Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy

Open Access

ISSN: 2161-0487

ISSN: 2161-0487

Research Article - (2019)Volume 9, Issue 2

Much has been written about attachment styles and mental health. This paper seeks to build a model of the strengths of resilience leading to recovery within the dismissive and preoccupied adult insecure attachment styles. This model will then be discussed utilizing composite case material for the purposes of supporting clinicians treating individuals with insecure attachment styles.

Resilience; Recovery; Attachment; Attachment styles; Insecure attachment

We learn how to be human from our connection with other humans. Particularly powerful connections with other human beings become the foundation for our attachments, ways in which humans learn to soothe and organize themselves through the presence of others. Much study has been done on what are considered the optimal attachment circumstances for a fully integrated and functional person [1-4]. This pattern of connection, termed secure attachment, has long been considered by many to be the pinnacle of healthy human development, with other patterns of connections being largely relegated to pathology and “not enoughness” in theory and research [5-7]. However, with roughly half the population falling into other types of attachment patterns, termed “ insecure ” , it is not possible that everyone without secure attachment is pathologically predestined. In fact, it is well known in the clinical world that those who do experience serious mental illness also have strengths and capacities that are unique, effective and powerful [8-10]. These individuals are not simply and wholly pathologized, they are complex and nuanced people. This paper seeks to explore the ways in which unique strengths and capacities are manifested in those with insecure attachment patterns utilizing composite case material.

Generally, the literature recognizes four discrete attachment styles, one secure and three insecure: avoidant, fearful and disorganized. These styles originated in the work of Bowlby and Ainsworth and their research on children’s attachment patterns with their parents, including Ainsworth’s Strange Situation research [2,11]. From these styles, several measures have been designed to determine attachment styles in the general population with fairly reliable interrater and reliability results [12,13]. Each childhood attachment style has a corresponding adult attachment style. Secure childhood attachment style becomes autonomous adult attachment style. Avoidant childhood attachment style becomes dismissing adult attachment style. Anxious childhood attachment style becomes preoccupied adult attachment styles and disorganized childhood attachment style becomes unresolved adult attachment style [14]. For the purposes of this paper, I will use the adult attachment style terms and concepts.

There is some ongoing discussion about the unresolved insecure attachment style. It was originally a research category created by Ainsworth and her assistants to house data instances that did not fit into autonomous, dismissing or preoccupied styles. Therefore, the unresolved attachment style is not truly a “category”, but rather a “catch all” that may be a group of diverse ways in which individuals coped with difficult attachment in much less likely ways [4]. Because of the inconsistent nature of the unresolved attachment style, in this paper I will examine only the two stable insecure categories. The two remaining insecure attachment styles, dismissing and preoccupied, have a set of predictable interpersonal and self-organizing patterns in the pattern below (Table 1) [15].

| Attachment Type | Patterns | Affiliated Questionnaire Statements |

|---|---|---|

| Dismissing | High avoidance | It is important for me to feel independent from others |

| Low anxiety | I am comfortable without close emotional relationships | |

| Values independence | It is very important for me to feel self-sufficient | |

| Low on trust | I prefer not to have others depend on me | |

| Values being alone | I do not disclose personal information to others that I am not close to | |

| Narrow emotional range | It is difficult for me to accept advice from others because their views are so different from mine | |

| I believe it is a waste of time to argue/disagree with others | ||

| I do not go to others when I am upset because I like to deal with problems on my own | ||

| Preoccupied | Low on avoidance | I want to be completely emotionally intimate with others |

| High on anxiety | I worry that others do not value me as much as I value them | |

| Craves intimacy | I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like | |

| Ruminates | I would like to spend more time with others, but they do not have enough time for me | |

| Desire merger | It takes a long time for me to become close to someone new | |

| Low self esteem | I am affectionate in my relationships with others | |

| When I disagree with others, I find that they are often defensive | ||

| I like to deal with conflict immediately, regardless of how long it takes to resolve the conflict | ||

| I cry easily |

Table 1: Self-organizing patterns of the insecure attachment styles.

