Journal of Women's Health Care

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0420

ISSN: 2167-0420

Research Article - (2021)

Introduction: In many developing countries, maternal mortality is still high. Although an effort has been made to achieve Millennium Development Goals, the positive results and significant decrease in maternal mortality is yet to come, especially in the sub-Saharan African countries. Ethiopia is a member of sub-Saharan countries with high maternal mortality. Since health education and promotion activities are insufficient, most births take place at home by non-health professionals and the public awareness in health facility delivery remains low. Because of these underlying factors, many Ethiopian women are dying from pregnancy and other pregnancy related causes. It is important to evaluate the women that deliver at health facilities versus the home.

Objective: To identify factors associated with health facility births in Ethiopia using demographic characteristics, pregnancy-related factors, and media-related factors and to know users of health facility births.

Method: This study used the data from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) 2011, which is a national representative sample data. This study analyzed specific health facility births. The demographic characteristics, pregnancy- related factors, and media-related factors were used as independent variables. Delivery places, the outcome variables were treated as categorical variables both bivariately and multivariately. A logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with delivery place.

Result: Maternal mortality in Ethiopian still high 676/100,000 per life births. Health facility births were still low. A total of 9,429 home deliveries and 1,467 health facility deliveries were identified from the EDHS 2011. Only 13.5% of pregnant women gave birth at a health facility. Women’s residence regions, residential place, educational level, wealth index, husband/partner education level, antenatal care visit and media exposure were significantly associated with their delivery place choice. Whereas older age, high number of parity and married women were negatively associated with health facility deliveries. The outcome of birth (child alive or not) had no association with delivery place selection.

Conclusion: This study verifies the factors associated with health facility births in Ethiopia. Region, place of residence, education level of pregnant women and partner and media exposure had significant association. To promote health facility utilization in birth and decrease maternal mortality special efforts will be needed taking account the significant factors. As a positive tool for breaking regional inequality and health education, media and social media may serve an important role in facilitating health facility births.

Delivery place, Home delivery, Health facility delivery, Maternal health

Ethiopia is one of the Africa’s oldest independent countries. Geographically, it is a land locked country and is bordered by six countries; Republic of Sudan, Republic of Southern Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia and Kenya. It is a country with great geographical diversity ranging from peaks up to 4550 meters above sea level to a depression of 110 meter below sea level. The climate varies with the topography, from as high as 47 degrees Celsius in the Affar depression to as low as 10 degrees Celsius in the highlands. There are three principal climates in Ethiopia: tropical rainy, dry, and warm temperate. Maximum and minimum average temperatures vary across regions and seasons of the year.

Ethiopia is one of the least urbanized countries in the world; only 16 percent of the population lives in the urban areas. The majority of the population lives in the highland areas. Christianity and Islam are the main religions; about half of the population are Orthodox Christians, one-third are Muslims, and about one in every five (18 percent) are Protestants.

Ethiopia is a mosaic of nationalities and more than 80 different languages are spoken. Its population is nearly 84 million with high dependency ratio cited from the projection of 2007 censes [1].

Despite major strides to improve the health of the population in the last two decades, Ethiopian’s population still faces high rate of morbidity and mortality, and the health status remains relatively poor. The major health problems of the country are largely preventable communicable diseases and nutritional disorders. More than 90% of the child deaths are due to pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, neonatal problems, malnutrition and HIV/AIDS, and often a combination of these conditions. Vital health indicators of infant mortality, under five mortality, and maternal mortalities are 58 per 1000 life birth, 88 per 1000 life birth and 676 death per 100,000 life birth respectively.

Ethiopia had no health policy until the early 1960s, when the health policy initiated by the World Health Organization (WHO) was adopted. In the mid-1970s, health policy was formulated with emphasis on disease prevention and control. The current health policy, promulgated by the transitional government, takes into account broader issues such as population dynamics, food availability, acceptable living conditions, and other essentials of better health in 1993.

Recently Ethiopian government developed a three tier health care delivery system. The primary health care unit has five health posts, one health centre and primary hospital for 1/5000, 1/25,000 and 1/100,000 population respectively, with each of health care units are linked by a referral system. The second tier general hospital which services 1-1.5 million populations and the third tier specialized hospitals which covers 3.5-5 million populations [1]. Since this plan started gradual health service utilization are seen in the country.

In 2003, the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) launched a new health care plan called health extension program, which is run by two female health extension worker (HEW) at grass root (Keeble) level to reach rural community since more than 85% of Ethiopian population live in rural area. It has 16 component of health care service at kebele level with participation of local community [2]. This program had significant success in terms of other activities like immunization, family planning, communicable disease control and health promotion and education. However in the case of attending deliveries at their health post and community level effects were non-significant. A study conducted in Tigray region of Ethiopian showed that health extension workers have poor knowledge and skills regarding attending deliveries at health posts or helping laboring mothers during home to home visits. Also poor referral linkage with the nearest health center to help laboring mother was seen [3]. Similarly a Nepalese government employs two cadres of health worker at village level to reduce maternal mortality in the country. However they are incapable of attending to delivery in their village [4].

Currently, the Ethiopian ministry of health is developing new policies for pregnant women. Every pregnant woman should have health care delivery access free of charge at all public health facility level. They also allocated ambulances for each district to bring labouring mothers from their home to health facility without any charge [5]. Even though the government invested all these resources, many women still did not give birth at health facilities. Health facility delivery coverage is still 10% [1]. Similarly; Senegalese government provided free health institution delivery in public health sector, but the improvement of health facility delivery saw little change (from 40 to 44%) [6].

Even though many efforts are made to reduce maternal mortality, maternal mortality is still high worldwide. Every day 800 women die from pregnancy and pregnancy related causes which are preventable and 99% of this death occurs in developing countries [7,8]. Almost half of maternal death occurs in sub-Saharan countries and one third occurs in south Asia. In Ethiopia about 676/100,000 women per total life births die from pregnancy related causes and delivery [1]. High maternal death reflects that the health care access and utilization by pregnant women in developing countries are still low and that there is a huge gap between developed and developing countries regarding the health care system. Most maternal mortalities are preventable when all births are attended by a skilled health professional at a health facilities. Majority of causes of maternal mortality are sever haemorrhages, sepsis, pre-eclampsia/ eclampsia and indirect causes of anaemia [9,10]. Non health facility birth may result in fistula and rupture of uterus. Such critical conditions may happen when deliveries are attended at homes by traditional birth attendants and other non-health professionals. A study conducted in Uganda show that Out of 14,656 deliveries, 73 cases of ruptured uterus were recorded [11] and a similar study conducted in Nigeria also show that from 4,361 delivery cases; 51 cases of uterine ruptured reported [12]. Such type of cases are early identifiable and managed at well-equipped health facility by adequately trained health professionals.

In developing countries, the rates of home deliveries are still high. Worldwide the proportion of home birth ranges from 14% in Nagpur, India to 74% in the Equateur Province of Democratic republic of Congo [13]. Usually home deliveries are attended by traditional birth attendants or relatives who give them psychological and social support for the laboring mother. Poor handling and supporting of laboring mothers at health facilities decreases the rate of health facility births. A study conducted in Tanzania and Iran show that most of the mothers are mistreated and did not get positive support from health professional during labor and delivery at health facility [14,15].

Health facility births in developing countries are affected by many factors associated with the pregnant mother. The percentage of women delivery at a health facility varies from 40.3% in Asia to 55.4% in Latin America due to pregnant mother related problems in using health facility as the delivery place [16]. A similar study conducted in Ethiopia, Oromia, Dodota district showed that out of the 506 respondents only 92(18.2%) gave birth to their last child at health facility [5]. Due to women’s educational and health awareness, majority of pregnant women in developing countries do not consider pregnancy as a risk. Every pregnant women should be ready for their pregnancy mentally, socially and economically to receive new baby in safe manner including selection of delivery location. A study in Nepal on birth preparedness reveal that women in early age and late age have good birth preparedness to deliver at health facility (56%) compared to the middle age [17].

