Journal of Leukemia

Open Access

ISSN: 2329-6917

+44 1300 500008

ISSN: 2329-6917

+44 1300 500008

Case Report - (2021)Volume 9, Issue 9

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia occurring during the course of either sarcoidosis or tuberculosis is a rare phenomenon, but was already reported in the literature. The association of these three diseases is extremely rare and has never been reported before. Here we describe the case of a young woman with autoimmune hemolytic anemia, tuberculosis and sarcoidosis, and discuss the different diagnosis and management challenges.

Inflammation; Aging; Cytokines; Delirium; Dementia; Brain; Conditional logic; Boolean

Tuberculosis is an endemic infectious disease, affecting about 1% of the mondial population every year, mainly in developing countries. According to the World Health Organization, in 2018, tuberculosis was the first infectious cause of mortality in the world (1,2 to 1,45 million deaths). The disease affects mostly the lungs, but other localizations are also concerned (gut, lymph nodes, central nervous system). Primary splenic tuberculosis is an extremely rare entity, presenting less than 1.5% of intraabdominal forms [1]. Splenic localization is often part of systemic tuberculosis (80% of cases), mainly in HIV infected patients [2].

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease, in which lungs and the lymphatic system are the most affected [3].

Both tuberculosis and sarcoidosis are granulomatous diseases that display clinical and radiological similarities increasing the difficulty in establishing a differential diagnosis. Their association remain complex and sometimes undiagnosed [4].

Although rare, Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (AIHA) can be seen during tuberculosis [5]. The exact pathophysiology of hemolysis in this setting is yet to be elucidated. However, an altered immune response was implicated [6]. On the other hand, AIHA can occur during sarcoidosis also, but its mechanism remains unknown. The association of these 3 diseases is unusual and has never been reported before. It constitutes a real diagnosis and management challenge.

A 51 years-old woman, with history of type 2 diabetes mellitus under metformin and no transfusion history, consulted in the emergency room with recent onset of progressive dyspnea, low back pain and dark colored urine. There were no associated general symptoms (fever, night sweat, weight loss).

Physical examination showed generalized skin pallor with splenomegaly (8 cm under costal margin). The rest of the examination was unremarkable except from a left thyroid nodule with no associated goiter.

Laboratory workup showed normocytic regenerative anemia (Hemglobin: 5.4 g/dL; reticulocytes: 318 710/mm3), with agglutinated Red Blood Cells (RBC) at blood smear; lymphopenia (Ly: 0.3 × 109/L) and moderate thrombocytopenia (Platelets=131 × 109/L).

Hemolysis markers were positive (total bilirubin: 53 mg/L (normal range<17 mg/L) with free bilirubin predominance; Lactate dehydrogenase: 471 UI/L (normal range<225); haptoglobin was collapsed). Direct and Indirect Antiglobulin Tests (DAT, IAT) were positive for IgG and C3d complement antibodies, with a thermal optimum at 22°C and 37°C.

The rest of the laboratory workup was unremarkable (kidney, liver enzymes, thyroid functions, ferritin, folic acid, B12 vitamin, B, C and Human Immunodeficiency Virus serologies, as well as immunologic screening of antinuclear, anti-DNA antibodies and rheumatoid factor).

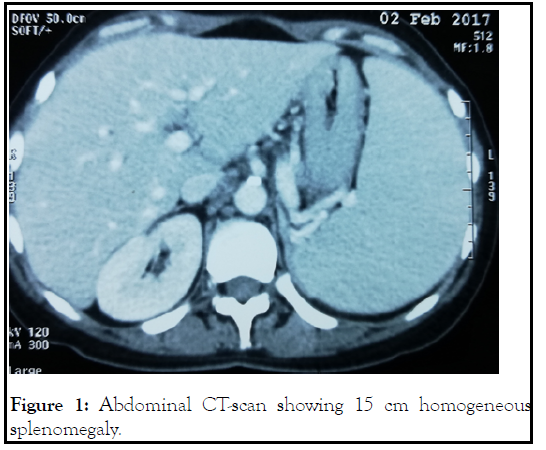

Computed tomography showed multiple supra and infradiaphragmatic lymphadenopathy with homogeneous splenomegaly and nodular goiter (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Abdominal CT-scan showing 15 cm homogeneous splenomegaly.