While attachment styles as categories are the most generally understood conceptualization of attachment theory, there is some literature from Crittenden, a student of Ainsworth, which indicates that using discrete categories of attachment as a theoretical conceptualization was never the goal of Ainsworth’s work but instead was a useful research method with the ultimate aim being a spectrum rather than categorical conceptualization [4]. While this merits further attention, this paper will proceed with attachment styles as categories.

Insecure attachments result from early caregiver misattunement which leads to insecure attachment patterns and even attachment trauma. This interrupts or arrests a person’s ability to develop a secure attachment style [16-18]. The Adverse Childhood Events (ACES) body of research indicates that difficult things happening during childhood are relatively common in the general population and can lead to many poor physical and psychological outcomes later in life [19-21]. This research indicates that adverse childhood events may also be relatively common and which would lead to relatively common individuals with insecure attachment styles. This begs the question of how those individuals who experience these things are often able to lead satisfying lives, despite insecure attachment.

In her research of severely neglected and abused children who grew up to be self-reported successful adults in “Strong at the Broken Places”, Sanford’s investigation of these strengths suggested themes of doing a lot with very little and utilizing fantasy [22]. Those who have had difficult experiences also seem to find unique ways to adapt and cope with these experiences which are recognizable to clinicians and others who work in human services fields [23,24]. It would then follow that those who do not have secure attachment due to difficult early childhood events may have a particular type of strength that is worth investigating in order to better conceptualize how to support and treat individuals who are struggling.

Concepts such as “recovery” and “resilience” attempt to conceptualize these particular types of strength. They are newer ideas in the mental health lexicon and research than are ideas of insecure attachment, pathology, and serious mental illness. As such, they also need additional research. The concept of recovery is older and more researched and appears to be organized around stages and facets. The stages of recovery include Moratorium, Awareness, Preparation, Rebuilding and Growth [25] and the facets include Self-esteem, Empowerment, Social support and Quality of life [8,10,26]. A tool called the Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) to is being utilized in many community mental health programs. It incorporates and measures these ideas [27].

Working definitions

Self-esteem: Positive feelings and confidence about one’s self and identity.

Empowerment: One’s feeling of having authority to act.

Social Support: Care and assistance from other people.

Quality of life: a standard of health, comfort and happiness [8,26,27].

Resilience is a newer and less studied concept but appears to have overlap with the concept of recovery. A meta-analysis of resilience frameworks revealed very little universal consistency and reliability of the concept and suggested more research [28]. From that meta-analysis a few stronger models have arisen. First, themes of resilience were found to include overcoming difficulties, adjusting and adapting to the new, full recovery, mental immunity, and personal strengths [29]. Then, further research showed that resilience is a multi-dimensional process including dimensions such as self-efficacy, optimism, emotional regulation, adaptability and perceived social support leading to an increased capacity for successful coping through a sense of coherence [30,31].

Working definitions:

Self-efficacy: one’s belief in one’s ability and skills to act and succeed.

Optimism: hopefulness and confidence about the future or successful outcome.

Emotional regulation: person’s ability to effectively manage and respond to emotions.

Adaptability: being able to adjust to new conditions.

Perceived social support: One’s feelings and understanding of care and assistance from other people [24,29-33].

Incorporating the idea of resilience as a process with many themes and dimensions allows one to examine the possible types of capacities needed. I posit the following process capacities:

Capacity to detect internal or external threat.

Capacity to survive internal or external threat.

Capacity to re-organize the self after threat has resolved [16,24,29-37].

Facets of recovery and dimensions of resilience utilized within the process capacities

Various parts of resilience and recovery are used in the process capacities of resilience which build upon each other in order for an individual to survive stress and distress (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Parts of resilience and recovery.

