Fisheries and Aquaculture Journal

Open Access

ISSN: 2150-3508

ISSN: 2150-3508

Research Article - (2023)Volume 14, Issue 1

This study examined the value chain of catfish products in Ibadan metropolis. The data used was from a primary origin. The instrument of data collection was structured questionnaires and in-depth interview. Purposive sampling method using snowballing techniques was employed to select 50 catfish farmers and 50 catfish marketers in the study area. While random sampling technique was engaged for selection of 100 catfish consumers. Descriptive statistics, profitability and value chain analysis techniques were used to analyze the data collected. The findings revealed that majority of the actors in the catfish value chain were relatively young adults with moderate household size and having higher level of education. The catfish farmers should be induced with productive resources to harness their potentials catfish production. Also, catfish experts should collaborate and work on local feed materials to reduce the cost of catfish feeds and catfish marketing cooperative or self-help groups should be developed.

Catfish; Value chain; Ibadan; Nigeria

The links between catfish production and consumption are undertaken by different set of group of agents. For instance, production is handled by the catfish farmers, catfish outputs are engaged either by the processors or by the marketers at different channels and many other economics activities take place along the value chain before reaching the last consumers. John (2006) submitted that the responses of different economic agents to market forces may not necessarily be symmetric, implying that changes in the raw materials or products prices at the upstream level (production) may exhibit different responses at the downstream level (wholesalers or retailers) and vice versa.

For instance, asymmetry in catfish price transmission had been reported. [13] Stated that consumer’s complaint that retail prices rise more quickly when prices are rising than they fall when prices are falling. More importantly, catfish farmers have not been positively benefiting by the responses of market forces when compared with catfish marketers or processors. However, the foregoing submissions lack sufficient empirical proof because most of the previous research works, findings and submissions failed to consider the activities of all economic agents (farmers, wholesalers, retailers, processors and consumers) in catfish value chain.

Available literature considered each economic agent in catfish downstream in isolation and the asymmetry nature in catfish price transmission had been empirically revealed [1,2,3] researched were basically of catfish production. While [4-6] beamed their research light on catfish markets issues. Catfish consumption and preferences were the main focus of [7,8,9]. The policy recommendations from these would lack sufficient and adequate scientific findings that could serve as basis for a comprehensive and sustainable catfish policy.

Achievement of strategic sustainable development in catfish is attainable when necessary empirical data and information that enhance basic understanding of inter-link of relationship and activities that existing among the stakeholders. Moreover, to establish the nature of economic activities, costs and benefits accrue to each economic agent in catfish value chain make the focus and objective of this research relevant.

The principle of value chain analysis (VCA) is capable of eliciting some latent information that the previous research methodologies are unable to shed light on. Therefore, at the end of this research work, the following questions would be adequately answered. What are socioeconomic attributes of the major actors in catfish in the study area? Are there disparities in their profit margin along the catfish chain?

Conceptual framework of catfish value chain

Value chain has been described as the full range of activities which required bringing a product (catfish) or servicing from conception, through different phases of production to the final consumer [10]. This means the value chain stars when producer (farmer) sought for inputs (catfish fingerlings) in combination with other necessary resources that lead to physical transformation of fingerlings to table catfish products to the final consumer. The number of stakeholders that would handle and add value to the catfish in the chain before the product finally reach the ultimate consumer is a function of time utility, place utility and form utility [11]. The inter-links of the catfish stakeholders identified along the value chain in the study area are shown in the Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Major actors of catfish identified in value chain in the study area.

Study Area

The study was conducted in Ibadan, the capital city of Oyo State of Nigeria, is the largest indigenous city in West Africa. It is located in south western part of Nigeria (latitude 7.4 and longitude 3.9) in a hilly settlement with urban and rural features. It has an estimated land area of 3,123.30 km square. Tropical rain forest is the vegetation of Ibadan metropolis which makes it suitable for catfish farming. The population of this study consists of all catfish actors in the study area.

Source and sampling procedure of data collection

The data used was from a primary origin and was collected separately from catfish farmers, catfish marketers (wholesalers and retailers) and catfish consumers. The instrument of data collection was structured questionnaires and in-depth interview. Different structured questionnaires were designed for the catfish stakeholders to elicit necessary information that suit the main objectives of this study. The resources or inputs used in catfish production and socioeconomics variables were contained in the catfish farmers’ questionnaires, marketing variables and socioeconomic variables were the main content of the questionnaires of the catfish marketers and the catfish consumers’ questionnaire was contained the relevant socioeconomics variable required for this study. Purposive sampling method using snowballing techniques was employed to select 50 catfish farmers and 50 catfish marketers in the study area. While random sampling technique was engaged for selection of 100 catfish consumers in connection with the catfish marketers.

Analytical techniques

Descriptive statistics, profitability and value chain analysis techniques were used to analyze the data collected for this study. Descriptive statistics used include frequency distribution, mean and percentage for the socioeconomics variables of the stakeholders. The profitability was used for the gross margin analysis of the catfish farmers’ production and marketer’s activities respectively. While the value chain analysis include the analysis of relative contribution of inputs categories to total price build-up and distribution of profit among the catfish subsector as used by [12,13].

