Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy

Open Access

ISSN: 2161-0487

ISSN: 2161-0487

Original Research Article - (2021)Volume 11, Issue 2

The unprecedented lockdown in Lithuania due to COVID-19 pandemic lasted for 92 days from March 15th to June 16th, 2020 producing profound changes in lifestyles and routines of population. It is not clear, what emotional responses this evoked in different groups of population. The goal of the current study was to research the emotional changes of the different gender and age groups of Lithuania population during the quarantine. From March 30th to June 8th, 2020 representative samples of Lithuanian citizens 18–74 years of age were surveyed five times on their emotional states. In total, 2634 participants answered questions from Gallup’s Global Emotions Report to evaluate their anxiety, sadness, anger, enjoyment, calmness, stress, and physical pain. Significant gender and age differences on emotion prevalence were found. During the five polls taken, more women were found to report feeling stressed, anxious, sad, and in more physical pain than men. Evaluations of anger, enjoyment, and calmness revealed no significant gender differences. Emotions were found to differ significantly between three age groups (18–29, 30–49 and 50–74). Contrary to expectations, the biggest negative impact of quarantine was found in the youngest group aged 18–29 years it showed highest prevalence of stress, anxiety, and sadness of all age groups. Individuals of different gender and age reacted to quarantine in a different way. These findings might provide some insight into factors affecting emotional reactions and help to plan better targeted social interventions in the future.

Coronavirus; COVID-19; Pandemic; Quarantine; Emotion dynamics

Quarantine and isolation help to prevent the spread of contagious diseases by restricting people’s movements [1,2]. Isolation separates sick people from healthy people, whilst quarantine segregates individuals exposed to the disease. Following the announcement that coronavirus (COVID-19) is a pandemic [3] countries started implementing national quarantines. China was the first to lockdown their city of Wuhan prohibiting any public movement and closing workplaces [4]. Similarly, strict measures were taken in Italy – the epicenter of the coronavirus in Europe ‒ as the whole country went into lockdown [5]. Other countries with lower infection rates like Lithuania had more lenient rules [6]. Schools, restaurants and some other workplaces were closed, but public movement wearing face masks was allowed in most places. Physical constraints of quarantine and social isolation of people have been found to create psychological distress [7]. Governments aim to control the pandemic, but they need guidance on dealing with people’s mental health. To provide effective recommendations, more research on the psychological impact of quarantine is needed. Useful insights into this were found during the SARS, Ebola, and MERS pandemics, that can be applied to coronavirus pandemic. However, each viral pandemic is said to be unique and to have diverse consequences; thus, more research, specifically on COVID-19, is needed. Unfortunately for researchers, COVID-19 has affected everyone’s lives and made it difficult to distinguish control groups of zero exposure. Additionally, a big variety of national quarantine regulations the exploration of universal trends of emotional response. Other limitations mentioned in the review by Brooks are inappropriately used clinical diagnostic tools for assessment of quarantine’s impact, and the population samples assessed are poorly representative of the general population. For instance, [8] used a post-traumatic stress disorder diagnostic scale to assess post-traumatic stress after the SARS pandemic, even though quarantine is not qualified as trauma in the DSM- 5 diagnosis for PTSD. Such assessment of quarantine’s impact on people’s mental health could have missed out on less severe symptoms from this high-threshold clinical scale. In terms of study samples used, some had a small sample size [9] or participants were undergraduate students [10], while others assessed only health care workers [11-13]. So, in our study we sampled a representative group of Lithuanian citizens between 18 to 74 years of age. Single item questions for selected emotions were used as part of an opinion poll in fives waves of research covering a time span of 70 days. This allowed us to assess the dynamic of emotions in different genders and age groups that represent the general population of Lithuania.

Three major trends emerged from studies on emotions and mental health during previous pandemics: people show increased anxiety, depression, and stress symptoms. A study by Liu explored how the SARS outbreak in Beijing had influenced medical staff‘s psychopathology for 3 years post-pandemic. In one study, physicians and nurses who had high pandemic exposure were split into two groups based on having been quarantined or not, and were surveyed using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D) [14] and the Impact of Event Scale- Revised (IES-R) [15] for PTSD symptoms. Health care workers from the Liu study had been quarantined for around 10 days together with SARS patients and were taking care of them. They could not see their families and were at high risk of infection, which could have inflated their psychopathology symptoms throughout time. They were tested three years after that period. It appeared, that participants who had been quarantined and had previous traumatic experiences had higher depressive symptoms. Being 35 years old or younger and being single was also predictive of higher depressive symptoms post-pandemic.

