Journal of Hematology & Thromboembolic Diseases

Open Access

ISSN: 2329-8790

ISSN: 2329-8790

Original Research Article - (2022)Volume 10, Issue 7

Chronic Benign Neutropenia (CBN) and Autoimmune Neutropenia (AIN) are difficult to differentiate given their indistinguishable characteristics and challenges of anti-neutrophil antibody detection. We aim to investigate whether the presence of anti-neutrophil antibody affects the disease course of AIN and evaluate different methods in antineutrophil antibody detection. Chinese children with chronic neutropenia were recruited into the study between 2016 and 2018. A combination of in-house methods and a commercial kit were used for the detection of antibodies. Anti-neutrophil antibody was detected in 30.8% of patients and presence was associated with more severe neutropenia, higher likelihood of infection and slower and later recovery compared to those without antibodies. We conclude that the presence of anti-neutrophil antibody was useful in predicting the clinical course of patients with AIN. The use of combined testing methods increased the detection rate.

Immune cytopenia; Autoimmune Neutropenia (AIN); Chronic Benign Neutropenia (CBN); Antineutrophil antibody

AIN: Autoimmune Neutropenia; CBN: Chronic Benign Neutropenia; CIN: Chronic Idiopathic Neutropenia; GAT: Granulocyte Agglutination Test; GIFT: Granulocyte Immunofluorescence Test; G-CSF: Granulocyte Colony Stimulating Factor; HNA: Human Neutrophil Alloantigen; MAIGA: Monoclonal Antibody- Specific Immobilization of Granulocyte Antigens; NAIN: Neonatal Alloimmune Neutropenia

Chronic Benign Neutropenia (CBN) of infancy and childhood is characterized by a self-limiting low neutrophil count below 1.5 × 109/L lasting for at least six months [1]. The condition encompasses both Autoimmune Neutropenia (AIN) and Chronic Idiopathic Neutropenia (CIN). There continues to be a confusing overlap in the nomenclature and classification among the immune neutropenia syndromes despite sharing a similar benign clinical course, differing only in the presence or absence of anti-neutrophil antibodies [2]. The difficulty in differentiating the two lies with the variable accuracy and availability of the numerous testing modalities available for antibody detection [3] namely classical tests such as Granulocyte Agglutination Tests (GAT), Granulocyte Immunofluorescence Tests (GIFT), Monoclonal Antibody-Specific Immobilization of Granulocyte Antigens (MAIGA) and newer bead-based assay such as LABScreen multi (one lamda, Inc). The detection rate of antineutrophil antibodies in patients with CBN could be as high as 98%-100% when several testing methods are used [1,4]. According to an earlier cohort study by our group, Chinese children with AIN share similar clinical characteristics with patients of other western series, including the age of onset (9 months) and male to female ratio (4:6) [1,4,5]. Among the 24 children studied, they all experienced a relatively benign course regardless of their remission status [5]. Whether anti-neutrophil antibody testing plays a role in establishing a diagnosis, predicting outcome or have implications on follow up or management remains controversial, with various studies demonstrating conflicting evidence [1-8]. This prospective study aims to determine the prevalence of anti-neutrophil antibody among a larger group of Chinese children using multiple modalities of testing and whether the presence or absence of antibodies has implications on the clinical characteristics and prognosis of these patients.

