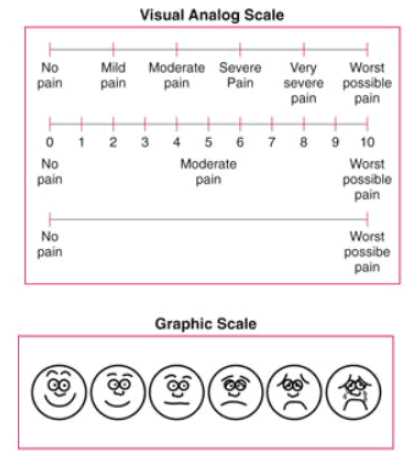

Upon identification, the primary investigator scheduled one-onone visits with alleligibleparticipants to engage in discussion about the study and to ensure understanding beforeinformedconsent was obtained to continue. Upon consent, a pre-intervention survey was conducted bythelead investigator. The survey assessed baseline demographics: age, gender, previousyogaexposure, current prescription pain medication usage, pain assessment, and past medicalhistory.Pain was assessed utilizing a paper pain analog scale (Appendix 1) ranging from zero to ten,withzero described as no pain at all and ten as the worst pain imaginable. This validatedscalesubjectively assesses chronic pain in both number as well as graphically, using facialexpressionssuch as smiling (no pain) to crying (worst possible pain). Further, a medicationreconciliationwas conducted by the pharmacist investigator to compare patient reported use andelectronicmedical records including medications used for pain. The survey also as sessedparticipant’sperceptions of yoga as a positive experience for overall wellness. After completing theinitialsurvey, the lead investigator engaged participants in 15 to 60 minutes of one-on-one chairyogatailored to individual ability levels and range of motion. The lead investigator underwent200hours of training to earn certification as a qualified yoga instructor two years prior tothisinvestigation. Yoga sessions were repeated once weekly for a total of six weeks witheachparticipant during the winter of 2019. Participants were provided a chair yoga handoutwithimages and encouraged to practice on their own between sessions. A post-survey wasconductedafter the final chair yoga session assessing identical measures as the pre-survey. Pairedt-testwas used to assess differences in pain score and quality oflife.

Appendix 1

1.On a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 meaning no pain and 10 meaning the worse pain you can imagine, how much pain are you having now?

2. Related to your prescribed pain medication, how often are you taking?

Main OutcomeMeasures

The primary study outcome measures were pain scores and pain medicationusage.

Seven patients were enrolled in this pilot study. Participants were primarily female,with71.4% over 65 years of age. The number of participants having CY exposure prior to the startofthe study was low at 28.6%. Average perceived pain was rated as 7.71 out of 10 initiallywithonly 28.6% reporting no use of prescribed pain medications prior to and during theCYintervention. Of the remaining 71.4% of patients taking pain medications, the majorityweretaking an opioid. Additional baseline characteristics were collected with percentages ofeachcharacteristic (Table 1). Concluding the six weeks of CY intervention, one patient was losttofollow up and data was not included in analysis for this participant. Of the remainingsixparticipants, the average pain score decreased by 4.5 (7.33 v. 2.83, p = 0.01). Nopatientsreported any adverse effects or increase in pain during the intervention period. of note,nopatients required an increase in their pain medication regimen during or after theCYintervention.

| Age range | 30 – 49 | 2 (28.6%) | |

| 50 – 65 | 0 (0%) | ||

| 65 – 79 | 2 (28.6%) | ||

| 80+ | 3 (42.8%) | ||

| Gender | Female | 6 (85.7%) | |

| Male | 1 (14.3%) | ||

| Previous Yoga Exposure | Yes | 2 (28.6%) | |

| No | 5 (71.4%) | ||

| Prescription Pain Medications | Yes | Oxycodone or combination | 4 (57.1%) |

| Gabapentin | 4 (57.1%) | ||

| Morphine | 1 (14.3%) | ||

| No | 2/7 (28.6%) | ||

| Past Medical History | Anxiety | 6 (85.7%) | |

| Arthritis | 5 (71.4%) | ||

| Depression | 4 (57.1%) | ||

| Insomnia | 4 (57.1%) | ||

| Cancer | 1 (14.3%) | ||

| Average Pain | 7.71 (n = 7) | ||

Table 1. Baseline Demographics

This study supports previous research utilizing complementary health approachesandbroadens the patient population that may benefit by including home bound patients, a groupnotincluded in CY studies to date. Previous studies analyzing the impact of CY on patientswithpain fail to address patients that are unable to attend community centers.[9,10] Group CYsessionswere initially considered for this research; however, the primary reason for choosingone-on-oneengagement with patients was to reduce aforementioned barriers and potentiallyincreasesustainability post-intervention. If patients initially start CY in the comfort of their ownhomes,our research team theorized that patients would be more apt to continuingexercisesindependently after the study’s conclusion. Further, our study utilized pharmacistdeliveredCYallowing for the unique assessment of pain therapy prior to and after theintervention.