Anxiety increase was recorded and analyzed by [16] in Korea during isolation periods of MERS and for 4–6 months afterwards. People infected with MERS were compared against healthy but isolated people on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD- 7) [17] and the Korean version of State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAEI) [18]. During isolation, 47.2% of MERS patients and 7.6% of quarantined people had anxiety symptoms, when general population prevalence was around 3.3% [16]. After 4–6 months post-pandemic, numbers decreased to 19.4% for MERS patients and 3.0% for isolated healthy people, showing possible recovery to normal anxiety levels. Anger trends were similar to anxiety, but with a bigger decrease. However, reported that around 30% of people did not agree to answer questions on the phone and were swearing at the researchers. If this had been included in the data analysis, it could have shown higher anger results in the study. The prominent psychological impact of quarantine is increased stress symptoms, as explored by [8]. A web-based survey with questions from PTSD [15] and depression (CES-D; [14] scales was distributed in Toronto, Canada around 36 days after SARS quarantine. More than half of respondents were health-care workers aged 26-45, the majority having college level education or higher, and most had medium to high levels of income. The isolation period was on average 10 days, and survey respondents were questioned on knowledge and understanding of the reasons for the quarantine, what they knew about infection control measures and where they found that information. Researchers used cut-off points that clinically diagnose PTSD and depression disorders, and found that 28.9% and 31.2% of quarantined people met the criteria for PTSD and depression accordingly. Depressive and PTSD symptoms were strongly correlated together (r=0.78) and an increase of both was predicted by household income ‒ lower income led to more pronounced symptoms. Neither age, level of education, nor career choice had any influence, although longer duration of quarantine significantly predicted higher PTSD symptoms. No such trend was found with depression levels, however the study participants were isolated only for around 10 days and we might suppose that different results could emerge from longer quarantine periods.

The aforementioned findings of increased anxiety, depression and PTSD symptoms due to quarantine or pandemics generally might depend on certain risk factors. According to Brooks, an extensive literature review, health-care workers were more severely distressed than general public, especially if they were quarantined. In fact, most studies report higher risks for health-care workers during pandemics, but the majority of them do not compare their result with the results of the general public. The study that did so found no significant correlations between being a health-care worker and showing greater PTSD symptoms Hawryluck. This could be because health-care workers had a better understanding of quarantine measures and had a better understanding of the situation. Another risk factor mentioned by some researchers Jeong is a history of mental illness. People who have pre-existing mental conditions are more at risk during quarantine, as they have weak emotional control and rely more on social support. This implies that they require additional support to protect their mental health during quarantine and isolation. Some studies suggest that the elderly is at the greatest risk, not only because of being in the COVID-19 health risk group, but also because they are more susceptible to depression and anxiety. A longitudinal study found a pattern of social disconnectedness predicting perceived isolation which in turn predicts depression and anxiety symptoms. In other words, having a smaller social network or fewer social interactions leads to loneliness and perceived lack of support, which predict severity of depression and anxiety. Due to coronavirus regulations to stay at home, the elderly is put at greater risk of feeling lonely, unsupported, depressed and anxious about themselves and others. An alarming finding from researchers [19] suggests that perceived social isolation has the same detrimental effects as real physical isolation. Their experiments with isolated non-human social species show multiple physical damages, especially on the HPA axis that regulates sleep, mood, and stress. So, since the elderly were put at actual physical isolation and perhaps already had fewer social interactions, the risk only increases.

Stressors for emotional distress resulting from quarantine have been summarized in the systematic review of Brooks. Duration of quarantine is one of the factors influencing PTSD symptoms, anger, and avoidance behaviors as seen from comparisons of people quarantined for more or less than 10 days. It is yet unknown how long-term COVID-19 quarantines of 2 months or longer will impact on people’s emotions. During the SARS pandemic, people felt bored and frustrated in home isolation, having restricted contact with loved ones, with routine activities coming to a halt. Psychological distress was been intensified due to inadequate supplies of food, water, and accommodation for some people, as well as restricted to medical care not related to SARS. People were angry and confused when responsible health- care authorities spread inadequate information and unclear guidelines during the SARS pandemic. Lack of transparency from such authorities and explanation for their course of actions lead to violation of quarantine rules and it decreased the public’s trust [7]. One of the major factors influencing psychological distress is financial losses due to quarantine as people are unable to work, have little savings, and so on. It is also a risk factor for increased anger and anxiety symptoms, lasting months after quarantine [16]. Hawryluck found that low income before quarantine predicts higher PTSD and depression symptoms, so it could be assumed that these people might experience even higher symptoms by losing money during quarantine. They have more to lose as their household incomes are lower and it predicts higher psychological distress. The stigma surrounding risk groups and people of high exposure to the virus adds to psychological distress after quarantine. Multiple studies mentioned in Brooks et al. (2020) review have found stigmatization of people who have been quarantined during previous SARS outbreaks. Participants reported people avoiding them, treating them with fear and suspicion, making comments about them. Similarly, during the Ebola outbreak some people were unable to resume their jobs as it seemed too risky for them or because colleagues expressed fear of contagion.

