Andrology-Open Access

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0250

ISSN: 2167-0250

Research Article - (2022)

Objective: Androgenic Anabolic Steroids (AAS) abuse has increased among adult men and has a negative impact on sexual and reproductive health. Studies or guidelines outlining the management pathways for AAS abuse are currently unavailable. We aimed to confirm the deleterious effects of AAS abuse on sexual health and fertility, monitor the spontaneous recovery, and demonstrate the effects of treatment regimens on recovery.

Methods: We enrolled 520 patients with a confirmed history of AAS intake within 1 year of presentation and evaluated their symptoms, hormones levels, and semen every 3 months till 12 months. All patients ceased using AAS and were monitored for spontaneous recovery in the first 3 months; if they showed no recovery, they were randomized to undergo either continued observation or commence medications. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), hormone levels, and semen at presentation and at each 3 months visit were measured and compared between the treated and untreated patients.

Results: The most common presentation (84%) was a combination of sexual symptoms. Some patients (18%) were infertile. Most patients (90%) reported low levels of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and total testosterone. After the 3-month observation, most patients (89%) started treatment, but some (11%) continued observation only. IIEF values and hormone levels in the treated group showed significant improvements (p<0.005). Semen analysis was abnormal in 79% of patients, and 85% of who presented with infertility failed to conceive despite treatment.

Conclusion: AAS abuse negatively impacts sexual activity and fertility. Treatment yields a faster recovery than nontreatment. Infertility may persist despite treatment. It is an urgent call for andrology and men health scientific bodies to work on guidelines for specific treatment AAS abuse adverse effects.

Androgenic anabolic steroids; Fertility; Index of erectile function

The use of Performance-Enhancing Drugs (PEDs) to enhance sports, performance and/or physical appearance has progressively increased among young and middle-aged men. One of the most abused PEDs are Androgenic Anabolic Steroids (AAS) [1]. AAS abuse results in supraphysiological testosterone levels with eventual negative effects on the Hypothalamic-Pituitary Axis (HPA), leading to a unique condition known as Anabolic Steroid– Induced Hypogonadism (ASIH) and manifestations of hormonal disturbances, gynecomastia, testicular dysfunction, and infertility, all of which are well-described but poorly understood [2-5]. The lifetime prevalence of AAS abuse is estimated to be 6% in men; therefore, the resultant adverse effects constitute a public health concern, since these medications can result in deleterious health effects [6,7]. Despite the AAS abuse is underreported to health authorities in many communities and up to 50% of AAS- users do not disclose their use to their physician, it becomes an alarming global phenomenon and well noticed in many other regional and global communities [8-11]. Spontaneous recovery of the negative effects caused by AAS abuse can be achieved after discontinuing usage, but this requires several months to years; however, in many patients, the effects may be permanent [12-14]. Presently, the peerreviewed literature contains limited information describing the demographics, characteristics, and psychologic profile of AAS users. Furthermore, no comprehensive management recommendations or guidelines have been proposed for the treatment of AAS-induced adverse effects, such as infertility and ASIH, and all available medication regimens are off-label [15-22]. The understanding of this condition has been hindered by a lack of publications, with only a few large-volume studies preclude the development of a meta-analysis studies. Moreover, in our region (the Middle East), studies on the prevalence and significant negative effects of this condition, as well as the effects of management strategies are unavailable. Therefore, we aimed to provide objective evidence of the deleterious effects of AAS abuse on sexual health and fertility and the possible effects of treatment medications on early recovery from adverse effects due to AAS abuse.

Patients and methods

This single-center prospective randomized study was conducted on patients who presented to the urology–andrology clinic, at Burjeel Hospital, Abu Dhabi, UAE between June 2012 and June 2019, all included patients had confirmed intake of non-prescribed AAS in the last year and complained of sexual dysfunction and or infertility.

Inclusion criteria

• History of intake of non-prescribed AAS on any occasion over the year preceding presentation at our clinic.

• Sexual symptoms (erectile dysfunction, low sexual desire, defective orgasm, and or defective ejaculation) for at least 3 months and/or infertility (trying to conceive for >1 year before presentation at our clinic).

• Discontinuation of androgen intake after study enrollment.

• Continuous follow-up for 1 year after study enrollment.

Exclusion criteria

• Sexual symptoms or infertility without a definite history of androgen use or caused by other than AAS abuse.

• Loss to follow-up before completing 1 year.