Health facility delivery requires many physical and medical examinations during labor and delivery to identify the progress of labor. Most health centers and hospitals in developing countries do not have advanced medical technology. Due to lack of these modern technologies the progress of labor maybe only examined manually at health facility. Vaginal examination is one of manual examination procedure during labor. Frequent vaginal examination is one of the reasons for low health facility delivery [18]. Women’s beliefs and attitudes on health facility births are very low and nearly half of pregnant women did not know the importance of health facility delivery in developing countries [19].

In developing countries births are attended by traditional birth attendants, relatives or any person nearby during labor and delivery. Those people do not have any formal trained knowledge and skill on management of delivery. Place of births are not clean for conducting delivery. These expose mothers for sepsis (infection) after delivery during postpartum period. According to world health organization (WHO) recommendation deliveries should be attended by formal trained health professional (nurses, midwifes, and doctors) at health facility to save the life of mothers and new born (WHO 1996). In developing countries these recommendations are not fully applied due to shortage of medical health professional and health facilities. Nowadays different organization, nongovernmental organization (NGO) and host country governments are trying to work on maternal and child health to achieve millennium development goal (MDG). However some developing countries are not on the track to MDG due to political, social and economic condition of the countries, and still many women are dying from pregnancy and pregnancy related causes. To identify why women in developing countries do not like to deliver at health facility requires much investigation and research. There is no study conducted at national level to identify the reason why Ethiopian women do not like to give birth at health facilities. This study tries to come up with some of the factors that are associated with health facility birth by using Ethiopian demographic and health survey data 2011.

Objective: To identify determinant and factors associated with health facility births in Ethiopia using demographic characteristics, pregnancy-related factors and media related factors and to know users of health facility births in the country.

Study Population and Data Sources

This study used data from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) 2011, which is a nationally representative sample data. The 2011 EDHS was carried out under the ministry of health Ethiopia by central statistics agency (CSA) and ICF International through funding in USIAD. Permission to access and use the data was requested and obtained by an online application to the administrator of the database in USA. Details of information concerning the data can be obtained at the following web page: Measure Demographic Health Surveys.

The 2011 EDHS used the sampling frame provided by the list of census enumeration areas with population and household information from 2007 National population and Housing census. Administratively, region in Ethiopia are divided into zones, and zones into administrative units called “woreda”. Each woreda is further subdivided into lowest administrative unit called “kebele”.

During the 2007 census each kebele was subdivided into census enumeration areas (EAS). The 2011 EDHS sample was selected using, the two stage cluster design, and EAS were the sampling unit for the first stage. The sample included 624 EAS, 187 in urban areas and 437 in rural areas. Households comprise second stage of sampling. A complete listing of households was conducted in each of the EAS selected from September 2010 through January 2011. A representative sample 17,817 households were selected for 2011 EDHS. The individual women data was used for this study and all women age from 15-49 years were selected. From a total of 16,515 women, 10,896 were analyzed after excluding those without delivery experiences (n=5619).

Measurements and Variables

This study analyzed for specific health facility births. Women with any delivery experiences at any health facility where qualified health professionals were available were coded as one and women who had delivery experiences at home (out of health facilities) were coded as zero.

Delivery places, the outcome variable, were treated as categorical variables in both bivariate and multivariate analyses. The demographic characteristics (age, current marital status, region, residence place, educational level, husband/partner educational level, religion, and wealth index), pregnancy-related factor (number of parity, antenatal care, and outcome of birth (child alive or not)) and media-related factors (newspaper or magazine reading, radio listening and watching television) were used as independent variables.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed to describe the number and the percentage of respondents according to demographic characteristics, pregnancy-related factor and media-related for all women in the study. To identify the association between the dependent variable delivery places and the independent variables, bivariate analyses were conducted using chi squared test and logistic regression analysis were run for each independent variable. Value of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association between the places of delivery and demographic-related factors, pregnancyrelated factors and media-related factors. Odds ratios and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. To explore candidate variables in our final model, we used stepwise procedure in the logistic regression analysis. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

A total of 9,429 homes and 1,467 health facility deliveries were identified from EDHS 2011. Women’s average age was 31.73 years old with a standard deviation of +8 years old. The highest proportions of women were in the age distributions 25-29 (24.5%). During the time of the survey, 79.1% of women were married and 0.94% women were unmarried but had delivery experiences (Table 1).

| Variable | Frequency | Percent (%) | Cumulative frequency | Cumulative percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery place | ||||