Gender differences

Multiple studies have observed gender differences in the prevalence and severity of depression and anxiety symptoms. Globally the female to male ratio is 1.7:1 as women are almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with depression than men [20]. Multiple studies across countries find similar prevalence, indicating that biological sex differences have more influence than socio-economic factors. The main explanation is that women experience hormonal fluctuations across life during the stages of puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause, which could trigger the onset of depression. Women are more emotional and report depression symptoms more often than men, who externalize their feelings in such ways as anger or misuse of alcohol [20]. Gender roles are important, as men and women have different social needs, which result in different behaviors when unmet. Women report higher loneliness and depressive symptoms as their social needs are more complex and demanding [21]. Meanwhile, men are more reluctant to directly admit to feeling lonely as they grow up and they are expected to be more socially independent. An electroencephalography (EEG) study [22] found gender differences in a threat startle paradigm measuring neural-level sensitivity, and its link to anxiety and panic symptoms. It was found that women have higher startle potentiation in both predictable and unpredictable threat conditions compared to men. Females also reported higher panic symptoms in anticipation of an unpredictable threat, showing higher anxiety levels concerning unpredictable future events. Across both genders, greater panic symptoms were associated with higher startle potentiation in an unpredictable threat condition, but no significant link was found in predictable condition. This indicates that genders differ in panic symptoms experiences because they show different startle reflex in anticipation of unpredictable physical threats. Yet both men and women with heightened sensitivity to unpredictable threats can show greater panic and anxiety symptoms due to increased startle potentiation did not give any suggestions for future follow-up studies, but we think their findings might be put to the test by researching gender differences in emotional reactions during COVID-19.

Age

A longitudinal study of the elderly aged 57-85 years found associations between social isolation and disconnectedness on anxiety and depression symptoms [23]. The fewer social connections and activities they had, the more anxious and depressed they felt. Even though no younger people were recruited for comparison in this study, it still shows an increased risk for the elderly to be more anxious and depressed. However, not only older people feel lonely and sad, more than half of adolescents say they “sometimes feel lonely” too [21]. During adolescence, youngsters explore which friendships work, how their expectations are met, and so on. Yet the elderly, aged 80 years and more, feel lonely more often, as their personal networks shrink with time. Feelings of loneliness serve an evolutionary function to motivate people to reconnect with others. It motivates both young and old people to be more socially active, seek out support when needed and enjoy life by sharing it with others. Interesting differences on PTSD prevalence were observed by [24] across the lifespan of men and women. The highest prevalence of PTSD in men was at 41–45 years of age, for women at 51-55 years, whilst for both the lowest were at 71-75 years. Men have quite stable levels of PTSD risk, yet it peaks in early 40s as they usually take on more responsibilities in life (work, family, etc.) or potentially reach a midlife crisis. Women have an increased risk around early 20s ‒ a time of frequent changes (career, pregnancy) combined with social pressures on “being a modern woman“. Both genders aged 60 and above start showing decline of PTSD risk as they are thought to accept their imminent death and use early life experiences to cope with it. Using wisdom of retrospect, they usually solve the crisis between ego and despair of old age which shows in lower PTSD symptoms [24].

The negative consequences of quarantine are increased anxiety, depression, and stress symptoms, which might last long after the quarantine ends. Nine percent of health-care workers remained highly depressed 3 years after SARS quarantine [11]; MERS patients and healthy quarantined people stayed anxious 4-6 months after isolation [16]; up to 36 days after SARS quarantine high PTSD symptoms were still prevalent amongst the general population [8]. Longitudinal studies on emotional change during COVID-19 pandemic are still in progress, although China has shared their first analysis. Wang have surveyed the general Chinese population once when number of infections were rapidly increasing, and a month later when they were declining. More than 1,700 people responded to the survey, yet only around 300 people responded both times; remaining people responded once, either first or second time. Stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms were measured using the IES-R (Weiss, 2007) and Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) [25] as in previous studies, yet contrary results were found. None of the scores, except for PTSD scale, differed significantly between the first and second time of questioning. Only PTSD scores were significantly lower the second time, yet both times they were high enough to indicate strong presence of symptoms. The researchers assumed that it was probably due to rapid and decisive measures taken by Chinese government that people’s emotions remained stable [10] Additionally, people aged 12 to 21.4 years had higher PTSD scores than those aged 49.6 to 59 years. Students reported struggling to study remotely, expressed uncertainty and stress about their school or college exams.