• Relapsed androgen uses after study enrollment.

Tests and examinations

• For evaluation of sexual symptoms, we used the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) and its sub-domains (Erection, Orgasm, Desire, and Sexual Satisfaction) while for infertility, we used semen analysis.

• Follow-up examinations of testicular size by office ultrasound.

All patients underwent the same serum hormonal tests, including measurements of Follicular Stimulating Hormone (FSH), Luteinizing Hormone (LH), prolactin, estradiol, testosterone, and Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG), at presentation and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of follow-up. Blood tests were performed between 7 am and 11 am. Semen analysis was performed (after 48 h of abstinence) for all patients at intervals of 3 months for a period of 12 months. All patients were followed up for 12 months after initial presentation. All hormones assessment used (Electrochemiluminescent Immunoassays-ECLIA).

Patient treatment pathways

• All patients underwent a mandatory three-month observation before starting treatment medications.

• The patients had the option to either continue the observation or start receiving treatment medications if they could not tolerate AAS withdrawal symptoms. The patients were randomized to untreated and treated groups based on their choice.

• Patients were allowed to start treatment only if they showed at least moderate to severe symptoms with confirmed objective findings (IIEF values, hormones levels, and/or abnormal results in semen analysis).

• Treatment courses of 2-3 months continued until the patients showed improvement of symptoms, hormones levels, and or clinical pregnancy for infertility.

• Treatment was repeated if the patients showed any relapse of symptoms or deterioration of hormone levels during followup intervals.

Medications and treatment regimens

• The patients were informed that all medications were off-label, and in the absence of specific guidelines, the medications and the duration of treatment were based on data from similar studies on the treatment of adverse effects of AAS abuse [15-22].

• The treatment regimen included human chorionic gonadotrophin HCG1500 IU injections/three times weekly and Clomiphene Citrate (CC) 25 mg tablets once daily or 50 mg tablets on alternate days, both of which were used for low testosterone and or oligospermia, or azoospermia.

• The duration of treatment was initially 30 days, and subsequently, treatment was either continued at the same doses or titrated according to the results of follow-up hormone tests (FSH, LH, testosterone, and estradiol) that were performed monthly during treatment and seminal fluid analysis that was performed every 3 months.

• Patients who showed gynecomastia with ASIH and/or infertility at presentation were administered tamoxifen tablets (10 mg twice daily) instead of CC.

• Patients who showed gynecomastia with high estradiol levels and/or low Testosterone/Estradiol (T/E) ratios were treated with letrozole (2.5 mg) or anastrazole (1 mg) tablets once daily for 30 days, and the dose was subsequently titrated according to the results of follow-up hormone tests.

• FSH injection (75 IU thrice weekly) was administered to treat infertility that did not respond to LH or clomiphene citrate alone. The duration of treatment was initially 3 months, and treatment was subsequently continued or stopped depending on the results of semen analysis.

Informed consent and ethics approval

Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to study enrollment. The privacy and confidentiality of individual patient data were maintained throughout the study period and post-study. Ethics committee approval was obtained before patient enrollment.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 16.0. Statistical analysis was performed by comparing the patient characteristics before treatment initiation and after treatment completion. All baseline characteristics were described for the patients treated. For continuous variables, data were presented as mean ± SD. For categorical data, numbers and percentages were used in the data summaries, and the data were presented in the form of tables. Repeated-measures analysis of variance and Chisquared tests were performed to compare the recovery of symptoms and hormone levels between treated and untreated patients. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