Capacity to detect internal or external threat

Resilience’s concept of emotional regulation [30] and recovery’s concept of self-esteem [27] appear to be most useful in detection [8,27,30]. One would need a solid sense of self as valuable and worthy of protecting from threat and an ability to manage the immediate emotional response that may result from detecting a threat [7,18,38]. If individuals think they are not solid, integrated selves or are unworthy of care, they would be less likely to stay alert for threat. Similarly, if one is hypervigilant or emotionally dysregulated, threat detection would be compromised.

Survive the threat

Emotional regulation is also necessary in order not to become overwhelmed or underwhelmed by the experience of surviving a threat. Without an ability to manage emotion, one’s nervous system will over or under regulate. This leaves the person neurobiologically vulnerable and less able to access higher cortical functions [18,39].

Additional resilience concepts utilized in surviving the threat would include empowerment, self-efficacy, optimism and perceived social support (which is also a recovery facet). One needs to feel like they are not only capable and able to survive through self-efficacy but also allowed to survive through empowerment. One would need to feel both strong and skilled. They would need to have the optimism that the threat is overcomeable. Finally, in order to not become hopeless, one would have to believe that there was enough positive in the world worth surviving. Finally, feeling that there are other people who are there to support them through the threat in the form of perceived social support will help people survive the threat [8,30].

Reorganize the self after the threat has resolved

Some individuals have life experiences in which they feel as if threat is never resolved or in which they experience layers and sequences of threat. This could be objectively true but it can also be the result of hypervigilance and other limitations in processes of threat detection. This is important to note because an ongoing unresolved threat will impact one’s ability to reorganize. If one feels the threat never resolves, it will be highly difficult to re-organize [16,40,41]. For the sake of description, this discussion will assume the resolution of the threat.

In the process of reorganization, one would also need the resilience dimension of emotional regulation for similar reasons as in the previous processes: in order to access higher cortical function. Additionally, perceived social support helps people to utilize that universal seeking mentioned at the start of the paper. Humans have to organize and self soothe through the use of other human beings’ brains, minds and hearts [17,42].

In this process, two facets of recovery are also important: self-esteem and quality of life. Similar to the first process, detecting a threat, self-esteem would be required for one to feel they are worthy of being re-organized. Without it, one may not engage in this process at all and remain feeling disintegrated. Finally, one’s quality of life could include their living situation, general health, community, support around oppressed identities, and ability to financially support themselves. In other words, if the lower levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs are not being met, it is highly difficult to reorganize the self around self-esteem or actualization [43].

Each of these processes affects the other and the dimensions and facets of recovery and resilience within them will help support each capacity to the degree with which one is able to access them.

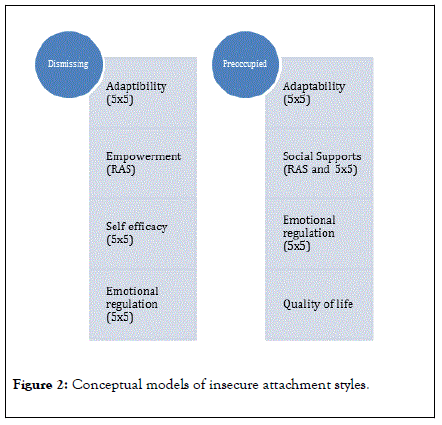

Each of the insecure attachment styles has uniquely increased or decreased capacity in each of these areas, leading to a particular type of resilience supporting their recovery from major mental illness (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Conceptual models of insecure attachment styles.

Dismissing style

A person with a dismissing attachment style is strongest in adaptability, empowerment, self-efficacy and emotional regulation.

Ellen is a sixty-seven-year-old cisgender woman of Polish descent. She is in her second marriage and struggles with feelings of worthlessness, depression and suicidality. She reports this has been true for as long as she can remember, even as a child. She was the third oldest of seven siblings and oldest girl She was often called upon to take care of her younger siblings because her parents were emotionally distant and worked many hours to support their family. She cannot remember any moments of warmth from either parent but reports that they “did their best” and “always kept food on the table”.