An explorative paper has been issued by early career psychiatrists proposing an emotional curve framework that predicts emotion change during COVID-19 [26]. Young practitioners from World Health Organization regions discussed their countries’ mental health systems, preparations for coronavirus, economic plans, etc. An extensive literature review was combined with data gathered from country respondents and a conceptual framework was created. After working on feedback, a final version of emotional curve with double-peak emotional distress has been conceptualized. It shows an initial distress to the pandemic, then community growing resilience, and another distress wave coming post-pandemic as mental disorder prevalence increase. The most prominent consequences would be the aforementioned internal psychological struggles, such as anxiety, depression, and acute stress, as well as relapse to preexisting mental conditions. According to Ransing, the second peak of distress comes either due to second wave of COVID-19 cases, or people losing loved ones, or big economic and social disruptions happening. A phenomenon called ‘emotional contagion’ is also at play when people spread their anxious, angry or other mood across populations. It easily happens in today’s digitalized and global world, especially on social media platforms where people share their thoughts and feelings with thousands, indirectly ‘infecting’ them with their emotions.

China was the first country hit by COVID-19 revealing the impact it had on communities, psychologically and socially. A web-based study by [27] surveyed China’s residents on their psychiatric symptoms and feelings of returning to work. Additionally, to the diagnostic measures for anxiety, depression, and stress, questions on COVID-19 preventative hygiene recommendations and organizational measures were asked. Higher psychiatric symptoms were found to be associated with poor physical health and viewing return to work as a serious health hazard. As expected, adherence to hand hygiene recommendations, wearing face masks, and seeing safety improvements in workplaces meant people showed less severe psychiatric symptoms. Counterintuitively, returning to work did not result in increased severe stress, but workers group showed much lower prevalence of symptoms compared to previous China‘s population surveys [27]. This could be because of very strict preventative and safety measures implemented nationally in China that contrast with much milder regulations when people resumed working again.

The present study explores how the general population of Lithuania felt during COVID-19 pandemic during the national quarantine. From 30th of March to 8th of June, 2020 a representative group of Lithuanian citizens 18-74 years of age were surveyed five times on their emotional states. The goal of the current study was to research the emotion changes of the population of Lithuania during quarantine. Based on previous studies we expected to find certain trends in emotional reactions to COVID-19 that is different reactions between men and women, and between age groups.

Hypothesis 1 ‒ prevalence of negative feelings will be higher in females than males.

Hypothesis 2 ‒ prevalence of negative feelings will differ across age groups.

Procedure and participants

In total, 2634 participants (1536 females and 1098 males) aged 18 to 72 years (M=42.94, SD=13.13) were interviewed. National representative samples of Lithuanians were surveyed and analyzed, grouped into 18-29 years old group (N=496), 30-49 years group (N=1159), and 50-74 group (N=979). In each wave of survey different representative sample of Lithuania inhabitants was interviewed. During the time span of 70 days in lockdown, surveys were completed five times (each poll ending date March 30th, April 8th, April 30th, May 21st, June 8th) using computer- assisted web interviewing method were completed. Questions from Gallup’s Global Emotions Report were used to evaluate emotions, stress and pain: “Did you experience the following feelings most of the day yesterday? How about physical pain?”. Correspondingly questions about anxiety, sadness, stress, anger, enjoyment, calmness and physical pain were asked for evaluation. Demographic information of age, gender collected as well. Emotion states were explored and compared across five waves of surveying.

Data analysis procedure

We had two independent variables of gender (male, female) and three independent variables of age (18-29, 30-49, 50-74) based on demographic information provided by participants. There were seven dependent variables of self-reported emotions and states including anxiety, sadness, anger, enjoyment, calmness, stress, and physical pain. A between-subjects t-test was run on SPSS V.26 to compare male and female answers to each feeling question. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was used to compare three age groups on the same answers.

