International Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation

Open Access

ISSN: 2329-9096

ISSN: 2329-9096

Research Article - (2021)Volume 9, Issue 3

Title: The relationship between lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide mortality rate: A systematic review.

Background: Suicide is one of the leading causes of death worldwide and is influenced by multiple factors. Recently, several studies have shown that lithium in drinking water is useful for reducing the suicide mortality rate. However, it is still uncertain whether lithium intake from drinking water can achieve an anti-suicidal effect. We performed a systematic review to determine the relationship between lithium in drinking water and suicide mortality rate.

Methods and Findings: We reviewed articles related to the lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide mortality rate in various geographical areas between 1990 and 2020. Of 17 articles in our systematic review, 13 reported that lithium in drinking water was significantly negatively associated with standardized mortality ratio (SMR), while 4

studies did not show any associations. On the other hand, others with meta-analysis indicated that there was a negative association between lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide mortality rate.

Conclusion: Most of the studies in this review revealed that lithium concentration in drinking water was inversely related to the expected suicide mortality rate in these studies. We reviewed these articles and maintain that the balance of lithium concentration in drinking water and SMR is important in determining whether lithium in drinking water

affects suicide mortality rate. If the lithium concentration is stable over the entire study region, or suicide mortality rate is very low, an association between the lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide mortality rate could not be detected even with high lithium concentrations. Therefore, it may be difficult to evaluate the effect of lithium

in drinking water on suicide. Further studies are needed to determine the factors related to suicide and lithium intake from sources other than drinking water to assess the relationship between tap water lithium concentration and suicide mortality rate.

Lithium in drinking water; Suicide; Mortality rate; Systematic review

According to a WHO report, suicide became a major problem and the second leading cause of death among 15- to 29-year- olds globally in 2016. Approximately 800,000 people die from attempted suicide every year. Suicide can also be called a worldwide phenomenon [1], because it occurs in all countries irrespective of income. It has a complex etiology and is influenced by sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, household income, unemployment rate, education, and history of childhood maltreatment [2–6]. Suicide can also be affected by genetic factors [7–9]. The novel coronavirus pandemic began in 2020 and spread worldwide without the prospect of immediate termination. In such a situation, rising suicide rates worldwide, including in Japan, raise concern.

Recently, it has been reported that lithium in drinking water may be a factor influencing suicide [10–13]. Lithium can be found naturally as a trace element in rocks and soil and can be dissolved in water. It has become one of the main treatments for mood and bipolar disorders. Lithium is mostly used in the form of lithium carbonate (Li2CO3) for the prevention and treatment of psychiatric disorders. The clinically recommended starting lithium carbonate dose for bipolar disorder is 400 mg/day, and 600 to 1200 mg/day (113–226 mg Li/day) is commonly used in clinical practice according to the American Psychiatric Association and Maudsley [14,15]. Many studies have also indicated that lithium can be effective in preventing homicide, addiction, and suicide [16,17].

Studies concerning the relationship between lithium concentrations in drinking water and the suicide mortality rate are contradictory. Some reports indicated that lithium in drinking water inhibited suicide [11–13], while others showed no relationship between the two [18–21]. Some disputes were highlighted in these studies. First, since the concentration of lithium in drinking water is very low compared to that used for the treatment purposes, it is doubtful if such a low concentration could influence suicide. The serum levels of lithium for therapeutic and prophylactic use for mood disorders are between 0.6 and 1.6 mmol/L [16], and between 0.6 and 0.75 mmol/L for long-term treatment of bipolar disorder [14]. However, one report indicated that the concentration of plasma lithium in 30 healthy people living in three regions of northern Chile was only 0.012 mmol/L [22]. This region is known to have one of the highest concentrations of lithium in drinking water. Second, the relationship between the serum level of lithium and the drinking water lithium concentration has not been made apparent in the literature.

The aim of this article was to review the literatures concerning the relationship between the concentration of lithium in drinking water and suicide. We evaluated (1) whether the small amount of lithium in drinking water reduces the suicide mortality rate even if there are many factors influencing suicide; and (2) what lithium concentration in drinking water is needed to affect suicide.

