Journal of Clinical & Experimental Dermatology Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-9554

ISSN: 2155-9554

Review Article - (2022)Volume 13, Issue 1

Managing the emotional impact of dermatological disorders in children with compulsive skin picking, trichotillomania, dermatitis artefacta, atopic dermatitis and pruritus is a particular challenge for dermatologists. Increased anxiety, low mood, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, as well as negative body image and low self-esteem are some of the difficulties reported in the literature. Their evaluation is usually difficult, especially in children who appear to be more sensitive and who have avoidant behavior. The Draw-A-Person test (D-A-P) seems to be a very helpful tool both in the evaluation of the above mentioned psychological difficulties, and in the identification of non-verbal behaviors that can occur during administration and also in the interpretation of its results. For this reason, it is suggested that the training and use of the test by dermatologists, who appear to be the first who come in contact with this sensitive population, can contribute to a better management of dermatological disorders, as well as to the referral of children to mental health professionals. This will result in a comprehensive interdisciplinary approach, leading to a more holistic clinical evaluation, aimed at improving the child's quality of life.

Draw-A-Person test (D-A-P); Psychological assessment; Psychodermatology; Non-verbal behavior

Several psychodiagnostic tests are used in the daily practice of clinical and educational psychologists in all European countries in order to assess intelligence, specific abilities or the emotional state of children and adolescents. Most of them are tools that are validated according to the norms of each population, while their administration requires a number of restrictions and procedures. Among clinical instruments, there is a category of tools, the projective tests, the use of which allows to omit several limitations which would make the therapeutic relationship difficult [1,2]. The projective drawing test (Draw-A-Person) was originally designed by Goodenough Florence [3] to evaluate children's cognitive capacity. Nowadays, in everyday clinical practice, it is used by psychologists as a projective test to detect adjustment difficulties, but also to investigate emotional difficulties [4]. The result of the children’s drawing activity is considered of rich diagnostic material and there is a clear system in the literature for the analysis and grading of the drawings.

However, every mental health professional usually administers the test based on their own hypotheses and diagnostic goals, while providing the child with a process that is often considered enjoyable, as it also enhances the psychotherapeutic process [5].

The Draw-A-Person test has several quantitative scoring systems suggested by psychologists [3,6-9]. Many of them analyze different aspects of the drawing, the presence or absence of specific body parts (head, clothing, and fingers), the proportion of body parts and the detail devoted to each one of them. In the dermatological practice we recommend its use as a tool for a smoother approach to the child, so as to verbalize their feelings and thoughts concerning their dermatological disorder, without the necessity of analyzing the drawing with strictly graded scoring systems. For this reason, the child's personal narrative and answers for their dermatological disorder is of more significant value, while dermatologists can more easily focus on observing the child's behavior and emotional state during the drawing process. The goal of the dermatologist using the Draw-A-Person test is to facilitate the start of the clinical interview with a very sensitive or withdrawn child, to create emotional contact and to create the motives for the completion of the drawing for a successful diagnostic procedure [10].

Draw-A-Person in dermatological practice

In the daily clinical practice of dermatologists, children with various dermatological disorders are evaluated, although their diagnosis needs an in depth evaluation. In cases of children with Dermatitis Artefacta (DA), Skin Picking Disorders (SPD), Trichotillomania (TTM), Atopic Dermatitis (AD) and pruritus, the clinical interview may present difficulties, especially since these children usually have high levels of anxiety, anger, shame [11,12], but also obsessive compulsive symptoms [13] with or without significant symptoms of dissociation [14-16]. Obtaining the necessary information can therefore be difficult if children do not feel comfortable in the dermatologist's office.

From a psychological perspective, identifying children's visible emotional difficulties (shame, withdrawal, and anxiety) reveals the need of the child to feel more comfortable. Based on this need, the dermatologist's encouragement to administer D-A-P test goes beyond the child's initial defense mechanism, while also bridging the emotional gap between the child and the adult who’s sitting opposite them [1,2,5].

At the first part of the test administration, the child's non-verbal and creative activity is clearly manifested. Initially, the classic guidelines for test administration are followed: The child is provided with a white piece of paper, a pencil and an eraser, while they can sit comfortably in a chair in front of a low desk [17]. Many researchers also have a variety of colored pencils or markers on display, without encouraging or asking the child to use them. During the administration, the child's parent ideally should sit behind the child, allowing the child to have eye contact only with their dermatologist. By focusing on the drawing, counseling and psychological correction techniques are limited by mental health professionals, while this method allows a wide range of psychological information to be obtained about the child being examined [1]. The idea of using the drawing of a person to identify emotional difficulties reduces the child’s level of anxiety and may intensify the verbal activity of the initially sensitive and withdrawned children [9].

