Forest Research: Open Access

Open Access

ISSN: 2168-9776

ISSN: 2168-9776

Research Article - (2023)Volume 12, Issue 5

Objective: Ecological monitoring and sustainable management of forest ecosystems require deep knowledge and understanding of biodiversity. Notwithstanding this, useful data are still limited in most of the tropical regions. This study assessed the status of biodiversity in sacred and classified forests in northwestern Benin.

Methodology and results: Woody plants were inventoried in 2 sacred and 3 classified forests within plot sizes of 50 × 30 m. Relative frequencies and Pearson Chi-square independence tests were performed to identify the top 20 and 10 families and species, respectively. Biodiversity indicators such as Shannon's entropy, species richness and Gini- Simpson index were assessed as well.

Conclusions and application of findings: In the present study, we reported 76 species belonging to 58 genera and 27 families. The most abundant families were Fabaceae, Sapotaceae, Combretaceae, Meliaceae, Anacardiaceae and Rubiaceae. We also found a strong association of species families with forest types. Shannon's entropy values and Gini-Simpson indices differed significantly among forests. The diversity indices values were higher in classified forests than in sacred ones. Both classified and sacred forest shelter mostly species interesting for populations and researchers. All the inventoried species are in the threatened species category on the IUCN red list, with 3 vulnerable species (Khaya senengalensis, Vitellaria paradoxa and Afzelia africana) and 2 endangered ones (Pterocarpus erinaceus and Garcinia sp). These results revealed the relevance of local strategies to protect natural resources and the need of additional strategic actions for sustainable biodiversity conservation and management of these forests under anthropogenic pressures.

Biodiversity; Forests; Conservation; Sustainability; Benin

Forest ecosystems provide population with essential goods and services, and constitute a source of financial income. In Africa, around 600 million people depend on forest resources. Several raw materials from forests are commonly used by 80% of African population for health purposes. In addition, these ecosystems are of great importance in achieving sustainable development objectives, particularly those addressing poverty, food security, climate change, and desertification and biodiversity conservation issues [1].

Forests are suffering from human activities, which derived from land usage and agricultural practices. The impact of human activities and other antropogenic pressures are well documented. In fact, human actions have resulted in reducing of forests coverage as well as biodiversity, and unbalanced plant communities. The report published by the ‘’Banque Mondiale’’, indicated that forests of Benin have declined from 7.6 million to 5.9 million hectares from 2005 to 2015. Then, these losses represent 14% of the total forest areas of Benin in 2005. Therefore, it is an urgent need to take some actions to preserve plant diversity among forests.

The implementation of actions and policies to sustain forests preservation requires deep knowledge and understandings of biodiversity they gathered. Most of the challenges in assessing the diversity within forests rely on their types and complexities. Since then, great attention is being paid to diversity indices such as Shannon’s entropy and Simpson’s index in determining the abundance and diversity of species. Several studies have documented the conservation status of biodiversity among forests across Africa. However, these studies lacked of advanced analyses tools including Shannon's entropy and the Gini- Simpson index, and were limited to species richness index. Besides, they did not investigate the difference in biodiversity indicators among the conservation status of diverse forests such as sacred, community and classified forests. For example, Kouadio, et al. assessed the biodiversity among the dense forest of the dodo Voluntary Nature Reserve (NVR) in the southwest of Cote d'Ivoire using Shannon's entropy as an indicator. Accordingly, they inventoried 242 species with the Shannon's diversity indices of 3.008, 2.578, 3.506, and 2.455 in dense forest, secondary forest, fallow and savannah included respectively. Besides, Kitoko, et al. has recently pointed out higher species richness among sacred forest in the Kongo central province in the democratic republic of Congo. However, Ricotta pointed out the importance of improving these indices upon the study of species with special status.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, the ecological monitoring and sustainable management of forests are quite challenging as scientific data on the status of their biodiversity are lacking. These informations are of interest and require much attention than anthropogenic. In the present study, we assessed the status of biodiversity within sacred and classified forests under anthropogenic threats at Djougou district in Northwestern Benin [2-5].