The patient underwent simultaneous thyroidectomy and mediastinal lymph node biopsy. Histological findings from the thyroid excision showed a heterogeneous multi-nodular goiter with no signs of malignancy. The lymph node biopsy revealed granulomatous lymphadenitis without caseous necrosis, consistent with the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Secondary testing for angiotensin conversion enzyme returened elevated. The patient started treatment with oral steroids (1 mg/kg/day of prednisone).

Initial evolution was good, with progressive increase in hemoglobin levels, but onset of cortico-dependance. Second line treatment with rituximab (2 doses: 1 g/dose given at 15 days interval) failed to give further improvement. Third line splenectomy was then decided in consultation with the patient.

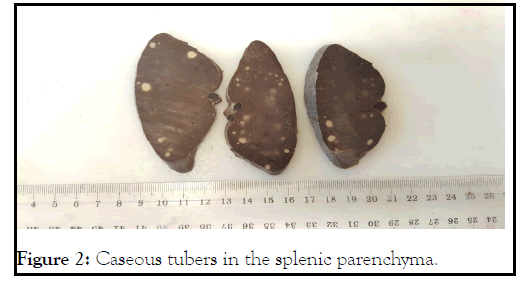

Macroscopic finding of the spleen showed homogeneous spleen with several whitish nodules (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Caseous tubers in the splenic parenchyma.

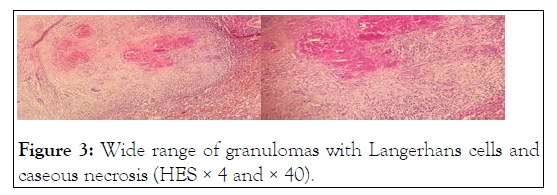

Histological examination showed epithelioid and giant cells granulomas with caseating necrosis, making the diagnosis of splenic tuberculosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3:Wide range of granulomas with Langerhans cells and caseous necrosis (HES × 4 and × 40).

Further tuberculosis workup (Polymerase Chain Reaction in the bone marrow and sputum, direct examination, tuberculosis culture and interferon-gamma release assays) were all negative.

Anti-tuberculous therapy according to local protocol was started (2 months of rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol, followed by 4 months of rifampicin and isoniazid), with slow corticosteroids tapering.

Anti-tuberculous therapy was well tolerated, but hemoglobin levels stayed stable around 10 g/dL with moderate biological hemolysis and positive DAT.

Few weeks after the end of anti-tuberculous therapy, the patient presented with progressive dyspnea and weight loss (15 kg). Hemoglobin levels dropped to 9,2 g/dl and hemolysis biomarkers increased.

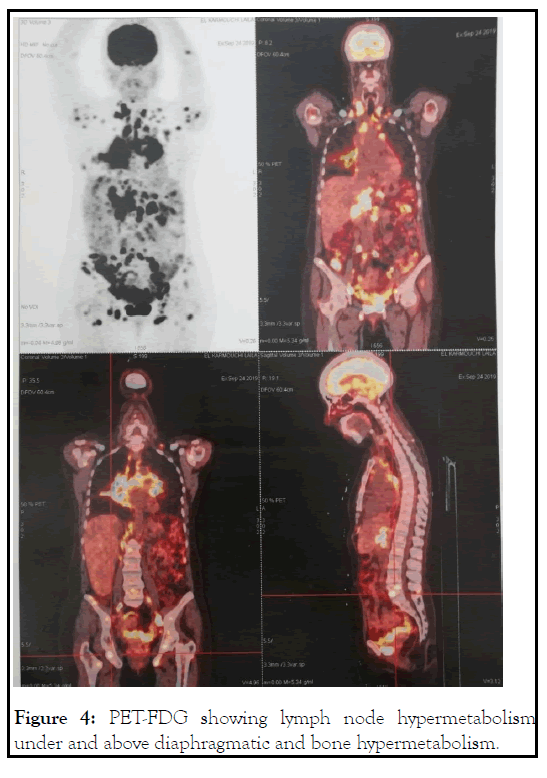

Chest tomography showed multiple mediastinal lymph nodes. Positron emission tomography with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (PETFDG) revealed intense hyper metabolism interesting supra- and infra-diaphragmatic lymph nodes, lungs, liver and bones (Figure 4).

