Journal of Clinical & Experimental Dermatology Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-9554

ISSN: 2155-9554

Case Report - (2019)Volume 10, Issue 1

Keratosis Lichenoides Chronica (KLC) is a rare and chronic disorder of keratinization of unknown etiology. It is a progressive disease characterized by the linear and reticulate appearance of erythematous-to-violaceous keratotic and lichenoid papules over the trunk and limbs. KLC is uncommon in the pediatric population is uncommon and its clinical and histopathological presentation differs from the adult form. We report two cases in pediatric population, one of which has been treated successfully by acitretin. We also review the clinical and histopathologic features of the pediatric versus the adult form.

Keratosis lichenoides chronica; Dermatopathology; Inflammatory disorders

Keratosis Lichenoides Chronica (KLC), also known as Nekam’s disease, is a rare and chronic disorder of keratinization of unknown etiology [1,2]. It is a progressive disease characterized by the linear and reticulate appearance of erythematous-to-violaceous keratotic and lichenoid papules over the trunk and limbs and a seborrheic-like dermatitis over the face [2,3]. The course of KLC is chronic and resistant to therapy [2]. It presents mainly in adults between 20 and 40 years of age [4]. It is uncommon in the pediatric population. We report two case of KLC and compare the clinical and histopathologic features of pediatric and adult forms.

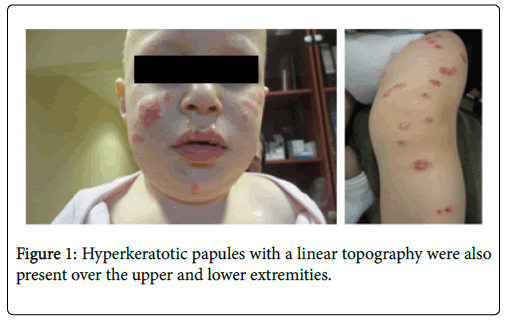

An 18-month-old, Lebanese male patient, with a non-remarkable personal and family history presented for evaluation of chronic, pruritic Lesions involving the face, as well as the upper and lower extremities. The lesions appeared at the age of 3 months. Topical corticosteroid and antibiotic ointments had been used with no improvement. Oral antibiotics were also prescribed with no improvement. Physical examination revealed the presence of erythemato-squamous annular plaques over the face, trunk, and limbs. Hyperkeratotic papules with a linear topography were also present over the upper and lower extremities (Figure 1). No scalp, ungual, oral, or genital involvement was noted. Lesions improved with sun exposure. Autoantibodies were negative.

Figure 1: Hyperkeratotic papules with a linear topography were also

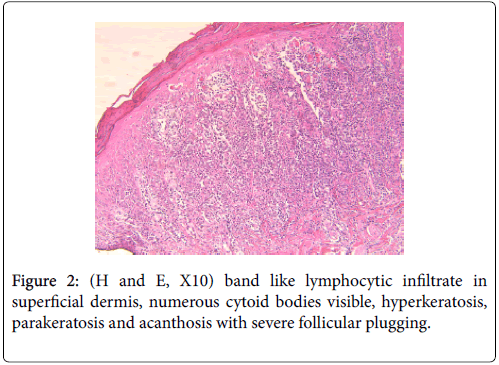

Two punch biopsy specimens from different lesions were taken for histopathologic evaluation. Findings were similar in all specimens. A band like lymphocytic infiltrate in superficial dermis, with occasional plasma cells and melanophages associated with hydropic degeneration of the dermoepidermal junction, leaving numerous cytoid bodies visible. The epidermis showed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis and acanthosis with severe follicular plugging (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative. The diagnosis of KLC was retained. Patient was started on topical tacrolimus and lost to follow-up.

Figure 2: (H and E, X10) band like lymphocytic infiltrate in superficial dermis, numerous cytoid bodies visible, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis and acanthosis with severe follicular plugging.