Study site

This study was conducted at Djougou district in 5 forests including 3 classified and 2 sacred. This district is located in the Sudano-Guinean transition zone (7°30’N and 9°45''N), in the Bassila phytodistrict which is characterized by a sub-humid tropical climate with annual rainfall varying between 1200 mm and 1300 mm, and humidity index ranging from 2.7 to 3.9. The soils in this phytodistrict are tropical ferruginous types with deep waterlogging. The climax vegetation is dense forest semi-deciduous dominated by Khaya grandifoliola and Aubrevillea kerstingii. The genus Aubrevillea is endemic to this phytodistrict which species richness is estimated at 450 plant species with Leguminosae (15%), Rubiaceae (11%) and Euphorbiaceae (4%) as the more an abundant families [6,7].

Sampling and data collection

The methodology used for data collection was adapted from Salako, et al. Plants species were inventoried within plot sizes of 30 m × 50 m randomly set in each forests. The number of plots set per forest is summarized in Table 1.

| Forest | Name | Number of plots set |

|---|---|---|

| Classified | Belefougoun | 38 |

| Kilir | 11 | |

| Serou | 22 | |

| Sacred | Djadjangou | 18 |

| Yarakeou | 12 |

Note: The conservation status of each species inventoried was thereafter determined from the IUCN red list (Least Concern (LC); Near Threatened (NT); Vulnerable (VU); Endangered (EN)).

Table 1: Number of plots set per forest.

Statistical analyses

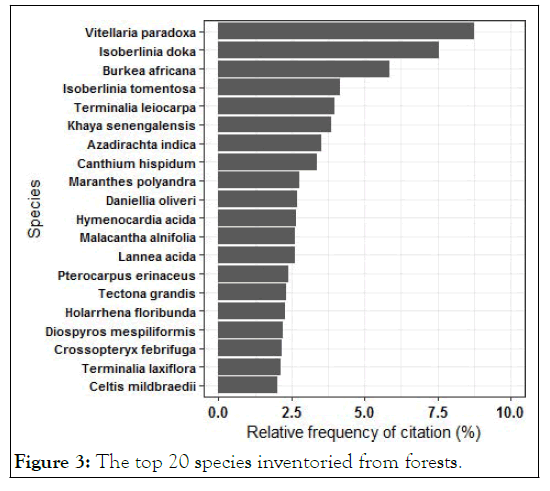

To describe the taxonomic diversity of the identified species, the number of families and genus were counted. The relative frequencies of occurrence were calculated to highlight the most represented families, as well as the top 20 species found in overall, and 10 per forest type. Pearson's chi-square independence test was performed on the n × p matrix (n refers to the top 10 species set in row, and p refers to type of forest set in column) to demonstrate the relationship between these two variables. The same analysis was carried out to measure the association of forest types with conservation status by referring to the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) red list. The biodiversity appreciation indices including species richness (total number of species), Shanon's entropy (equation 1) and the Gini-Simpson diversity index were calculated using the functions Chao Richness, Chao Shannon and Chao Simpson of the iNEXT package [8-12].

Where N is the total number of all species, and n is the total number of a specific species.

Statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical software (Version 4.0.0, R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria) [13-15].

Taxonomic diversity and variation of species among forest types

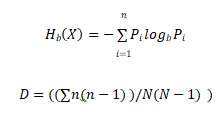

The inventory results pointed out 73 species belonging to 58 genera and 29 families. The Pearson’s chi-square test indicated a strong association of species families with forest types (X2=207.87, df=11, p<0.001). As indicated in Figure 1, the top 20 first families of species inventoried in both classified and sacred forests were mostly dominated by Fabaceae (RFC=28.49%) followed by Sapotaceae (RFC=11.36%), Combretaceae (RFC=9.13%), Meliaceae (RFC=7.83%), Anacardiaceae (RFC=6.03%) and Rubiaceae (RFC=5.82%) [16-18].