Next, the instruction “please draw a person” is given. Regardless of the child’s chronological age, the instruction to draw a person causes almost no protest to any child. If the child asks for additional information, whether they should draw a boy or a girl, a small or a big drawing, then we give the instruction “just try to draw a person as best as you can”. In this way the child does not refuse to fulfill the instruction since it’s explained to them that the aim is not to assess their artistic ability. The drawing contains valuable data, while allowing us to obtain information about the cognitive level and personal characteristics of the child [7]. If the child gets angry, crosses his arms or behaves defensively, there is already enough information provided which reveals feelings of distrust and defense [18]. Most children, however, easily follow the instructions. If the child just draws a few lines, then the dermatologist should give them a new piece of paper and encourage them to draw a more complete person [9].

While the child is occupied with the drawing, the dermatologist observes and makes the appropriate entries in his observation sheet. Information listed may refer to the following: The child's emotional state, their attitude towards the process, the sequence of drawing elements and details, behaviors during the drawing (frequent erasure, pauses, corrections, rotation of the paper), spontaneous verbal and non-verbal reactions, increased focus or attention to specific parts of the person’s body and finally, the total time to complete the image [7].

In the suggested administration of the D-A-P test, when the child completes the drawing, the dermatologist takes the drawing and asks them to draw a person of the opposite sex [9]. In dermatological practice though, for reasons of saving time, but also for purposes of a smoother emotional comfort of young dermatological patients, if the child's first painting represents a person of the same sex, we do not proceed to ask them to draw a person of the opposite sex. If we want the child to draw directly themselves, then we directly give the instruction "draw me a picture of yourself". At this point the first administration part is completed.

The second part of administration is verbal and more structured [3,9]: The child is then given the opportunity to clarify and explain the content of the drawing, to express their associations that have arisen in relation to it. At that moment the dermatologist can consider that the subject illustrated is the self- portrait of the child [5,19]. Since the objects do not really have their own emotional coloring, the drawings reflect the subjective perception of the world and the self-perception of the child, while reflecting their emotional experiences [1,2,20]. With the dermatologist's encouragement a connection is created between the child's imaginary world and the right here-and-now difficulty arising from the dermatological disorder. Each special way of self-expression of the child is a reflection of their personal thoughts and feelings, so there are no right and wrong answers, as well as no right and wrong associations [7].

Subsequently, we ask the child to tell us a story about the person in the drawing, which would then be helpful to use in order to interpret how the dermatological disorder affects their life. Machover's classic questions for children can be used as a baseline for the beginning of the interview. Questions like “how old is the person drawn?”, “is he/she good looking?”, “what is the best/worst part of their body and why?”, “is he/she nervous?”, “what makes him/her happy or sad?”, “what gets him/her angry?”, “what are his/her habits?” and “what are his/her main wishes?”, are some examples that make it possible to assess the subjective importance of the child's values, needs and difficulties [9].

Particular attention in dermatological practice should be given to a selection of questions related to the skin condition, if children depict it in their drawing. Questions that may resemble the items of classic dermatological questionnaires (for example Skindex, NE-YBOCS, MIST-C or CDLQI) can be addressed by the dermatologist and relate to the person in the drawing and not the child itself. Some of these may include the following: “does their skin condition hurt?”, “does their skin condition affect how well they sleep?”, “does this person worry that their skin condition may be serious?”, “is this person ashamed/angry/ embarrassed/frustrated/annoyed by their skin condition?” [21,22]. Questions that evaluate children's body focused repetitive behaviors (i.e. trichotillomania, skin picking disorder) or obsessive compulsive symptoms may include the following: “does this person pull their own hair/pick their own skin?”, “how often do they do it?”, “is it hard for this person to stop hair pulling/skin picking?”, “how did this person feel after this behavior?" [23-26]. During these questions, dermatologists need to focus on the clinical examination of the child by observing if other repetitive behaviors are present (hair pulling, onychophagia, nose picking, lip biting or biting of the inside of the cheek). In the cases of children with body focused repetitive behaviors, the child channels through their behavior all information that concern their skin condition and what is not verbalized to their dermatologist. Also, some questions such as “does this person often hang out with boys/girls”, “when does he/she say he/she has a good time” and “how much has the skin condition affected the person in playing or doing hobbies” may indicate the impact of dermatological disorder on the social exposure or avoidance of children, but also their interpersonal sensitivity [27].