This is a prospective cohort study conducted at a single center in the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong. Prior approval with the hospital Clinical Research Ethics and Institution Review Board was received HKU/HKWC IRB UW 15-379. Chinese children who were under 18 years old of age and found to have neutropenia, defined as Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC) ≤ 1.5 × 109/L lasting six months or more, were recruited into the study between 2016 and 2018. Information sheets are given and explained and informed consent was obtained. We excluded all patients with other causes of neutropenia for example: Congenital neutropenia, cyclic neutropenia, neutropenia ‘secondary’ to allo-immunity, or other immune or systemic diseases, because the etiologies, clinical manifestations, natural courses, and prognosis of these disease entities were different from those of CBN. Blood for anti-neutrophil antibody and genotyping was taken once at the time of recruitment and subsequently again when neutropenia recovered, which was defined as ANC ≥ 1.5 × 109/L for more than three months. These patients were followed up every three months with regular blood count monitoring for the duration they are neutropenic, anti-neutrophil antibody was repeated when the neutrophil count recovered. The cohort was followed up between the periods of April 2016 until April 2021. An initial screening with LABScreen multi (one lambda, Canoga Park, California, USA) was first performed and positive samples were then further tested by a combination of two in-house methods including GIFT, GAT for the detection of anti-neutrophil antibodies. GIFT detects antibodies anchored on the patient’s neutrophils using fluorescent labelled anti human IgG and can be detected by flow cytometry or by fluorescence microscopy. Whilst GAT involves incubating patient’s serum with neutrophils followed by microscopic evaluation for leucoagglutination. LABScreen multi is a multiplex commercial assay which allows for the simultaneous detection of Human Leucocyte Antigen (HLA) and Human Neutrophil Antigen (HNA) antibodies, where patient’s serum is mixed with microbeads coated with HNA and HLA antigens, bound antibodies were detected with R-Phycoerythrin (PE) conjugated anti-Human IGG. Florescence was detected with a luminex flow analyzer and evaluated with HLA FusionTM software (one lamda).

A total of 100 participants were identified during the study period of April 2016 until April 2021. One was excluded as he defaulted further blood taking after the initial recruitment and testing, 6 were excluded as non-ethnic Chinese and 12 excluded for other causes of neutropenia found later on. Secondary causes for exclusion included: Severe aplastic anaemia, severe congenital neutropenia, schwachman-diamond syndrome, xlinked chronic granulomatous disease, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. 81 participants with chronic benign neutropenia were qualified for the study. The age of onset, age of recovery, duration of neutropenia, gender, serial neutrophil counts, incidence of invasive infection, and use of Granulocyte-Colony Stimulator Factory (G-CSF) were examined. Invasive infection was defined arbitrarily as infection requiring hospitalization plus either surgical intervention or intravenous therapy.

The kaplan-meier method was used to estimate median overall recovery time for the neutropenia patients. Two-sided 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) for the median survival time were calculated by the brookmeyer-crowley method. COX regression analysis was used to determine the relationship of the antineutrophil antibody status with the recovery ratio, adjusting for the follow up time and their age of onset. Demographic information and results are presented as group medians, absolute counts and 95th interpercentile ranges or percentages. Stepwise multivariate logistic regression with the forward selection method was used to detect independent associations with the outcomes of interest, and p<0.05 was considered significant. Statistical comparisons were completed using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and JMP (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

The baseline characteristics of the 81 participants were similar in the gender distribution (Female=37 (45.7%), the median age of onset of neutropenia was 3.7 months (1.1-48)). The majority of patients presented with infection (n=39, 48.1%), predominantly viral infection (n=26, 66.7%), whilst invasive infection in the form of abscess made up 15.4%. No patients from this cohort developed bacteremia, invasive respiratory, central nervous system, urinary tract or bone infection at presentation. The second most common presentation was incidental finding from blood taking in neonates with prolonged neonatal jaundice (n=27, 33.3%), the rest made up by incidental finding during investigation for other conditions including failure to thrive, premature thelarche, congenital cataract and per rectal bleeding. Among these 27 infants picked up by neonatal jaundice screening, only 3/27 had detectable anti-neutrophil antibodies, 2/27 had persistent neutropenia during the period of follow up whilst the rest recovered, their median time to recover was 1.61 years which was shorter than the 2.65 years of the whole cohort. In the 81 participants with presumed CBN, anti-neutrophil antibodies were detected in 30.9% (n=25) of individuals. Antibodies against HNA-1a were detected in 21 individuals, whilst four were against HNA-3a. When comparing those with anti-neutrophil antibodies versus without (Table 1), AIN patients were significantly older in age of onset (median, 6.7 versus 2.1 months, p=0.0029), more likely to have severe neutropenia on presentation (neutrophil count<0.5 × 109/L, p=0.0437), more individuals with profound neutropenia (neutrophil count <1 ×109/L, p=0.0152) with the lowest neutrophil count also found to be lower (0.1 × 109/L versus 0.4 × 109/L, p=0.0005) and more likely to have invasive infection (n=6, 24% versus n=4, 7.1%, p=0.041). The majority of invasive infection occurred in the first year of diagnosis. Abscess was the most common presentation and involvement varied from skin, submandibular, perianal and in the finger. Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcal aureus was the most commonly cultured bacteria.