Figure 4: PET-FDG showing lymph node hypermetabolism under and above diaphragmatic and bone hypermetabolism.

Cervical lymph node excision concluded to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis, with no signs of tuberculosis (histologically and by Polymerase Chain Reaction). Bone morrow biopsy was unremarkable.

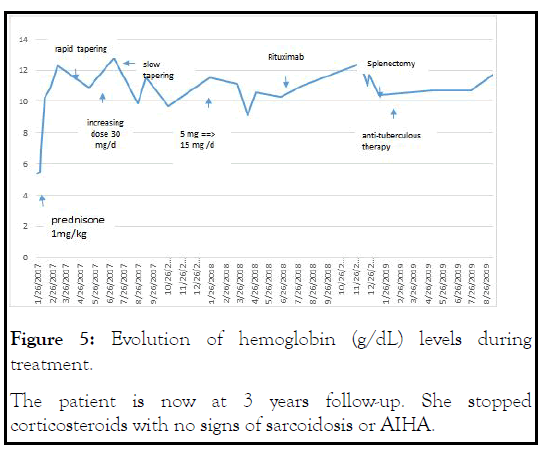

The patient restarted low-dose corticosteroids, with rapid improvement of dyspnea and normalization of hemoglobin levels as well as biological hemolysis (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Evolution of hemoglobin (g/dL) levels during treatment.The patient is now at 3 years follow-up. She stopped corticosteroids with no signs of sarcoidosis or AIHA.

Hematological abnormalities are usual during the course of tuberculosis [5]. Several mechanisms were implicated: nutrient deficiency, iron and other nutrients malabsorption, drugs allergy [6]. However, the association of AIHA is relatively rare. In animal models, the injection of Koch bacilli or their products induced hemolytic anemia, pancytopenia and myelofibrosis [7]. Indirect signs of hemolysis like pallor and hepatosplenomegaly are frequent during tuberculosis, usually improving under antituberculous therapy [8]. Auto-immune hemolytic anemia can also be a consequence of antituberculous therapy (ie. rifampicin). However, our patient presented AIHA before diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis.

To the best of our knowledge, 20 cases of AIHA and tuberculosis were reported (Table 1), the majority of them were disseminated and/or extrapulmonary forms. Only 1 case with splenic tuberculosis was reported [9].

| Autor/Year | Sex/Age | Site | Hemoglobin (g/dL) |

Antibody | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cameron et al. 1974 [6] | M/58 | Pulmonary | 4.4 | Cold | Anti-TB, RBC transfusion, corticosteroids |

| Semchyshyn et al. 1975 [19] | F/39 | Genito-urinary | 7.5 | Cold | Anti-TB, corticosteroids |

| Murray et al. 1978 [10] | M/49 | Pulmonary | 10.3 | Warm | Anti-TB |

| Siribaddana et al. 1997 [18] | M/37 | Nodal | 6.6 | Cold | Anti-TB |

| Blanche et al. 2000 [21] | M/42 | Disseminated | 3.7 | Mixed | Anti-TB, RBC transfusion, Corticosteroids, Splenectomy |

| Kuo et al. 2001 [11] | M/26 | Disseminated | 5 | Warm | Anti-TB |

| Abba et al. 2002 [17] | F/21 | Intestinal | 5.1 | Cold | Anti-TB, RBC transfusion |

| Turgut et al. 2002 [31] | F/30 | Pulmonary | 4.6 | N/A | Anti-TB |

| Bakhshi et al. 2004 [22] | F/8 | Disseminated | 1.8 | Mixed | Anti-TB, RBC transfusion, Corticosteroids |

| Gupta et al. 2005 [32] | M/8 | Intestinal | 8 | N/A | Anti-TB, Corticosteroids |

| Khemiri et al. 2008 [12] | F/11 | Pulmonary | 7.8 | Warm | Anti-TB |

| Chen et al. 2010 [13] | M/55 | Pulmonary | 3.8 | Warm | Anti-TB |

| Nandennavar et al 2011 [33] | F/19 | Nodal | 3.5 | N/A | Anti-TB |

| Wu et al. 2012 [16] | F/24 | Disseminated | 7.7 | Cold | Anti-TB, RBC transfusion |