This article focused on the association between lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide mortality rate. We searched PubMed, Medline, Embase, and PsychLit for articles which analyzed this association. The main keywords for the search were lithium in the drinking water, suicide mortality rate. We collected and reviewed 17 studies (Table 1) related to the relationship between lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide from 1990 to 2020. Permission from the ethical review committee was not required since this study was a retrospective review. Informed consent was not required.

| Article | Country | Number of regions | Research year | Lithium concentration | Conclusion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean ± SD | ||||||

| Schrauzer et al. (1990) [11] | USA | 27countries in USA | 1978-1987 | 0-160 µg/L | - | T | Negative correlation |

| M | - | ||||||

| F | - | ||||||

| Ohgami et al. (2009) [12]# | Japan | 18 municipalities in Japan | 2002-2006 | 0.7-59 µg/L | - | T | Negative correlation |

| M | Negative correlation | ||||||

| F | No correlation | ||||||

| Kabacs et al. (2011) [18]# | England | 47 subdivision in England | 2006-2008 | 1-21 µg/L | - | T | No correlation |

| M | No correlation | ||||||

| F | No correlation | ||||||

| kapusta et al. (2011) [13]# | Austria | 99 districts in Austria | 2005-2009 | 3.3-82.3 µg/L | - | T | Negative correlation |

| M | Negative correlation | ||||||

| F | Negative correlation | ||||||

| Giotakos et al. (2013) [32] | Greece | 34 prefectures in Greece | 1999-2010 | 0.1-121 µg/L | 11.1 ± 21.16 µg/L | T | Negative correlation |

| M | - | ||||||

| F | - | ||||||

| Sugawara et al. (2013) [23]# |

Japan | 40 municipalities in Japan | 2010 | 0.0-12.9 µg/L | - | T | - |

| M | No correlation | ||||||

| F | Negative correlation | ||||||

| Blüml et al.(2013) [27] | USA | 226 countries in USA | 1999-2007 | 2.8-219.0 µg/L | - | T | Negative correlation |

| M | - | ||||||

| F | - | ||||||

| Pompili et al.(2015) [19]# | Italy | 145 sites in Italy | 1980-2011 | 0.11-60.8 µg/L | 5.28 ± 0.76 µg/L | T | No correlation |

| M | No correlation | ||||||

| F | No correlation | ||||||

| Ishii et al.(2015) [24]# | Japan | 274 municipalities in Japan | 2011 | 0-130 µg/L | 4.2 ± 9.3 µg/L | T | No correlation |

| M | Negative correlation | ||||||

| F | No correlation | ||||||

| Shiotsuki et al.(2016) [25]# |

Japan | 153 cities in Japan | 2010-2011 | 0.1-43 µg/L | 3.8 ± 5.3 µg/L | T | No correlation |

| M | Negative correlation | ||||||

| F | No correlation | ||||||

| Liaugaudaite et al. (2017) [29]# | Lithuania | 9 cities in Lithuania | 2009-2013 | 1.24-28.68 µg/L | 10.9 ± 9.1 µg/L | T | Negative correlation |

| M | Negative correlation | ||||||

| F | No correlation | ||||||

| Knudsen et al.(2017) [31] | Denmark | 151 areas in Denmark | 1991-2012 | 0.6-30.7 µg/L | 11.6 ± 6.8 µg/L | T | No correlation |

| M | - | ||||||

| F | - | ||||||

| Oliveria et al.(2019 ) [20]# | Portugal | 54 municipalities in Portugal | 2011-2016 | 1-191 µg/L | 10.9 ± 27.2 µg/L | T | No correlation |

| M | No correlation | ||||||

| F | No correlation | ||||||

| Palmer et al. (2019) [28]# | USA | 15 countries in USA | 1993-2013 | 0.1-60.6 µg/L | - | T | Negative correlation |

| M | Negative correlation | ||||||

| F | No correlation | ||||||

| Liaugaudaite et al. (2019) [30] |

Lithuania | 54 municipalities in Lithuania | 2012-2016 | 1-39 µg/L | 11.5 ± 9.9 µg/L | T | Negative correlation |

| M | No correlation | ||||||

| F | Negative correlation | ||||||

| Kozaka et al. (2020) [21]# | Japan | 26 municipalities in Japan | 2009-2013 | 0.2-12.3 µg/L | 2.8 ± 3.1 µg/L | T | No correlation |

| M | No correlation | ||||||

| F | No correlation | ||||||

| Kugimiya et al. (2020) [26]# | Japan | 808 regions in Japan | 2010-2016 | 0-43 µg/L | 2.39 ± 4.0 µg/L | T | Negative correlation |

| M | Negative correlation | ||||||

| F | No correlation | ||||||

Note: #: is used for Figure 1. T: Total (cumulative); M: Male; F: Female; -No data

Table 1: Characteristics of studies for systematic review

The details of the 17 studies are summarized in Table 1. There are six studies from Japan [12,21,23–26], three from the USA [11,27,28], two from Lithuania [29,30], one from Austria [13], and one each from Portugal [20], Denmark [31], England [18], Italy [19], and Greece [32].

