Clinical Pediatrics: Open Access

Open Access

ISSN: 2572-0775

ISSN: 2572-0775

Research Article - (2023)Volume 8, Issue 3

Background: Globally in U5 year children, greater than half of all deaths are attributable to under-nutrition. Stunting is one of the major under-nutrition problems in children, especially in developing countries like Ethiopia. Therefore, this study was aimed to assess the prevalence of stunting and its associated factors among children age 6-59 months at Debre Tabor town, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019.

Materials and methods: Community-based cross-sectional study design was conducted among children age 6-59 months at Debre Tabor town, from February to March 2019. Data were collected using a pretested, semi-structured an interviewer-administered questionnaire adapted from World Health Organization Stepwise Surveillance (WHO STEPS). A systematic random sampling technique was used to engage 620 parent-child pairs. Data was entered into Epi-info version 7 and exported to SPSS version 22 for analysis. Height for age Z score was computed using WHO Anthro plus software. Both the bi-variable and a multivariable logistic regression analyses were computed and Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) at p-value <0.05 was used to determine the statistically significant association between factors and the outcome variable.

Results: The prevalence of stunting in this study was 46% (95% CI: 41.9%-50.3%). Age of the child (AOR=1.98, 95%CI: (1.08, 3.67)), occupation of the mother (AOR=2.13, 95% CI: (1.16, 3.92)), educational status of the father (AOR=2.88, 95% CI: (1.45, 5.70)) and occupation of the father (AOR=5.05, 95% CI: (2.46, 10.36)) were variables significantly associated with stunting.

Conclusion: The prevalence of stunting was found to be high among children age 6-59 months in the study area as compared to the national average. The age of the child, occupation of the mother, the educational status of the father, and occupation of the father were factors associated with stunting? Therefore, attention should be targeted to improve the occupational and educational status of the parents.

Children; Stunting; Debre tabor town; Ethiopia

World Health Organization (WHO); United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF); Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS); WHO Stepwise Surveillance (WHO STEPS); Principal Component Analysis (PCA); Standard Deviation (SD); Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR); Confidence Interval (CI)

Globally, in fewer than five children greater than half of all deaths are attributable to under-nutrition [1]. Besides, stunting is one of the most common markers of under-nutrition, which is a linear growth failure or inability to gain a potential height for a particular age [2,3].

According to United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and World Bank 2019 reports, more than one in five children under the age of 5 years had stunted growth. Even though stunting decreases globally from in the last decades, it is increased in alarming rates in Africa [4]. Furthermore, in Ethiopia, according to the Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS) 2016, stunting was 38% [5].

According to WHO conceptual frame work on childhood stunting, the household and family incomes, breastfeeding techniques of children, infection, and complementary feeding practices were some of the contributing factors of stunting [6]. The global review of stunting in low and middle-income countries also identified that growth restriction in-utero and lack of access to sanitation as the main driving factors for stunting [7]. Consequently, stunting in children results in susceptibility to infectious disease, diminish intellectual ability, and poor school performance [8-10]. Moreover, stunted children may never regain their height loss again in their lifetime [11].

Despite the global burden of stunting, it is not often recognize in the communities, especially in low and middle-income countries like Ethiopia [12,13]. Even though, stunting in Ethiopia, reduced from 58% according to Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS) 2000 to 38% EDHS 2016, in under-five children. However, this progress is not sufficient to meet the global target [14,15]. The risk factor of stunting in a different setting is different for under-five children [16]. Thus, to address this gap, this study was aimed to assess the prevalence of stunting and its associated factors among children age 6-59 months at Debre Tabor town, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019.

Study design and setting

Community-based cross-sectional study design was conducted to assess stunting among children age 6-59 months at Debre Tabor town, Northwest Ethiopia, from February to March 2019. The study was conducted at Debre Tabor town, which is found in the Northwest part of Ethiopia. The general population of Debre Tabor town is estimated to be 84,382 of this 10,868 were children, age 6-59 months [17].