She married her high school sweetheart upon graduation and they had three sons together and lived in a small rural town where her husband was well known in the community as a leader. Ellen reports that her husband was regularly physically abusive and raped her on many occasions. She reports being told by her family that it was her job as his wife to fulfill her husband’s sexual needs and that she needed to manage this on her own. She spent many years enduring so she could “be a good mother and wife”. Finally, when her children were young adolescents, she reached out to local law enforcement who denied her help and she waited another two years before seeking a divorce whereupon the judge chastised her for abandoning her duties. She was ostracized by her community and her husband got full custody of their children.

Ellen then met another man who lived in a different community and they began dating. When the man moved out of state, he told her that she needed to come and live with him or he would find someone else. Ellen struggled to choose between staying and being able to continue to parent her sons during visitation or have her relationship and ultimately chose to move to the different state and marry the new man after asking each of her sons who encouraged her to be with her boyfriend. She reports that this is a choice she has always regretted and feels her relationships with her sons have never recovered.

When her parents were dying, her siblings asked her to move back to the community and care for them which she did until each of them died. She also cared for one of her younger sisters who took ill soon thereafter and also died. She reports receiving little help from her siblings during this time and not asking for any. Currently, she feels estranged from her husband, her community, her religion, her sons and her remaining siblings. She spends most of her days in her house and struggles to want to engage in any interpersonal activities because she feels exhausted, unmotivated and on the verge of collapse from heavy emotions.

Clinical interpretation: Someone with a dismissing attachment style identifies strongly with being independent and effective in the world without others. Because of the observer’s role that they often take in situations coupled with this independence, they feel able to manage most new situations. Their emotional regulation may also include constriction of affect in an overregulated way of trying to manage emotional experiences in a social setting, but this does not mean that they are not internally regulating or feeling big emotions. They just do not always have the desire or capacity to regulate them openly in the presence of others [3,15,16,44]. We see this in Ellen as she moved through her life; she is often enduring but rarely expressive.

Capacity to detect internal or external threat: A person with a dismissing attachment style would have a decreased (less sensitive or less accurate) ability to detect external interpersonal threats. This makes sense given that someone with a dismissing attachment style is more likely to avoid interpersonal interactions which may lead to distress and so would have less experience overall in threat detection by nature of having less opportunity. Ellen displays a pattern of decreasing social integration as she is rebuffed from an early age and throughout her life every time that she reaches out for assistance. Having less social support from her reference group leaves Ellen vulnerable to threat through not being able to detect it. This can be observed from her young marriage to an abusive man to her community shaming her and refusing her support. Ellen is less likely to be able to detect or problem solve her threats and so resorts to just enduring. Other types of external threat (systemic, political, resource) and internal threat detection may not be as affected. In fact, a person with a dismissing attachment style may be more able to detect them from having hung back and put themselves in the observer position in many circumstances. This is where the person with dismissing attachment style’s unique form of emotional regulation will come into play and help modulate affect in order to detect threats.

Capacity to survive internal or external threat: All four of this attachment style’s strengths can be utilized for this capacity. What are missing are perceived social supports and optimism. So, while someone with a dismissing attachment style is a strong survivor, they struggle to feel confident about the future or that there are other people around them willing to care for or support them. Someone with dismissing attachment style then may survive through sheer willpower and independence but find themselves mired in doubt about the survivability of the situation and feeling negative and resentful toward other people because of their perceived lack of social supports. Ellen demonstrates this with increasing acuity throughout her lifespan, also due to the traumatic and intense nature of the threats she survives.

