Journal of Sleep Disorders & Therapy

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0277

ISSN: 2167-0277

Research Article - (2021)Volume 10, Issue 3

Objectives: To compare whether nonapnea sleep disorders (NASDs) or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)are associated with an increased risk of obesity.

Methods: From January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2015, we identified 24 363 patients with obesity from the 2005 Longitudinal Health Insurance Database, which is part of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database; 97 452 patients without obesity were also identified from the same database. The age, sex, and index date were matched. Multiple logistic regression was used to analyze the previous exposure risk of patients with obesity and NASD or OSA. A P value of <.05 was considered significant.

Results: Patients with obesity were more likely to be exposed to OSA than did those with NASD (OSA adjusted OR [AOR] = 2.927, 95% CI=1.878-4.194, P < .001; NASD adjusted OR [AOR]=1.693, 95% CI=1.575-1.821, P< .001). Furthermore, the closeness of the exposure period to the index time was positively associated with the severity of obesity, with a dose– response effect (OSA exposure <1 year, AOR=3.895; OSA exposure ≥ 1 year and <5 years, AOR=2.933; OSA exposure ≥5 years, AOR=2.486 ; NASD exposure <1 year, AOR=2.386; NASD exposure ≥1 year and <5 years, AOR=1.725; NASD exposure ≥5 years, AOR=1.422). The exposure duration of OSA in patients with obesity was 2.927 times than that of NASD was 1.693 times. Longer exposure durations were associated with more severe obesity with a dose–response effect (OSA exposure <1 year, AOR = 2.251; OSA exposure ≥1 year and <5 years, AOR=2.986; OSA exposure ≥5 years, AOR=3.452; NASD exposure <1 year, AOR=1.420; NASD exposure ≥1 year and <5 years, AOR=2.240; NASD exposure ≥5 years, AOR=2.863).

Conclusions: The risk of obesity was determined to be significantly higher in patients with OSA than that of NASD in this nested case-control study. Longer exposure to OSA or NASD was associated with a higher likelihood of obesity, with a dose-response effect.

Nonapnea Sleep Disorder; Obstructive Sleep Apnea; Obesity; National Health Insurance Research Database; Nested Case-Control Study

The World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that “obesity is a chronic disease” and highlighted the health hazards of obesity. Obesity may gradually cause or aggravate various complications, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease (CVD), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, reproductive dysfunction, abnormal breathing, and mental illness, and even increase the risk of certain types of cancer depending on the degree, duration, and distribution of excess body weight and fat tissue [1]. In the latest survey, the National Health Administration of the Ministry of Health and Welfare reported that the rate of obesity among adults (≥18 years of age) has increased from 38% in 2009 to 43.9% in 2018 [2]. Compared with people with a healthy weight, obese people have more than 3 times the risk of diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and dyslipidemia and 2 times the risk of hypertension, CVD, knee arthritis, and gout.

According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2014), SDs are divided into 7 categories: insomnia, sleep-related breathing disorders, central disorders of hypersomnolence, circadian rhythm SDs, parasomnias, sleep-related movement disorders, and other SDs [3]. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is classified as a sleep-related respiratory system disease and is divided into two categories (adult OSA and pediatric OSA) in the third edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3) [4]. The difference between OSA and central sleep apnea (CSA) is that CSA is characterized by reduced or stopped breathing due to reduced effort rather than an upper airway obstruction [5]. It is necessary to evaluate respiration to correctly classify apnea as obstructive, considering the specificity of muscle activity in the absence of airflow and whether respiration continues or increases [6-7]. Nonapnea SD (NASD) refers to SDs other than sleep apnea. Studies have extensively studied the association between SDs and chronic diseases. NASD has recently been associated with an increased risk of other comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic kidney disease (CKD), CVD, and stroke [8-11]. However, the relationship between SDs and obesity may be a critical mediating factor linking SDs with chronic diseases, including CVD and DM, in all age groups [12,13]. Understanding this connection may help in developing effective therapeutic interventions for SDs and obesity [14,15]. Longitudinal observational studies investigating the relationship between SDs and obesity are limited. Therefore, we hypothesized that OSA or NASD is related to obesity. We used the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of the Ministry of Health and Welfare to investigate whether OSA or NASD increases the subsequent risk of obesity.