Study participants and sampling

All children age 6-59 months living at Debre Tabor town were eligible for this study. The town has six kebeles; each kebele was considered as a cluster. Then, three clusters (50% of the cluster) were selected randomly by the lottery method. Households with children age 6-59 months in the three clusters were obtained from health extension workers in each cluster. Using health extension workers registrations as a frame of reference studied households were selected by systematic random sampling technique. For more than one eligible child in one household, the lottery method was used.

Dependent variable

Stunting (below -2 SD) children age from 6-59 months. A child is defined as stunted if the height-for-age Z-score is found to be below -2 SD of the median of the WHO standard curve.

Independent variables

• Socio- demographic and economic characteristics.

• Maternal characteristics.

• Childs’ characteristics.

• Environmental characteristics.

Data collection tools and procedures

Data were collected by using a pretested, semi-structured interviewer-administered questionnaire, which is adopted from WHO Stepwise Surveillance (WHO STEPS) for child malnutrition. The questionnaire comprised of socio-demographic, economic, environmental conditions, and child health-related characteristics.

The data were collected by five BSc nurses. Mothers or caregivers were interviewed whereas; anthropometry measurements were taken from children. The height of infants aged six to 23 months was measured in a recumbent position to the nearest 0.1 cm, using a board with an upright wooden base and movable headpieces. Children aged 24 to 59 months were measured in a standing up position to the nearest 0.1 cm. Additionally, child weight was measured by an electronic digital weight scale to the nearest 0.1 kg. The calibers of the measurements were checked before and after the measurement of the individual child.

Data processing and analysis

Data were entered into EPI-info version 7 and then exported to SPSS version 12 for analysis. WHO Anthro-Plus software was used to convert nutritional data into Z scores of the indices HAZ using the WHO standard. In addition, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to compute family wealth status.

Both bivariate and multivariable binary logistic regression models were computed to identify factors associated with stunting among children age 6-59 months. A bivariate binary logistic regression model was first computed, and variables less than 0.2 in the bivariate analysis were entered into the multivariable logistic regression model. In the final multivariable analysis, variables having a p-value less than 0.05 at 95% CI were considered as significantly associated with stunting.

Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of the study participants

A total of 620 children age 6-59 months were included in the analysis. The majority (91.0%) of the mothers/caregivers were married and (90.6%) Orthodox Christian in Religion. Nearly three fourth (72.4%) of the fathers had high school and above educational status (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | Married | 564 | 91 |

| Single | 56 | 9 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 562 | 90.6 |

| Muslim | 44 | 7.1 | |

| Protestant | 14 | 2.3 | |

| Ethnicity | Amhara | 601 | 96.9 |

| Oromo | 17 | 2.7 | |

| Gurage | 2 | 0.3 | |

| The educational status of the mother | No formal education | 127 | 20.5 |

| Primary education | 143 | 23.1 | |

| High school and above | 350 | 56.5 | |

| The educational status of the father | No formal education | 97 | 15.6 |

| Primary education | 74 | 11.9 | |

| High school and above | 449 | 72.4 | |

| Occupation of mother | Housewife | 284 | 46.5 |

| Daily laborer | 41 | 6.7 | |

| Private organization | 21 | 3.4 | |

| Merchant | 95 | 15.5 | |

| Government employee | 170 | 27.8 | |

| Occupation of father | Daily laborer | 95 | 15.5 |

| Private organization | 96 | 15.7 | |

| Merchant | 158 | 25.8 | |

| Government employee | 264 | 43.1 | |

| Family size | Less than 5 | 503 | 81.1 |

| Greater than or equal to 5 | 117 | 18.9 | |

| Total number of under-five children | ≤ 2 | 466 | 75.2 |

| >2 | 154 | 24.8 | |

| Total number of children | Less than four | 576 | 92.9 |

| Greater than or equal to four | 44 | 7.1 | |

| Wealth status of the family | Poor | 204 | 32.9 |

| Medium | 208 | 33.5 | |

| Rich | 208 | 33.5 | |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of children age 6-59 months at Debre Tabor town, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019 (n=620).

