Journal of Women's Health Care

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0420

ISSN: 2167-0420

Research - (2022)Volume 11, Issue 8

Purpose: Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and endometriosis are characterized by recurrent abdominal pain and interfere with quality of life. This study aimed to compare the association between affect and abdominal symptoms in endometriosis, IBS, and healthy controls (HC) using the Experience Sampling Methodology.

Methods: We included 34 endometriosis patients, 26 IBS patients and 55 HC. All participants were non-pregnant, ≥ 18 years. For seven days, participants completed up to 10 randomly assigned momentary assessments (MA) per day on a smartphone app. MA included abdominal symptoms and affective state on an 11-point Numeric Rating Scale. Associations were analyzed by linear mixed models.

Results: Abdominal pain and gastro-intestinal symptoms were comparable between IBS and endometriosis patients but mean scores were significantly higher compared to HC. Stress levels were comparable between all groups. However, endometriosis patients reported higher scores for ‘feeling dispirited’ and lower scores for positive affect compared to IBS and HC. In all groups, abdominal symptoms and affective symptoms seemed associated with functional limitation in daily life. However, direct associations between abdominal pain and affective symptoms seemed stronger in IBS and endometriosis patients compared to HC.

Conclusion: There is a large overlap of patient-reported somatic and affective symptoms in IBS and endometriosis. By use of the ESM, it is possible to analyze direct associations between somatic and affective symptoms in individual patients, potentially providing self-insight in coping styles and more individualized and tailored treatment.

Pain, positive affect, negative affect, momentary assessment, experience sampling method, irritable bowel syndrome, endometriosis.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and endometriosis are two common diseases characterized by recurrent abdominal pain with often severe consequences for quality of life [1]. The etiologies of the diseases are uncertain, but a multifactorial pathophysiology has been proposed for each of them. Validated tests based on biological markers for diagnosis are not available for either disease, and diagnosis often relies on descriptive symptom-based diagnostic criteria. Likewise, disease-severity is mainly defined by patientreported symptom experience.

Many studies have examined the two conditions separately, but the literature on the associations and overlap between endometriosis and IBS is sparse, although it is increasing. It is well-known that patients with endometriosis frequently have gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms [2]. For example, in a cross-sectional study up to 69% of endometriosis patients experienced nausea accompanying pain, and 50% reported relief of their pelvic pain after a bowel movement. Several other studies reported that women with endometriosis have a twofold risk to also fulfill the diagnostic criteria for IBS, while in women initially diagnosed with IBS, some studies reported a threefold risk of having an endometriosis diagnosis [3]. Whether this overlap should be regarded as two separate disorders occurring concomitantly in the same individual, or as uncertainty about the true diagnosis due to unknown underlying pathologies, is not yet clear.

A common feature in both IBS and endometriosis is central sensitization in which contributing factors such as psychological stressors are present. Hence, psychological diseases like depression and anxiety disorders occur more frequently in these conditions [4]. As in functional somatic syndromes in general, an integrated multidisciplinary approach is suggested in patients’ management to achieve an adequate diagnostic workup and a personalized therapy, in order to target symptom severity, complexity and treatment resistance due to fragmented trajectories [5]. For this purpose, we previously developed an electronic smartphone-based patient-reported outcome measure specifically for the use of the Experience Sampling Methodology (ESM) in both populations with endometriosis and IBS (MADE ANONYMOUS). ESM is a momentary assessment method collecting repeated measurements randomly during the day, concerning the current symptom state in the natural environment of the subjects. These repeated in-the-moment assessments result in an individual pattern of symptoms and provide insight into the complex interplay between longitudinal symptom formations and possibly associated daily life factors like psychological stressors.

This study aimed to compare the association between psychological factors and abdominal symptoms, and their interaction with limitations in daily activities, in patients with endometriosis, patients with IBS and healthy controls (HC) by using the ESM.

This study uses data from two separate observational studies that were executed as part of validation projects of the ESM tool. Both studies were approved by the medical ethics committee and were executed according to the tenets of the revised Declaration of Helsinki (64th World Medical Association General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil; October 2013).

Study participants

Both patients with endometriosis and IBS were recruited at the outpatient clinics, a secondary/tertiary referral centre. Furthermore, endometriosis patients were recruited by the Dutch Endometriosis Foundation (Endometriose Stichting). The diagnosis of endometriosis was established by physical examination, imaging techniques, or laparoscopy. Patients reported endometriosisrelated complaints (Dysmenorrhoea, Pelvic pain, or Dyspareunia) on average at least one day per week in the last 3 months. Patients were excluded in case of any other organic explanation for chronic pelvic pain besides endometriosis. IBS patients were diagnosed according to the Rome IV criteria [6]. Reason for exclusion in IBS was abdominal surgery in the past (except for uncomplicated appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and/or hysterectomy). HC were recruited through advertisements by social media. Controls were eligible when not reporting any (present or past disorder associated with) chronic pelvic pain. Both patient groups and HC consisted of non-pregnant women, aged 18 years or older, who understood the Dutch language and were able to utilize the ESM application. All subjects gave written informed consent prior to participation.