| Home | 9,429 | 86.54 | 9,429 | 86.54 |

| Health Facility | 1,467 | 13.46 | 10,896 | 100.00 |

| Age in 5-year groups | ||||

| 15-19 | 421 | 3.86 | 421 | 3.86 |

| 20-24 | 1,674 | 15.36 | 2,095 | 19.23 |

| 25-29 | 2,665 | 24.46 | 4,760 | 43.69 |

| 30-34 | 1,937 | 17.78 | 6,697 | 61.46 |

| 35-39 | 1,860 | 17.07 | 8,557 | 78.53 |

| 40-44 | 1,274 | 11.69 | 9,831 | 90.23 |

| 45-49 | 1,065 | 9.77 | 10,896 | 100.00 |

| Current marital status | ||||

| Not married | 102 | 0.94 | 102 | 0.94 |

| Married | 8,621 | 79.12 | 8,723 | 80.06 |

| Divorced | 588 | 5.4 | 9,311 | 85.45 |

| Widowed | 561 | 5.15 | 9,872 | 90.6 |

| Separated | 716 | 6.57 | 10,588 | 97.17 |

| Not live together | 308 | 2.83 | 10,896 | 100.00 |

| Region | ||||

| Tigray | 1,173 | 10.77 | 1,173 | 10.77 |

| Afar | 944 | 8.66 | 2,117 | 19.43 |

| Ahmara | 1,415 | 12.99 | 3,532 | 32.42 |

| Oromia | 1,469 | 13.48 | 5,001 | 45.9 |

| Somali | 678 | 6.22 | 5,679 | 52.12 |

| Benishangul Gumuz | 916 | 8.41 | 6,595 | 60.53 |

| SNNP | 1,358 | 12.46 | 7,953 | 72.99 |

| Gambela | 832 | 7.64 | 8,785 | 80.63 |

| Harari | 695 | 6.38 | 9,480 | 87 |

| Addis Ababa(capital) | 746 | 6.85 | 10,226 | 93.85 |

| Dire Dawa | 670 | 6.15 | 10,896 | 100.00 |

| Type of residential place | ||||

| Urban | 2,767 | 25.39 | 2,767 | 25.39 |

| Rural | 8,129 | 74.61 | 10,896 | 100.00 |

| Respondents’ highest educational level | ||||

| No education | 7,166 | 65.77 | 7,166 | 65.77 |

| Primary | 2,849 | 26.15 | 10,015 | 91.91 |

| Secondary | 556 | 5.10 | 10,571 | 97.02 |

| Higher level | 325 | 2.98 | 10,896 | 100.00 |

| Husband/partner's educational level | ||||

| No education | 5,407 | 50.86 | 5,407 | 50.86 |

| Primary | 3,632 | 34.16 | 9,039 | 85.02 |

| Secondary | 969 | 9.11 | 10,008 | 94.14 |

| Higher level | 623 | 5.86 | 10,631 | 100.00 |

| Religion | ||||

| Orthodox | 4,355 | 40.69 | 4,355 | 40.69 |

| protestant | 1,975 | 18.45 | 6,330 | 59.14 |

| Muslim | 4,374 | 40.86 | 10,704 | 100.00 |

| Wealth index | ||||

| Poorest | 2,882 | 26.45 | 2,882 | 26.45 |

| Poor | 1,761 | 16.16 | 4,643 | 42.61 |

| Middle | 1,637 | 15.02 | 6,280 | 57.64 |

| Rich | 1,663 | 15.26 | 7,943 | 72.9 |

| Richest | 2,953 | 27.10 | 10,896 | 100.00 |

| Current working status | ||||

| Not Working | 6,986 | 64.19 | 6,986 | 64.19 |

| Working | 3,898 | 35.81 | 10,884 | 100.00 |

| Number of parity | ||||

| 0-2 | 3,823 | 35.09 | 3,823 | 35.09 |

| 3-4 | 1,434 | 13.16 | 5,257 | 48.25 |

| 5-6 | 2,409 | 22.11 | 7,666 | 70.36 |

| 7+ | 3,230 | 29.64 | 10,896 | 100.00 |

| No of antenatal visit during pregnancy | ||||

| 0 | 4,266 | 55.14 | 4,266 | 55.14 |

| 1 | 338 | 4.37 | 4,604 | 59.51 |

| 2 | 527 | 6.81 | 5,131 | 66.32 |

| 3 | 901 | 11.65 | 6,032 | 77.96 |

| 4+ | 1,705 | 22.04 | 7,737 | 100.00 |

| Ever had child born dead | ||||

| Yes | 154 | 1.41 | 154 | 1.41 |

| No | 10,742 | 98.59 | 10,896 | 100.00 |

| Frequency of reading newspaper or magazine | ||||

| Does not read | 9,621 | 88.4 | 9,621 | 88.4 |

| Read once a week | 976 | 8.97 | 10,597 | 97.36 |

| Frequency of listening to radio | ||||

| Does not Listen | 5,764 | 52.93 | 5,764 | 52.93 |

| Listen once a week | 3,127 | 28.71 | 8,891 | 81.64 |

| Listen more than once a week | 1,999 | 18.36 | 10,890 | 100.00 |

| Frequency of watching television | ||||

| Does not watch | 6,835 | 62.79 | 6,835 | 62.79 |

| Watch once a week | 2,283 | 20.97 | 9,118 | 83.77 |

| Watch more than once a week | 1,767 | 16.23 | 10,885 | 100.00 |

Table 1. General characteristics of study participants.

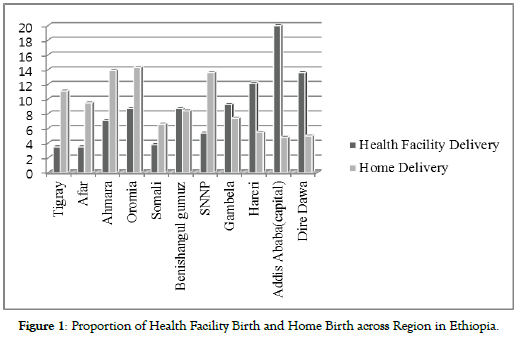

The proportion of women across regions were as follows: Tigray (10.77%), Afar (8.66%), Ahmara (12.99%), Oromia (13.48%), Somalia (6.22%), Benishangul Gumuz (8.41%), South nation and nationalities peoples (SNNP) (12.46%), Gambela (7.64), Harari (6.38%), Addis Ababa (Capital) (6.85%) and Dire Dawa (6.15%). Also the proportion of women who live in the two cities Administration, Addis Ababa (capital) and Dire Dawa, were 6.9% and 6.2% respectively. The proportions of home delivery were highest in Oromia (14.3%) and lowest in Addis Ababa (capital) (4.8%). Figure 1 shows the regional proportion of health facility and home deliveries in the country. The majority of women (74.6%) live in the rural part of the countries (Table 1).

Figure 1. Proportion of Health Facility Birth and Home Birth across Region in Ethiopia.

The literacy level of women who participated in this study was as follows: non-educated (65.8%), primary education (26.2%), secondary education (5.1%) and higher level education (2.9%). Half of the women were married to uneducated men (50.9%) and 5.9% were married to high level educated men. In this study the distribution of orthodox (40.7%) and Muslim (40.9%) religions were nearly equal and were followed by protestant (18.5%). The socioeconomic distribution across the country was as follows: poorest (26.5%), poor (16.2%), middle (15.0%), rich (16.2%) and richest (27.1%). During the time of the survey, 64.2% of the women were not working (Table 1).

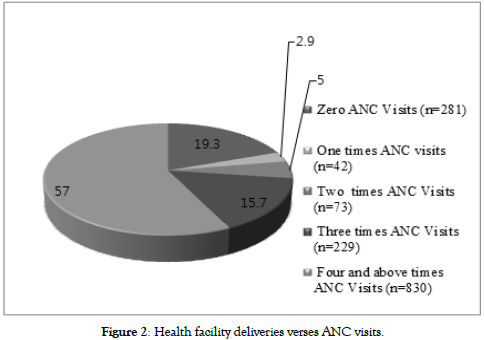

Regarding to maternal parities, 35.1% of women had two and fewer delivery experiences while 29.6% had four or more times. More than half of women (55.1%) did not have any ANC visits during pregnancy and 22.0% of women had four or more times ANC visits. Most women who visited ANC during their pregnancy time gave birth at health facility (Figure 2). During the time of the survey 98.6% of the women had no child born death.

Figure 2. Health facility deliveries verses ANC visits.

As for media exposure, 88.4% of women did not read any newspaper or magazines in a week while only 2.6% of women read more than once in a week. Greater than half, 52.9% of women, did not listen to any information through radio and 62.8% of women never watched television.

Health facility deliveries were varied across regions in Ethiopia. Women living in Addis Ababa had the highest proportion of health facility births (39.4%) however women living in Afar region had the lowest proportion of health facility births (5.4%). In this study women living in Gambela region had the highest child birth experience at their early age (15-19) (6.3%) while it was lowest experience in Addis Ababa (0.5%). Having children before marriage were highest in Addis Ababa (4.7%) and zero in Somalia region. Most women were living in the rural part of the country. Women living in rural area were highest in Ahmara region (90.0%) (Table 2).

| Variable | Tigray N (%) | Afar N (%) | Ahmara N (%) | Oromia N (%) | Somalia N (%) | Benisangu N (%) | SNNP N (%) | Gambela N (%) | Hareri N (%) | A/Ababa N (%) | Dire Dawa N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place of delivery | |||||||||||

| Health facility | 115 (9.8) | 51 (5.4) | 104 (7.4) | 127 (8.7) | 56 (8.4) | 128 (13.9) | 79 (5.8) | 137 (16.5) | 177 (25.5) | 294 (39.4) | 199 (29.7) |

| Home births | 1058 (90.2) | 893 (94.6) | 1311 (92.7) | 1342 (91.4) | 622 (91.7) | 788 (86.0) | 1279 (94.2) | 695 (83.5) | 518 (74.5) | 452 (60.6) | 471 (70.3) |

| Age in 5- year groups | |||||||||||

| 15-19 | 51 (4.4) | 32 (3.4) | 59 (4.5) | 69 (4.7) | 27 (3.9) | 52 (5.7) | 25 (1.8) | 52 (6.3) | 31 (4.5) | 4 (0.5) | 19 (2.8) |

| 20-24 | 196 (16.7) | 175 (18.5) | 214 (15.1) | 227 (15.5) | 103 (15.2) | 157 (17.1) | 176 (12.9) | 145 (17.4) | 108 (15.5) | 82 (10.9) | 91 (13.6) |

| 25-29 | 239 (20.6) | 241 (25.5) | 297 (20.9) | 399 (27.2) | 160 (23.6) | 231 (25.2) | 329 (24.2) | 202 (24.3) | 184 (26.5) | 201 (26.9) | 182 (27.2) |

| 30-34 | 184 (15.7) | 144 (15.3) | 240 (16.9) | 246 (16.6) | 126 (18.6) | 157 (17.1) | 268 (19.6) | 149 (17.9) | 117 (16.8) | 175 (23.5) | 131 (19.6) |

| 35-39 | 227 (19.4) | 149 (15.8) | 142 (17.1) | 229 (15.6) | 126 (18.6) | 141 (15.4) | 241 (17.6) | 125 (15.0) | 111 (15.8) | 137 (18.4) | 132 (19.7) |

| 40-44 | 150 (12.8) | 130 (13.8) | 169 (11.9) | 150 (10.2) | 89 (13.1) | 106 (11.6) | 168 (12.47) | 88 (10.6) | 76 (10.9) | 78 (10.5) | 70 (10.5) |

| 45-49 | 126 (10.7) | 73 (7.7) | 194 (13.7) | 149 (10.1) | 47 (6.9) | 72 (7.9) | 151 (11.1) | 71 (8.5) | 68 (9.8) | 69 (9.3) | 45 (6.7) |

| Current marital status | |||||||||||

| Not married | 12 (1.0) | 3 (0.3) | 15 (1.1) | 7 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 6 (0.4) | 15 (1.8) | 5 (0.7) | 35 (4.7) | 2 (0.3) |