Stress

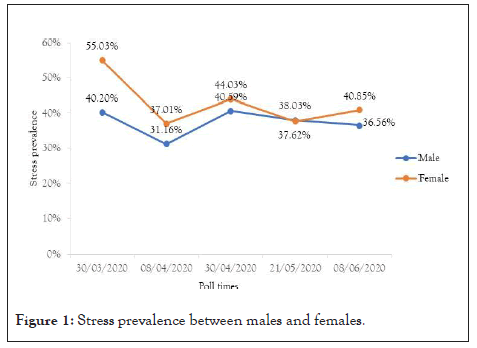

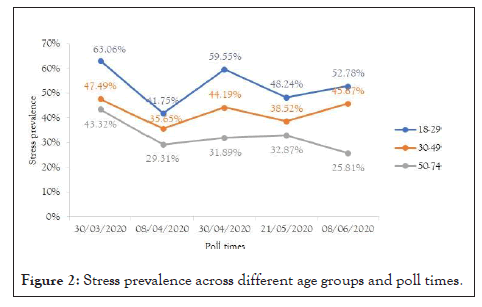

Across the five polls and all age groups, significantly more females (M=0.43, SD=0.495) than males (M=0.37, SD=0.484) expressed feeling stressed, t (2632)=-2.86, p<0.05. One-way ANOVA showed that stress differed statistically significantly between different age groups, F (2, 2631)=31.04, p<0.001. A Tukey HSD post hoc revealed that stress statistically decreased going upwards from the 18-29 age group (M=0.53, SD=0.499) to the 30-49 age group (M=0.42, SD=0.494) and to the 50-74 age group (M=0.32, SD=0.269), p<0.001 (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Stress prevalence between males and females.

Figure 2: Stress prevalence across different age groups and poll times.

Anxiety

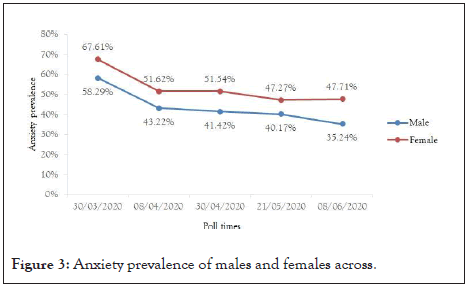

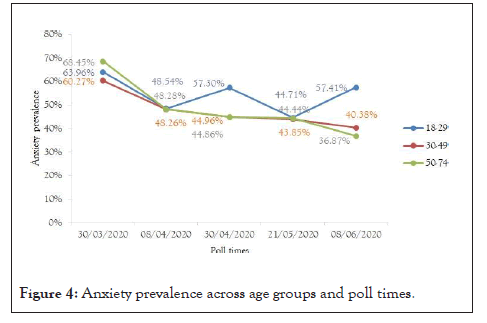

A similar trend was found on anxiety, as significantly more females (M=0.53, SD=0.49) than males (M=0.43, SD=0.496) reported feeling anxious, t (2632)=-5.08, p<0.001. One-way ANOVA revealed that anxiety differed statistically significantly between different age groups, F (2, 2631)=4.09, p<0.05. Anxiety rates were significantly higher in the 18-29 age group (M=0.55, SD=0.49) than in 30-49 (M=0.47, SD=0.50) and 50-74 (M=0.48, SD=0.50) groups, p<0.05. However, the differences between 30-49 and 50- 74 age groups were not statistically significant, p=0.951(Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3: Anxiety prevalence of males and females across.

Figure 4: Anxiety prevalence across age groups and poll times.

Sadness

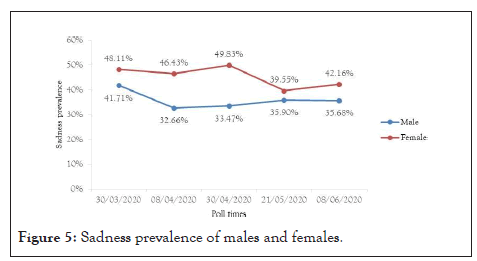

Once again females (M=0.45, SD=0.49) had significantly higher sadness rates than males (M=0.36, SD=0.43), t (2632)=-4.84, p<0.001.

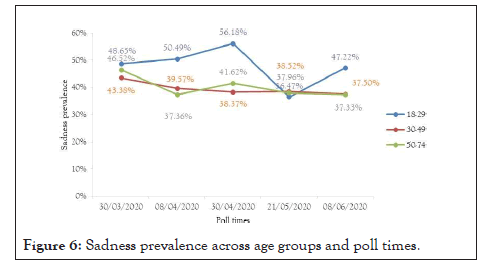

One-way ANOVA showed that sadness differed statistically significantly between different age groups, F (2, 2631)=5.75, p<0.01. The 18-29 age group (M=0.48, SD=0.50) had significantly highest sadness rates compared to the 30-49 age group (M=0.39, SD=0.49; p=0.003) and the 50-74 age group (M=0.40, SD=0.50; p=0.010). The differences between 30-49 and 50-74 age groups were not statistically significant p=0.956 (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5: Sadness prevalence of males and females.

Figure 6: Sadness prevalence across age groups and poll times.