Profitability analysis

Gross margin analysis:

Return on cost (ROC):

Benefit Cost Ratio (BCR):

Where:

GMP = Gross Margin Profit (N),

TR = Total Revenue (N) & TVC = Total Variable Cost (N)

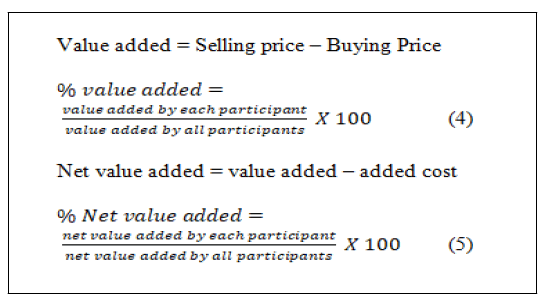

Value chain analysis of catfish

Note: Added cost id the transaction cost during the movement of catfish products.

Table 1 above revealed that catfish production was dominated by male farmers (74%), while the remaining 26% of the catfish farmers were female. Generally, farming activities has been perceived as occupation of men, particularly in south-west part of Nigeria where this study was carried out. For Nigeria to attain food sufficiency there is need to encourage more women to engage in catfish production.

| Variables / Actors | Catfish Farmers | Catfish Marketers | Catfish consumers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | No | % | No | % | No | % |

| Male | 37 | 74 | 24 | 48 | 47 | 47 |

| Female | 13 | 26 | 26 | 52 | 53 | 53 |

| Total | 50 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 9 | 18 | 17 | 34 | 34 | 34 |

| Married | 41 | 82 | 33 | 66 | 63 | 63 |

| Divorced | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 50 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Education qualification | ||||||

| Primary | 6 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| Secondary | 3 | 6 | 12 | 24 | 19 | 19 |

| Tertiary | 41 | 82 | 37 | 74 | 76 | 76 |

| Total | 50 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| < 40 | 20 | 40 | 23 | 46 | 61 | 61 |

| 40-45 | 11 | 22 | 20 | 40 | 16 | 16 |

| 46-49 | 8 | 16 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 9 |

| 50-55 | 11 | 22 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 10 |

| >55 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Total | 50 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mean | 42 | 38 | 38 | |||

| Standard deviation | 8 | 7 | 10 | |||

| Household Size | ||||||

| 01-Feb | 2 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 12 |

| 03-Apr | 17 | 34 | 24 | 48 | 36 | 36 |

| 05-Jun | 25 | 50 | 17 | 34 | 42 | 42 |

| >6 | 6 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| Total | 50 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mean | 5 | 6 | 5 | |||

| Standard deviation | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

Table 1: Socioeconomics characteristics of the participants in the value chain.

There was no gender discrimination against catfish marketing in the study area. This was found evident insignificant gender disparity among the catfish marketers. This implies that both men and women engaged in catfish marketing activities as sources of their livelihood. However, this was contrary to the findings of Ali et al., (2008)t that reported 81.67% catfish marketers as male and 18.33% as female. Moreover, the result also revealed that there was no gender barrier against the consumption of catfish products. 53% of the catfish consumers sampled were female and 47% were male.

The result shows that larger percentages of the value chain actors sampled were married; catfish farmers (82%), catfish marketers (66%) and catfish consumers (63%). This shows that catfish contribute significantly to the livelihood and well-being of the married respondents. However, there was no divorced peopled participated in catfish production and marketing, while small percentage of single participated in catfish production (18%) and catfish marketing (34%). According to this results, there is need to encourage single to engage in catfish production and marketing for reduction in the level of unemployment. Also, singles are mostly young school leavers that have higher productivity capacity and tend to be more efficient in terms of their production output than consumption. The outcome of the educational qualifications revealed that most of the stakeholders in the catfish chain in the study area have postsecondary educational qualification. 82% of the catfish farmers, 74% of catfish marketers and 76% of catfish consumers have post-secondary education qualifications. Higher level of education qualifications among the stakeholders would promote and enhance their source of livelihood and lead to improvement of their standard of living.

The average age of the fish farmers was 42 years with standard deviation of 8 years. Also, the mean age of the catfish marketers was 38 years and 7 years as standard deviation, while average age of the catfish consumers was 38 year with standard deviation of 10 years. Generally, the results revealed that almost al the catfish stakeholders were relatively younger and were at their active years. This indicates that catfish subsector of fisheries could experience rapid growth and development if necessary enabling and conducive environment is available.

The findings from analysis of the household of catfish farmers revealed that 50% have family size between 5 and 6 people, 34% have family population ranging between 3 and 4 people, while 12% of the catfish farmers keep family size that is more than 6 members per family. The average family size was found to be 5 members with standard deviation of 1. 48% of consumers’ have between 1 and 4 persons per family, while 42% of the consumers have between 5 and 6 persons per household. The mean family size of the catfish consumers was 5 persons with standard deviation of 2 persons.