| Married | 866 (73.8) | 839 (88.9) | 1151 (81.3) | 1251 (85.2) | 599 (88.4) | 804 (87.8) | 1040 (76.6) | 593 (71.3) | 525 (75.5) | 473 (63.4) | 480 (71.6) |

| Divorced | 21 (1.8) | 3 (0.3) | 31 (2.2) | 49 (3.3) | 13 (1.9) | 19 (2.1) | 176 (12.9) | 84 (10.1) | 49 (7.1) | 62 (8.3) | 81 (12.1) |

| Widowed | 76 (6.5) | 40 (4.2) | 55 (3.9) | 76 (5.2) | 23 (3.4) | 26 (2.5) | 65 (4.8) | 64 (7.7) | 38 (5.5) | 65 (8.7) | 33 (4.9) |

| Separated | 167 (14.2) | 54 (5.7) | 135 (9.5) | 58 (3.9) | 37 (5.5) | 46 (5.0) | 37 (2.7) | 38 (4.6) | 51 (7.3) | 53 (7.1) | 40 (5.9) |

| Not live together | 31 (2.6) | 5 (0.5) | 28 (1.9) | 28 (1.9) | 6 (0.9) | 19 (2.1) | 34 (2.5) | 38 (4.6) | 27 (3.9) | 58 (7.8) | 34 (5.1) |

| Type of Residential Place | |||||||||||

| Urban | 215 (18.3) | 157 (16.6) | 141 (9.9) | 205 (13.9) | 198 (29.2) | 105 (11.5) | 117 (8.6) | 140 (16.8) | 355 (51.1) | 746 (100.0) | 388 (57.9) |

| Rural | 958 (81.7) | 787 (83.4) | 1274 (90.0) | 1264 (86.0) | 480 (70.8) | 811 (88.5) | 1241 (91.4) | 692 (83.2) | 340 (48.9) | 0 (0.0) | 282 (42.1) |

| Respondents’ highest educational level | |||||||||||

| No education | 791 (67.4) | 835 (88.5) | 1,157 (81.8) | 947 (64.5) | 579 (85.4) | 675 (73.5) | 877 (64.6) | 405 (48.7) | 336 (48.4) | 172 (23.1) | 392 (58.5) |

| Primary | 310 (26.4) | 77 (8.2) | 217 (15.3) | 443 (30.2) | 85(12.5) | 209 (22.8) | 431 (31.7) | 366 (43.9) | 215 (30.9) | 308 (41.3) | 188 (28.1) |

| Secondary | 50 (4.3) | 22 (2.3) | 21 (1.5) | 42 (2.9) | 12 (1.8) | 15 (1.6) | 25 (1.8) | 35 (4.2) | 93 (13.4) | 172 (23.1) | 69 (10.3) |

| Higher level | 22 (1.9) | 10 (1.1) | 20 (1.4) | 37 (2.5) | 2 (0.3) | 17 (1.9) | 25 (1.8) | 26 (3.1) | 51 (7.3) | 94 (12.6) | 21 (3.1) |

| Husband/partner's educational level | |||||||||||

| No education | 620(54.3) | 743 (78.4) | 1,007 (73.0) | 663 (45.7) | 454 (69.6) | 526 (58.4) | 544 (40.6) | 278 (34.3) | 233 (34.9) | 98 (14.0) | 250 (38.2) |

| Primary | 407 (35.7) | 134 (14.3) | 309 (22.4) | 609 (44.1) | 137 (21.0) | 315 (35.0) | 666 (49.7) | 298 (36.8) | 229 (34.3) | 269 (38.5) | 228 (34.8) |

| Secondary | 66 (5.8) | 47 (5.0) | 31 (2.3) | 85 (5.7) | 44 (6.7) | 34 (3.8) | 77 (5.8) | 138 (17.0) | 121 (18.1) | 198 (28.3) | 128 (19.5) |

| Higher level | 48 (4.21) | 21 (2.24) | 32 (2.32) | 62 (4.28) | 17 (2.61) | 25 (2.78) | 53 (3.96) | 96 (11.85) | 85 (12.72) | 135 (19.29) | 49 (7.48) |

| Religion | |||||||||||

| Orthodox | 1,112 (94.8) | 57 (6.0) | 1,166 (82.4) | 391 (27.1) | 23 (3.4) | 278 (30.6) | 325 (24.3) | 221 (27.0) | 181 (26.2) | 557 (74.7) | 160 (23.9) |

| protestant | 1 (0.1) | 16 (1.7) | 3 (0.2) | 328 (22.7) | 1 (0.25) | 137 (15.1) | 847 (63.4) | 543 (66.4) | 23 (3.3) | 58 (7.8) | 18 (2.7) |

| Muslim | 60 (5.1) | 870 (92.3) | 246 (17.4) | 723 (50.1) | 651 (96.4) | 494 (54.4) | 165 (12.3) | 54 (6.6) | 488 (70.5) | 131 (17.6) | 492 (73.4) |

| Wealth index | |||||||||||

| Poorest | 308 (26.3) | 599 (63.5) | 319 (22.5) | 257 (17.5) | 300 (44.3) | 273 (29.8) | 349 (3.2) | 396 (3.6) | 14 (0.1) | 3 (0.0) | 64 (0.6) |

| Poor | 257 (21.9) | 96 (10.2) | 359 (25.4) | 314 (21.4) | 67 (9.9) | 180 (19.7) | 282 (20.8) | 82 (9.9) | 42 (6.0) | 2 (0.3) | 80 (11.9) |

| Middle | 197 (16.8) | 46 (4.9) | 331 (23.4) | 306 (20.8) | 56 (8.3) | 181 (19.8) | 284 (20.9) | 84 (10.1) | 65 (9.4) | 1 (0.1) | 86 (12.8) |

| Rich | 154 (13.1) | 52 (5.5) | 256 (18.1) | 326 (22.2) | 86 (12.7) | 189 (20.6) | 268 (19.7) | 142 (17.1) | 148 (21.3) | 3 (0.4) | 39 (5.8) |

| Richest | 257 (21.9) | 151 (16.0) | 150 (10.6) | 266 (18.1) | 169 (24.9) | 93 (10.2) | 175 (12.9) | 128 (15.4) | 426 (61.3) | 737 (98.8) | 401 (59.9) |

| Current working status | |||||||||||

| Not Working | 814 (69.4) | 800 (84.9) | 985 (69.7) | 869 (59.2) | 546 (81.0) | 524 (57.3) | 803 (59.1) | 503 (60.5) | 389 (56.1) | 348 (45.7) | 405 (60.5) |

| Working | 359 (30.6) | 142 (15.1) | 429 (30.3) | 599 (40.8) | 128 (18.9) | 390 (42.7) | 554 (40.8) | 329 (39.5) | 305 (43.9) | 398 (53.3) | 265 (39.5) |

| Number of parity | |||||||||||

| 0-2 | 401 (34.2) | 291 (30.8) | 462 (32.7) | 450 (30.6) | 146 (21.5) | 286 (31.2) | 357 (26.3) | 323 (38.8) | 319 (45.9) | 499 (66.9) | 289 (43.1) |

| 3-4 | 276 (23.5) | 239 (25.3) | 343 (24.2) | 397 (27.0) | 162 (23.9) | 237 (25.9) | 322 (23.7) | 233 (28.0) | 180 (25.9) | 166 (22.3) | 189 (28.2) |

| 5-6 | 247 (21.1) | 173 (18.3) | 272 (19.2) | 279 (18.9) | 145 (21.4) | 213 (23.3) | 304 (22.4) | 166 (19.9) | 96 (13.8) | 55 (7.4) | 108 (16.1) |

| 7+ | 249 (21.2) | 241 (25.5) | 338 (23.9) | 343 (23.4) | 225 (33.2) | 180 (19.7) | 375 (27.6) | 110 (13.2) | 100 (14.4) | 26 (3.5) | 84 (12.5) |

| No of antenatal visit during pregnancy | |||||||||||

| 0 | 301 (35.6) | 509 (71.4) | 594 (61.9) | 662 (60.2) | 416 (74.4) | 417 (62.2) | 632 (60.1) | 341 (56.4) | 181 (41.2) | 21 (6.1) | 192 (42.6) |