| Kumar et al. 2013 [34] | M/23 | Pulmonary | 5.4 | N/A | Anti-TB |

| Safe et al. 2013 [14] | F/18 | Pulmonary | 8,3 | Warm | Anti-B, RBC transfusion |

| Somalwar et al. 2013 [35] | M/22 | Disseminated | 3.5 | N/A | Anti-B, RBC transfusion, Corticosteroids |

| Bahbahani et al. 2014 [15] | F/24 | Disseminated | 4.6 | Warm | Anti-B, RBC transfusion, Corticosteroids |

| Anurag et al. 2015 [20] | F/25 | Pulmonary | 4.5 | Cold | Anti-B, RBC transfusion |

| Kolla et al. 2016 [36] | F/32 | Pulmonary | 9.3 | N/A | Anti-B, Corticosteroids |

Table 1: Summary of reported cases of AIHA and tuberculosis.

Four patients with warm antibodies responded to antituberculous therapy without the need of further treatments (i.e. corticosteroids, transfusion...), and the lowest hemoglobin level described was 3,5 g/dL [10-13]. Red blood cells transfusion was rarely needed (only 2 patients before the start of antituberculous therapy) [14].Corticosteroids were used in only 1 case [15]. Moreover, in the 6 cases with cold antibodies, only 2 patients were treated with concomitant corticosteroids [6, 16-20]. Two patients with mixed antibodies also received corticosteroids [21,22]. One of them underwent splenectomy for splenic hematoma with hemolysis improvement [21]. The other one relapsed 2 months after initial treatment with corticosteroids and was rechallenged with the same treatment but with slow tapering [22].

Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic disease of unknown origin. The main lesions are immune granulomas of the affected organs, especially lungs and the lymphatic system [23]. Unlike tuberculosis, very few cases of sarcoidosis and AIHA have been reported. The causal relationship and mechanisms of such association are also misunderstood. The reported case was almost warm antibodies AIHA associated with sarcoidosis of different locations, generally well responding to corticosteroids [24-26].

Granulomatous inflammation in sarcoidosis is believed to be caused by some persistent poorly degradable antigen, and the resulting host response to it [27]. This antigenic stimulus can arise from noninfectious or infectious sources [28]. Various noninfective agents have been suspected primarily because of their epidemiologic association, but have not stood the test of time [29]. Similarly, a number of infective organisms have also been implicated in the pathophysiology of sarcoidosis [28]. Of these, tuberculosis is one of the strongest contenders till date [30]. The evidence for the role of mycobacterium tuberculosis in causality of sarcoidosis is multidimensional.

Our case raises several questions: 1) Initial presentation and laboratory workup does not support the diagnosis of tuberculosis. 2) The diagnosis of tuberculosis was done incidentally after splenectomy, used as a third line treatment for AIHA. 3) Unlike our expectations, anti-tuberculous therapy stabilized hemoglobin levels, but a complete response was not reached? This was probably caused by the concomitant flare of sarcoidosis. 4) This last fact was attested by PET-CT and biopsy findings, along with a good response to low dose corticosteroids (improvement of general symptoms and normalization of the hemolytic process) [31-36].

Splenic tuberculosis is a rare clinical presentation, even in tuberculous endemic regions like Morocco. Auto-immune hemolytic anemia may reveal tuberculosis in such settings. Diagnosis will be guided by clinical and radiological findings and confirmed by histology and/or microbiology. Concomitant inflammatory diseases such as sarcoidosis can be a confounding factor, making diagnosis and management more challenging. Clinicians should be aware of this associations, especially in bad responder to first line treatment.

None

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Citation: Aznag MA, Raissi A, Yahyaoui H, Chakour M, Haouane MA, Ameur MA (2021) Sarcoidosis, Tuberculosis and Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia: An Unusual Association!. J Leuk. 9(9): 271.

Received: 10-Sep-2021 Accepted: 24-Sep-2021 Published: 01-Oct-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2329-6917.21.9.271

Copyright: © 2021 Aznag MA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.