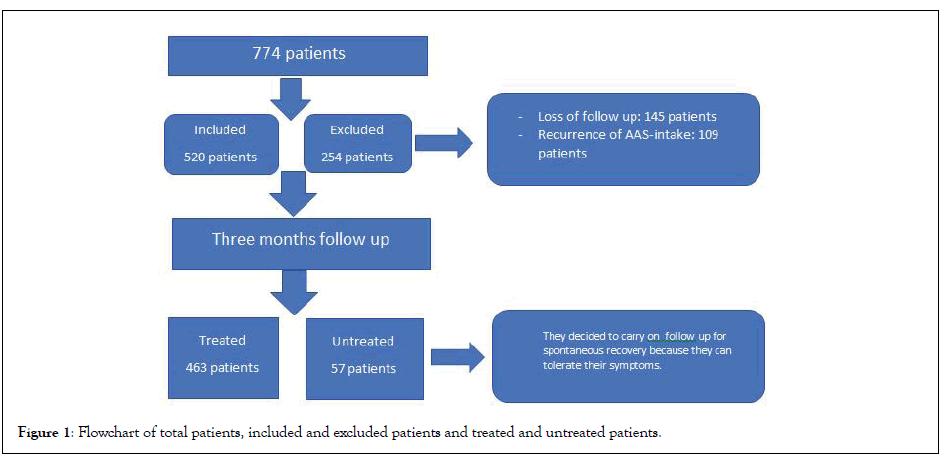

Overall 774 patients who presented with a confirmed history of intake of non-prescribed androgens were screened. Data of 520 patients were used for statistical analysis since 254 patients were excluded based on the exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Mean age of the included patients was 32 ± 4 years, with the majority (52%) being aged between 20 and 30 years, and 78% of the patients were married (Table 1). Presenting symptoms included loss of sexual desire (72%), ED (68%), gynecomastia (35%), reduced orgasmic satisfaction (23%), ejaculatory disorders (17%), and combinations of these symptoms (84%). Based on IIEF assessments, 56% (n=291) of the patients were categorized as having severe ED (1-10; mean, 7 ± 2), 27% (n=140) had moderate ED (11-16; mean, 14 ± 2), and 17% (n=88) had mild ED (17-21; mean, 19 ± 1). The IIEF subdomain scores at the time of presentation were as follows: erectile function, 14 ± 3; orgasmic function, 3 ± 2; sexual desire, 3 ± 2; intercourse satisfaction, 4 ± 2; overall satisfaction, 3 ± 2; and total IIEF, 27 ± 5. Approximately 18% (n=74) of the patients had infertility. All patients underwent the initial mandatory 3-months observation; subsequently, 463 patients (89%) decided to commence treatment because of sexual symptoms or infertility (treated group). The remaining 57 patients (11%) decided to continue without treatment until the end of the follow- up (untreated group). IIEF evaluations revealed no significant changes between the treated and untreated groups at presentation and after 3 months of watchful waiting, although statistically significant differences in favor of the treatment group were evident at the 6-, 9-, and 12-month assessments (Table 2). The untreated group showed no significant difference between the IIEF value at presentation and those at 3, 6, and 9 months (p>0.05), with a significant change appearing only at the 12-month assessment (p<0.005). However, the IIEF values in the treated group showed significant improvements at the 6-, 9-, and 12-month assessments (p<0.005).

Figure 1: Flowchart of total patients, included and excluded patients and treated and untreated patients.

| Parameters/characteristics | N=520 |

|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 32 ± 4 |

| 20-30 | 270 (52%) |

| 30-40 | 177 (34%) |

| 40-50 | 73 (14%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 406 (78%) |

| Unmarried | 114 (22%) |

| Courses per year | |

| 1 | 62 (12%) |

| 2 | 182 (35%) |

| 3 | 198 (38%) |

| >3 | 78 (15%) |

| Duration of courses (weeks) | |

| 01-08 | 42 (8%) |

| 04-08 | 120 (23%) |

| 08-12 | 332 (64%) |

| >12 | 26 (5%) |

| AAS intake recommended by | |

| Coach | 395 (76%) |

| Self | 78 (15%) |

| Friends | 47 (9%) |

| Purpose of AAS use | |

| Enhanced fitness training | 328 (63%) |

| Enhanced physical appearance | 130 (25%) |

Note: AAS: Anabolic Androgenic Steroids

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the patients.

| Time of examination | Treated (n=463) | Untreated (n=57) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| At presentation | 10 ± 1 | 10 ± 2 | 1.0000 |

| 3 months | 10 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 | 1.0000 |

| 6 months | 18 ± 4 | 10 ±1 | <0.0001 |

| 9 months | 20 ± 2 | 10 ± 2 | <0.0001 |

| 12 months | 24 ± 2 | 12 ± 4 | <0.0001 |

Table 2: Mean IIEF values in the treated and untreated group at different follow-up intervals.