Necessary characteristics for observation during the test administration process

Regarding the level of psychomotor development of the child, we can obtain enough information from the speed and coordination of their movements. Based on the child’s fine motor skills, the pressure on the paper, the shading and the quality of the lines [18]. In case the child uses a marker or a paintbrush, the information we receive about the level of psychomotor development will be limited, as these materials do not allow the width of the lines and the pressure on the paper to be easily seen [3,9]. In addition, the analysis of the completeness and quality of the image allows us to form a quantitative assessment of the level of mental development of the child [3,7,8]. The correct use of additional colors in the drawing or the result of a drawing that suggests pre-existing knowledge obtained from extra curriculum classes also allows us to make assumptions about the education that may have been provided to the child or the socio-economic level of the family.

Regarding the emotional state of the child, it is possible to make assumptions, based on the analysis of the basic graphic features of the drawing [4]. The general assessment of the child's mood, as well as signs of emotional instability can be determined based on the analysis of the colors chosen, as well as the size of the person in the design (eg. darker colors, smaller human figures). Hypothesis about the childs’s personality traits can also be made through their drawing, such as devotion in more detail to specific parts of the body, indicating the child's attitude towards himself, but also how they interact with others [7]. The analysis of these points and their symbolic significance makes it possible to obtain valuable information. Additionally, assumptions about a child's level of adjustment can also be made based on their answers, so that personality traits that are maladaptive may emerge [9]. Color symbols may be related to the child's aesthetic preferences, while atypical color combinations may indicate personality traits such as imagination and creativity.

Indicative instructions on the interpretation of the results in dermatological practice with illustrative examples

Although the initial use of D-A-P test was to assess a child's cognitive age through the drawing, while assessing their visualmotor and cognitive skills, its individual use is considered unreliable across European countries if not administered along with a reliable and valid psychometric tool such as Wechsler Intelligence Test for Children [19,28]. For the test administration process by dermatologists, we suggest that it is better to be used for projective purposes, with the ultimate goal of a successful and smoother clinical interview, but also for the diagnosis of specific dermatological disorders in children. Therefore, the use of a scoring system such as that of Goodenough [3], or the systematic scoring system by Harris and Pinder [7], preferred by clinical psychologists and which includes a 73-point scale for male and a 71-point scale for female drawings, should be studied by dermatologists before administration, even if they will not proceed in a complete grading of the drawing. This will therefore provide the necessary knowledge for its use not as a psychometric tool, but as part of the clinical interview, during which the drawing and the children's answers concerning their dermatological disease will be interpreted along with all the information provided by the clinical observation [5].

As dermatologists observe the quality of the child's drawing, they can evaluate the following: The sequence of the drawing, the proportion of the spatial features of the design, as well as its entire size, reflects the realities of the child's life situation. However, projective diagnostic methods represent an example of a “strange discrepancy between theoretical research and practice”, so the concept of “projection” has many meanings [4,20], from the definition of the mechanism of psychological defense to the determination of the manifestation of the activity, the selectivity of the perception, mediated by internal conditions, the dermatologist's questions, the characteristics and the experience of the child. The process of interpreting a drawing is an attempt by the dermatologist to decipher its symbolic content.

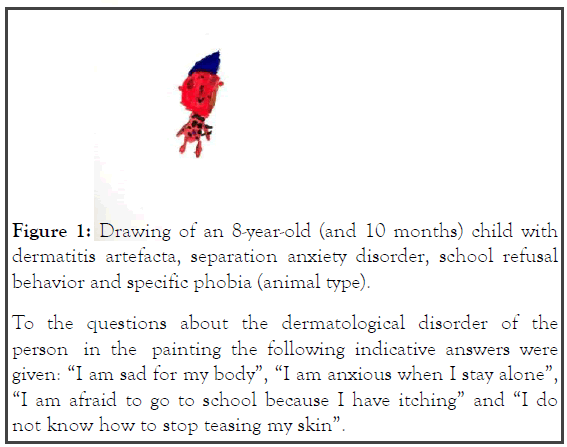

In cases where the child performs the drawing timidly and slowly, while seemingly concerned about the quality of the drawing, with the size of the person figure being too small, usually indicates low self-esteem and feelings of shame or embarrassment during the first part of the test [9,29]. These are usually accompanied by a low voice tone during the answers in the second part of the test [7]. If low voice tone and reduced eye contact accompany only the answers to the questions about the body part where the dermatological disorder is located, they may indicate reduced sense of attractiveness, but also feelings of anxiety, anger and helplessness regarding the inability to control the urge for scratching or rubbing of the skin area, which leads to the self-inflicted dermatological condition (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Drawing of an 8-year-old (and 10 months) child with

dermatitis artefacta, separation anxiety disorder, school refusal

behavior and specific phobia (animal type).