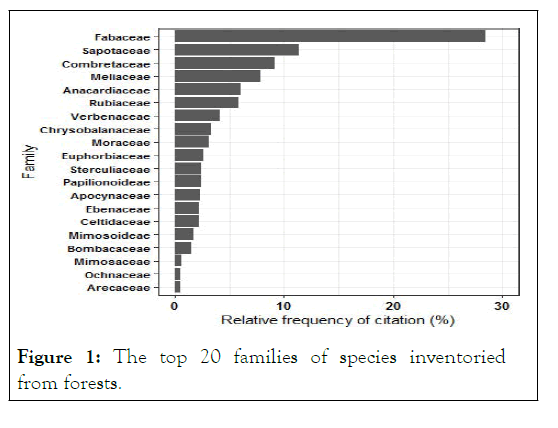

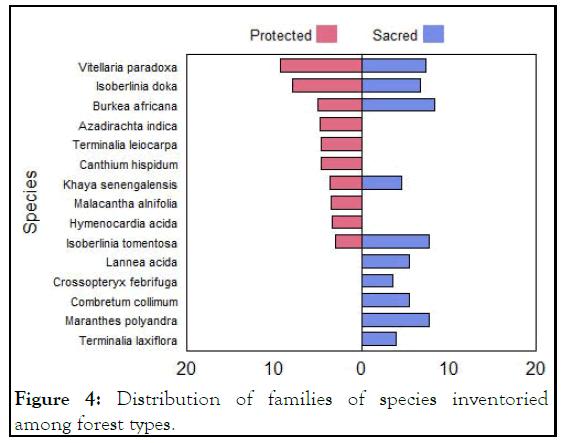

However, the families of Mimosoideae and Chrysobalanaceae were only found in sacred forests while that of Celtidacaea was reported from classified forests (Figure 2).

Figure 1: The top 20 families of species inventoried from forests.

Figure 2: Distribution of families of species inventoried among forest types.

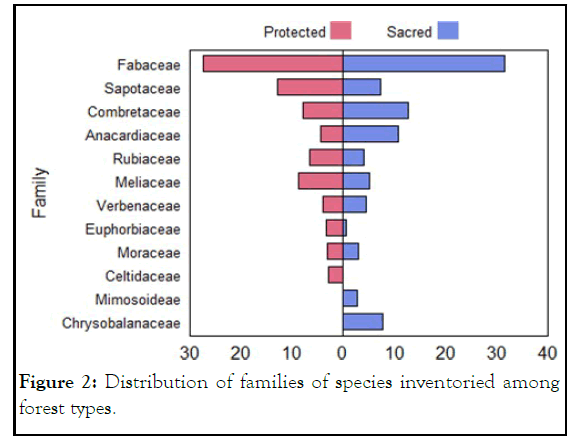

The top 20 first species inventoried among the forests were in overall dominated by Vitellaria paradoxa (8.75%), Isoberlinia doka (7.55%), Burkea africana (5.87%), Isoberlinia tomentosa (4.18), and Isoberlinia tomentosa (4.18%) followed by Terminalia leiocarpa (3.97%), Khaya senengalensis (3.86%), Azadirachta indica indica (3.53%) and Canthium hispidum (3.37%) (Figure 3). Besides, the Pearson’s chi-square test also indicated a strong association of the top 10 species to forest types (X2=435.07, df=14, p<0.001).

However, Azadirachta indica (4.77%), Terminalia leiocarpa (4.63%), Canthium hispidum (4.55%), Malacantha alnifolia (3.52%) and Hymenocardia acida (3.38%) were mainly reported from classified forests while Lannea acida (5.44%), Crossopteryx febrifuga (3.56%), Combretum collimum (5.44%), Maranthes polyandra (7.74%) and Terminalia laxiflora (3.98%) were found in sacred forests (Figure 4) [19,20].

Figure 3: The top 20 species inventoried from forests.

Figure 4: Distribution of families of species inventoried among forest types.