The higher lithium concentration in drinking water did not reduce the suicide mortality rate in four articles. The findings of the remaining 13 studies showed a significant negative association between lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide mortality rate. However, some indicated a negative relationship only in the male population [12,24–26,28,29] and two study showed a significant negative relationship only in females [23,30].

Lithium concentration in drinking water ranged from 0 to 219 μg/L among studies showing a negative relationship, and 0.1 and 191 μg/L in those showing no relationship. The range of lithium concentration among studies with a negative relationship was wider than in those without any relationship, suggesting that the lithium concentration in drinking water could be an important factor influencing suicide. For example, Schrauzer and Shrestha reported that a significant negative relationship between lithium concentration in drinking water and suicides could be found only in countries with concentrations of lithium in drinking water of 70–170 μg/L [11]. In contrast, the groups with lithium levels of 70 μg/L or less did not show any significant association. Furthermore, a nationwide study in Japan recently revealed that, if the lithium level of drinking water was more than 30 μg/L, it could decrease the suicide rate [26].

Suicide has long been a severe global problem. There are many factors related to suicide. Unemployment rate, weather, age, income, and environmental conditions are thought to be factors. Several articles have reported that lithium in drinking water suppresses suicide [10–13]. However, reports of the relationship between lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide have been inconsistent. Therefore, we performed a systematic review of articles reporting this relationship. The first research on the concentration of lithium in drinking water and the suicide mortality rate was conducted by Schrauzer et al. in Texas [11]. They indicated a statistically significant difference in the suicide mortality rate in population groups defined according to mean water lithium levels (p< 0.005). The second report by Ohgami et al. showed the same relationship in Japan.

Lithium has been recommended as a useful drug for reducing the suicide mortality rate. Previous studies have reported that lithium treatment in patients with mood disorders was effective in reducing suicide risks [33–35]. The recommended lithium serum level for therapeutic and prophylactic use for mood disorders is between 0.6 and 1.6 mmol/L [16]. The American Psychiatric Association, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines also indicate that effective serum lithium level for the treatment of mood disorders should be maintained within 0.6–0.8 mmol/L [14,33]. Compared to these therapeutic serum levels, that of healthy individuals is low, 0.012 mmol/L according to one report [22]. It could be questioned that such low lithium concentrations suppress suicide.

We included 17 useful studies concerning the association between lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide mortality rates (Table 1). While there were more studies with significant negative relationships, it was difficult to decide whether negative relationships between lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide mortality rates were valid or not, because of negative publication bias. The meta-analysis indicated that lithium in drinking water was negatively associated with suicide mortality in the general population (OR=0.42) [36], and that males responded better to lithium than females [37,38].

Since there are many factors that influence suicide mortality rates, including socio-economic factors, gender differences, and genetic factors, Kozaka et al who was our colleague evaluated the association between the lithium concentration in drinking water and the suicide mortality rate in the Miyazaki prefecture in Japan [21]. A negative association between lithium in drinking water and suicide mortality rate was not detected, while there might be a relationship between rainfall, age, and suicide mortality rate. They also evaluated the relation between lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide mortality rate with some references, and assert that the balance of the suicide mortality rate and the range of the lithium concentration in drinking water are important in affecting SMR, and a suicide mortality rate of over 25.8/105 and a lithium concentration of 35.05 µg/L in drinking water was needed to detect if lithium concentration in drinking water could affect suicide mortality rate among male [21]. They concluded that a low lithium concentration and no regional differences were reasons why a negative relationship could not be found [21]. Kugiyama et al. indicated that if the lithium concentration in drinking water was over 30 μg/L, the suicide mortality rate might be lower [26].