Child characteristics

The mean age of the study participants was 27 (± 14 SD) months. Slightly higher than half (52.3%) of the children were males. Six hundred twelve (98.7%) of children were ever immunized (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex of the child | Male | 324 | 52.3 |

| Female | 296 | 47.7 | |

| Age of the child 27 ± 14 SD |

6-11 months | 110 | 17.7 |

| 12-23 months | 146 | 23.5 | |

| 24-35 months | 159 | 25.6 | |

| 36- 47 months | 138 | 22.3 | |

| 48-59 months | 67 | 10.8 | |

| Ever breastfeeding | Yes | 615 | 99 |

| No | 5 | 1.1 | |

| Ever immunized | Yes | 612 | 98.7 |

| No | 8 | 1.3 | |

| Breastfeeding initiations time | Before 1 hour | 500 | 81 |

| Greater than 1 hours | 120 | 19 | |

| Pre-lacteal feeding use | Yes | 47 | 7.6 |

| No | 573 | 92.4 | |

| Types of pre-lacteal feeding | Water | 16 | 2.6 |

| Butter | 14 | 2.3 | |

| Milk | 15 | 2.4 | |

| Others (Habish, meqamesha) | 2 | 0.3 | |

Note: SD: Standard Deviation.

Table 2: Child characteristics of children age 6-59 months at Debre Tabor town, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019 (n=620).

Maternal characteristics

Five hundred ninety-one (95.3%) of the mothers/caregivers utilize family planning methods. Nearly three fourth (72.6%) of the mothers were utilized Depo-Provera (Table 3).

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of the mothers/caregivers | <25 | 69 | 11.1 |

| 25-30 | 303 | 48.9 | |

| >30 | 248 | 40 | |

| Family planning utilizations | Yes | 591 | 95.3 |

| No | 29 | 4.7 | |

| Pills | Yes | 119 | 19.2 |

| No | 501 | 80.8 | |

| Depo-Provera | Yes | 450 | 72.6 |

| No | 170 | 27.4 | |

| Norplant | Yes | 104 | 16.8 |

| No | 516 | 83.2 | |

| Is the pregnancy planned | Yes | 548 | 88.4 |

| No | 72 | 11.6 | |

Table 3: Maternal characteristics of children age 6-59 months at Debre Tabor town, Northwest Ethiopia 2019 (n=620).

Environmental characteristics

Five hundred and fifty-six (89.7%) of the respondents use private tap water as their main water source. The majority of the respondents 615 (99.2%) have latrine. Eighty-five (13.7%) of the respondents don't have a separate kitchen for their food preparations (Table 4).

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source of drinking water | |||

| Private well | Yes | 129 | 20.8 |

| No | 491 | 79.2 | |

| Private tap | Yes | 556 | 89.7 |

| No | 64 | 10.3 | |

| Public tap | Yes | 26 | 4.2 |

| No | 594 | 95.8 | |

| Spring water | Yes | 92 | 14.8 |

| No | 528 | 85.2 | |

| Amount of water used in the household | <50 liters | 332 | 53.5 |

| 50-75 liters | 282 | 45.5 | |

| >75litrs | 6 | 1 | |

| Water treatment utilizations | Yes | 98 | 15.8 |

| No | 522 | 84.2 | |

| Latrine | Yes | 615 | 99.2 |

| No | 5 | 0.8 | |

| Type of latrine | Private pit/wooden slab | 503 | 81.2 |

| Private slab/cement Slab | 77 | 12.5 | |

| Shared latrine/wooden Slab | 7 | 1.2 | |

| Shared VIP latrine | 13 | 2.1 | |

| Others like an open field | 20 | 3 | |

| Waste disposal | Open field | 190 | 30.6 |

| Private pit | 49 | 7.9 | |

| Common pit | 21 | 3.4 | |

| Composting | 10 | 1.6 | |

| Burning | 302 | 48.7 | |

| Other | 48 | 7.7 | |

| Kitchen | Yes | 535 | 86.3 |

| No | 85 | 13.7 | |

Table 4: Environmental characteristics of children age 6-59 months at Debre Tabor town, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019 (n=620).

