Journal of Tourism & Hospitality

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0269

ISSN: 2167-0269

Short Communication - (2021)Volume 10, Issue 6

As highlighted in the literature, the tourism sector has grown increasingly competitive and complex. The sector’s fragility has increased, owing to the “complexification” of the consumption patterns and volatility of the modern world (pandemics, climate change, geopolitical events, etc.). In parallel, instances of regional economies for which tourism is a key developmental sector have grown in number and, therefore, demonstrate increased vulnerability to the tourism sector’s inherent volatility.

This observation highlights the importance of sustainability regarding the sector’s future development as a hedge against the industry’s volatility [1-4]. Tourism is influenced by events that are external to each particular destination’s frame of reference, and it might be considered overly ambitious an undertaking to devise a plan that protects tourism from such varied events. However, it would be reasonable to propose that sustainability should at least focus around preserving each destination’s special attributes (that were initially leveraged to propel sector growth or can form the cornerstone of destination branding). Such attributes typically concern the destinations’ natural and cultural resources. Proactive conservation of these resources would provide significant benefits for all engaged stakeholders, by ensuring stability in the sector’s development, while mitigating the well-documented adverse effects that arise owing to (Over touristification).

The tourism sector has been considered Greece’s heavy industry across the last decades. The sector’s positioning, relative to other global destinations, is based on the favorable climate conditions; the country’s extended coastline and pristine natural land/ seascapes; and its significant tangible and intangible cultural wealth. Its sustainable future development is critical and is referred to in most policy texts at a national/regional level. Nonetheless, certain drawbacks have been observed and repeatedly ascertained with regards to the sector’s development.

These include sharp seasonality, with the main volume of tourist flows gathered in the summer season; lack of diversification in terms of value propositions, using cultural/natural ensemble as tourism traffic magnets; and the sector’s overreliance on the 3S (Sun-Sea-Sand) model, to name a few.

In fact Greece has been promoting the image of a ‘summer myth’ destination for decades. Nonetheless, the Greek state has consistently committed to the diversification of the tourism product through strategic policy choices that target to widen the breadth of the sector’s value proposition through the spatiotemporal dispersion of relevant activity. However, developmental plans typically require that areas develop along lines that are often invalidated or rendered less attractive due to local conditions. For example, potential hindrances arise in areas that have historically followed different development patterns, e.g., former industrial or agricultural areas. These hindrances are not solely material in nature, such as lack of required public or private infrastructure. They entail lack of relevant market knowhow, human capital and entrepreneurial culture; and are, understandably, impacted by inertia, in the form of reluctance to shift planning focus from one that facilitated the development of well-established economic activity to novel sectors.

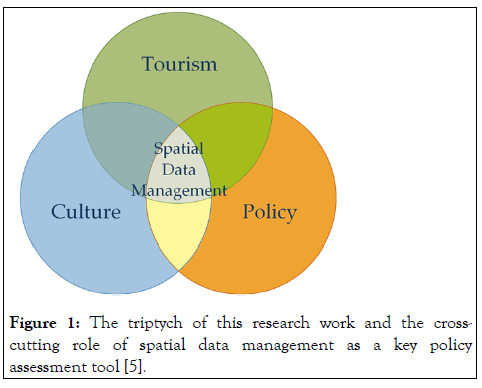

In the Fourth Industrial Revolution Age, marked by advances regarding the collection, storage, analysis and visualization of big data, it is self-evident that there is value to be obtained in leveraging novel approaches/tools. Taking such an approach, it is possible to distill data into information and feed insightproducing analyses. Following this process, potential for assessing/monitoring performance of strategic guidelines in the sector is increasing; same holds for policy remediation, by means of identifying failures and intensifying policy efforts to promote attractive/durable products that are based on the establishment of the tourism-culture nexus (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The triptych of this research work and the crosscutting role of spatial data management as a key policy assessment tool [5].

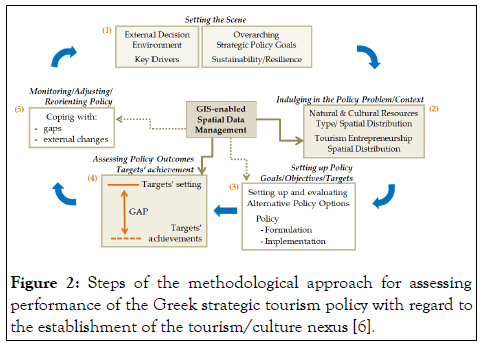

Such an analysis is placed at the heart of this study, aiming to identify gaps and thus motivate evidence-based policy making. Towards this end, the stages of the policy cycle [6,7] Figure 2 form the methodological ground.

Figure 2: Steps of the methodological approach for assessing performance of the Greek strategic tourism policy with regard to the establishment of the tourism/culture nexus [6].

Policy-cycle represents a dynamic framework, through which the present state is analyzed in the context of developmental goals and is monitored using data. Based on that, alternative policy scenarios’ formulation is facilitated, and their performance is benchmarked against initial goals, thereby enabling policy assessment and relevant adjustments. Such an approach is used to allow interested parties a high-level view of the current policy performance regarding tourism development; and is exemplified by use of data provided from the Greek State and Open Street Map. By taking a GIS-enabled approach, a high-level analysis of the said data is achieved; and a comparison of the distribution of tourism-related commercial activity (business locations) and natural/cultural resources is accomplished. This unveils a diversified pattern of tourism development on a regional (NUTS2) level, with areas displaying a very low (unexploited resource wealth) or high tourism intensity.