| Neutropenia characteristics | All patients (n=81) | Auto Ab positive (n=25) | Auto Ab negative (n=56) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of onset of neutropenia (months) | 3.7 (1.1-48.0) | 6.7 (1.1-27.2) | 2.1 (1.1-131.8) | 0.0029 |

| Age of recovery of neutropenia (years) | 3.0 (0.6-12.8) | 3.8 (0.6-5.3) | 2.91 (0.61- 17.2) | 0.1016 |

| Duration of neutropenia till recovery/last follow up within the follow up period (years) | 2.4 (0.6-12.3) | 2.7 (1.2-4.3) | 2.2 (0.6-1.7) | 0.2117 |

| Female gender | 37%, 45.7% | 12%, 48% | 25%, 44.6% | 0.78 |

| Severe neutropenia at presentation (<0.5 × 109/L) | 29%, 35.8% | 13%, 52% | 16%, 28.6% | 0.0443 |

| Moderate neutropenia at presentation (≥ 0.5 × 109/L and <1 × 109/L ) | 49%, 60.5% | 11%, 44% | 38%, 67.9% | 0.0437 |

| Mild neutropenia at presentation (≥ 1 × 109/L and <1.5 × 109/L ) | 3%, 3.7% | 1.40% | 2%, 3.6% | 0.9253 |

| Anaemia at presentation | 16%, 19.8% | 4.16% | 12%, 21.4% | 0.565 |

| Thrombocytopenia at presentation | 3%, 3.7% | 1.40% | 2%, 3.6% | 0.9253 |

| Lowest ANC value (× 109/L) | 0.3 (0.002-0.829) | 0.1 (0-0.8) | 0.4 (0-0.85) | 0.0005 |

| Invasive infection | 10%, 12.3% | 6%, 24% | 4%, 7.1% | 0.041 |

| G-CSF given | 5%, 6.2% | 3%, 12% | 2%, 3.6% | 0.1445 |

Data are medians (and 95% interpercentile range) or (and percentages).

Table 1: Comparison of clinical characteristics between anti-neutrophil antibody positive and negative individuals.

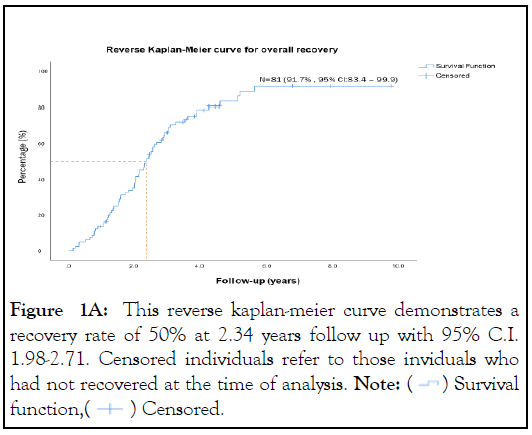

The time for 50% recovery probability for this cohort of neutropenia patients was 2.34 years from onset (95% C.I. 1.98 to 2.71) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1A: This reverse kaplan-meier curve demonstrates a

recovery rate of 50% at 2.34 years follow up with 95% C.I.

1.98-2.71. Censored individuals refer to those inviduals who

had not recovered at the time of analysis. Note:  Survival

function,

Survival

function,  Censored.