To the questions about the dermatological disorder of the

person in the painting the following indicative answers were given: “I am sad for my body”, “I am anxious when I stay alone”, “I am afraid to go to school because I have itching” and “I do

not know how to stop teasing my skin”.

In cases of children who are more extroverted and with higher self-esteem, the size of the person in the drawing is very large, while they perform the drawing much faster [4]. These children are usually continuously active on their chair, they do not seem to worry and they seem to be indifferent to the quality of their drawing [9]. In the second part of the test, they often respond with a happier style and a higher tone of voice, even if their answers provide information that confirms the dermatologist's initial assumptions about their negative emotions. All of this seem to change when the impact of dermatological disorder on their lives is investigated. Even a cheerful child may present nail or lip biting when asked the question “is it hard for this person to stop skin scratching?”. For this reason we should be prepared if we realize increased anxiety, anger or shame associated with the dermatological disorder, which in children may often be non- verbal, but presented behaviorally as withdrawal from activities they previously considered interesting and enjoyable (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Drawing of a 10-year-old (and 3 months) child with

atopic dermatitis, pruritus (itchy skin), ADHD and sleep disorder (parasomnia).

To the questions about the dermatological disorder of the

person in the painting the following indicative answers were

given: “I am angry and sad that I have this on my skin”, “I do

not want others to ask me why I constantly tease my armpits”, “at night I do not know if I am asleep, but sometimes I think I

wake up and it hurts” and “I stopped going to football because when I do, my skin burns afterwards”.

In cases where there is pressure of the pencil on the paper movements, while addressing questions about their performance. Encouragement often boosts their motivation, while the child's over-selective tendency for success is also revealed [9,20]. Children’s anxiety in these cases is manifested only behaviorally [13]. During the second part of the test, children often answer with a torrent of words, with a very detail-oriented speech. They encounter the drawing process very seriously and appear anxious about the result they have produced. They ask for details about the drawing they have painted and are interested in how the dermatologist or psychologist evaluates it. Throughout the answers concerning their dermatological disorder, their respond is very emotionally detached, revealing a strictly stereotypical way of thinking (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Drawing of a 12-year-old (and 4 months) child with

excoriation (skin-picking) disorder and prurigo, as a reaction after insect bite.

To the questions about the dermatological disorder of the

person in the painting the following indicative answers were given: “every day I am thinking that I have to tease my skin, but more often when I am bored”, “I feel very bad when others ask me what I have on my hands”, “for as long as I am teasing my skin I feel as if I am not there, as if I am observing myself from a distance” and “I want to stop teasing it but I do not know if I can”.

Dermatologists seem to be the first healthcare professionals to recognize the psychological impact of specific skin disorders on the emotional sphere of young patients. For this reason, psychological assessment of young patients with various skin conditions such as dermatitis artefacta, compulsive skin picking, trichotillomania, atopic dermatitis and pruritus might be challenging. The use of D-A-P test seems to be the proper tool for dermatologists to approach young and sensitive children non-verbally, in order to obtain the necessary information for a more accurate diagnosis. Children’s answers on their drawing through the clinical interview, allow the dermatologist to assess the impact of skin disorders on the emotional, family and social life of the child, in a very short time. Early detection of emotional difficulties by the dermatologist and referral to a clinical psychologist could benefit the child, as the pharmacological approach could be enhanced through additional screening psychometric tests and psychotherapeutic sessions.

All children's drawings have been used with the written permission of their parents. The D-A-P test was administered by the researcher who is a registered clinical psychologist and all psychological diagnoses were based on the DSM-V criteria. The diagnoses of all skin conditions were exclusively performed by dermatologists.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

No funding.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

Citation: Costeris C (2022) The Use of Draw-A-Person Test in Psychodermatology: How to Evaluate Children with Skin Conditions who Experience Emotional Difficulties. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 13:593.

Received: 04-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. JCEDR-22-15431; Editor assigned: 07-Mar-2022, Pre QC No. JCEDR-22-15431 (PQ); Reviewed: 18-Mar-2022, QC No. JCEDR-22-15431; Revised: 24-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. JCEDR-22-15431(R); Published: 28-Mar-2022 , DOI: 10.35248 /2155-9554.22.13.59

Copyright: © 2022 Costeris C. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.