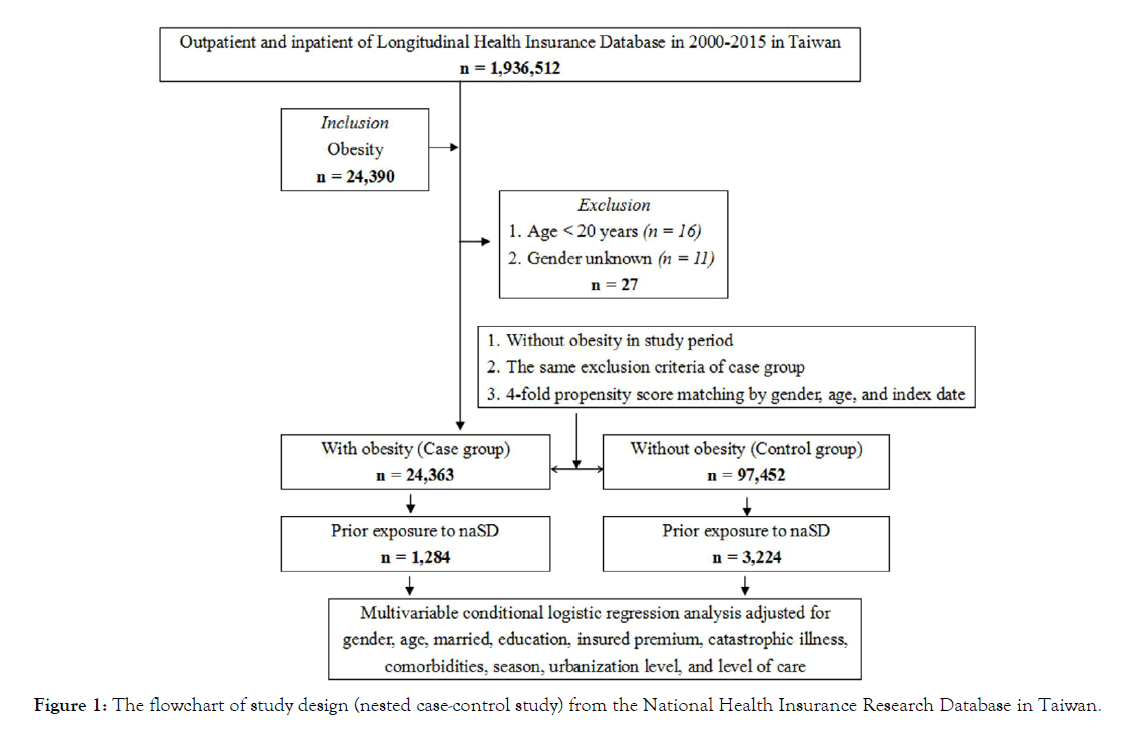

Data source: Taiwan’s National Health Insurance launched the single-payer system on March 1, 1995. As of 2017, 99.9% of Taiwan’s population is enrolled in this program. Data for this study were collected from the 2005 Longitudinal Health Insurance Database (LHID2005), which is part of the NHIRD, and 2 000 000 people were randomly selected from the entire population. The National Institutes of Health encrypts all personal information before releasing the LHID2005 to protect the privacy of patients. In the LHID2005, the disease diagnosis code is based on the “International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification” (ICD-9-CM) criteria [16]. The flowchart of study design (nested case-control study) from the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan (Figure 1). All methods were carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects or if subjects are under 18, from a parent and/or legal guardian. The Ethical Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital of the National Defense Medical Center (TSGHIRB No. B-109-39) approved this study.

Figure 1: The flowchart of study design (nested case-control study) from the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan.

Determining cases and controls

Patients diagnosed as having obesity (ICD-9-CM code 178) were defined as an obesity case group. The control group consisted of patients without obesity. Patients in both the case and control groups were matched by the index date, sex, and age at a ratio of 4:1.

Identifying SDs, obesity, and comorbidities

The risk factor discussed in this study is SD, which is defined based on at least 3 outpatient diagnoses from 2000 to 2015, identified using the ICD-9 codes 780.5 (SDs); 780.50 (SDs, not specified); 780.52 (insomnia, not specified); 780.51, 780.53, and 780.57 (sleep apnea syndrome); 307.4 (specific SDs of nonorganic origin); 780.54 (insufficient sleep, unspecified); 780.55 (24-hour sleepwake cycle interruption, unspecified); 780.56 (dysfunction related to the sleep phase or awakening from sleep); 780.58 (dyskinesia related to sleep, unspecified); and 780.59 (SDs, other).

The outcome of obesity was measured in patients diagnosed as having the following conditions: overweight, obesity, and other hyper alimentation (ICD-9-CM code 278); overweight and obesity (ICD-9 CM code 278.0); morbid obesity (ICD-9-CM code 278.01); overweight (ICD-9-CM code 278.02); and obesity hypoventilation syndrome (ICD-9-CM code 278.03).