| 1 | 59 (6.9) | 35 (4.9) | 77 (8.0) | 32 (2.9) | 22 (3.9) | 25 (3.7) | 33 (3.1) | 30 (4.9) | 7 (1.6) | 2 (0.6) | 16 (3.5) |

| 2 | 82 (9.7) | 51 (7.1) | 64 (6.7) | 62 (5.6) | 25 (4.5) | 51 (7.6) | 83 (7.9) | 36 (5.9) | 42 (9.6) | 3 (0.9) | 28 (6.2) |

| 3 | 152 (9.7) | 58 (7.2) | 110 (6.7) | 138 (5.6) | 54 (4.5) | 76 (7.6) | 122 (11.6) | 61 (10.1) | 58 (13.2) | 19 (5.5) | 53 (11.7) |

| 4+ | 252 (29.8) | 60 (8.4) | 114 (11.9) | 206 (18.7) | 42 (7.5) | 101 (15.1) | 181 (17.2) | 137 (22.6) | 151 (34.4) | 299 (86.9) | 162 (35.9) |

| Ever had child born dead | |||||||||||

| Yes | 14 (1.2) | 14 (1.5) | 22 (1.6) | 14 (0.9) | 11 (1.6) | 20 (2.2) | 10 (0.7) | 18 (2.2) | 13 (1.9) | 11 (1.5) | 5 (0.8) |

| No | 1,159 (98.8) | 930 (98.5) | 1,393 (98.4) | 1,455 (99.1) | 667 (98.4) | 896 (97.8) | 1,348 (99.3) | 814 (97.8) | 682 (98.1) | 735 (98.5) | 665 (99.2) |

| Frequency of reading newspaper or magazine | |||||||||||

| Does not read | 1,038 (88.6) | 887 (93.9) | 1,336 (94.6) | 1,308 (96.0) | 652 (96.3) | 866 (94.7) | 1265 (93.3) | 760 (91.6) | 545 (78.4) | 414 (55.5) | 550 (82.3) |

| Read once a week | 108 (9.2) | 47 (4.9) | 68 (4.8) | 130 (8.9) | 22 (3.3) | 42 (4.6) | 73 (5.4) | 60 (7.2) | 108 (15.5) | 238 (31.9) | 80 (11.9) |

| Read more than once a week | 26 (2.2) | 10 (1.1) | 9 (0.6) | 31 (2.1) | 3 (0.4) | 6 (0.7) | 18 (1.3) | 10 (1.2) | 42 (6.0) | 94 (12.6) | 38 (5.7) |

| Frequency of listening to radio | |||||||||||

| Does not listen | 599 (51.1) | 575 (60.9) | 834 (58.9) | 571 (38.9) | 426 (62.8) | 604 (65.9) | 768 (56.6) | 632 (76.1) | 270 (38.9) | 118 (15.8) | 367 (54.8) |

| Listen once a week | 342 (29.2) | 254 (26.9) | 368 (26.0) | 582 (39.7) | 185 (27.3) | 195 (21.3) | 371 (27.3) | 158 (19.0) | 217 (31.3) | 312 (41.8) | 143 (21.3) |

| Listen more than once a week | 232 (19.8) | 115 (12.2) | 212 (14.9) | 314 (21.4) | 67 (9.9) | 117 (12.8) | 218 (16.1) | 41 (4.9) | 207 (29.8) | 316 (42.4) | 160 (23.9) |

| Frequency of watching to television | |||||||||||

| Does not watch | 692 (59.2) | 757 (80.3) | 1,047 (74.1) | 895 (61.0) | 573 (84.5) | 764 (83.4) | 843 (62.1) | 634 (76.2) | 218 (31.4) | 74 (9.9) | 338 (50.6) |

| Watch once a week | 328 (28.0) | 93 (9.9) | 277 (19.6) | 434 (29.6) | 64 (9.4) | 101 (11.0) | 347 (25.6) | 144 (17.3) | 160 (23.1) | 247 (33.2) | 88 (13.2) |

| Watch more than once a week | 150 (12.8) | 93 (9.9) | 90 (6.4) | 138 (9.4) | 41 (6.1) | 51 (5.6) | 168 (12.4) | 54 (6.5) | 316 (45.5) | 424 (56.9) | 242 (36.2) |

Table 2. Factors associated with health facility delivery in Ethiopia across region.

In Ethiopia women’s educational coverage is very low. Most uneducated women were living in Afar region (88.5%) while in Addis Ababa only 23.1% of women were uneducated. According to this study result the poorest women lives in Afar (63.5%) region and the richest women lives in Addis Ababa (98.8%). A small number of working women live in Afar region (15.1%) during the survey time whereas highest in Addis Ababa (53.4%) (Table 2).

The highest parity (7+) women live in Somalia region (33.2%) and women living in Addis Ababa had lowest parity (3.5%). Women living in Somalia region (74.4%) were not visit health center for ANC however; women living in Addis Ababa (86.9%) were had ANC visit during their pregnancy time. Most women living in Addis Ababa had media exposure while women living in the Somalia region had low media exposure (Table 2).

Factors Associated with Health Facility Births

Delivery place choice was significantly associated with demographicrelated factors, pregnancy-related factors and media related factors. Its association was checked with all variables used in this study by chi-square test (Table 3).

| Variables | Health facility birth N (%) | Home delivery N (%) | Total N (%) |

X2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in 5- year groups | 452.7 | <.0001 | |||

