Anesthesia & Clinical Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-6148

ISSN: 2155-6148

Research Article - (2022)Volume 13, Issue 8

Study design: Retrospective study.

Objective: To describe the pattern and the surgical management of patients with traumatic spine injury in Lomé, Togo.

Patients and methods: We conducted a retrospective and descriptive from November 2017 to October 2020. We included adult patients who presented with traumatic spine injury and who underwent surgery stabilization.

Results: A total of 93 patients were studied. The population was young (35.92 ± 9.68 years old), men (91.4%). Road traffic accidents accounted for 85% of patients. At presentation, 59.1% of patients had an incomplete neurologic deficit (ASIA B-D). The cervical spine was the most common segment injured (57%). The median time from admission to the operating room was 21.06 ± 11.8 days. After surgery, 15.3% improved by at least 1 ASIA grade. Bedsores (14%) and superficial wound infection (10.8%) were the most typical complications in our series after surgery.

Conclusion: Traumatic spinal injury in Lomé mainly occurred in young adult males. It is affecting mainly the cervical spine. Despite limitations in medical resources, spine surgery appears promising in our country.

Spine trauma; Spinal fractures; Global neurosurgery; Patients

A Traumatic Spinal Injury (TSI) is a global disease burden in Low and Middle–-Income Countries (LMIC). The burden of TSI is higher in LMICs than in developed countries [1]. After acute TSI, the annual case mortality rate is nearly 20% in Thessaloniki and 0% in Stockholm [2]. In sub-Saharan Africa, acute mortality rates from TSI range from 18% to 25% [3,4]. Despite improvements in TSI management, resource-constrained settings have not benefitted from this progress to the same extent as more developed countries [5,6]. For example, neurosurgery remains tertiary and expensive in Togo.Neurosurgery has been developed in Togo since 2008.However, stabilization techniques and time to surgery for TSI are not reported in Togo. This study describes the operative management of patients undergoing surgical stabilization for TSI at Sylvanus Olympio Teaching Hospital.

We conducted a retrospective and descriptive study at the neurosurgery unit of Sylvanus Olympio teaching hospital in a developing country (Togo) between September 2017 and October 2020. Togo is a West African francophone low-income country. The population was 8.082. 366 inhabitants in 2019. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is USD 5.49 billion in 2019. According to the World Bank, Life expectancy was 61.042 years old in 2019 [7]. After approval of the hospital's ethics committee, we included in the study adult patients who underwent surgical intervention for TSIs. We excluded patients who underwent decompression only (laminectomy without instrumentation or fusion), were <15 years old, had a concomitant brain injury. We collected socio-demographic data, including age, gender, and mechanism of injury. Insurance status was classified as private or public.

For classification of fractures, neurologic status, surgery, and timing, we proceed as Magogo et al. in Tanzania [8].

Subaxial and thoracolumbar fractures were classified according to AO classification [9].

To decipher trends in management, fractures of similar patterns were grouped by mechanism and amount of listhesis/ translation. Listhesis was defined as: I=25%, II=50%, III=75%, IV=100%.

The American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale was used for neurologic exams at admission and at discharge [10]. Surgery was indicated and done for unstable fracture (AO type A4, B, or C) and potentially unstable fracture (AO type A1-A3, with neurologic impairment: ASIA A-D). Patients with public insurance or without insurance must pay for their own implants. If a family had a resource limitation, it could pay only for four screws. The surgeon was so forced to treat the injury with these screws. We performed Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion with plate (ACDF), Anterior Cervical Corpectomy with tricortical iliac crest graft and plate (ACC), Poster lateral thoracic or Lumbar Laminectomy, and Fusion with pedicle screws (PLF). Statistical analysis and data processing was performed with the software SPSS version 25. We used nonparametric tests to assess predictors of timing, multivariate logistic regression to assess predictors of improvement in neurologic status. Variables with a value of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

During the period, 93 patients were admitted for TSI. There were 85 men (91.4%) and eight women (8.6%). The mean age of the series was 35.92 ± 9.68 years old (range 18–64). In our conditions of practice, 75 (80.6%) patients did not have any insurance, 2 (2.2%) had private insurance, and 16 (17.2%) had public insurance.