Data collection

At baseline, patients were asked to fill in an electronic clinical case report form (eCRF) concerning demographic information and medical history in Castor electronic data capture [7]. During the 7-day study period, subjects completed repeated real-time questionnaires using the ESM tool.

ESM tool

All participants downloaded the smartphone application “MEASuRE” (Maastricht Electronic Abdominal Symptom REcording) on their smartphone, which contained either an endometriosis- or IBS-specific ESM questionnaire that was previously developed (MADE ANONYMOUS). Subjects were instructed to carry their smartphone with them during the study week and to complete the real-time questionnaires as often as possible. The MEASuRE application was set to send out an auditory and text signal 10 times a day at random moments between 07:30 AM and 10:30 PM, with intervals of at least 15 minutes and a maximum of 3 hours. These real-time assessments contained questions about somatic symptoms, psychological symptoms, contextual or social information, and the use of food and medication.

For this study, only overlapping data in both questionnaires regarding abdominal pain and psychological factors were analyzed. The questions were identical between the different moments during the day and are scored on an 11-point Numeric Rating Scale (0= not at all to 10= very severely). Without any response within 10 minutes after a notification, a questionnaire became unavailable and considered as missing data afterwards.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 25. Continuous outcomes were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. In the case of normal distribution, the mean and standard deviation (SD) are presented. In case of non-normal distribution, the median and interquartile range (IQR) are presented. Data were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA in the case of ordinal data and the chi-square test for categorical and dichotomous data. Turkey’s HSD post-hoc tests were performed in case of a significant difference for means or medians between the groups. To exclude the effect of differences in compliance between subjects, mean scores per participant were calculated before analyzing an average group score. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Associations between somatic and psychological symptoms were analyzed by using linear mixed models as ESM data are based on a hierarchical, multi-level structure with repeated measurements (level 1) nested within days (level 2) and within-subjects (level 3). All models are based on random intercept and an autoregressive (AR(1)) covariate structure for repeated measures.

Patient characteristics

Table 1 shows the patient characteristics of 55 healthy controls (HC), 26 IBS patients, and 34 endometriosis patients. HC were significantly younger and had a lower BMI compared to IBS and endometriosis patients. More endometriosis patients reported a history of uncomplicated abdominal surgery (68%) compared to IBS patients (15%) and HC (16%). The use of (contraceptive) hormones was not significantly different between the three groups. On average, 65% of endometriosis patients reported the use of pain medication during the study, compared to 19% of IBS patients and 11% of HC (p<.001). The use of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol or other addictive substances was not significantly different between groups.

| HC (n=55) |

IBS (n=26) |

E (n=34) |

p- value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Median [IQR]) | 25 [4] | 28 [29] | 35 [10] | .002 |

| BMI (Median [IQR]) | 22.0 [3] | 24 [4] | 24.5 [7] | .043 |

| History of abdominal surgery (n (%)) | 5 (16) | 4 (15) | 20 (68) | <.001 |

| Use of hormones (n (%)) | 38 (69) | 14 (54) | 25 (74) | .247 |

| Use of caffeine (n (%)) | 43 (78) | 24 (92) | 24 (71) | .118 |

| Smoking (n (%)) | 2 (4) | 4 (15) | 5 (15) | .117 |

| Use of alcohol (n (%)) | 32 (58) | 14 (54) | 9 (27) | .097 |

| Use of drugs (n (%)) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | .301 |

| Use of painkillers (n (%)) | 6 (11) | 5 (19) | 22 (65) | <.001 |

*Ordinal data were tested using Kruskal-Wallis. Dichotomous data were tested using chi-square. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. HC = healthy control; IBS = irritable bowel syndrome; E = endometriosis; IQR = interquartile range; n = number of patients