Capacity to re-organize the self after threat has resolved: Someone with dismissing attachment style is weakest in their ability to re-organize after surviving a threat. Their one strength in this area, regulating emotions, is also limited through constricted affect which limits their capacity to engage outside social supports to help them to reorganize. Other people may just not be able to recognize the emotional need of this attachment style. Other weakness involved the perception of no social supports which is exacerbated by this constricted affect, limited self-esteem and limited positive feelings about quality of life. While someone with a dismissing attachment style feels they have self-efficacy, they may not feel as much self-esteem. In other words, they know they are capable but they question whether they are valuable or worthy. Because of this whole series of the resilience process, their quality of life may be compromised. Someone with dismissing attachment style struggles to rally themselves for reorganization after surviving a threat because they aren’t convinced that they as a person and their life is worth re-organizing.

Ellen went from one social situation to another with decreasing capacity to reorganize. First, she went from her family of origin with its lack of warmth and nurturing to her first husband who was abusive. After surviving the divorce from him, she sought reorganization in a new romantic connection but found that he was just as demanding and that she had disconnected from her children in order to connect with him. When she returned to her hometown to care for her family, her siblings did not connect with her in order to support and help her reorganize after the deaths of her family members and Ellen as a result of these many years of reorganization failure is in a collapsed state.

In sum, someone with a dismissing attachment style is a strong survivor through independence and willpower, able to detect environmental threats moderately well as a detached observer or avoid them entirely through their tendency to avoid interpersonal attachment but struggles with reorganization after the threat has resolved, with a vulnerability of collapsing without asking for help.

Preoccupied attachment style

A person with a dismissing attachment style is strongest in adaptability, social supports, empowerment and quality of life.

Angela is a 46-year-old cisgender woman of Irish Catholic descent living in a small rural town in New England. She is the youngest of five much older siblings and the only girl. Her father was a traveling salesman, her mother was a nurse and her brothers all worked construction during and right out of high school. Her family alternated between showering her with affection as the only girl and withdrawing their attention because they all worked long hours and had little in common with her. She anxiously sought out her brother and parents’ attention when she was able to get it and found herself lonely and a “people pleaser” when she entered school. She made many friends but felt unsatisfied with the intimacy of her friendships, often thinking it was her fault that she did not feel close enough to them.

In college, she began dating a highly intelligent man who had her choose between marrying him and raising their children and completing her own education. She chose to leave school and they had four children together in quick succession. Their second to youngest had special needs and Angela found herself consumed with caring for needs of her children, joining support and mommy groups and surrounding herself with people, usually with the same unsatisfied and anxious feelings. Her husband completed his education and got a job in which he travelled often, leaving Angela to care for the children (who she had begun homeschooling) and the house alone. She joined homeschool groups and ran children’s activities frequently and got to know many in the community.

As her children entered adolescence, her husband came home less and less frequently and eventually wrote her saying that he wanted a divorce and custody of all the children but the one with special needs. He had drained their bank accounts and left her without resources so she was unable to pay for a lawyer for their divorce and was left with only a small temporary alimony and child support to pay for her and her child with special needs to get an apartment. Having left school and the workforce years ago, Angela found herself unable to secure a job and fell into a deep depression. She frequently sought comfort and help from the friends she had made in her community but they quickly became overwhelmed by her deep need for intimacy and support from them and withdrew. Feeling rejected and alone, Angela struggles to care for her child, pines for her other children (who her ex-husband moved out of state with him) and is unable to find new connections in her community.

Clinical interpretation: A person with a preoccupied attachment style is able to read, express and manage their own emotions and adjust to new conditions until they become flooded by feelings of anxiety, rejection or unworthiness which then preoccupy their ability to do these things. Because they have strong social skills and a drive for connection, they are often able to make many friendships and other connections but struggle to feel that these connections are strong enough. Integrated in a social community, they find their quality of life to be generally good until they become overwhelmed. This is demonstrated with Angela above as she is able to move through various challenging life circumstances until she feels the strongest rejection of her husband’s demand for divorce and the ramifications of this which overwhelm her capacities and her social community.