Ultrasound measurements of testicular size showed small testes (<12 cc) in 177 patients (34%) at presentation (mean size, 8 ± 1.6 cc), 213 patients (41%) at 3 months (mean size, 7 ± 1.8 cc), 135 patients (26%) at 9 months (mean size, 9 ± 1.0 cc), and 109 patients (21%) at 12 months (mean size, 11 ± 1.5 cc). At the end of the year, 61% (35/57) of the patients in the untreated group still had small-sized testes, while the corresponding proportion in the treated group was 20% (93/463; p<0.001). The baseline evaluations of hormonal levels showed low serum LH levels in 489 patients (94%; mean, 0.01 ± 0.2 mIU/mL), low serum FSH levels in 478 patients (92%; mean, 0.1 ± 0.2 IU/L), low total testosterone level in 468 patients (90%; mean, 3.3 ± 1.2 nmol/L), low SHBG level in 374 patients (72%; mean, 12 ± 3.2 nmol/L), and high estradiol level in 286 patients (55%; mean, 45 pg/mL). Hormone evaluations showed no significant differences between the treated and untreated patients at presentation and at the 3-month follow-up; assessments performed at 6, 9, and 12 months showed significant differences in favor of the treatment group (Table 3). The untreated group showed no significant differences in LH, FSH, and testosterone levels at 3 and 6 months (p>0.05) in comparison with the values at presentation, while significant differences were only seen in the FSH and LH levels at 9 months and in the testosterone levels at 12 months (p<0.005). Contrastingly, the treated group showed significant improvements in FSH, LH, and testosterone levels at 6, 9, and 12 months (p<0.005). Semen analysis revealed abnormal semen characteristics in 411 patients (79%), of which 337 patients (82%) showed a combination of oligospermia, azoospermia, and asthenozoospermia. Oligospermia (<15 M/mL) was noted in 279 patients (68%; mean, 6 ± 1.8 M/mL), and azoospermia in 33 (8%) patients. Subsequent semen analyses showed no significant differences in the oligospermia rate between the initial value and the values obtained at 3 months (68% vs. 73%; p<0.108) or at 6 months (68% vs. 64%; p<0.107), and significantly lower rates at 9 months (68% vs. 53%; p<0.001) and at 12 months (68% vs. 45%; p<0.001). The rate of oligospermia at presentation was 71% in the treated group and 69% in the untreated group (p=0.6795). However, at the 12-month assessment, the rate was significantly better in the treated group (33% vs. 55%; p=0.001). All azoospermie patients (n=33) chose to start treatment; 11 and 16 patients showed sperm in their ejaculate at the 9- and 12-month assessments respectively, but all still showed oligospermia (<10 M/mL). Among the 94 patients who presented with infertility (18%), 61 had oligospermia and 33 had azoospermia. All received treatment, but only 14 (15%) achieved successful pregnancy at 12 months (p<0.001). All patients who presented with azoospermia continued to show infertility at the end of the follow-up period. Among the 463 treated patients, 150 (32%) maintained the improvements in symptoms and hormone levels until 12 months after receiving treatment with one course (1-3 months), while 210 (45%) showed persistence or relapse of symptoms and required continuation or resumption of medical treatment for 4-6 months; the remaining 103 (23%) required >6 months of treatment and still showed persistent abnormal symptoms or hormones at 1 year of follow-up. Patients who required only one treatment course had an AAS abuse duration of <3 months (mean, 6 ± 1.1 weeks), while those who required more treatment courses had a longer history of AAS abuse (mean, 12 ± 2.1 weeks; p<0.001). Moreover, the average timing of presentation among those who required one course of treatment was 6 ± 1.5 weeks after the last dose of AAS versus 10 ± 2 weeks for those who required more than one course of treatment (p<0.001). Gynecomastia was observed in 182 patients (35%), mostly with other sexual symptoms; it was more common in those with longer AAS abuse histories (>12 weeks) (mean, 14 ± 1.5 weeks) than in those with shorter histories (mean, 7 ± 2 weeks) (p<0.001).

| Time of examination | Treated(n=463) | Untreated(n=57) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSH (mlU/mL) | |||

| At presentation | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 1.0000 |

| 3 months | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.0000 |

| 6 months | 6.4 ±16 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | <0.0001 |

| 9 months | 5.8 ± 1.8 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | <0.0001 |

| 12 months | 7.4 ± 22 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | <0.0001 |

| LH (mlU/mL) | |||

| At presentation | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.7218 |

| 3 months | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.1322 |

| 6 months | 5.2 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | <0.0001 |

| 9 months | 4.8 ± 2.2 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | <0.0001 |

| 12 months | 6.4 ± 2.0 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | <0.0001 |

| Testosterone (nmol/L) | |||

| At presentation | 7.1 ± 1.2 | 7.3 ± 1.0 | 0.2278 |

| 3 months | 6.1 ± 2.2 | 7.1 ± 1.2 | 1.0000 |

| 6 months | 12.1 ± 1.2 | 8.2 ± 1.4 | <0.0001 |

Table 3: Average values of hormone levels between treated and untreated group at different time intervals.