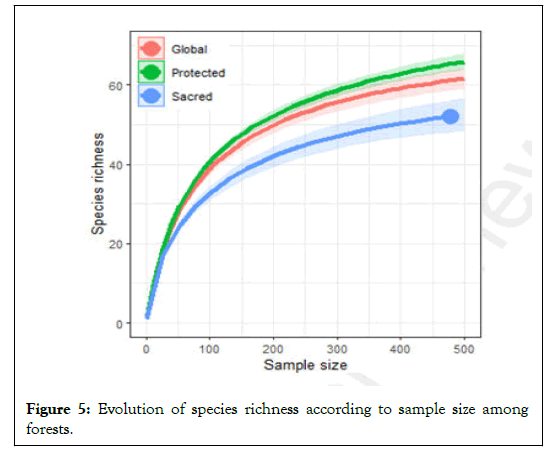

The results indicated that Shannon's entropy values differed significantly among of forest types (confidence interval values of 3.687 and 3.762 vs. 3.394 and 3.537 in classified and sacred forests, respectively at 95%) with the high value recorded in classified forests. Similarly, the estimated Gini-Simpson index value was higher in classified forests than in sacred ones (Table 2). However, even though the species richness value recorded in classified forest was higher than that of sacred forest, they were not significantly different [21,22].

The species accumulation curve also indicated that species richness increased along with increase in sample size (Figure 5).

| Estimated parameter | Forest | Observed value | Mean ± SE | (95% CLd) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shannon entropy | Classified | 3.687 | 3.714 ± 0.024 | 3.687–3.762 |

| Sacred | 3.394 | 3.458 ± 0.041 | 3.394–3.537 | |

| Overall | 3.776 | 3.802 ± 0.802 | 3.776–3.851 | |

| Species richness | Classified | 69 | 73.497 ± 4.799 | 69.814–93.839 |

| Sacred | 52 | 56.491 ± 3.962 | 53.015–71.866 | |

| Overall | 79 | 92.493 ± 12.453 | 81.897–141.847 | |

| Gini-Simpson index | Classified | 0.964 | 0.965 ± 0.002 | 0.964–0.968 |

| Sacred | 0.955 | 0.957 ± 0.003 | 0.955–0.962 | |

| Overall | 0.967 | 0.968 ± 0.001 | 0.967–0.970 |

Note: dConfidence limits: The estimated parameter values were considered to be significantly different if the 95% confidence limits did not overlap.

Table 2: Indicators of biodiversity appreciation among forests.

Figure 5: Evolution of species richness according to sample size among forests.

Conservation status of forests

Most of the inventoried species belong to the least concern class (83.97%) followed by vulnerable (13.21%), Endangered (2.39) and near threatened (0.43) classes. Khaya senengalensis (Miliaceae), Vitellaria paradoxa (Sapotaceae), Afzelia africana (Fabaceae) were identified as vulnerable species in both forests of Djougou district by referring to IUCN red list [23-25]. However, Pterocarpus erinaceus (Papilionoideae) is the only endangered species recorded in both type of forests while Garcinia sp. (Clusiaceae) was only endangered species reported from sacred forests (Table 3).

| Forest | Species | Family | Genus | IUCN Statut1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classified | Khaya senengalensis | Meliaceae | Khaya | VU |

| Pterocarpus erinaceus | Papilionoideae | Pterocarpus | EN | |

| Vitellaria paradoxa | Sapotaceae | Vitellaria | VU | |

| Afzelia africana | Fabaceae | Afzelia | VU | |

| Sacred | Khaya senengalensis | Meliaceae | Khaya | VU |

| Pterocarpus erinaceus | Papilionoideae | Pterocarpus | EN | |

| Vitellaria paradoxa | Sapotaceae | Vitellaria | VU | |

| Afzelia africana | Fabaceae | Afzelia | VU | |

| Garcinia sp. | Clusiaceae | Garcinia | EN |

Note: 1Vulnerable (VU); Endangered (EN)

Table 3: Species status among forests according to IUCN red list.

Taxonomic diversity and variation of species among forests

In the present study, the top 20 families of species inventoried in both forests were mainly Fabaceae, Sapotaceae, Combretaceae, Meliaceae, Anacardiaceae and Rubiaceae. These results corroborate with those of Neuenschwander, et al. which reported that the richest species in the flora of Benin belonged to Fabaceae family. Similarly, this family was the most representative in the Badenou classified forest in Ivory coast and in the Djoumouna forest in the republic of Congo. In overall, Fabaceae family is still the most common in tropical forests. Our results also reported numerous subfamilies including Caesalpinioideae, Mimisoideae and Papilionoideae, which enhanced the importance of Fabacea family. However, the abundance of Rubiaceae recorded from the different forests suggests that they did not yet reached climax status [26-30].