Table 2 above present the results of gross margin, return on cost and benefit cost ratio analyses of both catfish famers and marketers. According to production cost, catfish feed was found to be major cost, which was6 64% of the total variable cost. It was reported by the catfish farmers sampled that feeds and feeding management was the main challenge of catfish production. On average, the labour cost gulped 20% of the catfish production while juveniles or fingerlings cost constituted 8%. Also 3% and 5% of the total variable cost were incurred on pond fertilization and transportation respectively.

| Production inputs | Average Cost | % of Cost | Marketers inputs | Average Cost | % of Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juveniles / Fingerlings | 25524 | 8 | Catfish bought | 400000 | 87.8 |

| Labour | 64829 | 20 | Labour | 23390 | 5.1 |

| Feeds | 212749 | 64 | Storage | 17000 | 3.7 |

| Fertilizer / lime | 10558 | 3 | |||

| Transportation | 15500 | 5 | Transportation | 15000 | 3.3 |

| Miscellaneous | 2000 | 1 | |||

| Total variable cost | 330890 | 100 | Total variable cost | 455390 | 100 |

| Income | 5480890 | Income | 550000 | ||

| Gross Margin | 217197 | Gross Margin | 94610 | ||

| Return on Cost (ROC) | 0.66 | Return on Cost (ROC) | 0.21 | ||

| Benefit cost Ratio (BCR) | 1.66 | Benefit cost Ratio (BCR) | 1.21 |

Table 2: Gross Margin Analysis of catfish production and Marketing.

Furthermore, the mean value of the return on cost and benefit cost ratio of catfish analysis were 0.66 and 1.66 respectively. Ceteris paribus, these financial indicators mean that on average, 66 kobo was gained as return on one naira spent on production of catfish. On the marketing aspect of the catfish value chain, the main component of the costs was the purchasing cost (87.8%). This implies that to start catfish marketing, about 88% of the initial capital will be for purchasing the quantity that will meet the estimated demand. The remaining capital will be shared for labour (5.1%), transportation cost (3.7%) and catfish preservation and storage will amount to 3.3% of the total variable marketing cost. Moreover, the benefit-cost ratio in catfish marketing was 1,21 and return on cost was 21%. This means that catfish marketing was relatively profitable.

Note: value added is the difference between buying price and selling price per kilogram of catfish while percentage value added is the proportion of value added at the level of individual stakeholder. Net value added is difference between the value added and added costs (the cost includes transportation cost, processing cost, preservation cost and other miscellaneous costs).

The Table 3 above presents the distribution of profit (N /kg) share among the stakeholders in the catfish value chain considered in this study. The outcome of the analysis shows that catfish marketers have 86.21% of the value added while the catfish farmers have 13.7%. The percentage of net value added revealed that 72.72% of the profit in the value chain accrues to the catfish marketers while 27.28% of the profit accrued to the farmers. This was similar to the findings of Sinh et al (2011) that reported that 87.9 to 93.4% of profit was mainly for the traders while 6.2 to 6.6% of the profit was for the farmers.

| Description | Farmers | Marketers | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selling price (N/kg) | 400 | 550 | |

| Buying price (N/kg) | 376 | 400 | |

| Value-Added | 24 | 159 | 174 |

| % Value-Added | 13.79 | 86.21 | 100 |

| Added costs (N) | - | 95 | |

| Net value Added | 24 | 64 | 88 |

| % Net Value-Added | 27.28 | 72.72 | 100 |

Table 3: Distribution of profit (N /kg) in catfish value chain.

The findings from this research revealed that majority of the actors in the catfish value chain were relatively young adults with moderate household size and having higher level of education. These socioeconomic variables and indicators pointed to the fact that the stakeholders in the catfish value chain were in their active and productive stage. Catfish feed is the highest cost among production cost components. The analysis of the proportion of total profit sharing among the actors on the catfish value chain indicated that a typical marketer gained about 72.72% while on average a farmer gained 27.28%.

The young catfish farmers should be provided with productive resources to harness their potentials catfish production. Also, catfish nutritionists, fisheries and economists experts should collaborate and more research should be done on local feed materials to reduce the cost of catfish feeds. More importantly, catfish farmers should formulate strategic marketing policies for catfish products through catfish marketing cooperative or selfhelp groups and this would lead to more economic benefits, improvement of catfish welfare and standard of living.

Citation: Olaniyi OZ, Oluyemisi AA, Motunrayo OB (2022) Value Chain of Catfish Products in Ibadan Metropolis, Oyo State, Nigeria. Fish Aquac J. 14:324.

Received: 02-Mar-2023, Manuscript No. FAJ-23-24213; Editor assigned: 03-Jan-2023, Pre QC No. FAJ-23-24213(PQ); Reviewed: 18-Jan-2023, QC No. FAJ-23-24213; Revised: 25-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. FAJ-23-24213(R); Accepted: 30-Jan-2023 Published: 31-Jan-2023 , DOI: 10.35248/2150-3508.23.14.324

Copyright: © 2023 Olaniyi OZ, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.