Our study confirmed the increasing global trend of AAS abuse in the young population; the largest user population in our study was 20-40 years old, consistent with results for other global and regional studies, such as those conducted in Saudi Arabia [9]. Surprisingly, despite cultural differences worldwide, the aims of AAS users are almost identical. Most of our patients’ decisions to use AAS were driven by their coaches’ advice and friends’ recommendations. Their primary aim was to improve training fitness and physical appearance [8-11]. The commonest AAS used were Nandrolone/decadurabolin and testosterone/ sustanon and usually a combination of oral and injectable drugs. The most common source of AAS for our patients was their coaches; only some patients received their medicines through online purchases, which may be the main sources of AAS in other societies [23]. These medicines were usually not registered, illegally imported from the international market without any consideration for appropriate storage and dispensed without prescription by nonlicensed personnel and coaches. Most patients (83%) complained of moderate to severe sexual symptoms, while a substantial proportion (18%) also complained of infertility; this explains why such a large majority of patients preferred to start early treatment. Additionally, while a small proportion of patients showed spontaneous recovery after 3 months of watchful waiting, most still complained of severe symptoms and had low hormone levels, while the untreated group continued to show the same symptoms until the end of 12 months. This confirms the findings of previous studies on the long-term suppressive effects of AAS abuse [4,5,24]. Although Lykhonosov et al. Reported a high recovery rate of 79% after 3 months, but their study has small patients number and were evaluated over a short follow- up period [25]. Other remarkable findings in our study included the high rate of abnormal semen findings (79%), the significant delay in spontaneous recovery in the untreated group, and the considerable percentage of patients presenting with infertility. Although all patients presenting with infertility were treated, the outcome was disappointing since only 15% of the patients reported a successful pregnancy before the end of the 12 months follow-up period, again highlighting the long-term negative influence of AAS abuse on fertility and the need for longer-thanexpected time for recovery [4,5,24]. These findings have also been well documented by Windfeld-Mathiasen et al., who reported that AAS use was associated with a temporary decline in fertility but, over a follow-up period of 10 years, the fertility rate and prevalence of assisted reproduction among AAS users were close to those in the background population [26]. Conversely, our study also provided evidence that longer and more frequent AAS courses and delays in presentation are negative predictors of early spontaneous recovery and may indicate the need for long and frequent treatment. In our study, the treatment regimens used for ASIH, infertility, and gynecomastia were well tolerated by all patients and were according to the recommendations of many similar studies [15-22]. However, in the absence of specific guidelines to treat the adverse effects of AAS use, there is uncertainty regarding the use of specific medicines and doses for individuals, which explains why 9% of patients preferred to continue with observation only despite complaining of significant symptoms.

Our study characterizes the harmful effects of AAS abuse on sexual and reproductive health, especially in patients who use AAS repeatedly and over prolonged periods. These patients show a significantly high rate of sexual symptoms (ED and loss of desire), and untreated patients show a very low recovery rate over 12 months. There is also a high incidence of abnormal semen with a low recovery rate, especially in patients with azoospermia. Infertility may persist even after 1 year of treatment.

The use of medications is well tolerated, and patients who receive them show significantly faster recovery of AAS withdrawal symptoms and hormone levels than untreated patients but considering the absence of relevant guidelines and the off-label use of medications, insights for individual-specific usage of these agents are not available, highlighting the urgent need for specific treatment guidelines.

• Longer follow up period is needed for both treated and untreated patients and the need for evidence-based medications for the treatment.

The lack of basic levels of hormones, semen analysis before AAS use, the need for longer follow up period and being single center study.

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Hashimi MA (2022) The Deleterious Effects of Androgenic Anabolic Steroid Abuse on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Comparison of Recovery between Treated and Untreated Patients. Andrology. S2:004.

Received: 21-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. ANO-22-16337; Editor assigned: 25-Mar-2022, Pre QC No. ANO-22-16337 (PQ); Reviewed: 08-Apr-2022, QC No. ANO-22-16337; Revised: 18-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. ANO-22-16337 (R); Published: 27-Apr-2022 , DOI: 10.35248/2167-0250.22.S2.004

Copyright: © 2022 Hashimi MA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Sources of funding : NO