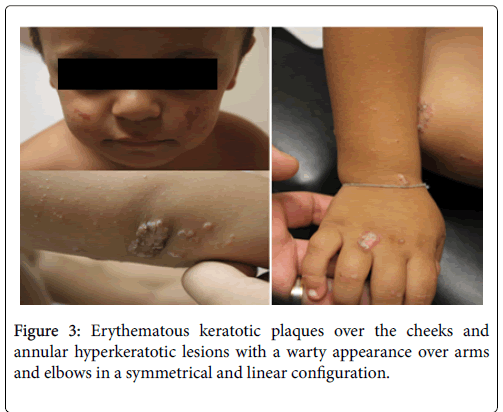

A 2-year-old, Lebanese male patient, born from consanguineous parents presented for evaluation of chronic non-pruritic lesions affecting the face and upper extremities. Family reports appearance of scaly erythematous lesion over bilateral cheeks at the age of 4 months with non-conclusive biopsy done previously. He was treated using potent steroids and hydrating creams with no improvement although improvement was noted in summer season. At the age of 9 months, additional lesions appeared over arm, elbows and knees. Physical examination revealed the presence of erythematous keratotic plaques over the cheeks and annular hyperkeratotic lesions with a warty appearance over arms and elbows in a symmetrical and linear configuration (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Erythematous keratotic plaques over the cheeks and annular hyperkeratotic lesions with a warty appearance over arms and elbows in a symmetrical and linear configuration.

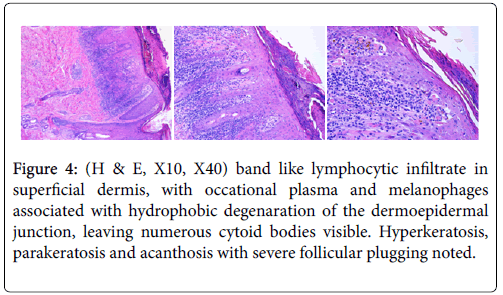

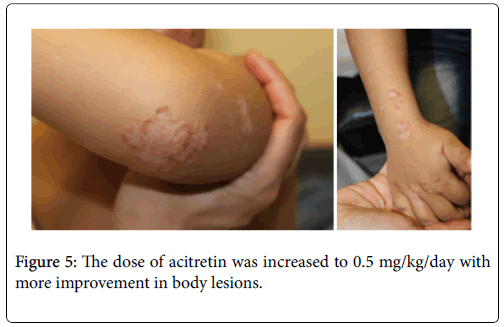

Two punch biopsies were taken for histopathologic evaluation. Findings were similar in all specimens and similar to the first case (Figure 4). DIF was negative. The diagnosis of KLC was retained. Patient was started on 0.3 mg/kg/day acitretin with decrease in hyperkeratosis over extremities after 2 months of treatment. However, no improvement in facial lesions was noted. Therefore, the dose of acitretin was increased to 0.5 mg/kg/day with more improvement in body lesions (Figure 5).

Figure 4: (H & E, X10, X40) band like lymphocytic infiltrate in superficial dermis, with occational plasma and melanophages associated with hydrophobic degenaration of the dermoepidermal junction, leaving numerous cytoid bodies visible. Hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis and acanthosis with severe follicular plugging noted.

Figure 5: The dose of acitretin was increased to 0.5 mg/kg/day with more improvement in body lesions.

KLC was first described in 1895 by Kaposi who used the term “lichen rubber accuminatus verrucosus et reticularis” to describe this entity [4]. In 1938, Lajos Neckam reported the case of the same patient seen by Kaposi and termed the disease “Parakeratosis striata lichenoides”. In 1965, Margolis et al. coined the term “keratosis lichenoides chronica” to describe a patient with a retiform pattern of lichenoid papules, a hoarse voice, and a seborrheic dermatitis-like lesions over the scalp and face [4,5]. KLC presents mainly in adults, between 20 and 40 years of age with a slight predominance in males [4,6]. It is classically characterized by the appearance of hyperkeratotic, lichenoid papules symmetrically distributed in a typical linear or reticular pattern [4,5]. The etiology of the disease has not been identified yet. Mode of inheritance, influence of any other genetic alteration, relationship with any drugs or infection, have not been defined [7]. Some conditions have been described in association with KLC (Table 1), but none of these associations have been established.