Censored.

Furthermore, anti-neutrophil antibody positive individuals were found to recover slower and later, based on the reverse Kaplan-Meier curve, it can be deduced that at 5 years follow up, 87.9% of anti-neutrophil antibody negative individuals recovered versus 69% of antineutrophil antibody positive individuals (p=0.035)(Figure 1B).

Figure 1B: The two reverse kaplan-meier curve of antineutrophil

antibody positive and negative patients are

compared and demonstrates that antibody positive patients

recovered slower and later compared to their antibody negative

counterparts. Note:  Negative,

Negative,  Positive.

Positive.

COX regression analysis found that the anti-neutrophil antibody status was independently associated with neutropenia recovery, where those with antibody-negative status had a 1.87 times higher chance of neutropenia recovery compared to antibodypositive individuals irrespective of follow-up time and age of onset.

Amongst the 81 samples processed, other than for 11 samples, the rest of the results were concordant amongst the three tests used. Among the discrepant samples, LABScreen multi detected anti-neutrophil antibodies in nine samples, which was not detected by GIFT and GAT. Whilst for two samples, LABScreen multi was negative and GIFT or GAT detected anti-neutrophil antibodies against HNA-3a antigen.

The true incidence of AIN amongst those diagnosed as CBN remains unknown as anti-neutrophil antibody testing is not routinely available amongst laboratories and cell-based antibody detection remains a technically demanding and time-consuming process. In the past, there has been conflicting opinions on the utility of antibody testing among CBN patients to specifically identify AIN individuals, given the overall benign and selflimiting clinical course of these individuals with only a small proportion of patients with significant infections [4-9]. Previously, some have commented that anti-neutrophil antibody detection did not correlate with the severity of neutropenia nor does it play any role in predicting prognosis in AIN [6,10], and therefore routine testing is not recommended [7,8]. In practice, anti-neutrophil antibodies are often difficult to detect as they often present in low titers and bind to their targets with poor avidity [10]. The detection rate varied amongst study groups ranging from 10%-98% [1-11], though all using different combination of testing methods. We report on a cohort of 81 Chinese children with presumed CBN, using the combination of cell-based and bead-based method, anti-neutrophil antibody was detected and therefore subclassified as AIN in 30.9% of the neutropenic cohort. Compared by an earlier study done by our group in 2004 reviewing the characteristics among Chinese children with CBN, using only cell-based method anti-neutrophil antibody was found in 21% of the group [5]. This demonstrates that using multiple methods of testing increases the detection rate of anti-neutrophil antibody, this was also recommended by previous studies [10,12]. Our overall detection rate for AIN is lower than recent studies that evaluated detection rate of LABScreen multi, which quoted up to 98% detection of HNA-1a, HNA-1b and HNA 2 antibodies, note that this study used preselected plasma donors previously identified to have antibodies with GIFT, GAT and MAIGA. In the same context, within our cohort, amongst 25 individuals identified to be antibody positive by GIFT/GAT, the LABScreen multi correctly identified 23/25 individuals, which demonstrates a similar specificity of 92%.

When comparing the two cell-based detection methods and bead-based methods, the combination of GIFT and GAT remains the gold standard in HNA antibody detection, however these tests are not suitable for high- throughput of samples [11]. It is known that GAT is very specific for detecting HNA antibodies, especially against HNA-3a due to their unique aggregation pattern. LABScreen multi, whilst easy to handle and suitable for high-throughput screening, remains costly and not ideal for detecting HNA-3a antibodies [13]. In this cohort, LABScreen multi detected antibodies where GIFT and GAT were negative in 13.6% (11/81) of the tested sample, whilst it was unable to detect 2.5% (2/81) of antibodies which were picked up subsequently by GAT and identified as against HNA-3a. These LABScreen multi Figures differed from those reported by Schulze, et al. [11] and Schonbacher et al. [13] who reported a false negative of 5.5% and 5.6% respectively and false positive result in 10% and 18% respectively. The contrasting numbers could be the result of those studies using donor sera pre-tested with GIFT/GAT, whilst in reality the antibody titers among patients with CBN could vary largely. Based on these findings, LABScreen multi should at least be applied in combination with the GAT to ensure reliable detection of anti HNA-3a and other more time-consuming methods such as GIFT, MAIGA should be implemented together to increase accuracy.