The comorbidities evaluated in this study were DM (ICD-9-CM code 250), hypertension (ICD-9-CM code 401-405), hyperlipidemia (ICD-9-CM code 272.4), CAD (ICD-9-CM code 414.01), stroke (ICD-9-CM code 430-438), chronic heart failure (ICD-9-CM code 428.0), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ICD-9-CM code 490-496), CKD (ICD-9-CM code 585), liver cirrhosis (ICD-9-CM code 571.5), tumor (ICD-9-CM code 199), anxiety (ICD-9-CM code 300.00), and depression (ICD-9-CM codes 296.2-296.3, 300.4, and 311).

Statistical analysis: Descriptive data are presented as percentages, means, and standard deviations. The chi-square test and t test were used to evaluate the distribution of categorical and continuous variables between cases and controls. Conditional logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of OSA or NASD on the risk of obesity after adjusting for age, sex, education, insured premium, comorbidities, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), season, location, urbanization level, and level of care. The effect of the first to last OSA or NASD exposure before obesity diagnosis on the factors of obesity was examined using conditional logistic regression. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Demographic data: As presented in (Table 1), the average age of 121815 patients was 44.30 ± 15.64 years, among whom 42.77% were men and 57.23% were women. We recruited 24 363 patients with obesity (cases) and 97 452 patients without obesity (controls). Patients in the case group had a higher prevalence of comorbidities than did those in the control group. In the case group, the CCI and season were significant.

| Obesity | Total | Cases | Controls | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n % | n % | n % | |||||

| Total | 121815 | 24363 20.00 | 97452 80.00 | <.001 | ||||

| OSA Without |

119280 97.92 | 22572 92.65 | 96708 99.24 | |||||

| With | 2535 2.08 | 1791 7.35 | 74 0.76 | |||||

| NASD | ||||||||

| Without | 117307 96.30 | 23079 94.73 | 94228 96.69 | |||||

| With | 4508 3.70 | 1284 5.27 | 3224 3.31 | |||||

| Sex | .999 | |||||||

| Male | 52105 42.77 | 10421 42.77 | 41684 42.77 | |||||

| Female | 69710 57.23 | 13942 57.23 | 55768 57.23 | |||||

| Age (years) | 44.30 ± 15.64 | 44.25 ± 15.53 | 44.31 ± 15.67 | .592 | ||||

| Age group (yrs) | .999 | |||||||

| 20-44 45-64 ≥65 |

74135 47.48 34330 21.99 47680 30.54 |

14827 47.48 6866 21.99 9536 30.54 |

59308 47.48 27464 21.99 38144 30.54 |

|||||

| Married | ||||||||

| OSA Without |

55,634 45.67 | 11,375 46.69 | 44,259 45.42 | <.001 <.001 |

||||

| With NASD |

66,181 54.33 | 12,988 53.31 | 53,193 54.58 | |||||

| Without With |

55599 45.64 66216 54.36 |

11298 46.37 13065 53.63 |

44301 45.46 53151 54.54 |

|||||

| Comorbidities <.001 | ||||||||

| CCI_R OSA 0.05 ±0.29 0.07 ± 0.38 0.05 ± 0.26 <0.001 NASD 0.04 ± 0.35 0.05 ± 0.3 0.04 ± 0.35 <.001 |

||||||||

| Season OSA |

<0.001 <0.001 |

|||||||

| Spring (Mar-May) | 28,626 23.50 | 6,110 25.08 | 22,516 23.10 | |||||

| Summer(Jun-Aug) | 31,018 25.46 | 6,646 27.28 | 24,372 25.01 | |||||

| Autumn(Sep-Nov) | 33,587 27.57 | 6,201 25.45 | 27,386 28.10 | |||||

| Winter (Dec-Feb) | 28,584 23.47 | 5,406 22.19 | 23,178 23.78 | |||||

| NASD Spring (Mar-May) | 28696 23.56 | 6246 25.64 | 22450 23.04 | |||||

| Summer(Jun-Aug) | 30814 25.30 | 6513 26.73 | 24301 24.94 | |||||

| Autumn(Sep-Nov) | 32794 26.92 | 6029 24.75 | 26765 27.46 | |||||

| Winter (Dec-Feb) | 29511 24.23 | 5575 22.88 | 23936 24.56 | |||||

P: Chi-square/Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables.

Table 1: Characteristics of patients.

P: Chi-square/Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables.