Anger

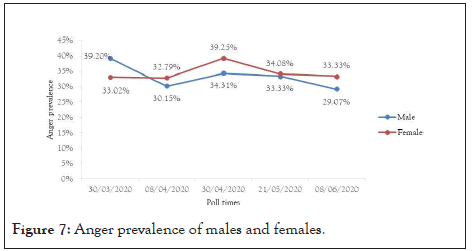

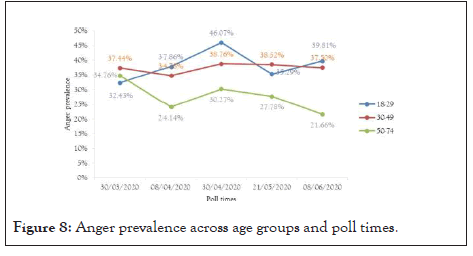

The prevalence of anger between females (M=0.34, SD=0.47) and males (M=0.33, SD=0.48) did not differ statistically significantly p=0.491. However, the anger scores of respondents of different ages varied significantly, F (2, 2631)=14.07, p<0.001. The 18- 29 age group (M=0.38, SD=0.49) had similar rates as 30-49 age group (M=0.37, SD=0.48) and both groups significantly differed from 50-74 group (M=0.32, SD=0.47, p<0.001) (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7: Anger prevalence of males and females.

Figure 8: Anger prevalence across age groups and poll times.

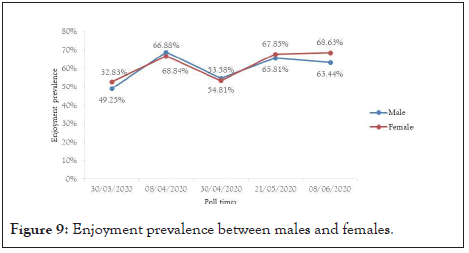

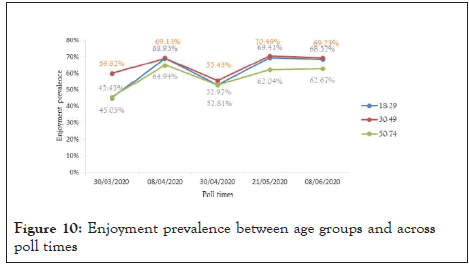

Enjoyment

No significant differences were found between males (M=0.60, SD=0.49) and females (M=0.62, SD=0.49) on enjoyment rates, t 2632)=-0.78, p=0.434. In age comparison emerged one significant (p=0.004) difference between 30-49 group (M=0.65, SD=0.48) and 50-74 group (M=0.58, SD=0.49). Effect of age was significant overall F (2, 2631)=5.26, p=0.005, despite 18-29 (M=0.61, 0.49) group showing no significant differences with other groups (Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 9: Enjoyment prevalence between males and females.

Figure 10: Enjoyment prevalence between age groups and across poll times

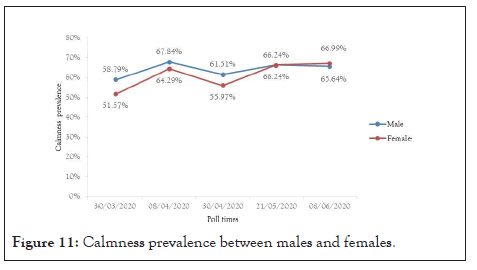

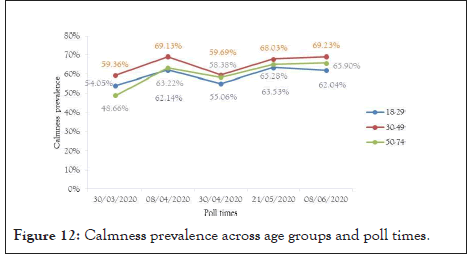

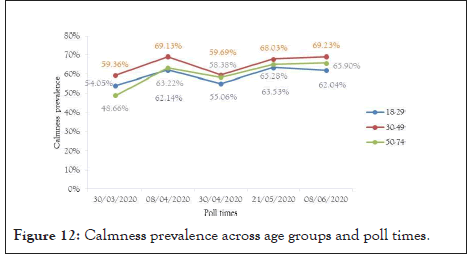

Calmness

No significant differences were found between males (M=0.64, SD=0.48) and females (M=0.61, SD=0.49) on calmness prevalence, t (2632)=1.58, p=0.114. One-way ANOVA showed a significant age effect on calmness prevalence F (2, 2631)=3.35, p=0.035, however post hoc test did not reveal between which groups it was. The averages for calmness prevalence are shown below (Figures 11 and 12).

Figure 11: Calmness prevalence between males and females.

Figure 12: Calmness prevalence across age groups and poll times.