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

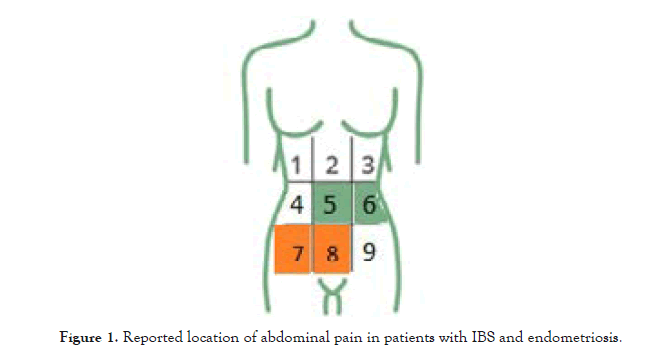

For abdominal pain, momentary assessments contained a question regarding nine abdominal locations, in which the selection of more locations was possible. Figure 1 shows significant differences in the frequency of reported locations of abdominal pain for IBS compared to endometriosis patients. This figure shows that IBS patients (green) were more likely to experience pain in the umbilical region (region 5) and on the left abdominal side (region 6) compared to endometriosis patients (orange). Endometriosis patients were more likely to experience pain in the lower abdomen/pelvic area (region 8) and on the lower right side of the abdomen (region 7) compared to IBS patients. Pain in regions 1-4 and 9 were not experienced differently between IBS and endometriosis patients.

Figure 1:Reported location of abdominal pain in patients with IBS and endometriosis.

Associations between “limitations in functioning” and somatic symptoms

During momentary assessments, patients were asked to complete the question of whether they feel limited in their daily activities because of their complaints. Mean (SD) scores for feeling limited (on a scale from 0-10) were 2.51 (2.89) for endometriosis, 1.34 (2.12) for IBS and 0.23 (0.95) for HC. Table 2 shows the association between somatic symptoms and the experience of feeling limited because of complaints in that very moment. In this table estimates show a Beta-coefficient which represents the direction (positive or negative) of the association. Abdominal somatic symptoms were associated with the feeling of being limited in all groups, except for experiencing abdominal distension in the healthy control group. Although differences in associations between groups were not tested, associations of feeling limited because of gastro-intestinal symptoms seemed less strong for healthy controls.

| Symptom score, Mean [SD] |

HC (n=55) |

IBS (n=26) |

E (n=34) |

F-test p-value |

Posthoc IBS vs E p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 0.22 [0.33] | 2.31 [1.46] | 2.97 [2.33] | <.001 | .198 |

| Bloating | 0.67 [1.00] | 3.64 [1.74] | 2.99 [2.32] | <.001 | .291 |

| Abdominal distension | 1.38 [1.56] | 4.84 [1.48] | 3.44 [2.50] | <.001 | .014 |

| Urge for defecation | 0.45 [0.50] | 1.54 [1.25] | 1.18 [1.37] | <.001 | .365 |

| Nausea | 0.15 [0.27] | 0.76 [0.99] | 1.00 [1.97] | .003 | .681 |

* Significances were tested using Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA. Posthoc analyses were performed using the Tukey-Kramer correction for unequal groups. To exclude the effect of differences in compliance between subjects, mean scores per participant were calculated before analyzing an average group score. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. SD = standard deviation, HC = Healthy control, IBS = Irritable bowel syndrome, E = endometriosis.

Associations between “functional limitations” and affect

Table 3 shows the association between affective symptoms and the experience of feeling limited in daily activities because of complaints. In endometriosis and IBS patients, both positive and negative affective symptoms were significantly associated with the experience of feeling limited. For HC, these associations seemed less strong or not significant.

| Symptom score, Mean [SD] |

HC (n=55) |

IBS (n=26) |

E (n=34) |

F-test p-value |

Posthoc IBS vs E p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeling stressed | 1.54 [1.53] | 1.26 [1.40] | 2.18 [2.35] | .110 | .120 |

| Feeling dispirited | 0.95 [1.28] | 0.71 [0.22] | 2.01 [2.15] | .002 | .005 |

| Feeling relaxed | 6.41 [1.38] | 6.39 [1.28] | 5.38 [1.54] | .002 | .019 |

| Feeling cheerful | 6.86 [1.13] | 6.28 [2.09] | 5.23 [1.92] | <.001 | .040 |

*Significances were tested using Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA. Posthoc analyses were performed using the Tukey-Kramer correction for unequal groups. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. SD = standard deviation, HC = Healthy control, IBS = Irritable bowel syndrome, E = endometriosis.

Table 3. Average psychological symptom scores for IBS vs endometriosis patients vs HC, measured in real-time, several times a day. At first average scores per participant were calculated to exclude the effect of compliance.