A limitation to this study was the small sample size of patients. Due to time constraintsofthe lead investigator, additional patients expressing interest in participating after theprespecified study period were unable to be included in the initial pilot. Additional certifiedyogainstructors leading CY sessions would lend for more patients receiving this valuableservice. Further, given the nature of home care, patients are spread out geographically leading togreatertime demands for travel for one investigator. However, as a result of the positive outcomesofthis pilot study, the expansion of CY services is ongoing at VNHH. A focus on improvedpainmanagement and quality of life postintervention could offer more insight into sustainabilityasthe service continues to expand, as this outcome measure was not assessed in the initialpilot.Last, this study evaluated outcomes pre and post intervention; however, lacked long termfollow up data. Though small, the statistically and clinically significant measured improvement inpainscores and anecdotal reports from patient are impactful to pharmacy practice (Appendix 2).

Appendix 2 – Participant Testimonials

“Thank you so much for teaching me yoga! I really appreciate the time you took with your busy schedule. I learned so much, especially breathing and to practice ways to control my anxiety, stress, and chronic pain! I will always be grateful to you for teaching me ways to help control the pain I live with every day. Though my pain will never go away I’m happy to have learned ways to deal with it. Thank you so much for being patient with a beginner and for being so kind. Wishing you all the best!”

“I think if I continue with the exercise regime and some of my old marine corp exercises it could be good.”

“Definitely helps with panic, distracts the mind from pain, slept better, significant reduction from pain. Sometimes after yoga I want to take a nap not because I'm tired but because I'm relaxed. I know it’s not a cure but it definitely works. I'm a believer now, I even told my surgeon. I believe it will benefit others if they're open to try. Some people are stuck with the idea that opiates are the only cure, the answer to everything. I know that they do help to reduce pain and help with quality of life but it angers me that they won't consider alternatives.”

“Really enjoyed working with you and not just sitting around watching TV but moving while doing something. Wonderful! Fantastic!”

“This has been wonderful to me and it's nice to sit and talk with you. My QoL has declined because I’ve had a tough year but I was able to get up and vacuum yesterday without much pain and that made me happy.”

“I’ve enjoyed these visits very much. It is helpful that you are a pharmacist and can answer questions as well.”

“I feel relaxed and want to take a nap now. Your voice is very calming. The words you use and way you speak is thoughtful”

Pre-intervention, patients reported a 7.33 on the pain scale which translates to “very severepain”.Post intervention, patients reported a 2.83 translating to “mild pain”. For patients livingwithchronic pain, the elimination of pain may not be a realistic goal, yet a reduction in painintensityand improved quality of life may be attainable with adjunctive therapies such as CY. Withmoreproviders considering complementary health approaches such as CY services for theirpatients,barriers limiting more patients from receiving this intervention can be addressed for larger,moregeneralizable studies in the future. As the role of pharmacists continues to expand acrossvariouspractices, pharmacists are an integral part of the evaluation of pain managementregimens,ensuring the safety and wellbeing of patients. Pharmacists are the most accessiblehealthcareprofessionals and can have a direct impact on reducing opioid usage in the midst of ournation’sepidemic. Though our research did not detect a reduction in opioid usage over 6 weeks,therewas also no increase in pain medication across all patients. As research in the areaofcomplementary and alternative medicine evolves, safer treatments for patients with ailmentssuchas chronic pain should be encouraged where the benefit of mind and body practices hasbeendemonstrated.

This pilot study demonstrates the potential for positive outcomes withcomplementaryhealth approaches in homebound patients with chronic pain. CY is an accessible,adaptivepractice for patients seeking low risk routines. When tailored to individual patients, CYmayimprove pain scores and supplement traditional pain therapies.

This research was supported by the University of Rhode Island College of PharmacyandVisiting Nurse Home and Hospice of Portsmouth, RI. The author thanks colleagues Dr.VirginiaLemay, Dr. Katherine Orr, Dr. Kristina Ward, and Dr. Lisa Cohen from the University ofRhodeIsland as well as Dr. Madeleine Ng from Visiting Nurse Home and Hospice whoprovidedinsight and expertise that greatly assisted the research.

Citation: MargrafA and LemayV(2020) Pharmacistledchairyoga inhome care patientswithchronic pain.J YogaPhys Ther 10:S2. 316. Doi: 10.35248/2157- 7595.2020.10.S2.316

Received: 04-Nov-2020 Accepted: 09-Jan-2021 Published: 16-Jan-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2157-7595.11.s1.321

Copyright: © 2020 Margraf A and Lemay V, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.