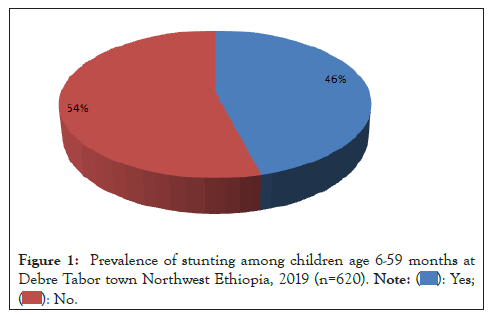

Prevalence of stunting among children age 6-59 months

The overall prevalence of stunting among children age 6-59 months at Debre Tabor town was 46% at 95% CI (41.9-50.3) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Prevalence of stunting among children age 6-59 months at

Debre Tabor town Northwest Ethiopia, 2019 (n=620).

Factors associated with stunting among children age 6-59 months

In the bivariate logistic regression analysis, age of the child, educational level of the mother, educational level of the father, occupation of the father, occupation of the mother, total number of children, family size, family planning use, and family wealthy status were significantly associated with stunting. However, in the multivariable logistic regression analysis; the age of the child, the educational status of the father, occupation of the father, and occupation of the mother remained significantly associated with stunting.

The odds of having stunting among children with the age group of 12-23 months were nearly 2 times higher as compared to children with age groups of 6-11 months age (AOR=1.98; 95%CI: 1.08,3.67). The odds of having stunting among children who had a daily laborer fathers were 5 (AOR=5.03; 95%CI: 2.45,10.36) times and children with father who works in private organizations were 2.4 (AOR=2.36; 95%CI: 1.29, 4.33) times higher as compared with children whose fathers were governmental employees respectively. Similarly, the odds of having stunting among children who had a father with no formal education were nearly 3(AOR=2.88; 95%CI: 1.45, 5.70) times and children with fathers who attend primary school were 2 (AOR=1.98; 95%CI: 1.03, 3.79) times higher as compared to children with fathers who attended high school and above educational level respectively. The odds of having stunting among children who had housewife mothers were 2 times higher than children of their mothers who were a governmental employee (AOR=2.13; 95%CI: 1.16, 3.92) (Table 5).

| Variable | Stunted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | COR at 95% CI | AOR at 95% CI | ||

| Age | 6-11months | 35 | 75 | 1 | 1 |

| 12-23 months | 70 | 76 | 1.97(1.18,3.31) | 1.98(1.08,3.67)* | |

| 24-35 months | 73 | 86 | 1.81(1.09,3.02) | 1.54(0.84,2.82) | |

| 35-47 months | 69 | 69 | 2.14(1.27,3.61) | 1.45(0.78,2.71) | |

| 48-59 months | 38 | 29 | 2.81(1.49,5.26) | 1.45(0.68,3.10) | |

| Maternal education | No formal education | 85 | 42 | 4.25(2.76,6.54) | 0.89(0.46,1.73) |

| Primary education | 87 | 56 | 3.26(2.18,4.88) | 1.22(0.73,2.06) | |

| High school and above | 113 | 237 | 1 | 1 | |

| Educational status of the father | No formal education | 71 | 26 | 4.84(2.97,7.89) | 2.88(1.45,5.70)** |

| Primary education | 52 | 22 | 4.19(2.45,7.15) | 1.98(1.03,3.79)* | |

| High school and above | 162 | 287 | 1 | 1 | |

| Occupation of the mothers | Housewife | 169 | 115 | 5.88(3.77,9.17) | 2.13(1.16,3.92)* |