Logistic regression of obesity variables as shown in (Table 2), a significantly higher risk of obesity was observed in the OSA group than in the control group (AOR=2.927, 95% CI=1.878- 4.194), NASD group than in the control group (AOR=1.693, 95% CI=1.575-1.821). Men (OSA) had 0.759 times the risk of obesity than did women (OSA) (AOR=0.759, 95% CI=0.735- 0.783), Men(NASD) had 0.810 times the risk of obesity than did women(NASD) (AOR=0.810, 95% CI=0.785-0.865).

| Variables | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| OSA Without |

Reference | ||

| With NASD |

2.927 | 1.878-4.194 | <.001 |

| Without | Reference | ||

| With | 1.693 | 1.575-1.821 | <.001 |

OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; Adjusted OR: Adjusted odds ratio

Table 2: Logistic regression of obesity variables.

Logistic regression to stratify the obesity factors of the listed variables as presented in (Table 3), the risk of obesity was higher in patients with OSA than with NASD (AOR = 2.927 V.S. 1.693).

| Group | AOR | With SD vs. without SD | (Reference) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stratified | OSA | NASD | P Value | |

| Total | 2.927(1.878–4.194) | 1.693 (1.575-1.821) | <.001 | |

Adjusted OR = Adjusted odds ratio (adjusted for the variables listed in Table 3); CI = confidence interval

Table 3: Factors of obesity stratified by variables using logistic regression.

Logistic regression to analyze obesity factors between different periods of nonapnea sleep disorder exposure As illustrated in (Table 4.1), obese patients were more likely to have experienced OSA compared with nonobese patients (AOR=2.927). Obese patients were more likely to have experienced NASD compared with nonobese patients (AOR=1.693) Furthermore, the closeness of the exposure duration to the time of the study was positively associated with obesity severity in a dose–response manner (OSA exposure < 1 year, AOR = 3.895; OSA exposure ≥ 1 year and <5 years, AOR=2.933; OSA exposure ≥ 5 years, AOR=2.486, NASD exposure < 1 year, AOR = 2.386; NASD exposure ≥ 1 year and <5 years, AOR=1.725; NASD exposure ≥ 5 years, AOR = 1.422). Furthermore, (Table 4.2) reveals that the mean exposure duration of OSA in patients with obesity was 2.927 times that in patients without obesity (AOR =2.927). The mean exposure duration of NASD in patients with obesity was 1.693 times that in patients without obesity (AOR=1.693). Third, a longer exposure duration was associated with more severe obesity, with a dose–response effect (OSA exposure <1 year, AOR=2.251; OSA exposure ≥ 1 year to <5 years, AOR=2.986; OSA exposure ≥ 5 years, AOR=3.452. NASD exposure <1 year, AOR=1.420; NASD exposure ≥ 1 year to < 5 years, AOR = 2.240; NASD exposure ≥ 5 years, AOR=2.863)

| The first SD exposure to the last one before obesity diagnosis | AOR With SD vs. without SD(Reference) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OSA | NASD | P Value | |

| Overall | 2.927 | 1.693 | <.001 |

| <1 year | 3.895 | 2.386 | <.001 |

| ≥ 1 year, <5 years | 2.933 | 1.725 | <.001 |

| ≥ 5 years | 2.486 | 1.422 | <.001 |

AOR = Adjusted odds ratio (adjusted for variables listed in Table 4.1)

Table 4.1: Factors of obesity among different SD exposure periods by using conditional logistic regression.

| Obesity diagnosis from different durations of SD exposure | AOR With SD vs. without SD | (Reference) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OSA | NASD | P Value | |

| Overall | 2.927 | 1.693 | <.001 |

| <1 year | 2.251 | 1.420 | <.001 |

| ≥1 year, <5 years | 2.986 | 2.240 | <.001 |

| ≥5 years | 3.452 | 2.863 | <.001 |

AOR = Adjusted odds ratio (adjusted for variables listed in Table 4.2)

Table 4.2: Factors of obesity from different durations of SD exposure by using conditional logistic regression.

This study aims to compare whether NASD or OSA is associated with an increased risk of obesity. To our research, this study may be the first study to compare whether NASD or OSA is associated with an increased risk of obesity. The results of this study found that the risk of OSA with obesity was significantly greater than NASD with obesity (AOR = 2.927 VS 1.693), especially if obese patients were previously exposed to the two types of sleep disorders is 2.927 and 1.693 times that of non-obese patients, and the closer the exposure duration is to the current time, the more serious the obesity situation. The relationship between obesity and the two types of sleep disorders shows a dose-response (Dose-Response); besides, the probability of obesity exposure duration of the two types of sleep disorders is 2.927 and 1.693 times that of non-obese patients, and the longer the exposure duration, the more serious the obesity situation, and the relationship between obesity and the exposure duration of the two types sleep disorders also show a dose-effect (Dose-Response effect).