| Author | Age | Gender | Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ricardo et al. [17] | 66 | Male | KLC after resolution of erythroderma following treatment with oral azithromycin |

| Vernassiere et al. [18] | 35 | Male | Prolonged exposure to a source of heat [infrared radiation) |

| Marzano et al. [19] | 73 | Female | Multiple myeloma |

| Mansur et al. [1] | 44 | Male | Atypical sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation |

| Nijsten et al. [11] | 48 | Female | Autoimmune hypothyroidism |

| Grunwald et al. [20] | 53 | Male | Hypothyroidism |

| Masouye et al. [21] | 27 | Female | Tuberculosis |

| Lombardo et al. [22] | Male | Lymphoma | |

| Menter et al. [23] | 3 patients | Toxoplasmosis | |

| Bahadoran et al. [24] | 27 | Male | Mycosis fungoides |

| Jayaraman et al. [25] | 47 | Male | Syphilis |

| Braun-Falco et al. [26] | 61 | Female | Neurological diseases |

Table 1: Some conditions have been described in association with KLC.

Juvenile onset KLC is rarely reported in the literature [8]. To our knowledge, there are only 34 reported cases of juvenile onset KLC. 4 of the reported cases were congenital and 10 cases had a family history of similar eruptions suggesting an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance [5]. Table 2 outlines only the pediatric cases in literature with reported clinic and histopathological features. No familial cases have been reported in the adult onset KLC. According to Boer diagnosis of KLC should be made for patients presenting with at least two clinical and one histological feature:

| Author | Age | Gender | Age at onset | Family History | Keratoderma | Ocular | Nails | Oral | Alopecia | Hyperhidrosis | Genital | Pruritis | Biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 18 months | Male | 3 months | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| Case 2 | 2 years | Male | 4 months | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + |

| Singh et al. [27] | 16 years | Male | 6 months | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | + |

| Oyama et al. [12] | 12 years | Female | 2 years | - | + | - | Reticular streaks | + | - | - | - | + | + |

| Ghorpade [4] | 4 years | Male | 4 years | ? | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| Torrelo et al. [28] | 20 months | Male | 9 months | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + |

| Ruiz-Maldonado et al. [5] | 6 years | Male | 3 month | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | + |

| 6 years | Male | 1 year | + | - | - | - | Ulcerations | - | - | - | ? | + | |

| 6 months | Male | 4 months | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ? | - | |

| 17 years | Female | 4 months | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | |

| 17 years | Male | 4 months | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | |

| 2.5 years | Female | Congenital | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | |

| Ryatt et al. [29] | 16 years | Boy | 13 years | ? | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + |

| Arata al. [20] | 7 years | Female | 4 months | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ? | + |

| 8 years | Male | 6 months | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ? | - | |

| Redondo et al. [8] | 2 years | Female | 6 months | ? | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| Patrizi et al. [2] | 4 years | Male | 2 years | - | + | Conjunctivitis | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| Lang [35] | 24 years | Male | congenital | - | - | - | Longitudinal ridging, spliner hemorrhage | Ulcers | - | - | - | ? | + |

| Adişen et al. [10] | 20 years | Male | 11 years | - | + | Conjunctival hyperaemia | Dystrophic changes | Palatal erosions | - | - | - | - | + |

| Koseoglu et al. [13] | 19 years | Male | 11 years | ? | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| Ezzine-Sebai et al. [31] | 23 years | Female | 3 years | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | ? | + |

| Barriere et al. [32] | 30 years | Male | congenital | + | + | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Reynaud et al. [33] | 2 years | Female | 4 months | + | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Geng et al. [34] | 9 years | Male | 1 year | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | ? | + |

Table 2: Associated clinical features.