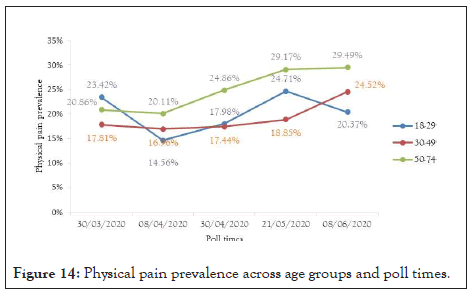

Physical pain

More females (M=0.23, SD=0.42) reported experiencing physical pain more than males (M=0.19, SD=0.39), t (2632)=-2.15, p=0.032.

Effect of age was significant F (2, 2631)=6.49, p=0.002 but only between 30-49 age group (M=0.19, SD=0.39) and 50-74 age group (M=0.25, SD=0.44). The 18-29 age group (M=0.20, SD=0.40) did not differ significantly from either group (Figures 13 and 14).

Figure 13: Physical pain prevalence between males and females.

Figure 14: Physical pain prevalence across age groups and poll times.

The present study hypothesized that females will show higher prevalence of negative feelings than males and that this prevalence will differ across age groups. First hypothesis had been partially supported as women reported higher prevalence than men on stress, anxiety, sadness, and physical pain. Anger prevalence difference between genders was not statistically significant. Second hypothesis was also supported as we found significant differences between certain age groups on stress, anxiety, sadness, and anger. For example, we found that stress gradually decreased with age and anxiety differed between youngest and oldest groups. Also, sadness was highest in youngest group while middle-aged and oldest did not differ significantly, and anger decreased with age as well. Additionally, we have found a trend on positive emotions as calmness and enjoyment increased for both genders and all age groups throughout the survey waves. A similar trend was found in the United States on positive impact of quarantine and it will be compared to our findings and discussion of possible explanations. To explain our findings on negative emotion trends, studies on gender differences and age in relation to mental health issues will be discussed.

Gender differences

We found that females reported higher prevalence of stress, anxiety, sadness, and physical pain than males over the course of our survey. Women also showed slightly more anger, but the effect was not statistically significant. A review by Albert supports our finding that females feel sadder and that they are two times more often diagnosed with depression than men. Anxiety disorder is also more often diagnosed for women as shown by [28] because females tend to internalize negative feelings more than males. A tendency of women to react more sensitively to stress than males was also found and explained [29]. And lastly, [30] found that women report up to 50% more physical symptoms than men, even after adjusting for psychiatric comorbidity. Although depression and anxiety strongly correlate with symptom reporting and such diagnoses are more frequent in women, physically unexplained (somatoform) symptoms were also more frequent in females. The trend of women experiencing negative feelings (stress, anxiety and sadness) more often than men can be explained by social gender roles and biological gender differences. Men and women are raised according to different social roles where men learn to be socially independent and solve problems themselves without relying too much on others [21] whereas women have more demanding social needs and seek out support from others more often than men do. This results in women reporting their issues and seeking help more often than men for mental health problems [31] Men experience negative emotions as well, but women tend to internalize their feelings rather than men who externalize and act them out. Our finding of females reporting overall more sadness, anxiety, and stress than men could be due to their gender role – being emotionally expressive, sensitive, and open about their feelings. It is also interesting how from the beginning of our survey, women’s anxiety rates were increasing with time, while that of men was gradually decreasing.

Differences in gender-related stress response can be due to differences in coping styles. Coping is the cognitive and behavioral response taken when faced with stressful situations or threats and is aimed at reducing distress. This can be avoidance or detachment and it can be problem-focused or emotion- oriented. Problem-focused coping includes cognitive and behavioral attempts to modify or eliminate the stressful situation, while emotion-oriented coping is aimed at changing emotional responses in the situation. Studies have suggested that the latter coping style is less effective and more associated with higher psychological distress [29]. There have also been found gender differences in coping styles in stressful situations. Matud has sampled over two thousand males and females to explore gender differences in stress prevalence, and in coping styles used. Various standardized questionnaires on stress were administered to differentiate how certain situations were more stressful for men or women. Women were found to more frequently use emotion- focused and avoidance coping than men who used rational and detachment style coping. Another explanation could be the biological (hormonal and neurological) differences between genders that result in female sensitivity to distress. A link has been found by Albert between female hormonal changes during menstrual milestones (puberty, pregnancy, menopause) and depression-related disorders (e.g. premenstrual or postpartum depression). Despite men carrying female hormones like estrogen themselves, without hormonal fluctuations, men are less susceptible to depression than women. Studies on hormonal contraceptives found some reduction of depression and anxiety rates compared to non-users, which supports the role of estrogen in such disorders [32]. Additionally, there have been neurological differences found as women appear to show a higher startle reflex in anticipation to threats than men [22]. Women’s EEG brain scans show higher startle potentiation to unpredictable threats than men, revealing their increased sensitivity to distress. Since COVID-19 pandemic was a real unpredicted physical threat, we found that women reacted more anxiously and reported more stress than men. As we have explained, it could be due to social upbringing differences and/or neurological trends.