Mechanisms, level of injury, neurologic status, and operative information are summarized in Table 1.

| Mechanism, n (%) | |

|---|---|

| motorcycle accident | 65 (69.9) |

| Fall | 9 (9.7) |

| motor vehicle accident | 14 (15.1) |

| blunt object | 1 (1.1) |

| Pedestrian | 4 (4.3) |

| Location, n (%) | |

| cervical spine | 53 (57) |

| cervicothoracic spine | 4 (4.3) |

| thoracic spine | 12 (13) |

| thoracolumbar spine | 4 (4.3) |

| lumbar | 19 (20.5) |

| Neurologic status, n (%) | |

| complete (ASIA A) | 29 (31.2) |

| incomplete (ASIA B-D) | 55 (59.1) |

| intact (ASIA E) | 9 (9.7) |

| Surgery, n (%) | |

| ACDF | 40 (43) |

| ACDF+corporectomy | 7 (7.5) |

| ACDF+laminectomy | 10 (10.8) |

| PLF | 7 (7.5) |

| PLF+Laminectomy | 29 (31.2) |

Note: ACDF: Anterior Cervical and Fusion with Plate; PLF: Postero Lateral Fusion.

Table 1: Injury, admission ASIA score and operative information.

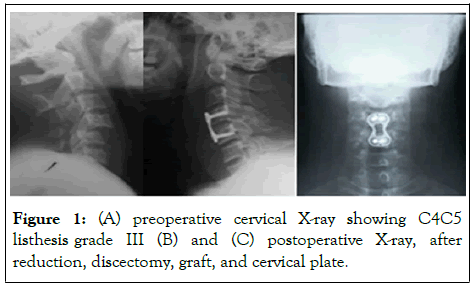

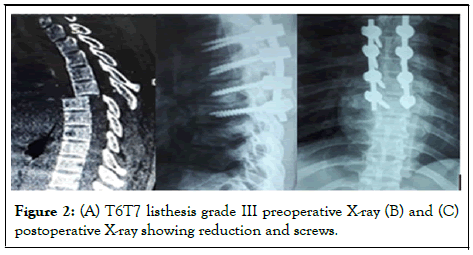

All patients underwent surgical stabilization procedures (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: (A) preoperative cervical X-ray showing C4C5 listhesis grade III (B) and (C) postoperative X-ray, after reduction, discectomy, graft, and cervical plate.

Figure 2: (A) T6T7 listhesis grade III preoperative X-ray (B) and (C) postoperative X-ray showing reduction and screws.

Traumatic injuries concerned cervical level in 57% of cases (Table 2).

| AO class | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C3 burst complete fracture | A4 | 1 | 1.1 |