Recent studies have shown that OSA may lead to obesity and weight loss leads to improvements in OSA [17]. If sleep disorders appear to be a risk factor for obesity, split sleep, overall sleep loss, and daytime sleepiness associated with OSA may also contribute to obesity, thereby further worsening OSA [18]. Sleep loss is not only due to habitual behavior, but also pathological conditions related to sleep disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). The increase in the prevalence and severity of obesity has led to an increase in the prevalence of obesity-related comorbidities, including OSA [19]. According to this new paradigm, OSA will lead to a complex interaction of behavioral changes, leptin resistance and increased ghrelin levels, leading to reduced physical activity and/or increased unhealthy eating habits [20]. It is estimated that the prevalence of OSA in the U.S. adult population is 24% and that of women is 9%, but the prevalence of severe obesity is as high as 93.6% in men and 73.5% in women. 20 Our research shows that OSA is associated with an increased risk of obesity.

The mechanism of non-apnea sleep disorder (NASD) affecting overall health is unclear, but some studies have shown that sleep changes may affect the levels of various inflammatory markers, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), C-reactive protein (CRP)) and regulate the intermittent response of inflammation. [21-23] severe obesity seems to be related to obvious sleep disturbances, even in individuals with NASD. [24-25] this kind of sleep disorder may also cause severely obese people to accumulate sleep debts and may lead to an appetite unregulated, restrict physical activity, and further impair weight maintenance. [26] these pathophysiological factors may explain the association between NASD and obesity demonstrated in this study. Our research shows that NASD is associated with an increased risk of obesity.

Our results show that the OSA risk of obesity is significantly higher than that of obese NASD, and the closer the exposure duration is to the present time, the more serious the obesity situation; the probability of exposure duration of the two sleep disorders in obese patients is 2.927 and that of non-obese patients. 1.693 times, and the longer the exposure time, the more serious the obesity situation. Therefore, the relationship between the occurrence and duration of OSA or NASD and obesity warrants consideration.

This study has several limitations. First, the NHIRD does not provide detailed information, such as that related to alcohol consumption, smoking, eating, and physical activity behaviors, which may affect our findings. Second, the Body Mass Index (BMI) was not a variable in our study. Third, although this study was carefully designed and controlled for confounding factors, biases may still exist because of unmeasured or unknown confounding factors (eg, the onset of anxiety, the stage of obesity at the time of diagnosis, and drugs that may affect the outcome). A prospective cohort study is recommended to evaluate the relationship between OSA or NASD and obesity.

The results of this nested case-control study revealed that patients with obesity experienced more severe OSA than did those with NASD. Furthermore, the closeness to the time of the study and the exposure duration were both positively related to the severity of obesity, with a dose-response effect. OSA or NASD may be a risk factor for obesity. Health care providers should pay close attention to the association between OSA or NASD and the risk of obesity.

This study was supported by Tri-Service General Hospital Foundation, grant number TSGH-B-110012. We wish to thank Taiwan’s Health and Welfare Data Science Center and the Ministry of Health and Welfare (HWDC, MOHW) for providing the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD).

Not applicable

Conceptualization: Hsiu-Chen Tai , Wu-Chien Chieni, Shi-Hao Huang, Yao-Ching Huang

Formal analysis: Hsiu-Chen Tai, Chien-An Sun; Nian-Sheng Tzeng, Wu-Chien Chien

Investigation: Chi-Hsiang Chung, Chien-An Sun

Methodology: Wu-Chien Chien, Chi-Hsiang Chung, Chien-An Sun

Project administration: Wu-Chien Chien, Chi-Hsiang Chung

Writing – original draft: Hsiu-Chen Tai, Shi-Hao Huang, Yao- Ching Huang

Writing – review & editing: Wu-Chien Chien, Chien-An Sun

Data are available from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) published by the Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) Administration. Due to legal restrictions imposed by the government of Taiwan concerning the “Personal Information Protection Act,” data cannot be made publicly available. Requests for data can be sent as a formal proposal to the NHIRD (http://www.mohw.gov.tw).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tri- Service General Hospital at the National Defense Medical Center in Taipei, Taiwan (TSGH IRB No.B-109-39). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects or, if subjects are under 18, from a parent and/or legal guardian.

Not applicable

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Citation: Tai HC, Huang SH, Huang YC, Chung CH, Sun CA (2021) This Nested Case-Control Study Revealed That Patients with Obesity Experienced More Severe OSA than did those with NASD. J Sleep Disord Ther 10:327.

Received: 03-Mar-2021 Accepted: 15-Mar-2021 Published: 22-Mar-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2167-0277.21.10.327

Copyright: © 2021 Tai HC, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.