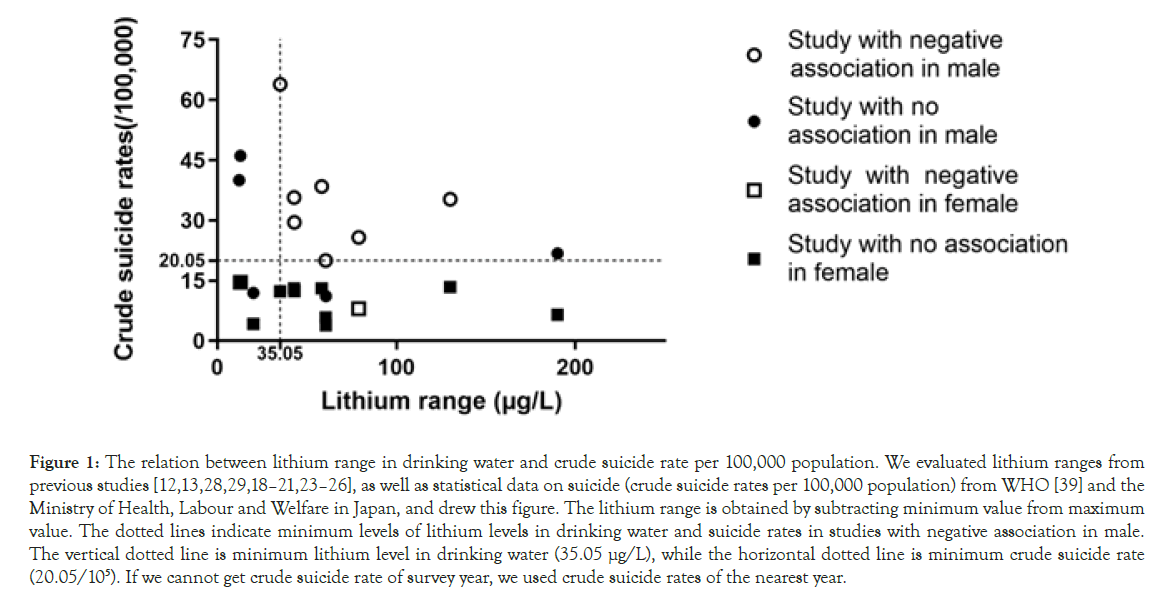

We reevaluate the relation among lithium concentration and suicide mortality rate with some references adding latest article (marked by # in Table 1) according previous study [21] and represented (Figure 1). The figure is similar to the previous report. And it indicated that a suicide mortality rate of over 20.05/105 and a lithium concentration of 35.05 µg/L in drinking water will be needed to detect if lithium concentration in drinking water could affect suicide mortality rate among male not female.

Figure 1: The relation between lithium range in drinking water and crude suicide rate per 100,000 population. We evaluated lithium ranges from previous studies [12,13,28,29,18–21,23–26], as well as statistical data on suicide (crude suicide rates per 100,000 population) from WHO [39] and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan, and drew this figure. The lithium range is obtained by subtracting minimum value from maximum value. The dotted lines indicate minimum levels of lithium levels in drinking water and suicide rates in studies with negative association in male. The vertical dotted line is minimum lithium level in drinking water (35.05 μg/L), while the horizontal dotted line is minimum crude suicide rate (20.05/105). If we cannot get crude suicide rate of survey year, we used crude suicide rates of the nearest year.

There are some limitations to studies concerning the relation between lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide mortality rate. Most of the articles in our review did not consider the daily intake of lithium from dietary sources. Grains, vegetables, dairy, fish, and meat naturally include lithium. Grains and vegetables are the main contributors to daily lithium intake, supplying 60% to over 90% of daily lithium requirements [40,41]. However, the dietary intake of lithium may be different in various regions and depends on the soil conditions, climate, and individual. Moreover, since the lithium in bottled water has been increasing in recent years [42], and we cannot ignore this source. It has also been pointed out that people with low serum lithium levels tended to be suicidal [10]. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the association between the lithium concentration in drinking water and the serum lithium level, or between serum lithium level and the suicide mortality rate in the healthy population.

Reports on the relationship between lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide mortality rate have been inconsistent. We indicated that the balance between the range of lithium concentration in drinking water and the suicide mortality rate could be important in detecting the effect of lithium concentration in drinking water on the suicide mortality rate. Since the intake of lithium comes not only from drinking water but also from foods and bottled mineral water, evaluating serum lithium level could be needed to assess the relationship between lithium concentration in drinking water and suicide. Therefore, further investigation concerning the relationship between lithium concentration in drinking water and serum lithium levels, as well as serum lithium levels and suicide will be necessary. We hope that our study will contribute to the research of future studies, and the results of this literature review can be utilized for beneficial purposes.

Not applicable.

There is no funding support for the conduct of this study.

There is no competing interest in this study.

Citation: Aung KZ, Hinoura T, Kozaka N, Kuroda Y (2021) The Relationship between Lithium Concentration in Drinking Water and Suicide Mortality: A Systematic Review. Int J Phys Med Rehabil. 9:593.

Received: 10-Feb-2021 Accepted: 24-Feb-2021 Published: 03-Mar-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2329-9096.21.9.593

Copyright: © 2021 Aung KZ, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.