| C3/C4 listhesis II | C | 1 | 1.1 |

| C4 complete burst fracture | A4 | 1 | 1.1 |

| C4/C5 listhesis I | C | 2 | 2.2 |

| C4/C5 listhesis II | C | 13 | 14 |

| C4/C5 listhesis II+C5 split fracture | C (C5:A2) | 1 | 1.1 |

| C4/C5 listhesis III | C | 6 | 6.4 |

| C4C5 listhesis I | C | 1 | 1.1 |

| C5 complete burst fracture | A4 | 3 | 3.2 |

| C5/C6 listhesis I | C | 2 | 2.2 |

| C5/C6 listhesis II | C | 8 | 8.6 |

| C5/C6 listhesis III | C | 3 | 3.2 |

| C5/C6 listhesis II | C | 1 | 1.1 |

| C6 complete burst fracture | A4 | 1 | 1.1 |

| C6/C7 listhesis I | C | 3 | 3.2 |

| C6/C7 listhesis II | C | 5 | 5.4 |

| C6/C7 listhesis II+C7 incomplete burst fracture | C(C7:A3) | 1 | 1.1 |

| C7/T1 listhesis I | C | 1 | 1.1 |

| C7/T1 listhesis II | C | 3 | 3.2 |

| L1 complete burst fracture | A4 | 2 | 2.2 |

| L1 split fracture | A2 | 3 | 3.2 |

| T12/L1 listhesis III+L1 wedge-compression | C (L1:A1) | 1 | 1.1 |

| L2 complete burst fracture | A4 | 2 | 2.2 |

| L2 incomplete burst fracture+L2L3listhesis II | A3(L3:C) | 1 | 1.1 |

| L2 split fracture | A2 | 2 | 2.2 |

| L3 complete burst fracture | A4 | 1 | 1.1 |

| L3 split fracture | A2 | 2 | 2.2 |

| L4 complete burst fracture | A4 | 2 | 2.2 |

| L3/L4 dislocation | C | 1 | 1.1 |

| L4 complete burst fracture | A4 | 1 | 1.1 |

| L4 split fracture | A2 | 1 | 1.1 |

| T10/T11 listhesis III | C | 1 | 1.1 |

| T11 chance fracture | B1 | 1 | 1.1 |

| T12 complete burst fracture | A4 | 2 | 2.2 |

| T12 chance fracture | B1 | 1 | 1.1 |

| T12/L1 listhesis II | C | 2 | 2.2 |

| T12/L1 listhesis III | C | 1 | 1.1 |

| T2/L1 listhesis III | C | 1 | 1.1 |

| T3/T4 listhesis III+T4 complete burst fracture | C(T4:A4) | 1 | 1.1 |

| T5 chance fracture | B1 | 2 | 2.2 |

| T6/T7 listhesis III | C | 1 | 1.1 |

| T7 chance fracture | B1 | 1 | 1.1 |

| T7/T8 chance fracture | B1 | 1 | 1.1 |

| T7/T8 listhesis II+T8 burst fracture | C(T8:A4) | 1 | 1.1 |

| T9/T10 listhesis IV | C | 1 | 1.1 |

| Total | 93 | 100 |

Table 2: Fracture type, AO classification and level.

The median time from admission to operating room was 21.06 ± 11.8 days (range 2-62) (Table 3).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| A | 14 | 15.1 |

| B | 13 | 14 |

| C | 15 | 16 |

| D | 24 | 25.8 |

| E | 25 | 26.9 |

| Died | 2 | 2.2 |

| Total | 93 | 100 |

Table 3: ASIA score outcomes.

Two patients died after surgery; 25 (27.5%, n=91) had an E ASIA score at discharge (Table 4).

| ASIA on admission, n (%) | Total | 25 (27.5) | 24 (26.4) | 15 (16.5) | 13 (14.3) | 14 (15.3) | 91 (100) | P- Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2 (8) | - | 3 (0.2) | 9 (69.2) | 13 (92.8) | 27 (29.7) | <0.001a | |

| B | - | 7 (29.2) | 8 (5.3) | 4 (30.8) | - | 19 (20.9) | ||

| C | 3 (12) | 9 (37.5) | 4 (2.7) | - | 1 (7.2) | 17 (18.7) | ||

| D | 11 (44) | 8 (33.3) | - | - | 0 | 19 (20.9) | ||

| E | 9 (36) | - | - | - | 0 | 9 (9.8) | ||

| E | D | C | B | A | Total | |||

| ASIA on discharge, n (%) | ||||||||

a* The relationship between ASIA grade at admission and discharge was statistically significant.

Table 4: Evolution in ASIA from admission to discharge.

The mean follow-up time was 11 months (range 3-18 months). After surgery, 15.3% (n=14) improved by at least 1 ASIA grade, 79.1% (n=72) were stable and 5.6% (n=5) worsened. Some complications were recorded on 36 (38.7%) patients (Table 5). There was no implant dislocation. Two patients (2.2%) died postoperatively during hospitalization. They had C4/C5 lesions. The global mortality rate of the series was 12% (n=11).

| Cervical spine (n; %) | Thoraco-lumbar spine (n; %) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggravation of preexisting myelopathy | 3 (3.2) | - | 3 (3.2) |

| Superficial wound infection | - | 10 (10.8) | 10 (10.8) |

| Cerebrospinal fluid leakage | - | 3 (3.2) | 3 (3.2) |

| Superficial wound dehiscence | - | 7 (7.5) | 7 (7.5) |

| Bedsores | 4 (4.3) | 9 (9.7) | 13 (14) |

Table 5: Complications after surgery.

In the developing world, traumatic injuries represent a significant disease burden and one of the leading causes of death in economically active adults. Moreover, as defined by disability associate life years (DALY), long-term morbidity from injuries in low-income countries is higher than morbidity caused by either cardiovascular conditions or malignancies [11]. We present here the description of the epidemiology and the current surgical management of TSIs in Lomé-TOGO, a West African francophone low-income country. Spinal injuries affect the young active segment of the population, which are crucial to the economy [4]. Our study showed a preponderance of males (91.4%). The mean age of our series was 35.92 ± 9.68 years old [12-14].