| 15-19 | 71 (4.8) | 350 (3.7) | 421 (3.9) | ||

| 20-24 | 383 (26.1) | 1,291 (13.7) | 1,674 (15.4) | ||

| 25-29 | 504 (34.4) | 2,161 (22.9) | 2,665 (24.5) | ||

| 30-34 | 267 (18.2) | 1,670 (17.7) | 1,937 (17.8) | ||

| 35-39 | 173 (11.8) | 1,687 (17.9) | 1,860 (17.1) | ||

| 40-44 | 53 (3.6) | 1,221 (12.9) | 1,274 (11.7) | ||

| 45-49 | 16 (1.1) | 1,049 (11.1) | 1,065 (9.8) | ||

| Current marital status | 128.3 | <.0001 | |||

| Not married | 30 (2.0) | 72 (0.8) | 102 (0.9) | ||

| Married | 1,142 (77.9) | 7,479 (79.3) | 8,621 (79.1) | ||

| Divorced | 142 (9.7) | 446 (4.7) | 588 (5.4) | ||

| Widowed | 28 (1.9) | 533 (5.7) | 561 (5.2) | ||

| Separated | 70 (3.8) | 646 (6.9) | 716 (6.6) | ||

| Not live together | 55 (3.8) | 253 (2.7) | 308 (2.8) | ||

| Region | 899.9 | <.0001 | |||

| Tigray | 115 (3.5) | 1,058 (11.1) | 1,173 (10.8) | ||

| Afar | 51 (3.5) | 893 (9.5) | 944 (8.7) | ||

| Ahmara | 104 (7.1) | 1,311 (13.9) | 1,415 (12.9) | ||

| Oromia | 127 (8.7) | 1,342 (14.3) | 1,469 (13.5) | ||

| Somali | 56 (3.8) | 622 (6.6) | 678 (6.2) | ||

| Benishangul Gumuz | 128 (8.7) | 788 (8.4) | 916 (8.4) | ||

| SNNP | 79 (5.4) | 1,279 (13.6) | 1,358 (12.5) | ||

| Gambela | 137 (9.3) | 695 (7.4) | 832 (6.4) | ||

| Harari | 177 (12.1) | 518 (5.5) | 695 (6.4) | ||

| AddisAbaba(capital) | 294 (20.0) | 452 (4.8) | 746 (6.9) | ||

| Dire Dawa | 199 (13.6) | 471 (5.0) | 670 (6.2) | ||

| Type of Residential Place | 1539.3 | <.0001 | |||

| Urban | 981 (66.9) | 1,786 (18.9) | 2,767 (25.4) | ||

| Rural | 486 (33.1) | 7,643 (81.1) | 8,129 (74.6) | ||

| Respondents’ highest educational level | 1098.5 | <.0001 | |||

| No education | 502 (43.2) | 6,664 (70.7) | 7,166 (65.8) | ||

| Primary | 572 (38.9) | 2,277 (24.2) | 2,849 (26.2) | ||

| Secondary | 242 (16.5) | 314 (3.3) | 556 (5.1) | ||

| Higher level | 151 (10.3) | 174 (1.9) | 325 (2.9) | ||

| Husband/partner's educational level | 1009.2 | <.0001 | |||

| No education | 285 (20.1) | 5,122 (55.6) | 5,407 (50.9) | ||

| Primary | 565 (39.9) | 3,067 (33.3) | 3,632 (34.2) | ||

| Secondary | 330 (23.3) | 639 (6.9) | 969 (9.1) | ||

| Higher level | 237 (16.7) | 386 (4.2) | 623 (5.9) | ||

| Religion | 56.5 | <.0001 | |||

| Orthodox | 726 (49.9) | 3,629 (39.2) | 4,355 (40.7) | ||

| protestant | 216 (14.9) | 1,759 (19.0) | 1,975 (18.5) | ||

| Muslim | 511 (35.2) | 3,863 (41.8) | 4,374 (40.9) | ||

| Wealth index | 1445.9 | <.0001 | |||

| Poorest | 167 (11.4) | 2,715 (28.8) | 2,882 (26.5) | ||

| Poor | 86 (5.9) | 1,675 (17.8) | 1,761 (16.2) | ||

| Middle | 76 (5.2) | 1,561 (16.6) | 1,637 (15.0) | ||

| Rich | 141 (9.6) | 1,522 (16.1) | 1,663 (15.3) | ||

| Richest | 997 (67.9) | 1,956 (20.7) | 2,953 (27.1) | ||

| Current working status | 27.9 | <.0001 | |||

| Not Working | 850 (58.0) | 6,136 (65.1) | 6,986 (64.2) | ||

| Working | 615 (41.9) | 3,283 (34.9) | 3,898 (35.8) | ||

| Number of parity | 587.9 | <.0001 | |||

| 0-2 | 910 (62.0) | 2,913 (30.9) | 3823 (35.1) | ||

| 3-4 | 192 (13.1) | 1,242 (13.2) | 1,434 (13.2) | ||

| 5-6 | 206 (14.0) | 2,203 (23.4) | 2,409 (22.1) | ||

| 7+ | 159 (10.8) | 3,071 (32.6) | 3,230 (29.6) | ||

| No of antenatal visit during pregnancy | 1456.9 | <.0001 |

|||

| 0 | 281 (19.3) | 3,985 (63.4) | 4,266 (55.1) | ||

| 1 | 42 (2.9) | 296 (4.7) | 338 (4.4) | ||

| 2 | 73 (5.0) | 454 (7.2) | 527 (6.8) | ||

| 3 | 229 (15.7) | 672 (10.7) | 901 (11.7) | ||

| 4+ | 830 (57.0) | 875 (13.9) | 1,705 (22.0) | ||

| Ever had child born dead | 6.4 | 0.0147 | |||

| Yes | 31 (2.1) | 123 (1.3) | 154 (1.4) | ||

| No | 1,436 (97.9) | 9,306 (98.7) | 1,0742 (98.6) | ||

| Frequency of reading newspaper or magazine | 574.6 | <.0001 | |||

| Does not read | 1,025 (69.9) | 8,596 (91.3) | 9,621 (88.4) | ||

| Read once a week | 321 (21.9) | 655 (6.9) | 976 (8.9) | ||

| Read more than once a week | 119 (8.1) | 168 (1.8) | 287 (2.6) | ||

| Frequency of listening to radio | 254.0 | <.0001 | |||

| Does not Listen | 538 (36.7) | 5,226 (55.5) | 5,764 (52.9) | ||

| Listen once a week | 464 (31.6) | 2,663 (28.3) | 3,127 (28.7) | ||

| Listen more than once a week | 465 (31.7) | 1,534 (16.3) | 1,999 (18.4) | ||

| Frequency of watching to television | 1096.5 | <.0001 | |||

| Does not watch | 467 (23.7) | 6,368 (67.6) | 6,835 (62.8) | ||

| Watch once a week | 347 (23.7) | 1,936 (20.6) | 2,283 (20.9) | ||

| Watch more than once a week | 652 (44.5) | 1,115 (11.8) | 1,767 (16.2) |

Table 3. Factors Associated with Health Facility Birth in Ethiopia.

Oldest age, married women, and high maternal parity had negative associations with health facility delivery. The youngest women (15- 19 years old) were 13.30 times more likely to deliver at a health facility (OR=13.30, 95% CI, 7.63-23.18) (Table 4).

| Variables | N | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in 5 year group | |||