Associations between abdominal pain and affect

Table 4 shows the association between abdominal pain and affective symptoms. In IBS and endometriosis patients, both positive and negative affective symptoms were significantly associated with abdominal pain, with the exception of feeling cheerful in IBS patients. In HC, “feeling dispirited” and “feeling cheerful” were also associated with abdominal pain but this association seemed less strong. For example, in IBS and endometriosis patients a one point increase in feeling dispirited was on average associated with a significant increase of 0.15 points in abdominal pain. For HC this increase in abdominal pain was only 0.05 points. However, differences in associations between groups were not statistically tested (Table 5 and 6).

| Symptom score, Estimate (SE) |

HC (n=55) |

IBS (n=26) |

E (n=34) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 0.23 (0.02)*** | 0.18 (0.02)*** | 0.34 (0.03)*** |

| Feeling bloated | 0.05 (0.01)*** | 0.15 (0.02)*** | 0.26 (0.03)*** |

| Abdominal distension | 0.03 (0.02) NS | 0.15 (0.03)*** | 0.29 (0.04)*** |

| Urge for defecation | 0.03 (0.01)* | 0.16 (0.02)*** | 0.14 (0.03)*** |

| Nausea | 0.09 (0.03)*** | 0.26 (0.03)*** | 0.36 (0.04)*** |

*Estimates (SE) tested using linear mixed models with “limitation in functioning” as dependent variable and the somatic symptom as independent variable, corrected for repeated measures (AR1 covariate structure). SE = standard error; HC = healthy control, IBS = irritable bowel syndrome; E = endometriosis; *p<0.05; **p<0.01;***p<0.001; NS = not significant.

Table 4. Associations between “limitations in functioning because of complaints” and somatic symptoms.

| Symptom score, Estimate (SE) | HC (n=55) |

IBS (n=26) |

E (n=34) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feeling stressed | -0.01 (0.01) NS | 0.11 (0.03)*** | 0.18 (0.03)*** |

| Feeling dispirited | 0.05 (0.01)** | 0.15 (0.04)*** | 0.20 (0.03)*** |

| Feeling relaxed | -0.02 (0.01)** | -0.10 (0.02)*** | -0.15 (0.03)*** |

| Feeling cheerful | -0.02 (0.01) NS | -0.13 (0.03)*** | -0.26 (0.04)*** |

*Estimates (SE) tested using linear mixed models with “limitation in functioning” as dependent variable and the psychological symptom as independent variable, corrected for repeated measures (AR1 covariate structure). SE = standard error; HC = healthy control, IBS = irritable bowel syndrome; E = endometriosis; *p<0.05, **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; NS = not significant.

Table 5. Associations between “limitations in functioning because of complaints” and affect.

| Symptom score, Estimate (SE) | HC (n=55) |

IBS (n=26) |

E (n=34) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feeling stressed | 0.01 (0.01) NS | 0.10 (0.04)* | 0.12 (0.03)*** |

| Feeling dispirited | 0.05 (0.01)*** | 0.15 (0.06)* | 0.15 (0.03)*** |

| Feeling relaxed | -0.00 (0.01) NS | -0.09 (0.03)** | -0.06 (0.02)** |

| Feeling cheerful | -0.02 (0.01)** | -0.06 (0.04) NS | -0.14 (0.04)*** |

*Estimates (SE) tested using linear mixed models with abdominal pain as dependent variable and the psychological symptom as independent variable, corrected for repeated measures (AR1 covariate structure). SE = standard error; *p<0.05, **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; NS = not significant.

Table 6. Associations between abdominal pain and affect.

This study aimed to compare the association between affect and abdominal symptoms in IBS patients, endometriosis patients and HC. In order to do this the ESM was used, which means that symptoms were scored in real-time, several times a day for a consecutive seven days in the patients’ daily life context. Even though 68% of endometriosis patients had already undergone surgery for their endometriosis in the past, and more endometriosis patients reported regular use of pain medication, abdominal pain scores were not significantly different between IBS and endometriosis patients. The location of abdominal pain was slightly different as IBS patients reported more pain in the umbilical and left-sided region of the abdomen and endometriosis patients reported more pain in the pelvic and right-sided region of the abdomen. Gastrointestinal symptoms like bloating, urge for defecation, and nausea were just as common in IBS patients as in endometriosis patients, making it difficult to clinically distinguish between both conditions based on a symptom level. Although endometriosis patients felt significantly more dispirited compared to IBS and HC, levels of perceived stress were not different between the groups. Surprisingly, endometriosis patients scored significantly lower on positive affective symptoms compared to IBS patients and HC, which may identify an important target concerning further therapeutic options for these patients.