Age differences

The participants aged 18-29 showed highest prevalence of stress, anxiety and sadness compared to other age groups. Anger was similarly more prevalent in the youngest and middle-aged group of 30-49 year-olds. The oldest group aged 50-74 had highest physical pain reports, but did not dominate on other emotions evaluated. An interesting trend was found in the 50-74 groups: initially they had the highest anxiety levels, but these rapidly diminished over the months of quarantine. Such trend could be explained by different life experiences and different ability to rationally cope with and adapt to threats such as COVID-19. We can speculate, that the oldest group has in their lifetime experienced a variety of social hardships and lived through different epidemic instances. This gives them the possibility to rationally evaluate threats and use more adaptive psychological strategies to deal with COVID-19. Thus, the oldest group, in spite of objectively being in a bigger danger, [3] paradoxically had experienced the least amount of stress and negative emotions.

Another explanation for differences between age groups in our study could be due to differences in age-related social needs. The 18-29 and 30-50 year-olds are more socially active and have bigger social networks than people of older age because social connections tend to shrink with time. Hence why the implied social isolation during quarantine possibly does bigger emotional harm to these groups by restricting their social activities. There could be more factors at play. One is disruption of habitual education and/or work processes. Chinese students reported high stress levels during COVID-19 lockdown as they had to adjust to remote lessons and exams. The middle aged, most economically active group had financial difficulties, as some lost their jobs or struggled to work remotely. During SARS outbreak, lowest household income predicted high stress and depression rates because people struggled to support their families [8]. Changed work routines can create tension and conflicts at home, limit financial freedom, and lead to future worries [8]. Thus it leads to more stress and anxiety for socially active and working people to be isolated at home than it does for people in retirement or nursing homes.

A study like ours was done in the US by the Gallup group to explore the emotional well-being of the general US population during national quarantine. They surveyed people from the end of March to the end of May using online polls and found similar trends to ours. Initial stress, worry, anger, and other feelings were prominent; especially females reported higher negativity than males, just las we have found. In their latest interview data taken April 27th-May 10th, 2020 more reports of happiness were found comparing to data from a month before [33]. No gender or age differences were reported for this finding, so similarly to ours it could be widespread across the whole population sample. Brenan did not interpret improved emotional states of respondents but did mention that the interviewing period was when stay-at-home orders were being lifted in some States and people began feeling happier, expecting that their isolation was coming to an end.

Findings in our study show increased calmness and enjoyment without social context that would raise expectations that quarantine will be lifted soon. This suggests other possible explanations. We speculate that changes in routine and decreased work stress by itself could have led to mood improvements for some people. Perhaps, working remotely from the comfort of home, and reduced work stress, allowed some people to improve their routine, sleep and eating habits and gave them a chance to balance their life. Some people might have enjoyed spending more time with their family, or having more time for themselves, which made their days more comfortable and enjoyable.

Our study has provided insight into how the general population of Lithuania was feeling during the 70 days period of the 92 day lockdown during COVID-19 pandemic. We have found gender differences in prevalence of negative emotions where women reported them more often than men. We also found how people of different ages reacted to the quarantine, revealing that the youngest participants felt the most distressed. These findings suggest that gender-specific and age-specific psychological and social assistance might be needed during pandemic.

This study, however, is subject to some limitations. Firstly, using a single question scale to measure emotions might lack validity. However, standardized multiple item questionnaires are hardly applicable in general population research because of their high cost and wide scope. Secondly, we were limited to the 70 day time span out of a longer 92 day quarantine period. The impact of COVID-19 is not over, and we might see different dynamics of emotions in months to come. Nonetheless, our findings provide an interesting picture about the dynamics of emotional reactions during quarantine in the general population and how they differ depending on gender and age. Our findings might provide useful insights for further psychological research and serve as an impulse to look for gender-specific and age-specific specific social and psychological support actions during pandemics.

Citation: Chomentauskas G, Dereskeviciute E, Kalanaviciute G, Alisauskiene R, Paulauskaite K (2021) The impact of quarantine on emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychol Psychother.11:390

Received: 04-Feb-2021 Accepted: 18-Feb-2021 Published: 25-Feb-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2161-0487.21.11.390

Copyright: © 2021 Chomentauskas G, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.