| 15-19 | 421 | 13.30 (7.63-23.18) | <.0001 |

| 20-24 | 1,674 | 19.45 (11.72-32.28) | <.0001 |

| 25-29 | 2,665 | 15.29 (9.25-25.29) | <.0001 |

| 30-34 | 1,937 | 10.48 (6.29-17.46) | <.0001 |

| 35-39 | 1,860 | 6.72 (4.01-11.29) | <.0001 |

| 40-44 | 1,274 | 2.85 (1.62-5.01) | 0.0003 |

| 45-49 | 1,065 | 1.00 | |

| Current marital status | |||

| Not married | 102 | 1.00 | |

| Married | 8,621 | 0.37 (0.24-0.56) | <.0001 |

| Divorced | 588 | 0.76 (0.48-1.22) | 0.2576 |

| Widowed | 561 | 0.13 (0.07-0.22) | <.0001 |

| Separated | 716 | 0.26 (0.16-0.43) | <.0001 |

| Not live together | 308 | 0.52 (0.31-0.87) | 0.0135 |

| Region | |||

| Afar | 944 | 1.00 | |

| Tigray | 1,173 | 1.90 (1.35-2.68) | 0.0002 |

| Ahmara | 1,415 | 1.39 (0.98-1.96) | 0.0629 |

| Oromia | 1,469 | 1.66 (1.18-2.32) | 0.0032 |

| Somali | 678 | 1.58 (1.06-2.33) | 0.0234 |

| Benishangul Gumuz | 916 | 2.84 (2.03-3.99) | <.0001 |

| SNNP | 1,358 | 1.08 (0.75-1.55) | 0.6726 |

| Gambela | 832 | 3.45 (2.46-4.83) | <.0001 |

| Harari | 695 | 5.98 (4.3-8.32) | <.0001 |

| Addis Ababa(capital) | 746 | 11.38 (8.28-15.64) | <.0001 |

| Dire Dawa | 670 | 7.39 (5.33-10.26) | <.0001 |

| Type of residential place | |||

| Urban Rural |

2,767 | 1.00 | |

| 8,129 | 0.12(0.10-0.13) | <.0001 | |

| Respondents’ highest educational level | |||

| No education | 7,166 | 1.00 | |

| Primary | 2,849 | 3.34 (2.93-3.79) | <.0001 |

| Secondary | 556 | 10.23 (8.46-12.38) | <.0001 |

| Higher level | 325 | 11.52 (9.09-14.59) | <.0001 |

| Husband/partner's education level | |||

| No education | 5,407 | 1.00 | |

| Primary | 3,632 | 3.31 (2.85-3.84) | <.0001 |

| Secondary | 969 | 9.28 (7.76-11.09) | <.0001 |

| Higher level | 623 | 11.04 (9.03-13-49) | <.0001 |

| Religion | |||

| Orthodox | 4,355 | 1.00 | |

| Protestant | 1,975 | 0.61 (0.52-0.72) | <.0001 |

| Muslim | 4,374 | 0.66 (0.59-0.75) | <.0001 |

| Wealth index | |||

| Poorest | 2,882 | 1.00 | |

| Poor | 1,761 | 0.84 (0.64-1.09) | 0.185 |

| Middle | 1,637 | 0.79 (0.59-1.05) | 0.0996 |

| Rich | 1,663 | 1.51 (1.19-1.90) | 0.0006 |

| Richest | 2,953 | 8.29 (6.96-9.80) | <.0001 |

| Current working status | |||

| Not Working | 6,986 | 1.00 | |

| Working | 3,898 | 1.35 (1.21-1.51) | <.0001 |

| History of birth | |||

| 0-2 | 1,434 | 6.70 (5.42-8.31) | <.0001 |

| 3-4 | 2,409 | 2.68 (2.12-3.38) | <.0001 |

| 5-6 | 3,230 | 1.71 (1.32-2.22) | <.0001 |

| 7+ | 3,823 | 1.00 | |

| No of antenatal visits during pregnancy | |||

| 0 | 4,266 | 1.00 | |

| 1 | 338 | 2.01 (1.43-2.84) | <.0001 |

| 2 | 527 | 2.28 (1.73-3.00) | <.0001 |

| 3 | 901 | 4.83 (3.99-5.86) | <.0001 |

| 4+ | 1,705 | 13.45 (11.54-15.69) | <.0001 |

| Ever had child born dead | |||

| Yes | 154 | 1.00 | |

| No | 10,742 | 0.61 (0.41-0.91) | 0.0156 |

| Frequency of reading newspaper or magazine | |||

| Does not read | 9,621 | 1.00 | |

| Read once a week | 976 | 4.11 (3.54-4.77) | <.0001 |

| Read more than once a week | 287 | 5.94 (4.66-7.58) | <.0001 |

| Frequency of listening to radio | |||

| Does not Listen | 5,764 | 1.00 | |

| Listen once a week | 3,127 | 1.69 (1.48-1.93) | <.0001 |

| Listen more than once a week | 1,999 | 2.95 (2.57-3.38) | <.0001 |

| Frequency of watching television | |||

| Does not watch | 6,835 | 1.00 | |

| Watch once a week | 2,283 | 2.44 (2.11-2.83) | <.0001 |

| Watch more than once a week | 1,767 | 7.97 (6.97-9.12) | <.0001 |

Table 4. Unadjusted association of health facility birth in Ethiopia using logistic regression analysis.

Region, place of residence, mother’s educational status, husband/ partner’s educational status, ANC visits and exposure to media (newspaper, radio and television) were positively associated with selection of health facility as delivery place. The odds ratios of health facility births across region were smallest in SNNP (1.08) and highest in Addis Ababa (capital) (11.38) compared to women living in Afar region (the remote and hard to reach region in the country) and women living in urban area were 88% more likely to use health facility for delivery purpose (Table 4).

Higher level educated women and women married to higher level educated men had 11.52 OR (95% CI: 9.09-14.59) and 11.04 OR (95% CI: 9.03-13.49) to deliver at a health facility, respectively. Women who had less than or equal to two delivery experiences and had ANC visits more than or equal to four had 6.7 OR (5.42- 8.31) and 13.45 OR (11.54-15.69) to delivery at health facility, respectively. Not having child born death was negatively associated with health facility delivery. Women who had child born death experience were 61% more likely to utilize health facility delivery.

Health facility delivery utilization was strongly associated with media exposure. Women who read newspapers more than once in a week, listened to the radio more than once a week and watched television more than once a week were 5.94 (95% CI: 4.66-7.58), 2.95(95% CI: 2.57-3.38) and 7.97(95% CI: 6.97-9.12) times more likely to deliver their babies at a health facility respectively.

Adjusted Association of Each Variables with Health Facility Births

From a stepwise logistic regression using 15 variables, a total of 11 variables were allowed to enter the model at the significance level of 0.2 (Table 5).

| Variables | N | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | |||

| Afar | 944 | 1.00 | |

| Tigray | 1,173 | 1.15 (0.71-1.87) | 0.5748 |

| Ahmara | 1,415 | 2.29 (1.41-3.69) | 0.0008 |

| Oromia | 1,469 | 1.76 (1.12-2.78) | 0.0149 |

| Somali | 678 | 1.81 (1.09-2.98) | 0.021 |

| Benishangul Gumuz | 916 | 5.15 (3.26-8.12) | <.0001 |

| SNNP | 1,358 | 1.24 (0.74-2.06) | 0.4159 |

| Gambela | 832 | 4.11 (2.49-6.76) | <.0001 |

| Harari | 695 | 4.41 (2.76-7.05) | <.0001 |

| Addis Ababa(capital) | 746 | 4.99 (2.92-8.22) | <.0001 |

| Dire Dawa | 670 | 6.40 (4.04-10.16) | <.0001 |

| Type of residential place | |||

| Urban | 2,767 | 1.00 | |

| Rural | 8,129 | 0.24 (0.19-0.31) | <.0001 |

| Respondents’ highest educational level | |||

| No education | 7,166 | 1.00 | |

| Primary | 2,849 | 1.13 (0.92-1.38) | 0.244 |

| Secondary | 556 | 2.01 (1.33-3.05) | 0.001 |

| Higher level | 325 | 2.97 (1.58-5.60) | 0.0007 |

| Husband/partner's education level | |||

| No education | 5,407 | 1.00 | |

| Primary | 3,632 | 1.34 (1.09-1.64) | 0.244 |

| Secondary | 969 | 2.28 (1.69-3.07) | 0.001 |

| Higher level | 623 | 1.81 (1.23-2.65) | 0.0007 |

| Religion | |||

| Orthodox | 4,355 | 1.00 | |

| Protestant | 1,975 | 0.85 (0.64-1.14) | 0.2733 |

| Muslim | 4,374 | 0.69 (0.55-0.88) | 0.0024 |

| Wealth index | |||

| Poorest | 2,882 | 1.00 | |

| Poor | 1,761 | 0.87 (0.64-1.18) | 0.3708 |

| Middle | 1,637 | 0.75 (0.55-1.03) | 0.0738 |

| Rich | 1,663 | 0.97 (0.73-1.29) | 0.8343 |

| Richest | 2,953 | 1.54 (1.11-2.13) | 0.0096 |

| History of birth | |||

| 0-2 | 1,434 | 1.59 (1.21-2.08) | 0.0008 |

| 3-4 | 2,409 | 1.02 (0.77-1.35) | 0.9143 |

| 5-6 | 3,230 | 1.06 (0.78-1.45) | 0.6927 |

| 7+ | 3,823 | 1.00 | |

| No of antenatal visit during pregnancy | |||

| 0 | 4,266 | 1.00 | |

| 1 | 338 | 1.68 (1.12-2.49) | 0.0115 |

| 2 | 527 | 1.60 (1.16-2.22) | 0.0044 |

| 3 | 901 | 2.27 (1.78-2.91) | <.0001 |

| 4+ | 1,705 | 3.07 (2.48-3.81) | <.0001 |

| Ever had child born dead | |||

| Yes | 154 | 1.00 | |

| No | 10742 | 0.61 (0.32-1.19) | 0.1502 |

| Frequency of reading newspaper or magazine | |||

| Does not read | 9,621 | 1.00 | |

| Read once a week | 976 | 1.18 (0.88-1.59) | 0.27 |

| Read more than once a week | 287 | 1.78 (1.03-3.07) | 0.0381 |

| Frequency of watching television | |||

| Does Not watch | 6,835 | 1.00 | |

| Watch once a week | 2,283 | 1.32 (1.07-1.63) | 0.009 |

| Watch more than once a week | 1,767 | 2.01 (1.54-2.62) | <.0001 |

Table 5. Adjusted association of health facility birth in Ethiopia using logistic regression analysis.

After adjusting for potential confounding variables, region had a significant association with health facility delivery. Compared to women who lived in Afar region (the remote and hard to reach area in the country), women who lived in Addis Ababa (capital) and Dire Dawa (the second city administration in the country) had 4.99 OR (95% CI, 2.92-8.22; p<.0001) and 6.40 OR (95% CI, 4.04-10.16; p<.0001) to give birth in a health facility respectively. Women who lived in rural areas were 76% less likely to deliver at a health facility with 0.24 OR (95% CI, 0.19-0.31; p<0001). Religion had a significant association with the selection of delivery location. Muslim followers were 31% less likely to deliver at a health facility compared to Orthodox follower.

From this data analysis, after adjusting all variables for respondents educational level, women who have higher level education were 2.97 (95% CI, 1.58-5.6; p=0.0007) times more likely to deliver at a health facility. Husband/partner’s educational level also had a significant association after adjusting all variables. Women married to secondary level educated men were 2.28 (95% CI, 1.69-3.07; p=<.0001) times more likely to deliver at health facility. In third world countries, Wealth Index plays a role to choose the place of delivery. Compared to the poorest women, the richest women were 1.54 (95% CI, 1.11-2.13; p=0.0096) times more likely to give birth at a health facility after adjusting all variables.