• Chronic facial lesions reminiscent of seborrheic dermatitis.

• Tiny papules on the trunk and extremities, which assumed linear and reticulate shapes by way of confluence of lesions, with infundibulocentric papules and papules around acrosyringia.

• Histological feature: lichenoid dermatitis with numerous necrotic keratinocytes and parakeratosis [7].

Clinical presentation of juvenile onset KLC differs from that of adults, which makes the diagnosis difficult in the pediatric population. Skin lesions in children tend to be more erythematous with an annular shape and lack the typical linear retiform and violaceous aspect seen in adults [5]. Topography may also vary in the two populations. In children, lesions first appear on the face then limbs and usually spare the trunk whereas in adults, the eruption starts on the limbs with secondary face involvement (Table 3). A vascular variant with telengiectasia has been described in two adult patients but not reported in pediatric patients [8,9]. Alopecia of the forehead, eyelashes, or eyebrows is present in 22% of pediatric cases, however, no alopecia is reported in adults (Table 3) [4]. Oral findings were more common in the adult onset KLC (54%) as compared to the juvenile onset KLC where oral involvement was noted in 23% of cases [4,6]. Ocular lesions are present in 9% of pediatric cases as compared to 54% of adult cases [8]. No genital involvement has been reported in the literature in the pediatric population. Nail involvement is more common in adults (33%) than in the pediatric population (9%) [6]. Keratoderma is present in 23% of juvenile onset KLC cases as compared to 50% in the adult population [4,6]. One case of hyperhidrosis has been described in a 9 months infant (Table 2).

| Adult onset KLC | Pediatric onset KLC | |

|---|---|---|

| Morphology of skin lesions | •Typically violaceous lichenoid hyperkeratotic papules (most frequent). •Erythemato-squamous plaques and Telengiectatic lesions (least frequent) •Linear or reticular pattern •Trunk, extremities, face |

•More erythematous than violaceous. •Lichenoid hyperkeratotic papules (least frequent). •Erythemato-squamous plaques (most frequent). •Rather annular then reticular pattern •Extremities and face with sparing of the trunk |

| Distribution of skin lesions | Limbs then progress to the face | Face then progress to the limbs |

| Pruritis | 23% of cases | 64% of cases |

| Alopecia | Not reported | 18% of cases |

| Oral involvement | 54% of cases | 23% of cases |

| Ocular involvement | 54% of cases | 23% of cases |

| Nail involvement | 33% of cases | 9% of cases |

| Keratoderma | 50% of cases | 23% of cases |

Table 3: Adult vs. Pediatric KLC.

Adult onset and juvenile onset KLC present with similar histopathologic characteristics. Histological finding in KLC are relatively uniform, consisting of a lichenoid infiltrate with epidermal changes [5,10]. In all reported cases of juvenile onset KLC, the lichenoid infiltrate is a prominent histopathologic feature (Table 4). The epidermis shows irregular acanthosis with focal epidermal atrophy, marked hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, necrotic keratinocytes, and hyper or hypo-granulosis [6,10]. Parakeratosis, a pivotal histopathologic feature in differentiating KLC from LP, is present in 12 out of 16 reported patients with juvenile onset KLC. Spongiosis can be observed. A dense, lichenoid, lymphohistiocytic and plasmocytic dermal infiltrate with focal degeneration of the basal layer and numerous necrotic keratinocytes is usually present. Colloid bodies are variably present. Telengectasia of the superficial dermal vessels is sometimes noted. The presence of cornoid lamellae has also been reported (Table 4) [6,10]. Differential diagnosis includes annular psoriasis, hypertrophic or verrucous lupus erythematosus (HLE) and hypertrophic lichen planus (HLP). Table 5 summarizes the differences in histological findings of these 3 entities.