| Daily laborer | 28 | 13 | 8.62(4.04,18.38) | 1.47(0.57,3.81) | |

| Private organizations | 6 | 15 | 1.60(0.58,4.43) | 0.65(0.19,2.10) | |

| Merchant | 43 | 52 | 3.31(1.91,5.74) | 1.3(0.68,2.67) | |

| Gov’t employee | 34 | 136 | 1 | 1 | |

| Father occupation | Daily laborer | 76 | 19 | 13.03(7.31,23.2) | 5.05(2.46,10.36)* |

| Private organization | 56 | 40 | 4.56(2.78,7.49) | 2.36(1.29,4.33)** | |

| Merchant | 86 | 72 | 3.89(2.55,5.94) | 1.71(0.99,2.96) | |

| Gov’t employee | 62 | 202 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total number of family | Less than 5 | 214 | 289 | 1 | 1 |

| Greater than or equal to 5 | 71 | 46 | 2.08(1.38,3.14) | 0.57(0.32,1.01) | |

| Total number of children | Less than four | 258 | 318 | 1 | 1 |

| Greater than or equal to four | 27 | 17 | 1.96(1.04,3.67) | 0.65(0.27,1.58) | |

| Total number of under-five children | ≤ 2 | 206 | 260 | 1 | 1 |

| >2 | 79 | 75 | 0.75(0.52,1.04) | 1.13(0.72,1.78) | |

| Current family planning use | Yes | 202 | 268 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 83 | 67 | 1.64(1.34,2.4) | 1.52(0.95,2.42) | |

| Family wealth | Poor | 125 | 79 | 3.05(2.04,4.56) | 1.38(0.84,2.26) |

| Medium | 89 | 119 | 1.44(0.97,2.15) | 1.11(0.70,1.77) | |

| Rich | 71 | 137 | 1 | 1 | |

Note: 1: Reference; *: (p<0.05) significant; **: (p<0.001) highly significant; COR: Crude Odds Ratio; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval.

Table 5: Factors associated with stunting among children age 6-59 months at Debre Tabor town Northwest, Ethiopia, 2019 (n=620).

Stunting is a major public health problem globally. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of stunting and its associated factors among children age 6-59 months in Debre Tabor town, Northwest Ethiopia.

The overall prevalence of stunting in this study was 46% (95%CI; 41.9, 50.3), which is in line with a cross-sectional study conducted in Labella town, Ethiopia 47.3%, Wukro town, Tigray region, Ethiopia 49.2%, Arba Minch Health and Demographic Surveillance Site (HDSS), Ethiopia 47.9%, Pastoral Communities of Afar Regional State, Ethiopia 43.1%, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia 46.3% and Bule Hora, Ethiopia 47.6% [18-23].

However, the finding in this study is higher than the national average reported by EDHS 2016 38% and other studies conducted at West Gojjam, Ethiopia 24.9%, Aykel town, Northwest Ethiopia 28.4%, SodoZuria District, South Ethiopia 24.9%, Evidence from 2016 Demographic and Health Survey, Ethiopia 38.3%, Bishoftu Town, Oromia Region, Ethiopia 16.1%, Damot Gale district, Southern Ethiopia 41.7% [24-29].

This might be due to dietary diversity differences in different areas of Ethiopia. Ethiopia is a multicultural country, which had different child feeding cultures [30,31].

The result in our study is also higher than study conducted in Zambia 40%, Nigeria 38.7%, Southwestern Nigeria 18.6%, Thailand 28.8%, and china 8.4% [32-35]. This might be directly related to the difference in the economic status of the countries.

The underline cause of stunting in children is poverty and lack of educations. Therefore, children lived-in low-income countries like Ethiopia lead to the inadequacy of foods, there is also a problem with the preparations of clean and diversified foods, which directly may cause stunting [36].

On the other hand, the prevalence of stunting in this study was lower than the study done in Belesa, Ethiopia 57.7% and Kayin State, Myanmar 59.4% [37]. The higher result observed in Belesa might be due to the fact that the Belesa district is mostly affected by drought, and the study was conducted among rural households [38,39].