Capacity to detect internal or external threat: In their search for connection and intimacy, individuals with preoccupied attachment styles frequently miss or misinterpret internal and external threats. They are overly sensitive to rejection or perceived lack of intimacy and so act upon threats that are not there. They also may overestimate the level of connection with another and so do not see threats that are there and continue interacting in unsafe ways in order to pursue intimacy and connection. Angela shows us this when she agrees to let go of her own education in order to marry a man who is distant throughout their marriage. She also overwhelms her social support system when she herself is overwhelmed and finds herself more hurt than before. This lack of self-esteem capacity is a foundational barrier to being able to detect internal or external threats.

Capacity to survive internal or external threat: Someone with a preoccupied attachment style has strength in surviving threats because of their emotional regulation skills, social supports and adaptability. Angela is able to navigate many stressful situations - parenting and keeping her house without the support of her partner, finding supports for herself and her children including the one with special needs for sustained periods of time by adapting herself and utilizing a large support network that she creates for herself. It is not until her system becomes overwhelmed that these capacities no longer endure.

Capacity to reorganize the self after threat has resolved: It can be the support networks that these individuals create for themselves that allow for stronger reorganization after a threat, but only if the support systems do not become overwhelmed with the needs of the individual with a preoccupied attachment style. This can sometimes happen when the individual is able to call upon a stronger emotional regulation capacity but it depends upon the situation the individual is recovering from and if their system is able to endure without disintegrating. Even if the individual temporarily is unable to regulate their emotions, once they are, the social support system is yet another part of their strength in reorganizing. This is demonstrated in the case of Angela who, if she is able to work on having connections without overwhelming others, has the social support system in place to help her reorganize herself more quickly than someone who does not have this support system.

Attachment theory is often taught to clinicians as ways to organize ideas around health and pathology in merely binary terms: secure attachment is healthy while insecure attachment leads to pathology. I would assert that this type of thinking is a false binary and that there is a wealth of nuanced information about resilience to be found within insecure attachment styles. This concept would lend itself to the development of clinical tools within a strengths-based perspective. Earned secure attachment is a gold standard goal for those with insecure attachment but the road there is admittedly difficult and regression to earlier attachment style behaviors and ways of thinking and feeling is common in the face of stress [18,45]. What if the conceptualization of the unique resilience and strengths of those with insecure attachment not only lit up a clear pathway to earned secure attachment but also highlighted the ways in which those with insecure attachment are perhaps stronger or more uniquely strong in ways that those with secure attachment are not? In the case of Ellen, a dismissing attachment style individual, recognizing that her collapse has resulted from years of over-utilizing a strong survival capability built from adaptability, empowerment, self-efficacy and a particular style of constricting emotional regulation would help a clinician to recognize and build upon Ellen’s strengths in order to shore up her less strong attributes such as optimism and social supports. Or in the case of Angela, a clinician could quickly ascertain that she is able to make many social connections once her psyche is given enough space and support around her sense of rejection and anxiety and that these social connections can form a strong foundation in her healing. This type of conceptualization would offer a more precise roadmap to clinicians that are not currently as effective or clear in the field and ways to health for the many individuals with insecure attachment styles that are not currently explored. To this end, further study of these ideas is warranted in order to increase our capacity to serve the millions of individuals with insecure attachment styles.

Insecure attachment styles yield not only challenges but also unique resilience and recovery abilities. With individuals diagnosed with serious mental illnesses often having higher rates of insecure attachment, understanding these strengths is vitally useful for clinicians assisting in their recovery. This paper provides an initial conceptualization for understanding these strengths and encourages additional investigation and research in order to create more accurate and refined models for clinical use.

Citation: Weise M (2019) Resilience and Recovery of Insecure Attachment Styles within Clinical Practice. J Psychol Psychother 9:359. doi: 10.35248/2161-0487.19.9.359

Received: 21-Dec-2018 Accepted: 20-May-2019 Published: 27-May-2019 , DOI: 10.35248/2161-0487.19.9.359

Copyright: © 2019 Weise M. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.