Perceived limitations in daily activities, caused by symptoms, have an impact on health-related quality of life. In this study, the association between symptoms and the feeling of being limited by symptoms at that same moment was investigated. Results showed that endometriosis patients, IBS patients and HC experienced limitations in daily activities related to abdominal pain. Associations were also found for gastrointestinal symptoms like feeling bloated, abdominal distension, and nausea, however, these associations seemed less strong for HC. Associations between affect and the experience of feeling limited seemed to be stronger for endometriosis and IBS patients compared to HC, however statistical testing to compare groups was not performed. When looking at the direct association between abdominal pain and affective symptoms, in IBS and endometriosis patients positive and negative affective symptoms were associated with abdominal pain. In HC associations seemed less strong or were not significant, leading to the impression that disease related pain perception is interrelated with affective states.

As ESM measures both somatic and affective symptoms in real-time, direct associations can be calculated. In the current study, only direct and in-the-moment associations were analyzed, which means that no predictions can be made. In both IBS and endometriosis patients, chronic abdominal pain is thought to be multifactorial. Whether the impaired psychological well-being is primary or secondary to chronic pain is difficult to determine. However, in a short-term observational study, stress was not a short-term predictor for abdominal pain in patients with either endometriosis or IBS. Furthermore, in endometriosis patients, abdominal pain was associated with higher scores for feeling dispirited and stressed later on during the same day (MADE ANONYMOUS). Future studies should be performed to evaluate the longitudinal associations between abdominal pain and psychological factors in these patient groups.

As the results of this study were a product of two individual ESM studies, inclusion and exclusion criteria were slightly different between groups, and age and BMI were not matched between the three groups (MADE ANONYMOUS). HC had a significantly lower age and BMI, which could be explained by the fact that HC were recruited by advertisement in a University Hospital and were therefore likely to be medical students. Furthermore, in the original IBS study (MADE ANONYMOUS), male IBS patients and HC were included. To make the three study groups as homogenous as possible, we excluded the male participants of the IBS study.

As described previously, IBS patients might have an increased risk for endometriosis and endometriosis patients could have a higher risk for IBS [1,3]. In this study, HC, IBS, and endometriosis patients did not all undergo a laparoscopy to determine the presence or absence of endometriosis. Therefore, it could be possible that there were asymptomatic endometriosis patients in the healthy control group or symptomatic endometriosis patients in the IBS group. Reversely, the Rome IV criteria were not applied to endometriosis patients, and therefore the occurrence of IBS in the endometriosis group cannot be ruled out. As long as no biomarkers are available to confirm a diagnosis of IBS or endometriosis, it is difficult to confirm or exclude a diagnosis of these two conditions, since the results of descriptive studies show an overlap in both abdominal and affective symptoms [1,4,8]. Although mean scores for affective symptoms in this study were not statistically different between IBS patients and healthy controls, direct associations with abdominal pain seemed to be stronger in the IBS (and endometriosis) group. Furthermore, it seemed that IBS and endometriosis patients felt more limited in daily life due to either somatic or affective symptoms compared to HC. Therefore, it seems that affective states contribute to the somatic symptom experience and reduction of the somatic symptoms alone may not improve quality of life sufficiently enough [9]. Furthermore, in both IBS and endometriosis, central sensitization is described when pain becomes unresponsive to fragmented medical therapies. Thus, expanding to an individualized and targeted treatment trajectory including contextual factors and affective states may enhance therapeutic quality and reduce treatment refractoriness [10,11].

The current study shows no differences in abdominal pain and other gastrointestinal symptoms between endometriosis and IBS patients, but significantly higher scores for feeling dispirited and lower scores for positive affect in endometriosis patients compared to IBS and HC. Abdominal pain was directly associated with affect in both IBS and endometriosis patients and these direct associations seemed less strong for HC. Somatic and affective symptoms were associated with functional limitations in both patient groups and seemed less strong or not significantly associated in HC. This study highlights the importance of investigating direct associations between somatic symptoms and affect, and the limitations in daily activities that patients may experience due to complaints. By using ESM, it is possible to analyze these direct associations due to longitudinal measurements rather than comparing average (or retrospectively reported) symptom scores. Associations may give more information concerning the impact that symptoms may have on symptoms and on patients' daily life. ESM may help to provide self-insight in personal coping styles and could guide to more individualized and tailored treatment.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Citation: Van Barneveld E, et al. (2022) Psychosomatic Interactions in Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Endometriosis, and Healthy Subjects: An Experience Sampling Method study. J Women's Health Care 11(8):595.

Received: 19-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. JWH-22-18486; Editor assigned: 21-Jul-2022, Pre QC No. JWH-22-18486; Reviewed: 18-Aug-2022, QC No. JWH-22-18486; , Manuscript No. JWH-22-18486; Published: 24-Aug-2022 , DOI: 10.35248/2167-0420.22.11.595

Copyright: © 2022 Van Barneveld E. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.