| Authors | Acanthosis | Epidermal atrophy | Hyperkeratosis | Parakeratosis | Vacuolar alteration | Lichenoid infiltrate | Follicular plugging | Basal cell degeneration | Cytoid bodies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | + | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | + |

| Case 2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Singh et al. [27] | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + |

| Oyama et al. [12] | + | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | + |

| Ghorpade [4] | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - |

| Torrelo et al. [28] | + | - | + | + | + | + | - | - | + |

| Ruiz-Maldonado et al. [5] | + | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | - |

| + | - | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | |

| + | - | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | |

| ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | ? | ? | + | |

| Ryatt et al. [29] | + | ? | ? | + | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Arata et al. [30] | + | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | + |

| Redondo et al. [8] | + | + | + | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| Patrizi et al. [2] | + | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| Lang [35] | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | - |

| Adişen et al. [10] | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| Koseoglu et al. [13] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| Ezzine-Sebai et al. [31] | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| Geng et al. [24] | + | - | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

Table 4: Histopahtology.

| Histological findings | KLC | HLP | HLE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperkeratosis | + | + | + |

| Parakeratosis | Focal | + (Not in LP) | variable |

| Acanthosis | Variable | Marked, Irregular (saw tooth) | +/- (Usually atrophic epidermis) |

| Dense bandlike inflammation in upper dermis | ++ (Lymphohistiocytic + plasma cells) |

+ (Lymphohistiocytic) |

Patchy |

| Melanophages | visible | visible | - |

| Cytoid bodies | ++ | + | + |

| Deposits of mucin/Fibrosis dermis | - | - | + |

| Perivascular & periadnexal infiltrate | -/+ | - | + |

| Alteration of basal layer | + | + | + |

| Follicular plugging | + | - | ++ |

| DIF | Highlights cytoid bodies | Highlights cytoid bodies/linear fibrillar band of fibrin at DEJ | Granular deposition (IgG/IgM) at DEJ & around hair follicles |

Title 5: Histological differentiations.

The treatment of KLC is disappointing in the majority of cases. Tacrolimus 0.1% ointment in combination with topical calcipotriol or tacalcitol has been used with variable results [4,10-13]. The exact mechanism by which tacrolimus and Vitamin D analogues exert their effect on KLC is still unknown [10]. Oral retinoids (0.5 mg/kg/day) have been shown to be effective in the treatment of KLC [10]. Flattening of the skin lesions was noticeable within the first month of treatment with complete resolution of skin lesions after 4-6 months. Improvement was maintained over 8-9 months [4,10,11,14]. Many authors reported cyclic improvement of skin lesions upon exposure to sunlight. Whether used as monotherapy or combined with oral retinoids, phototherapy has been reported as the most effective treatment modality mainly due to its anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, and antiproliferative effect [4,5,8,13]. It includes the use of natural sunlight, ultraviolet A, ultraviolet B, photochemotherapy, or any combination of these. In a review of treatment options by Pistoni et al. [15], phototherapy or retinoid alone or in combination were the most effective treatment for KLC. Clinical response was achieved in 56% of patients receiving retinoids (mostly acitretin at a dose of 0.3-0.6 mg/kg/day) [16]. Juvenile onset KLC is a challenging diagnosis because the clinical presentation and histopathologic features are different from the adult from. Pediatric KLC should therefore be considered as a subset of adult onset disease with specific genetic and clinical characteristics [5].

Citation:

Julien B, Pierre K, El-Haber C, Samer G, Fatima, et al. (2019) Two Cases of Pediatric Keratosis Lichenoides Chronica with Review of the Clinical and Hitopathological Features of Pediatric versus Adult Presentation and Treatment with Acitretin. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res 10:476. doi: 10.4172/2155-9554.10.476

Received: 03-Oct-2018 Accepted: 17-Dec-2018 Published: 08-Jan-2019

Copyright:

© 2019 Julien B, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.