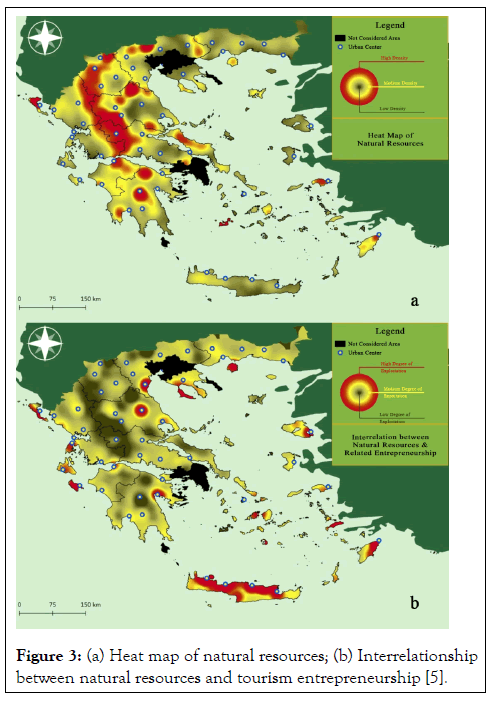

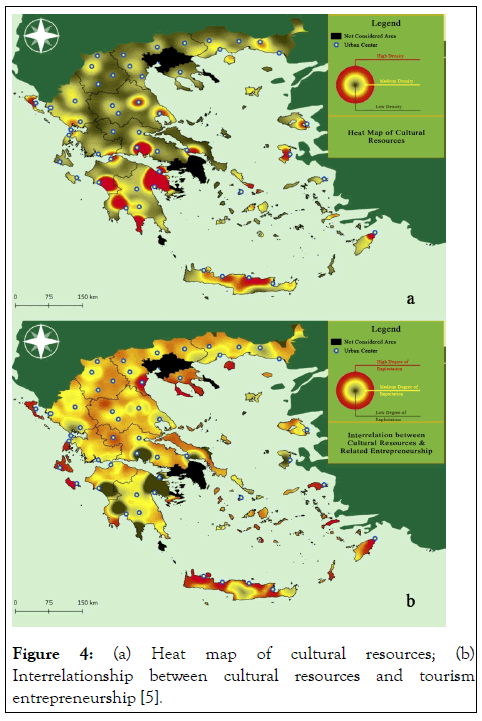

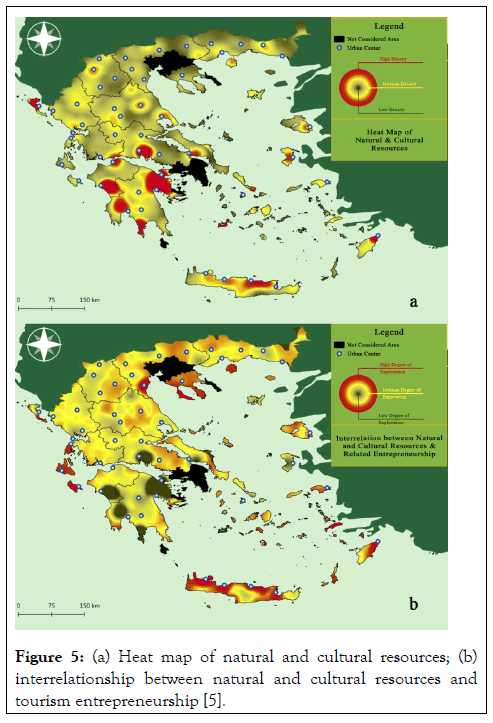

The adoption of the ‘policy cycle’ framework, coupled with spatial data management and mapping of both the natural/ cultural resources and the tourism entrepreneurship have proven quite effective in demonstrating policy ineffectiveness towards a harmonious, hand-in-hand coexistence of tourism with the culture/nature ensemble in Greece. Indeed, based on the research findings (Figures 3-5), the overarching developmental pattern of the Greek tourism sector proved to be inconsistent with the goals set out in relevant strategic documents. More precisely, tourism business activity is concentrated in coastal zones and island areas, placing local resources under significant duress, and further entrenching the 3S model. On the contrary, areas in the Greek mainland, although disposing abundant cultural/natural resources, have largely remained underdeveloped as can be seen in Figures 3-5. More targeted policies need to be in place that are capable of grasping local potential and are facilitated by tools that allow for the collection/analysis of significant volumes of data. Such data, particularly of the geospatial variety, can: provide insights regarding the destination maturity/saturation, highlight developmental potential, and most importantly, allow for monitoring the performance of strategic policy plans.

Figure 3: (a) Heat map of natural resources; (b) Interrelationship between natural resources and tourism entrepreneurship [5].

Figure 4: (a) Heat map of cultural resources; (b) Interrelationship between cultural resources and tourism entrepreneurship [5].

Figure 5: (a) Heat map of natural and cultural resources; (b) interrelationship between natural and cultural resources and tourism entrepreneurship [5].

Citation: Lampropoulos V, Panagiotopoulou M, Stratigea A (2021) Unfolding the Potential of the Culture-Tourism Nexus in Greece: A Data- Enabled Methodological Approach. J Tourism Hospit.10: 479.

Received: 29-Nov-2021 Accepted: 13-Dec-2021 Published: 20-Dec-2021

Copyright: © 2021 Lampropoulos V, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.