In fact, the taxonomic diversity reported in this study (73 species, 58 genera and 29 families) was much lower than that obtained by Gnahore, et al. in the periphery of the Banco National Park in Côte-d'Ivoire, and Miabangana in the Djoumouna forest in the Republic of Congo. This variation may be explained by the differences in ecological zones, the surface of sampled areas, the sampling methods and the number of sampling methods. According to Vroh, et al. the combination of several sampling methods provides a very important floristic richness.

The results pointed out Vitellaria paradoxa, Isoberlinia doka, Burkea africana, Isoberlinia tomentosa, Isoberlinia tomentosa, Terminalia leiocarpa, Khaya senengalensis, Azadirachta indica and Canthium hispidum as the most dominant species in the forests of Djougou district. These results are not uncommon and have been reported by Adomou characterizing the study area by open forests and wooded savannas with Isoberlinia doka and Vitellaria paradoxa. Our results indicated that Shannon's entropy values and Gini-Simpson indices differed significantly among forests. The values of these parameters were higher in classified forests suggesting a lower anthropization in these forests compared to sacred ones. In this study, the Shannon's entropy values obtained from both types of forests are in overall higher than those obtained by Kouadio, et al. However, the low species richness recorded from sacred forests differed from that reported in previous studies. These results may be attributed to the difference in vegetation structure and composition. For example, the sacred forests of Djougou, in Northwestern Benin are rich and more diversified in species than the sacred Badja forest in southwestern Benin [31-33]. This difference may result from the protection effort and the density of the population living alongside the sacred forest of Badja in southwestern Benin.

Conservation status of forests

Knowledge of special status species (threatened species and endemic species) is essential in determining the biodiversity status of specific area. These species are indicators for assessing the priority and the conservation status of forest. Our results showed that all inventoried species are listed in the IUCN red list. Accordingly, we found 3 vulnerable species (Khaya senegalensis, Vitellaria paradoxa and Afzelia africana) and 2 endangered species (Pterocarpus erinaceus and Garcinia sp.). Gnahore, et al. have pointed out that these species were all present in sacred forests and were the most vulnerable to anthropogenic pressures. However, the sacred forests of Djougou hosted Garcinia sp. which belongs to the Clusiaceae family. As a result, they were considered as high conservation values of category 1, 3 and 6. Therefore, policy documents for better conservation and sustainable management of these forests are needed.

In the present study, we assessed the biodiversity status in sacred and classified forests at Djougou district in Northwestern Benin. The results reported 76 species belonging to 58 genera and 27 families. The most abundant families were Fabaceae, Sapotaceae, Combretaceae, Meliaceae, Anacardiaceae and Rubiaceae. We also found a strong association of species families with forest types. Shannon's entropy values and Gini-Simpson indices differed significantly among forests. The diversity indices values were higher in classified forests than in sacred ones. All the inventoried species are in the threatened species category on the IUCN Red List, with 3 vulnerable species and 2 endangered ones. The forests of Djougou can be classified as high conservation values of category 1, 3 and 6. Therefore, strategic actions for sustainable conservation and management of these forests under anthropogenic pressures are needed.

The authors would like to thank Crepin T.S. ANIWANOU for his valuable comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

[Crossref]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref]

Citation: Alassane I, Akin YY, Kolawole MA, Ouinsavi CAIN (2023) What Does the Status of Forest Conservation Reveal about Biodiversity of Tropical Forest?. J For Res. 12: 474.

Received: 13-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. JFOR-23-21387; Editor assigned: 16-Jan-2023, Pre QC No. JFOR-23-21387 (PQ); Reviewed: 30-Jan-2023, QC No. JFOR-23-21387; Revised: 10-May-2023, Manuscript No. JFOR-23-21387 (R); Published: 17-May-2023 , DOI: 10.35248/2168-9776.23.12.474

Copyright: © 2023 Alassane I, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.