The odds of having stunting among children with the age group of 12-23 months were nearly 2 times higher as compared to children with age groups of 6-11 months age (AOR=1.98; 95%CI: 1.08, 3.67), which is supported by a study conducted in Labella Town, Ethiopia, Damot Gale district, southern Ethiopia 41.7%, SodoZuria District, South Ethiopia 24.9% and Zambia.

This is due to the fact that, in most studies, breastfeeding is universal in Ethiopia, and mostly it continues up to 1 year of age. As we all now breastfeeding greatly reduces the occurrence of stunting. Therefore, after one year of age when most children cease breastfeeding, they might be exposed to stunting.

The other possible explanation might be, in most cases, children are exposed to family food at the age of one to two years. This might again expose the child to stunting. Researchers suggested that children accumulate growth delay during the first 2 years of life with stunting peaking around 2 and 3 years after which they stabilize [40].

The odds of having stunting among children who had a daily labourer father were 5 (AOR=5.03; 95%CI: 2.45, 10.36) times and children with a father who works in private organizations were 2.4 (AOR=2.36; 95%CI: 1.29, 4.33) times higher as compared with children whose fathers were governmental employees respectively. This might be related to the family income and feeding status of the children, children with government employee fathers would have better income as compared to their counterparts.

The odds of having stunting among children who had a father with no formal education were nearly 3 (AOR=2.88; 95%CI: (1.45-5.70)) times and children with fathers who attend primary school were 2 (AOR=1.98; 95%CI: (1.03-3.79)) times higher as compared to children with fathers who attended high school and above educational level respectively.

This is supported by a study conducted at West Gojjam, Ethiopia 24.9%. The possible reason might be educated fathers had better awareness regarding the kinds and amounts of food appropriate for their children. As the level of education increase, the knowledge of fathers towards child feeding practices, common childhood disorders, child nutritional problems will increase, therefore, stunting will be decreased.

The odds of having stunting among children who had housewife mothers were 2 times higher than children of their mothers who were a governmental employee (AOR=2.13; 95%CI: 1.16, 3.92). This might be due to related to the income and educational level of the mothers. If the mothers were employed, they should have formal education which implies they will have better awareness regarding child feeding practice. On the other hand, if the mothers were employed, they will have a good income as compared to housewife mothers.

The prevalence of stunting was found to be higher among children age 6-59 months in Debre Tabor town as compared to the national average. The age of the child, the educational status of the father, occupation of the father, and occupation of the mother were variables significantly associated with stunting in this study. Therefore, attention should be targeted to improve the occupational status and the educational levels of the parents.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the school of the nursing ethical review committee on behalf of the University of Gondar review board. The verbal informed consent was acceptable and approved by Ethical review board on the behalf of University of Gondar. A permission letter was obtained from the Debre Tabor town department of health. Participants were informed about voluntarism and that they can withdraw at any time of the study if they want not respond. For those who were a volunteer to participate, verbal informed consent was obtained from the mother/caregivers/for the children involved in this study. At the end of the interview, participants were informed about stunting and associated potential effects

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank the University of Gondar for financial support that made this study possible. They would also like to thank the data collectors for their tolerance and collaboration during the work.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Getu BD, Atalell KA, Kassie DG, Azanaw KA, Tibebu NS (2023) Stunting and its Associated Factors among Children Age 6-59 Months at Debre Tabor Town, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019: A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study. Clin Pediatr. 8:238.

Received: 24-Apr-2023, Manuscript No. CPOA-23-21391; Editor assigned: 26-Apr-2023, Pre QC No. CPOA-23-21391 (PQ); Reviewed: 10-May-2023, QC No. CPOA-23-21391; Revised: 17-May-2023, Manuscript No. CPOA-23-21391 (R); Published: 26-May-2023 , DOI: 10.35248/2572-0775.23.8.238

Copyright: © 2023 Getu BD, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.