Previous groups including Madyastha, et al. [14] and Boxer, et al. [6] were not able to identify clinical characteristics that correlated with the presence of anti-neutrophil antibodies. Among our children, we were able to establish with statistical significance that the presence of antibodies was associated with older age of onset, more severe neutropenia on presentation, lower median neutrophil count and more likely to have invasive infection with abscess being the top cause. Furthermore, AIN individuals will recover slower and later compared to their antibody negative counterparts. This plays significant role in the counselling of parents of newly diagnosed with AIN on the clinical course and prognosis on their disease course, these children are often subject to regular blood taking and frequent hospital visits, with these findings, we are more confident in reassuring them and managing their expectations.

We also identified that amongst the initial presentations for neutropenia, the top reason being infection accounted for 48.1% (66.7%, 26/39 patients with self-limiting viral infections), this was followed closely by infants coming in for investigation for prolonged jaundice exceeding the first two weeks of life (33.3%). In our hospital’s neonatology unit, neonates screened to have jaundice beyond first two weeks of life in the community are called back for blood screening to rule out conditions that could predispose individuals to prolonged jaundice, the complete blood profile is often ordered along with the liver function. Among these 27 infants, further investigations for the child and parents for maternal alloantibodies in the setting of neither Neonatal Alloimmune Neutropenia (NAIN), nor HNA genotyping were done, and could therefore not be excluded in this cohort. Given that these infants were not reported to experience invasive infection during the study period, and the overall low incidence of NAIN which often are asymptomatic further extensive work up was not done [15]. The antineutrophil antibody detection rate was only 0.1% amongst these infants, which was lower that the literature reported 0.35%-1.1%. Another postulated explanation could be that since these infants are mostly breastfed, antibodies could deliver through their mother’s breast milk and therefore the pathophysiology may slightly differ then those of classical CBN, AIN or NAIN. The inclusion of this group of children may contribute to overall lower age of onset of neutropenia within this cohort compared to the usual 5-15 months [1,4] and may also contribute to the lower antibody detection rate. If excluded, our overall antibody detection rate would increase to 40.7% (22/54). Given the opportunity, it may be useful to look into similar aged infants and testing their parents to determine whether they’re truly cases of NAIN and comparing their clinical course with those with classical CBN and AIN. We have included a suggested diagnostic pathway for children with isolated neutropenia for guidance (Figure 1C).

Figure 1C: Proposed approach to childhood neutropenia.

In summary, following this cohort of Chinese children, we can conclude that the presence of anti-neutrophil antibodies in AIN has implications on the severity of neutropenia, infective complications and also prognosis. This serves as an important tool for clinicians to counsel parents and guides clinician’s follow up approach in patients with AIN. What’s more, we have demonstrated that the combined use of cell-based and beadbased detection methods increases the detection rate. Whilst the classical cell-based methods are labor intensive and arduous, it should be implemented together with bead-based methods to increase its diagnostic accuracy.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Anandhi A, Mufti HN, Quispe A, Iwamoto T. (2022) Significance of Anti-Neutrophil Antibody in Chronic Benign Neutropenia in Chinese Children. J Hematol Thrombo Dis. 10:506

Received: 08-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. JHTD-22-19968; Editor assigned: 11-Nov-2022, Pre QC No. JHTD-22-19968 (PQ); Reviewed: 25-Nov-2022, QC No. JHTD-22-19968; Revised: 02-Dec-2022, Manuscript No. JHTD-22-19968 (R); Published: 09-Dec-2022 , DOI: 10.35248/2329-8790.22.10.506

Copyright: © 2022 Anandhi A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.