Traffic accidents are the leading cause of injury in developing countries, whereas falls are the leading cause of injury in developed countries [4,15,16]. Our series found that motorcycle and motor vehicle accidents were the most typical causes of TSI (85%), followed by falls (9.7%). In our conditions, many factors incriminated for traffic accidents were the poor quality of oldfashioned roads, non-compliance with traffic safety measures, and sometimes young men’s risk-taking with motor vehicles [4,17]. The cervical spine was the most common segment injured in our study (57%). This finding is in keeping with many authors [4,17-19].

At presentation, 31.2% of patients in our series had complete deficit (ASIA A). This finding is under the rates reported in Nigeria, 91.9% and 52.6%, respectively, by Obalum et al. and Yusuf et al. [13]. Our ASIA A rate is high than the rate of 22.1% of ASIA A at the admission foud by Sane et al. [17].

According to the AANS/CNS guidelines, available literature has defined « early » surgery inconsistently, ranging from <8 hours to <72 hours [20]. In our series, the median time from admission to the operating room was 21.06 ± 11.8 days (range 2-62). That time is too long from the AANS/CNS recommendation. Our median time is similar to Magogo et al. report of 23 days from admission to the operating room in Tanzania. Those findings could be explained by the fact that most low-income people have to pay out of their pocket because the rate of medical insurance coverage is low [8,13]. In the present study, only 17.2% of patients have public insurance, and 2.2% private insurance.

We performed three types of surgery: anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, anterior cervical corpectomy with tricortical iliac crest graft and plate, and poster lateral thoracic/ lumbar fusion. We did not do posterior cervical laminectomy with fusion. Implant availability for posterior cervical fusion was the principal driver of that decision in our limited resources. In our conditions, we could not do during the period of study, anterior lumbar spine corpectomy, and fusion, as well as upper cervical surgery.

In our series, 15.3% improved 1 ASIA grade after surgery. Similar to our results, Lövfen et al. from Botswana reported an Asia improvement rate of 16% [6]. In Tanzania, Magogo et al. found a rate of 17% [8]. These rates are low compare with higher-income countries. In Korea, Kim et al. [21]. reported a 47% of improvement rate. Mattassich et al. [22]. Reported a rate of 31% according to Magogo et al., these results in high-income countries should not be applied to an LMIC setting due to noticeable environmental differences. Despite the poor followup (11 months), outcomes were encouraging in our series.

Bedsores and superficial wound infections were the most typical complications in our series. Our infection rate (10.8%) is higher than 2.2% reported by Choi et al. in Cambodia [23]. Bedsores represented 14% of complications after surgery in our series. That rate is lower than 89.6% reported by Obalum et al. in Nigeria [4]. The mortality rate of 12% reported in our study is higher than 6.6% reported by Chen et al. in Taiwan and 10% reported in Botswana. On the other hand, our mortality rate is lower than 17% found in Ethiopia by Lehre et al. Despite the poor follow-up in our series (11 months), outcomes were encouraging. Others studies with long follow-ups are necessary to confirm these observations.

Traumatic spine injury is the result of a traffic road accident in our study. It occurs in young adults. Three surgeries were offered: anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, anterior cervical corpectomy with tricortical iliac crest and plate, and posterolateral thoracic/lumbar fusion. Despite limitations in medical resources, spine surgery appears promising in our country.

The retrospective nature of our work has many limitations. The dependence upon the quality of recorded data in the medical files was the most obvious. We conducted a single-center epidemiological study. This study could not determine the incidence and prevalence of TSI in our country. Unfortunately, postoperative imaging was not usually obtained due to cost.

None declared

None

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

Citation: Doléagbénou AK, Djoubairou BO, Ahanogbé MKH, Egu K, Békéti AK, Kpélao E, et al. (2022) Surgical Management of Traumatic Spinal Injuries in Sylvanus Olympio Teaching Hospital. J Anesth Clin Res. 13:1075

Received: 15-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. JACR-22-18860; Editor assigned: 21-Jul-2022, Pre QC No. JACR-22-18860 (PQ); Reviewed: 04-Aug-2022, QC No. JACR-22-18860; Revised: 11-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. JACR-22-18860 (R); Published: 17-Aug-2022 , DOI: 10.35248/2155-6148.22.13.1075

Copyright: © 2022 Doléagbénou AK, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.