History of parity was negatively associated with health facility delivery. After adjusting all variables, women who had two or fewer delivery experiences were 1.59 (95% CI, 1.21-2.08; p=0.008) times more likely to give birth at a health facility. Antenatal care visits had a positive association with health facility births. Women who had greater than or equal to four ANC visits had 3.07 OR (95% CI, 2.48-3.81; p<.0001) to give birth at a health facility and having child born death had no significant association with delivery places after adjusting for all confounding variables (Table 5).

Furthermore the study revealed that after adjusting all variables in the model for newspaper reading and watching television, women who read newspapers and watched television more than once a week had 1.78 OR (95% CI, 1.03-3.07; p=0.0381) and 2.01 OR (95% CI, 1.54-2.62; p<0.0001) to give birth at a health facility respectively. However, variables like women’s age, marital status, women’s working status and frequency of listing radio had no significant association with selection of delivery place after adjusting all corresponding variables.

Maternal mortality is still very high in developing countries and health facility delivery very low. Only 13.5% (1,467) women gave birth at a health facility which was slightly greater than results from the Demographic and Health Survey final report (Central Statistical Agency 2011). This is one of the reasons many Ethiopian women die due to pregnancy and pregnancy related causes. Even though health care facilities are not fully covered nationwide, health facility delivery reduces maternal mortality chances. Women’s age was negatively associated with health facility utilization for delivery purpose. This study also showed that younger women tended to give birth at health facilities than older women and were 13.30 times (OR (95% CI) = 13.30, (7.63-23.18)) more likely to give birth at health facilities. While the youngest women are starting to use health facilities as delivery place, health facility delivery coverage is still very low nationwide (10%). The generational changes in younger mothers intending to give birth in facilities provide reassurance and hope to reducing maternal mortality rates and achieving the Millennium Development Goal in some developing countries; however some developing countries including Ethiopia show slow progress to achieve the MDGs [7].

Normally we expect women who are married to have good care and support from their husband/partner in financial and other social aspects. However, this study reveals that marital status of the women was negatively associated with health facility births. Married women were 63% less likely to give birth at a health facility. From this finding we understood that Ethiopia is a male dominated country and some sociocultural attitudes have not changed yet. A similarly conducted study in Bangladesh and Burkina Faso show that male dominance increases first delay referral to make a decision for health facility delivery [20]. Non-married women can use health facilities for delivery purposes and decide by themselves where they want to give birth and expense money for their health and outcome of pregnancy.

Health facility births have significant variation among the different region in the country and its OR ranges from 1.08 in south nation nationality people (SNNP) (95% CI, 0.75-1.55; p=0.6726) to 11.38 Addis Ababa (capital) (95% CI, 8.28-15.64; p<.0001) to use health facilities as a birth place compared to women living in Afar region. From the finding we believe that health facility and health professional distribution are not equal and health education and awareness on health facility delivery are relatively different across the region in the country. Due to concentration of health facilities and health professionals in urban areas, most women living in urban areas were 88% more likely to use health facility as their birth place compared to women living in a rural part of the country [21].

Education plays a great role in human daily life. Its value ranges from daily human activity to worldwide technology development. The majorities of Ethiopian women are not educated and have no economic empowerment to decide where they want to deliver babies. Due to their sociocultural background most of the decisions are made by their husbands and elders in the home [5,17]. In this study women who had higher levels of education and were married to more educated men had 2.97 OR (95% CI, 1.58-5.6; p=0.0007) and 1.81 OR (95% CI, 1.23-2.65; p=0.0024) to use health facility as delivery place respectively. A similarly conducted study in Nepal and India indicated that educational level, frequency of ANC visits and distance from health facility has a significant association with health facility delivery [21,22]. Developing countries have different constraints that influence women’s health facility births. Economical affordability, health facility access, and shortage of qualified health professionals are some of the constraints [23]. This study verified that, compared to the poorest women, the richest women were 54% (95% CI, 1.11-2.13; p=0.0096) more likely to give birth at a health facility.

As parity increases, spontaneous vaginal births are easier than nulliparous mother; howeve, there is more risk of developing pregnancy related complication during labor and delivery [24,25]. Number of parity was negatively associated with health facility delivery. Compared to women who had four or more delivery experiences, women with two or fewer delivery experiences were 59% (95% CI, 1.21-2.08; p=0.0008) more likely to give birth at a health facility. We believe that younger women had more concession about their pregnancy and babies due to the expansion of education and media relatively increasing during the past one to two decades in the country. Women who have ANC visit experiences are mostly delivering at a health facility. This shows that advice and education they received from health professional during ANC visits influence them. Women who had ANC visits four or more times had 3.07 OR (95% CI, 2.48-3.81; p<.0001) to give birth at health facility which was similar with other studies [22,23]. Interestingly, child born death experience had no association with delivery places. This indicates that birth location has no impact on child survival according to this study result in Ethiopia. Normally, we expect that children born in health facility had a higher survival chance than those born at home. Children survival depends on skill of health professional who attends the deliveries. This is one of the indicators for low health facility delivery coverage in the country; there is no difference between home delivery and health facility delivery for child survival according to our study result.

In human life, media plays a great role in daily life and has great impact on improvement of socio-economic conditions of the country. Women live in developing countries do not have access to media to exchange ideas and information with each other for their daily life improvement. Newspaper, radio and television have great roles on health promotion and education and sharing new idea and information. In Ethiopia the coverage and access of this media are low. Women who live in the rural part of the countries have no access for those media. This study shows that compared to women who do not read newspapers and watch television, women who read newspapers more than once in a week and watch television more than once in a week had 1.87 OR (95% CI, 1.03-3.07;p=0.0381) and 2.01 OR (95% CI,1.54-2.62;p=<.0001) to deliver at a health facility respectively. A similarly study conducted in India shows that women who had media exposure are more likely to delivery at a health facility [26-29].

This study is the first national study that examined the factors associated with health facility delivery by using a large-scaled national survey data in Ethiopia. It investigated demographicrelated factors, pregnancy-related factors and media-related factors which were significantly associated with delivery place selection in Ethiopia. We believe that it can help country health policy makers during their planning of health professional development in the region and construction of health facilities (health center, hospital and others) according to their population size in different region in the country.

Through detailed analysis, we were able to consider many factors such as region, type of residential place, religious, educational level, working status, number of ANC visits, number of parties, children live status and media exposures (reading newspaper, listen to radio and watch television) that were statistically significantly associated with health facility delivery in Ethiopia [30,31].

Despite the strength of this study being a nationwide survey data, it has a limitation of being a cross-sectional study. It can provide only statistical evidence of those variables with delivery place choice and cannot show a causal effect.

This study verifies that in Ethiopia utilization of health facility as delivery place across regions and place of residence have significant differences. This indicates there was difference in health facility and health professional distribution, awareness on health facility delivery, health education and promotion across region. Policy makers, non-governmental organizations, and other partners can consider this issue during planning and development of health sector program. Women education and husband/partner involvement in decision making have significant role in selection of delivery place. Special consideration is needed to educate and empower women for maternal mortality reduction in the country. Another interesting finding in this study was children live statuses have no association with delivery place. Special consideration on health facility birth and health professional skill improvement will be needed in the future. Women’s media exposure had significant association with health facility delivery. Health promotion and education through media have great role in improvement of health facility delivery promotion. So it indicates that media expansion and access for media have great impact on maternal mortality reduction in the country.

Further studies will be needed to address why women in Ethiopia do not like to deliver at health facilities in the aspect of sociocultural in qualitative method to come up with evidences of those factors and evade health facility utilization for delivery purpose in the country. Similarly we recommend study focusing on health service quality in delivery area and Ethiopian health professionals’ behavioral and psychosocial support for pregnant mother during labor and delivery.

Citation: Setu NL (2021) Who Gives Birth at Health Facility in Ethiopia? Result from Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2011. J Women's Health Care 10:550. doi: 10.35248/2167-0420.21.10.550.

Received: 01-Sep-2021 Accepted: 15-Sep-2021 Published: 22-Sep-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2167-0420.21.10.550

Copyright: © 2021 Setu NL. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.